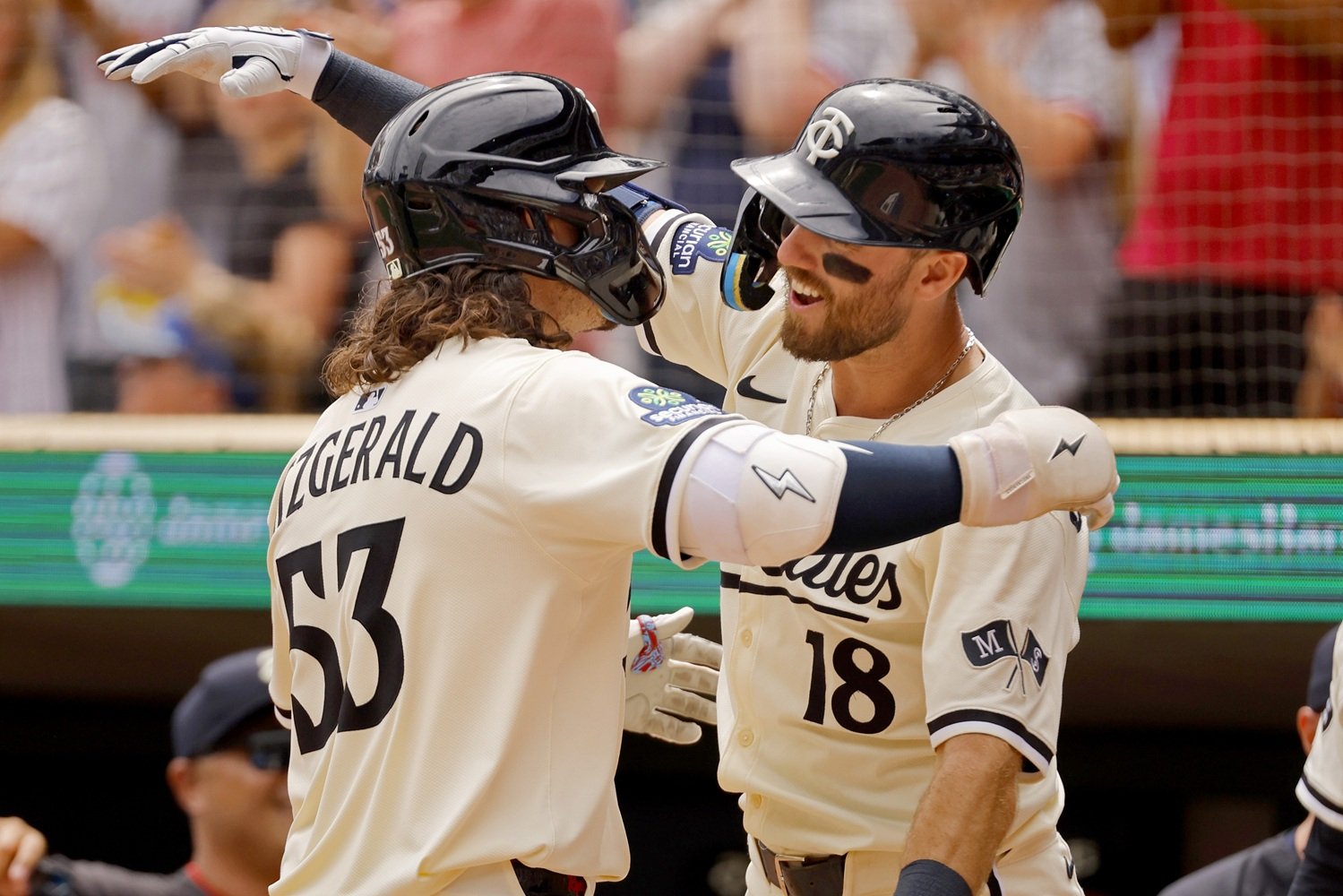

Ryan Fitzgerald is 31 years old and has appeared in nine MLB games. He’s likely not in the Twins’ plans beyond the 2025 campaign, and his days in professional baseball may be numbered. That’s just the reality for a player of Fitzgerald’s ilk. But one doesn’t amass over 400 games at the Triple-A level without having talent or the desire to improve. For Fitzgerald, this desire came to the fore during the 2020 COVID-cancelled minor-league season.

“In 2019, I had the highest line-drive percentage of the Statcast Era. I think the next-highest was like Freddie Freeman’s, around 31%. I think I was half a percent higher or something like that. So I was trying to figure out, ‘Ok, I’ve got a below-.700 OPS but I’ve got a really high line-drive rate. What’s going on here?’” said Fitzgerald, who was in the Boston Red Sox organization at the time. “I was like, ‘I’ve gotta add bat speed.’”

