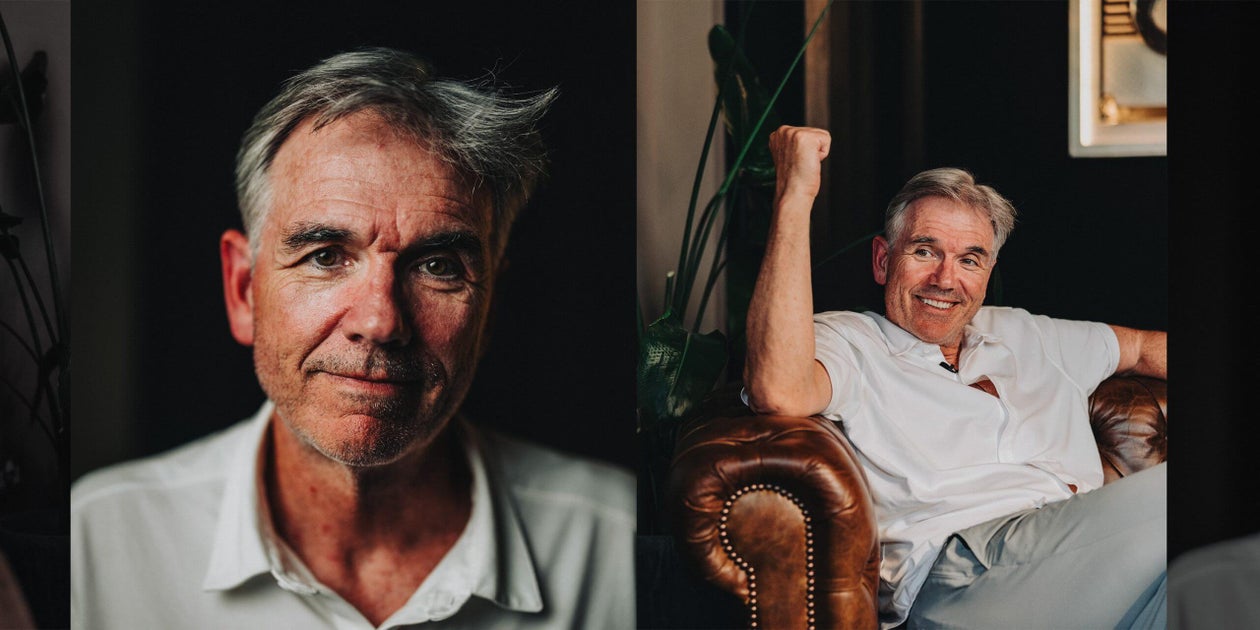

It’s pretty hard to stay grounded when a major film is made about your life, harder still when a two-time winner of the Sexiest Man Alive award is cast to play you.

But Billy Beane shows no signs of letting Brad Pitt and Moneyball go to his head. He carries himself with a relaxed humility, freely admitting that “my success has been driven by having really smart people around me”.

He’s joined in Belfast by one of those smart people: Luke Bornn, a scientific adviser for Teamworks and former Harvard statistics professor whose career spans Italian football side Roma, the NBA team Sacramento Kings, and a French football club, Toulouse FC, where he oversaw a data-driven rebuild.

When The Athletic spoke to the pair, they were eagerly awaiting The Open Championship at Royal Portrush, golf’s fourth and final major of 2025. But before soaking up Scottie Scheffler’s masterclass, they sat down for an hour for a wide-ranging conversation that touched on:

The seismic impact of Moneyball

Why football has struggled to follow baseball’s analytical revolution

The evolving role of the manager and Beane’s admiration for Sir Alex Ferguson

How data identified Mohamed Salah early

The strengths and perils of singing younger players

Why data has had “little to no impact” on tactics

With data now deeply embedded across modern sport, it’s easy to forget just how radical Billy Beane’s approach was as general manager at the Oakland Athletics. A former player, not a number-cruncher, he wasn’t the obvious figurehead for sport’s analytics revolution.

But it was precisely that background that gave his evidence-based approach credibility in a world still dominated by ex-pros. “When we were implementing data and doing things differently, they weren’t able to say, ‘Well, what do you know, you haven’t played’,” Beane said.

