In a completely objective view, Carson Kelly is having a fine offensive season. It’s the best of his career, in fact. Kelly carries a .255/.344/.455 line, a 17.9% strikeout rate, an 11.5% strikeout rate, and a 125 wRC+ across the stat sheet. Those marks stand as the best of his career, save for a 2019 on-base percentage that was slightly higher and a couple of years with a touch higher walk rate.

Among the 21 backstops with at least 350 plate appearances to their name, Kelly sits fourth in wRC+ and in the top 5-7 just about everywhere else that isn’t batting average. So not only has he been excellent by his own standards, he’s been elite by the standard set by the position’s production in the broader context of the league. Sure, some of it’s carried by his scorching start to the year (a 257 wRC+ through the end of April), but even since the start of May, his OPS is a very respectable .694.

There is, however, also an interesting trend starting to develop in his game as we reach the final stretch.

Since August 25—a somewhat arbitrary date, but it gives a decent-enough sample in going back to Kelly’s last 38 plate appearances—Kelly is hitting only .206, while striking out almost 27 percent of the time. What he is doing, though, is hitting for power. Over that same stretch, Kelly’s ISO sits at .353, and he’s hit four home runs. The latter figure is tied for the team lead while the former sits nearly 50 points ahead of the Cubs’ second-place hitter in that timeframe (Ian Happ, at .309). All of these are classic hallmarks of a guy selling out for power.

The concept of “selling out” in order to get the ball to travel may or may not serve as a bit of an oversimplification here. We’ll circle back to those. But there are a number of trends that would indicate damage is what’s on Kelly’s mind each time he steps to the plate.

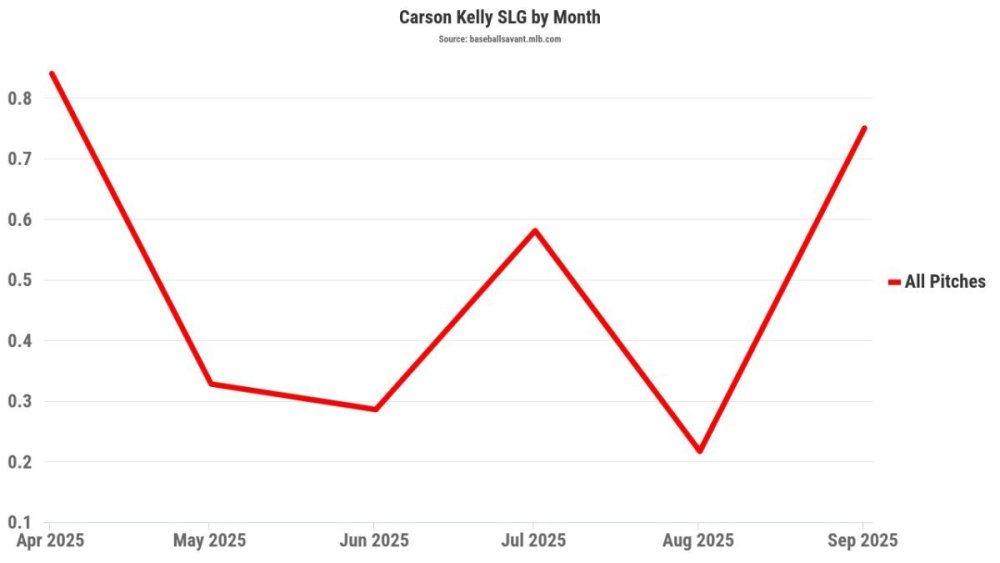

The first thing worth noting is just the general trend of slug:

Kelly’s production on the slug slide has been on the visible upswing so far in September, accounting for 26 of those 38 PA we’re discussing. Case in point: four of his six overall hits in September have found their way into the seats. That’s hardly surprising, though, when you consider what the bat’s doing.