Bat speed has become one of the hot buzzwords in the baseball lexicon over the last few seasons, due largely to MLB publishing swing data for every MLB player on their hyper-specialized stats site Baseball Savant. However, teams have been tracking bat speed and other swing metrics for quite some time.

“I think my average bat speed in games in 2019 was like 68 and change [miles per hour]. Obviously, league average is 71.3, somewhere around there. So going into 2020, I got with a guy named Ryan Johansen, who was at the time one of the hitting coordinators for the [Chicago White Sox]. I was working with him pretty much that whole offseason—all of 2020. Just trying to figure out how I can increase bat speed.”

Fitzgerald’s swing speed in limited MLB action? 71.3 mph.

Nnk5QVlfV0ZRVkV3dEdEUT09X0JnUUFBQVVEQlFjQURsb0NVUUFIVkFOWEFGa0ZCVkFBQlFRQ0FBSU1DVkZVQWdwVQ==.mp4

Swing metrics are one of the many aspects of baseball that successfully marries concepts of physics to the sport. As the sport is largely rotational—one can’t throw a ball or swing a bat without rotating, after all—all of the forces generated by the athletes are technically torques, the rotational equivalent of linear force.

However, linear force (F) is familiar and easy enough to understand, so it is often used to explain the benefits of increased bat speed. As Isaac Newton described over 300 years ago, force is equal to the mass (m) of an object multiplied by its acceleration (a); the famous F=ma. Acceleration can further be described as the change of velocity (v) over time (t), morphing the equation to F=m(v/t). So, at its most basic level, force production is directly related to velocity—or in the case of Fitzgerald, swing speed.

“[Johansen] put me on a bunch of different programs and kind of got me right,” Fitzgerald said. “I went and got a bat-fitting done, changed my bat. That helped a lot. I was swinging a really small and light bat. I went to a bit longer bat, and slightly heavier; a different model.”

By increasing the weight (literally the mass) of his bat, Fitzgerald improved both variables that contribute to force production, m and v/t. The result was a career minor-league OPS of .770, though outside of a poor .704 mark in 127 games in 2022, his numbers regularly landed north of .800. That kept his career viable long enough to eventually bring him all the way to the place players dream of reaching—the majors.

But how, exactly, did Fitzgerald go about improving his bat speed? A mix of weight training and bat speed work.

“I linked up with a trainer after the 2021 season named Bill Miller, and he got me on a ton more weight room-specific bat speed stuff,” Fitzgerald said. “Ryan Johansen helped me more with my swing and stuff like that in the cage, but then I was able to couple that with Bill’s training. A lot of isometrics. A lot of fast-twitch movements. I mean, we measure pretty much everything I do in the weight room there, so that’s been huge for me.”

Measuring force and power output on a regular basis is standard practice at all levels of professional baseball (and increasingly, college and high-school ball, as well). The primary tools used to gather such metrics are force plates. These sensors, which can be embedded under a batter’s box or used as isolated above-ground units, can measure force and power data to ridiculously precise degrees. This allows teams to determine an athlete’s strength and power, and develop appropriate training protocols. One metric commonly used by teams is the Dynamic Strength Index, which is determined by finding the relationship between the athlete’s maximal force production during an isometric pull (strength) and a jumping task (power). If the athlete can produce a lot of force but not very quickly, they’d benefit from power training, which emphasizes moving weight quickly. If they can produce force quickly but not very much, they’d benefit from strength training, which is all about producing as much force as possible.

For Fitzgerald, he needed to improve his power.

“I’ve always said, squatting more weight in the weight room isn’t really gonna help you on the baseball field. If you can get to a certain threshold, I think that’s plenty of strength that you’re gonna need. Developing those Type 2 muscle fibers and those fast-twitch muscles are really what you want to do,” Fitzgerald said. “I’m not concerned about squatting 400 pounds in the weight room; I’d rather move 225 extremely fast. I think that’s gonna play better, in terms of bat speed, athleticism, pretty much everything you need on a baseball field.”

(Writer’s note for clarification: Type 2 muscle fibers are often referred to as fast-twitch because, among other things, they contract more quickly than their Type 1 counterparts.)

However, not all athletes would benefit from the same approach as Fitzgerald. In fact, it’s possible that he would have seen similar results from squatting 400 pounds. Again, consider the equation F=m(v/t). This formula stipulates that there are three viable ways to increase force production: 1. Increasing m (i.e., squatting 400); 2. Increasing v/t (i.e., moving 225 really fast); or 3. Doing both.

The key to developing individual athletes is working together with them to determine their preferred method of training and developing training programs to improve their weaknesses. Johansen and Miller did that expertly with Fitzgerald, and it paid off.

Matthew Trueblood contributed reporting to this story.