At the turn of the millennium, with Beane as general manager, the Oakland Athletics reached the playoffs in four consecutive years, and in 2002 became the first team in more than 100 years of American League baseball to win 20 games in a row.

Beane, now a senior adviser and minority owner at the Athletics, sees himself as the “Trojan horse” who smuggled more technically minded thinkers like Bornn through the boardroom gates.

In baseball, the cloak-and-dagger approach is no longer necessary, where data scientists now move freely through the corridors of power and are a vital part of top-level decision-making. Beane jokes that he “wouldn’t be able to apply for a job now because I’m not qualified” and says that he’s competing with top-tier companies such as Google, Goldman Sachs, and JP Morgan for data talent.

Bornn, a former co-founder of Zelus Analytics, says that the same shift in football is lagging further behind, with former players still clutching the reins tightly. “I think it is evolving, but much slower than public perception would have you believe.”

Beane’s success ushered in a top-down approach across sport, where data-hungry executives rather than managers hold sway. But for Beane, it was never about marginalising the coach, rather “redefining” their role.

“What we tried to do at Oakland,” he explains, “is we wanted the manager to manage the team, manage what was going on here in the game, and then give him the tools to be better at that. But to expect him to see every other game that’s going on in the rest of the league, that’s an impossible task.

“And quite frankly, what data has allowed you to do in some respect — not just in baseball, but in every sport — is it allows you to evaluate every game and everything that’s going on without having to see it.”