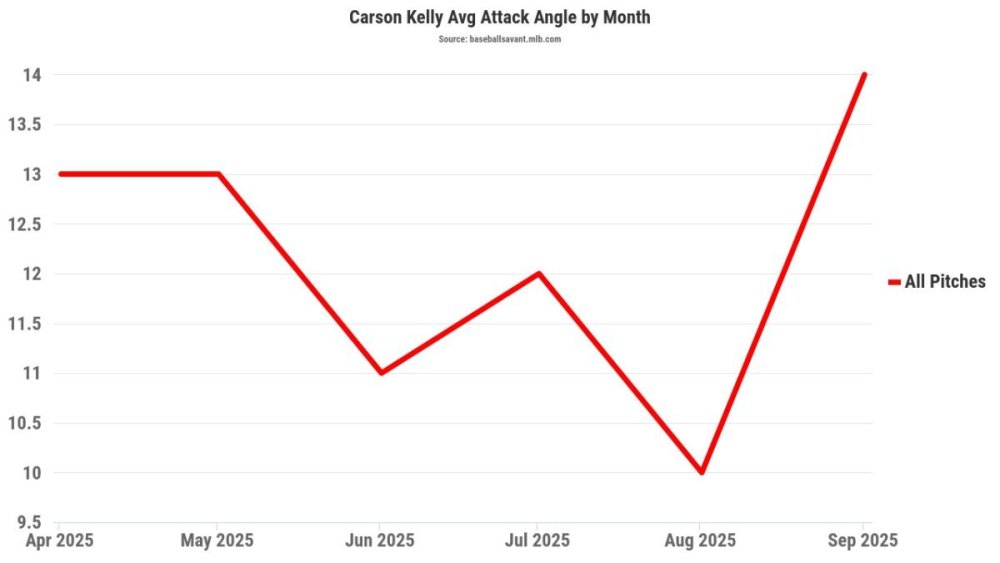

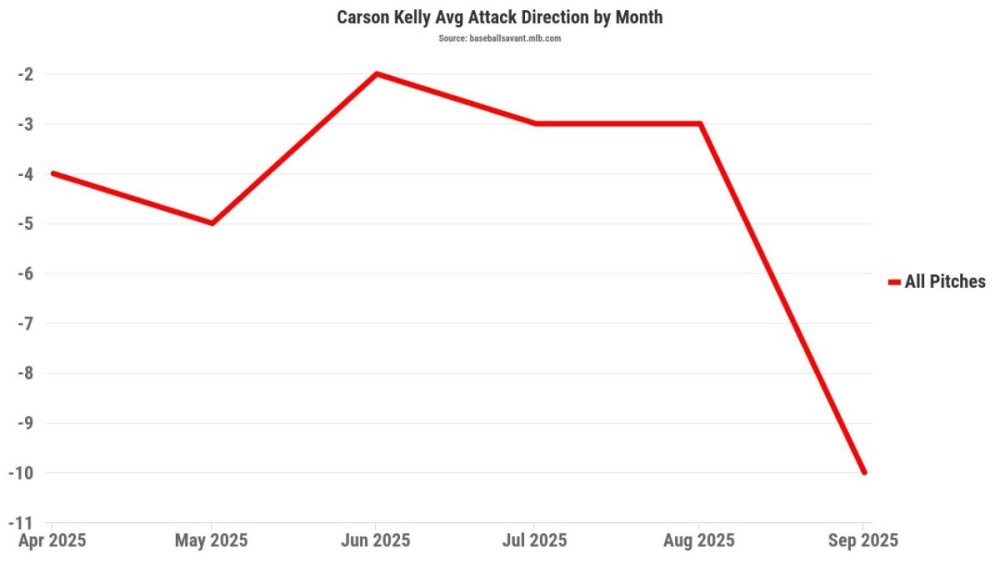

Attack angle is a new metric on the scene. For the uninitiated, it refers to the angle at which the barrel of the bat is traveling (relative to the ground) at the moment of contact. This is Kelly’s throughout 2025:

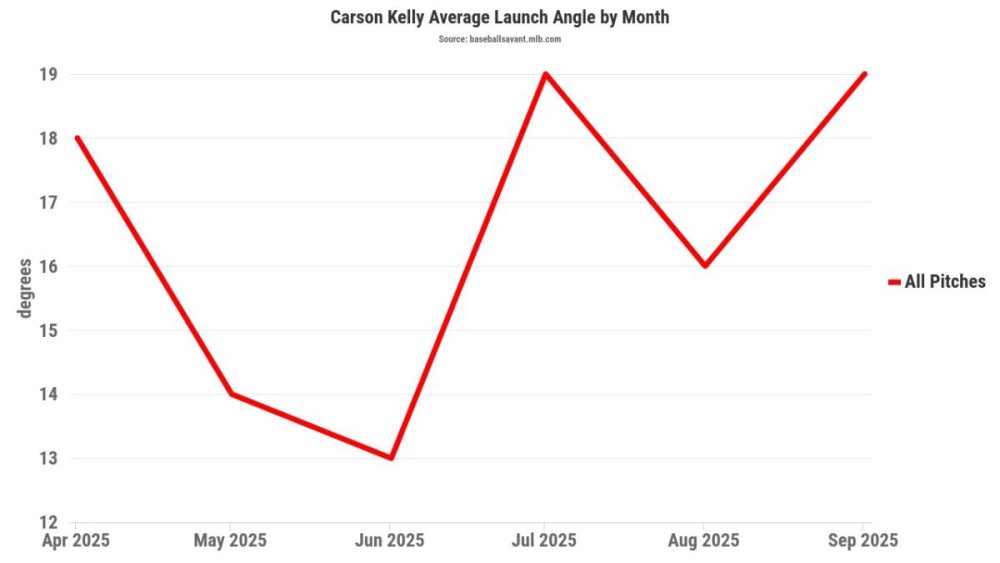

Kelly’s attack angle is at 14° in September, easily the steepest angle with which he’s worked this year. Steeper attack angle often begets a steeper launch angle, so it’s probably not going to come as any sort of surprise that Kelly’s launch angle looks like it does right now:

