Illustration: Kevin Jeffers/The Colorado Sun

Story first appeared in:

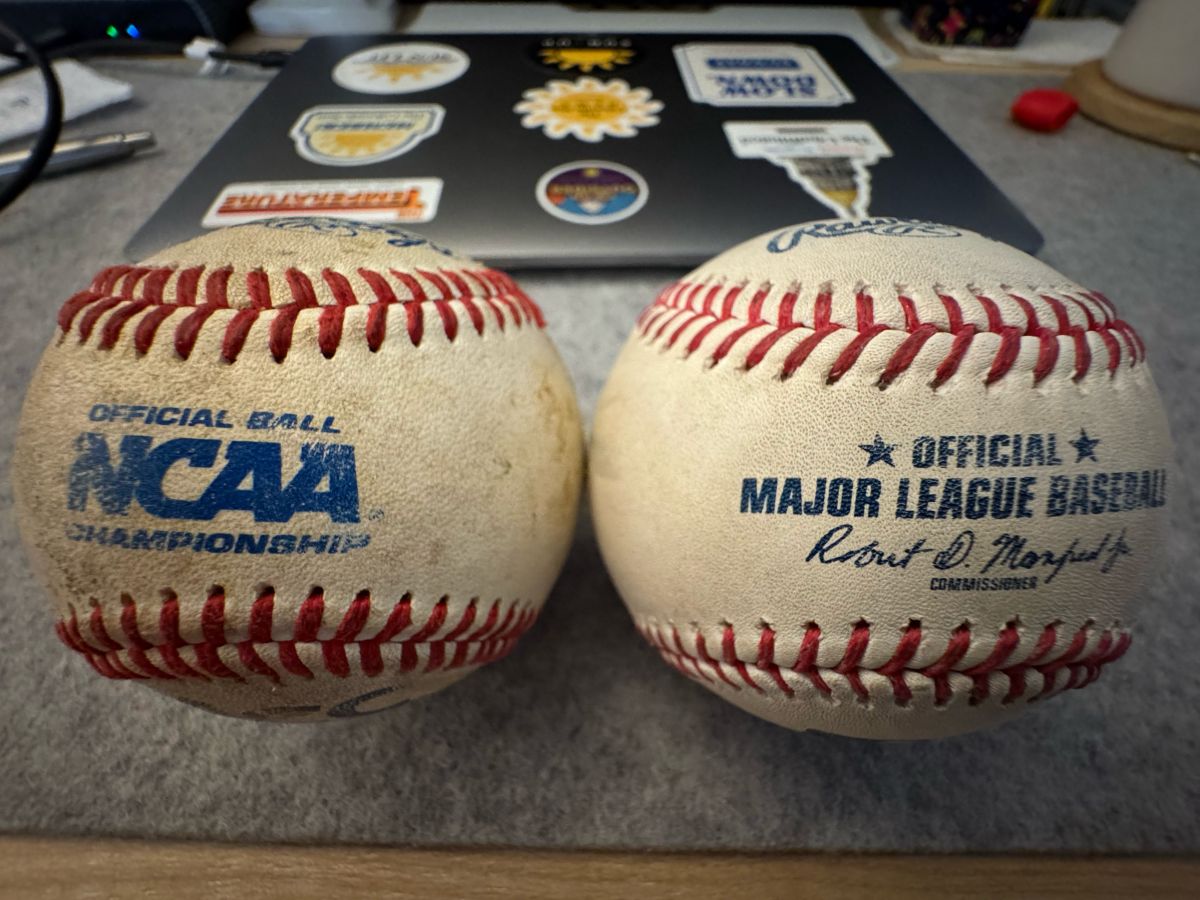

Last month, on a day when the Colorado Rockies gave up eight home runs in a record-breaking loss amid a season of historic futility, I sat at my desk and held two baseballs in my hands.

Apart from some logos, they looked almost identical. Both weighed 5.1 ounces, within the official range for a ball. Both were made by Rawlings, the official manufacturer for Major League Baseball.

But there was one easily noticeable difference with my eyes closed. The ball in my left hand, which was used in a game last season at Coors Field, had flat seams that my fingers spilled over like water over river rock. The ball in my right hand, which was used in a college baseball game a dozen years ago, had raised seams, grippy like a mountain ledge.

Two baseballs, one key difference: Slightly higher seams on the old NCAA ball. (John Ingold, The Colorado Sun

Two baseballs, one key difference: Slightly higher seams on the old NCAA ball. (John Ingold, The Colorado Sun

The difference between the two seam heights was maybe half a millimeter. Two one-hundredths of an inch.

But as I looked at the box score from that day’s latest LoDo letdown, I asked myself: Could this be the key to bringing winning baseball to Denver? Might two one-hundredths of an inch really be all it takes to fix the Colorado Rockies?

Crazy enough to work?

But let’s back up. I’m not here just to talk about baseball. I also want to talk about folly.

In 2009, while covering the state legislature, I walked into a committee room and listened to a man propose something absolutely bonkers.

His name was Gary Hausler, and he was a rancher from Gunnison. His entire adult life had been spent fighting to protect his community’s water from thirsty Front Range cities. As the cities grew and the Western Slope dried, the battle had become especially difficult.