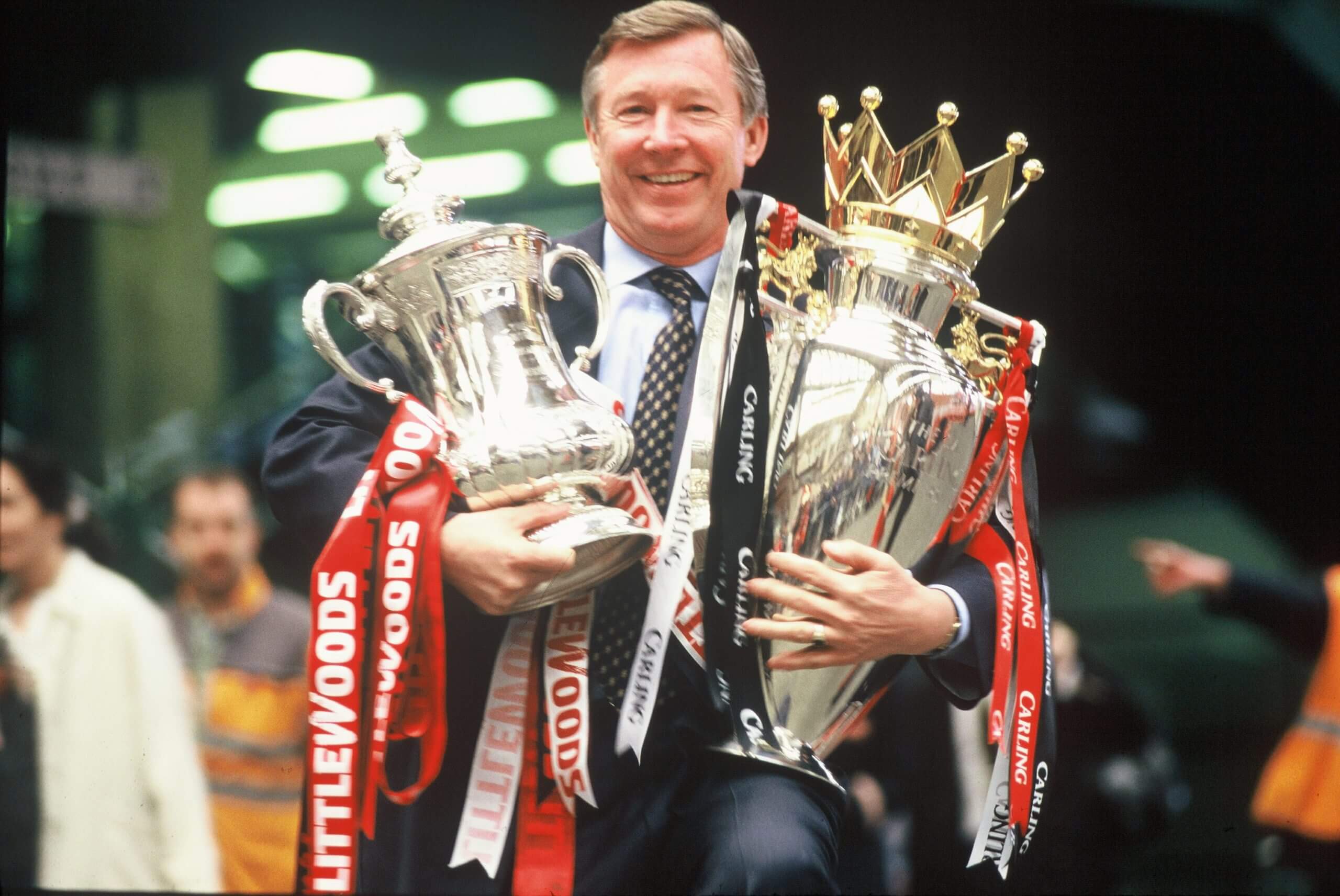

He has a special admiration for the way Sir Alex Ferguson ran Manchester United, a club where he spent 26 years as manager and won 38 major trophies.

“Most of them (managers) move on to bigger, better jobs and better compensation, but there are a few icons in each sport.

“And one reason I think they’re great — whether it be Sir Alex Ferguson, Bill Belichick (six Super Bowls with the New England Patriots during a 24-year spell), Nick Saban in Alabama (six national championships across a 16-year tenure) — is because they ran their club like they’re never going to leave, which is unusual, and the decisions they make are for the future.”

Ferguson holding the FA Cup and Premiership trophies after completing the Double with United in 1997 (John Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

He likens Ferguson’s long-term view to how Fenway Sports Group run Liverpool, led by Beane’s personal friends John W Henry and Tom Werner.

“They have resources, but they also deploy capital wisely and efficiently,” he says, later pointing to how they reinvested the £142million ($190.5m) received from Barcelona for Philippe Coutinho in January 2018 to build a title-winning team.

But Beane recognises the challenge of thinking along these long-term lines amid the constant pressure from fans to “win now”.

“We all want to run our sports teams like Warren Buffett runs his Berkshire Hathaway. It’s not always easy to do that… what separates clubs is their ability to execute and sort of fend off the noise.”

Since Ferguson’s departure, United have struggled to maintain this sustained vision, instead cycling through managers with varying tactical visions. Bornn warns against this.

“If there’s an evolution every six months, 12 months, 18 months, and every coach wants to do things slightly differently, wants a different type of player, that leads to a tremendous amount of inefficiency from the recruitment perspective.”

Both highlight the pitfalls of narrowly focusing on certain targets or positions in the transfer market. Beane argues that instead of reactively filling a weakness, teams should look at where the best value lies.

“Teams will say we need a left-back, so you just look at the left-backs… but maybe the better value is in strengthening a strength.

“Running a sports team is ultimately about maximising the dollars that you have in being efficient. And I think you get myopic sometimes — when you have a need, you look specifically for people who can fill that weakness as opposed to maybe getting better value and making a strength even stronger.”

Whereas data analysis in baseball has evolved to the point where every “baseball team has a pretty good idea how good a player is right now”, it still gives a major edge to those who use it in football. Structural differences between the sports play a part.

“Baseball is very closed. The one thing about football is it’s a world game. You’ve got different leagues, different cultures. In baseball, we have no relegation and just 30 teams. Systems that are successful are quickly adopted.”

Conor O’Neill speaking to Billy Beane and Luke Bornn (TeamWorks)

Bornn is more sceptical about the cultural side of football’s slow uptake.

“We’re going to look back in 10 years and laugh at it. Because we’re the spot where a lot of teams hire data analytics folks because they don’t want to look like Luddites.