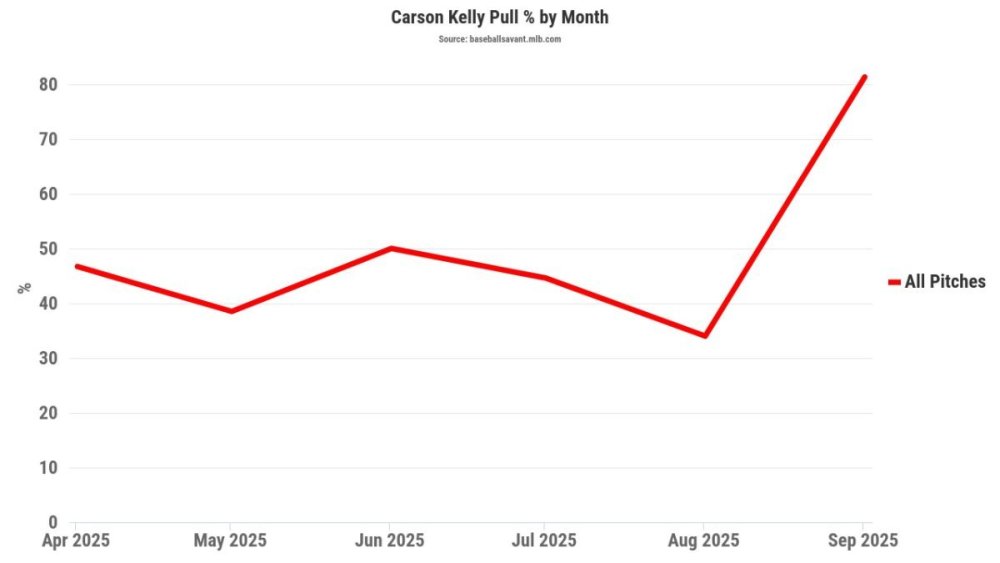

Factor in the pull rate:

And you have a very clear trend beginning to emerge. Attack angle is a timing metric, essentially; it tells us how much the hitter has gotten his bat working up through the hitting zone by the time they reach the contact point. Every swing starts downhill, as the barrel sweeps behind a batter and heads for a place in front of them. Knowing a player’s attack angle (especially in the context of that player’s usual number) tells us how long the barrel has been rising by the time the ball arrives. It pairs with another metric, attack direction, which gives the angle of travel of the barrel relative to the playing field, instead of to the diamond. Kelly’s attack direction has also moved significantly, and here, the trend is a bit cleaner and more sudden.

A negative attack direction is one oriented to the hitter’s pull field, so this is telling us that Kelly has moved dramatically toward getting around the ball more. This isn’t the same as his pull rate, which we looked at above, but they’re closely related, of course. He’s getting to the ball with his bat both going up more steeply and around the ball a bit more. As you’d guess, that means he’s catching the ball farther out in front of his body. As you might not guess, but will learn to, this also means his swing is a bit flatter, in one sense.

Wait. We just said he’s steeper. You can’t be flatter and steeper at the same time, can you? Well, plainly, yes. Kelly’s steeper barrel trajectory at contact is partially a result of his barrel tilting less as he brings it around and into the hitting zone. His swing tilt is 32° this month, the flattest it’s been in any month of the season. That means that he’s bringing the bat flatter through the hitting zone, rather than having the barrel a bit farther below his hands. He’s intentionally going out to create that extra pull and maintain the lift, even though that might open him up to more manipulations of timing

The dynamics of the swing are directly responsible for the increased power output. What’s interesting about this trend, though, is that his actual approach hasn’t changed in the way that one might expect. This is where we get to the idea of “selling out” for power as an oversimplification—at least in the sense that we can’t blindly call it that.

Kelly’s swing rate is actually at its lowest rate in an individual month this season (40.2%). His chase rate did jump a fair bit in August, but has since come back down (21.1%). You’d expect a player who was legitimately selling out to end up being a little bit more aggressive than we’ve seen Kelly in this most recent stretch. That side of the approach would leave us hesitant to make any kind of declaration about selling out, except for one extremely important factor that we’ve neglected to mention.

Kelly’s whiff rate has skyrocketed. At 29.7%, it’s at its highest point of the year, easily eclipsing the 24.5% mark from June. It is, of course, manifesting on the chase side (half his swings on balls out of the zone are coming up empty), but where it’s especially prominent is inside the strike zone. Within the zone, Kelly is swinging and missing at a 24.1% rate. That’s a stark figure, and his highest in an individual stretch since September 2019.

Cruciall, all of this is still happening over a very small sample. We’re talking about 38 plate appearances or, in the case of September on its own, 26 of them. The primary concern is what it’s doing to his walk rate, where he’s now doing under 8 percent of the time, despite the low swing rate we just touched on. When you whiff as much as he’s whiffing right now, you can’t always fight off the pivotal pitch and earn an eventual free pass. Nor is swinging as steeply and hitting the ball as high as he is right now conducive to getting hits on balls in play. That’s, in turn, feeding into his .263 OBP over this stretch (which is also partially pinned down by a .143 BABIP).

If there is a certainty in all of this, it’s that we need more data to not only see this as a surefire trend, but also consider the impact of such a trend within the current iteration of the Cubs’ offensive production.