Do you have a big idea for fixing the Colorado Rockies? Send it to johningold@coloradosun.com with your name, hometown and a brief description of why you think it could work. We’ll collect readers’ ideas for a future story.

But Hausler had a plan. Colorado, he told the assembled lawmakers that day, should build a pipeline to import water from the Mississippi River.

As preposterous as the idea sounded, the specifics were even more incredible: The pipeline would need to be 18 feet in diameter and 1,200 miles long, cutting across literally hundreds of jurisdictions. It would require power plants with a Hoover Dam-like generating capacity to push the water up 7,000 vertical feet along its journey.

Its estimated cost was $22.5 billion. (That’s close to $35 billion in today’s dollars, or about double what the state spends out of its general fund per year.)

As an idea, it seemed like pure folly.

Except, here’s the thing: What was everybody else’s plan?

At the time, Colorado had forecasts projecting future water shortfalls of hundreds of thousands of acre-feet per year, and proposals of incremental ways to save water here and there.

That shortfall still looms, larger now, but 16 years later the state doesn’t yet have a plan for how it would respond to, say, mandatory water cuts from the Colorado River.

So whose plan was actually bonkers?

As Hausler said that day, “When I started out, people laughed in my face a lot. That doesn’t happen near as much now.”

There’s volumes that have been written about this concept of crazy-enough-to-work ideas. A few years ago, a book called “Loonshots” that argued for the power of audacious ideas became a modest sensation within the world of startup founders and business leaders. But it’s hardly alone.

Just in the past decade there’s been “The Right Kind of Crazy,” “Moonshot: A NASA Astronaut’s Guide To Achieving The Impossible,” and “Weird: The Power of Being an Outsider in an Insider World,” among many, many others.

“Any idea that is removed from the status quo will always seem like a crazy idea to others,” one author wrote in a piece for the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. “Don’t let a lukewarm response dissuade you from going after your dream.”

So it’s time to step up to the plate, Colorado Rockies fans.

Our team is a laughingstock of the major leagues. No team in the big leagues has lost more games over the past four seasons. Just this year, we’ve set at least five modern-era records for being bad at baseball.

At one point in the season, a catcher — a catcher! — was among our best pitchers. We have been collectively outscored this season by more runs — 394 and counting — than any other team in modern baseball history.

And the Rockies’ response to this crisis? The team’s owners, the Monfort brothers, are vigorously pushing for a league-wide salary cap, while the team’s baseball leaders are talking about continuing to do what they’re doing, just better.

“The Rockies are a young team that is pushing every night to win ballgames and learning, and never giving in and moving forward to someday, hopefully soon in the near future, being a winning ballclub,” Rockies interim manager Warren Schaeffer told MLB.com this month.

“It’s about the process, 100%,” he continued. “If your process is going to be adjusted or altered for a negative goal, you’re missing out on what you can be doing in terms of positive goals when you’re pushing forward.”

Amid the team’s third consecutive 100-loss season, its seventh consecutive losing season, you would be forgiven for rolling your eyes at that comment. As a particularly scathing piece on the Rockies in Baseball Prospectus a couple years ago put it, “That’s not a strategy, it’s a tautology. Everybody is trying to do that.”

It’s time to think big. It’s time to take a swing with our wildest, most outlandish, most harebrained ideas for fixing the team. Because the only true folly would be to keep trying to fix the problem through small improvements.

I’ll go first: For home games, the Rockies should be allowed to use baseballs with bigger seams to adjust for the effects of altitude.

The science

At this point, I want to introduce you to a couple of fellow dreamers.

Meet Alan Nathan and Lloyd Smith, your new favorite baseball nerds. Nathan is an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Illinois who has an expertise in the physics of baseball and a long history of tackling science-related questions for the MLB.

Smith is an engineering professor at Washington State University, where he’s built a niche testing bats and balls. The guy who debunked the idea of juiced baseballs a few years back? That’s Smith.

Together with a few other colleagues, they traveled to Houston in January 2014 and set up an experiment under the closed roof of what was then called Minute Maid Park. They took a custom-made pitching machine, cranked it up to 11, pointed it toward the sky and began launching baseballs into the outfield.

But not just any baseballs.

The balls they used were sorted into three groups by seam height — low, medium and high. The low-seam balls had stitching that was essentially flat, like what is used by Major League Baseball. The high-seam balls had raised stitching. This type of ball, like the one I held last month, was used in the college game up until 2015, when the NCAA switched to a flat-seam ball to increase home runs. (It worked.)