And they say publicly, ‘Yeah, we are data driven’, but yet internally they don’t actually use it. They don’t want to look like they’re old-fashioned, so they hire the people and put that public image out there, but then internally make the decisions traditionally.”

Beane agrees that this data window-dressing exists, but points to Brentford and Brighton as clubs that, in his view, “use data for all their decisions, not just now and again when it backs up their opinion”.

“The data’s out there for everyone, information’s out there for everyone. Really, executing on that data is the most important thing. And some teams do it better than others.”

With data uptake still patchy across football, there’s a clear edge for those who know how to use it properly. Beane explains that the top names flagged by the models typically align with who we instinctively consider the world’s best and that advanced models often incorporate the “wisdom of the crowd” when scanning for talent.

The real opportunity, he says, lies in spotting the lesser-known outliers hidden among the elite.

“What you want to do is when you see Lionel Messi, you see all the usual suspects up there, and then all of a sudden some kid named Jude Bellingham pops up as a 17-year-old playing at Birmingham, you realise, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s a 17-year old kid who’s playing at a level as one of the top 15 players’.”

Bellingham playing for Birmingham in 2019 (Nathan Stirk/Getty Images)

He later references Viktor Gyokeres’ spell at Coventry as another hidden gem who was playing in the Championship, English football’s second tier. Gyokeres has recently joined Arsenal from Sporting CP in a move worth an initial €63.5million (£54.8m; $74.2m) plus €10m in add-ons.

“That’s where it’s at, when you sort of find those guys the year before they go to that top four or five club. When Luis Suarez came over from Uruguay, he was playing in the Dutch league, right? That’s a great example. I’m pretty sure data was part of that decision-making process. And he turned into one of the best players in the world.”

This idea of using data to spot value early ties into football’s modern obsession with youth. “The reason that young players were valuable to the Oakland A’s wasn’t because they’re young, it was because they were cheap,” said Beane, adding that this approach drives profitable player trading because “you’ve got economic value at the end of the contract, too”.

The Chelsea co-owner and chairman Todd Boehly has closely followed Oakland’s blueprint, pouring considerable resources into young talent. Boehly also owns 20 per cent of the Los Angeles Dodgers, a team Beane holds in the highest regard.

“The Los Angeles Dodgers, to me, are really sort of the pinnacle of how sports teams should be run, particularly ones that have a lot of capital. I mean, not only do they have a lot of money, but they’re brilliant.

“They have brilliant staff. They’re efficient. They’re ruthless in their implementation of what they believe in. You can make the argument that they’re the most valuable sports team in the entire world. And the most efficient and the most successful… I have a lot of respect for what they do there.”

The Dodgers have won two of the past five World Series titles, including the latest in 2024, spearheaded by the remarkable Shohei Ohtani.

Ohtani signed a 10-year $700million contract with the Dodgers in 2024 (Alex Slitz/Getty Images)

But Bornn thinks that, in football, the youth-recruitment pendulum may have swung too far. “You look at what they’re spending on these players and think, is that the right choice?” he says. To only “recruit players under 22 or under 24 would be ridiculous because you want to get the best value you can, whether that’s a 35-year-old or an 18-year-old”.

And Bornn knows a thing or two about spotting value.

During his time at Roma, he was involved in the recruitment of Mohamed Salah, Antonio Rudiger and Alisson. On Salah, in particular, he’s unequivocal. “At the time, our models said he was one of the best players in the world. It’s like when I was at the Sacramento Kings when Luka Doncic was drafted and people said, ‘Oh did your models like Doncic?’ And I was like, ‘Anyone who looked at data for 10 seconds would have loved Doncic.’

Salah moved to Liverpool for around £37million in 2017 and will go down as one of the club’s greatest-ever players. He is their third-highest goalscorer of all time and has played pivotal roles in two Premier League title wins, a Champions League triumph, and reaching the final on two other occasions.

But while Bornn has used data to unearth elite talent, he still considers football analytics relatively rudimentary.

By modern standards, the use of statistics in Moneyball is also basic, focused largely on identifying undervalued players using metrics such as on-base percentage. Today, they use advanced machine learning models to paint a more complete picture of player performance. Beane believes that baseball has “significantly explored using AI for making player selections and player evaluations”.

Football, Bornn says, is “still kind of back in the on-base percentage days… but it’s growing very rapidly”. The advent of off-ball tracking data, in particular, has added a new layer of insight, allowing analysts to measure things like the value created by off-ball runs.

“It used to be like, ‘This player’s good because they have a lot of success dribbling or a lot of take-ons’. So basic counting stats. And now we can say things like, ‘This player is great because he makes these off-ball runs which open up space for passing lanes which increase the expected value because it opens up this passing or this through a ball’.”

But the sport still lags in assessing technical skill: “In soccer, we’re not quite measuring yet the quality of the first touch or the exact execution of the pass in terms of the projection of the ball.”

In comparison, Bornn sees baseball as a leader when it comes to pinning down the biomechanics that make the sport tick.

“Baseball is ahead of other sports in multiple areas. Biomechanics is definitely one of them. There are actually good reasons for that,” Bornn explains.

“Pitching mechanics — because they’re sort of on the mound and in one spot — are much easier to analyse than, let’s say, a striker’s shot, because of the movement, because of the distance of the cameras, all that kind of stuff.

“But they’re doing things now where they will have guys, you know, ‘Hey, if on your release, you get your elbow like a little bit more this way, we can deliver this many newton meters of force on the ball’. It’s just incredible what they’re able to do and, like, add meaningful velocity, meaningful spin to pitchers.”

Edwin Diaz pitching for the New York Mets earlier this month (Al Bello/Getty Images)

This forensic breakdown of player mechanics matters because it separates repeatable processes — like good passing technique or ball-striking in football, which translates across levels — from results-based metrics like goals and assists, which are more dependent on context.

For Beane, process is paramount. “People used to pay for goals, but then they saw expected goals (xG) have more of a process.” Bornn adds to this: “With expected goals, you’re just removing some randomness, and by removing that randomness, you’re essentially better at predicting the future.”

Despite breakthroughs, analytics has yet to make a meaningful impact on how the game is played. Bornn says, “The overall impact on tactics has been little to none.”

“I think there’s still a pretty big cultural gap. There are definitely isolated examples, especially for specific examples where the data is really clear, like certain set-piece tactics, where there’s no question that data has changed certain teams the way they do set pieces.

“In fact, even us at Toulouse, the year that we got promoted, we had just incredible set-piece numbers. Brentford, Midtjylland are known for this.”

Bornn is no longer involved with Toulouse but a year ago Zelus Analytics was acquired by Teamworks, for whom Beane is an investor. Teamworks is an operating system used by thousands of professional and collegiate sports teams across the globe, including all 32 NFL teams and 90 per cent of Premier League clubs.

Bornn has an advisory role for their data analytics arm, Teamworks Intelligence, which provides teams with their own data platform to use in their day-to-day operations.

Beane lightly ribs Bornn during the hour-long conversation, flashing a mischievous, knowing grin as he asks: “But how do you measure heart, Luke?”

Later, he jokes: “You’re basically trying to take all the romance out of sports, aren’t you? Oh yeah, come on. You really are. You really turned it into a math class, and none of us like math.”

Yet despite the teasing, the lasting legacy of Moneyball for Beane is that it has empowered brilliant minds such as Bornn’s to get involved in running sports teams.

“To me, that’s been the best thing about the data revolutions: all the brilliant people that are now a part of it,” he says. “You think of all the young kids growing up who didn’t play Major League Baseball, which basically represents 99.9 per cent of the population who didn’t play in the big leagues, but are Yankees fans or Dodgers fans. And they went to MIT and they now get a chance to work for the Dodgers or the Yankees.

“And think about football, they now get to work for Chelsea or Man United, or Liverpool. They’ve got mathematics degrees from university — 20 years ago, people wouldn’t even turn their resume.

“These are brilliant young men and women who now have the opportunity to work. To me, that’s the beauty of the data revolution is that the best and the brightest now get the opportunity to work in an industry that they’re passionate about.”

(Top photos: TeamWorks)