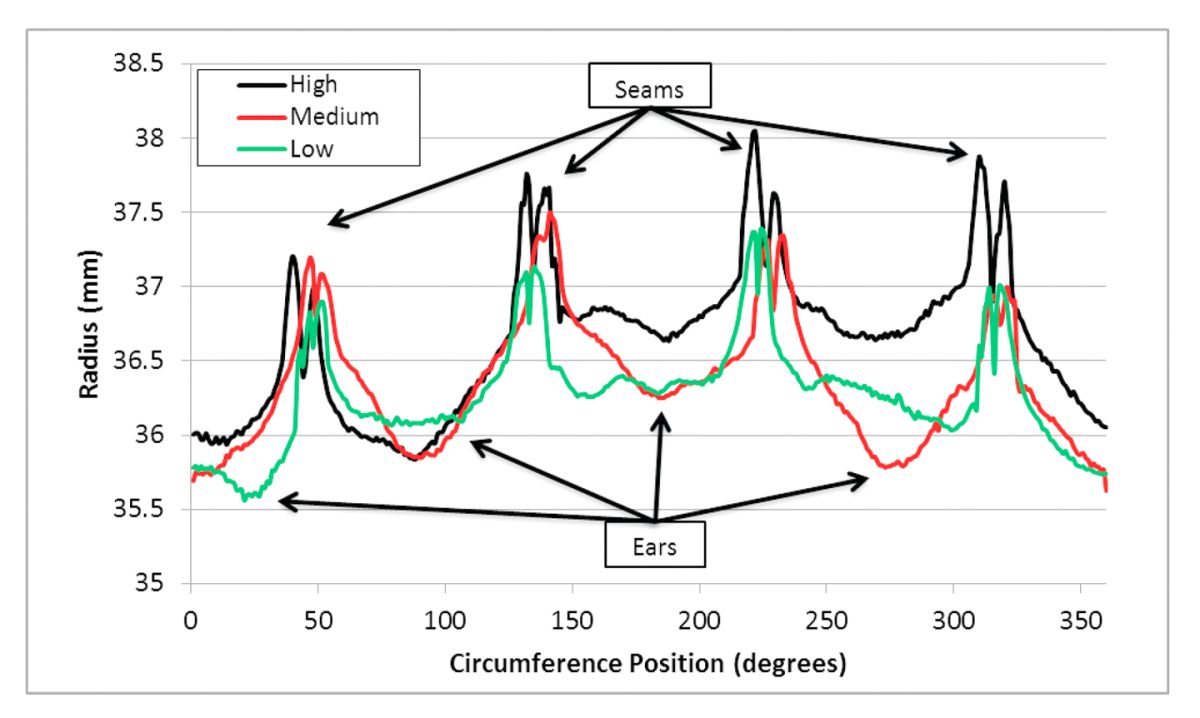

This graphic shows the differences in seam heights of baseballs with low, medium and high seams used in the study by Alan Nathan and Lloyd Smith. (Screenshot of study provided by Alan Nathan)

This graphic shows the differences in seam heights of baseballs with low, medium and high seams used in the study by Alan Nathan and Lloyd Smith. (Screenshot of study provided by Alan Nathan)

Using a tape measure, Nathan and Smith recorded how far each ball flew when launched from the pitching machine. What they found was a clear distribution pattern.

“The largest seam heights yielded the shortest carry distance and highest drag,” they wrote in their subsequent paper on the experiment. “The smallest seam heights yielded the longest carry distance and (lowest) drag.”

And this wasn’t a small effect.

On average, the low-seam Major League balls the researchers launched flew 8.4% farther than the high-seam college balls. This translated into an extra 9.1 meters — nearly 30 feet. Their drag coefficients, essentially a measure of how smoothly the balls flew through the air, differed by 23.5%.

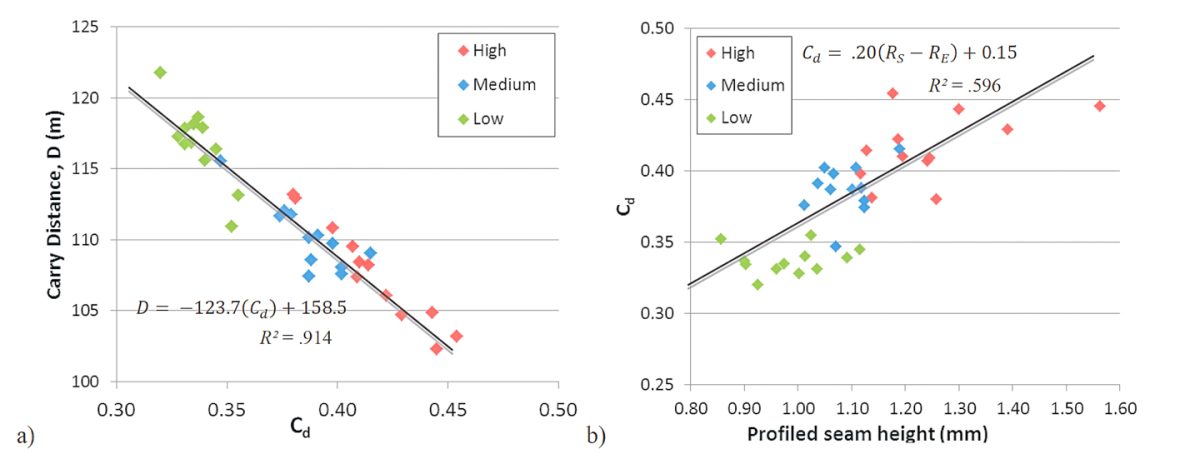

These charts from a study by Alan Nathan and Lloyd Smith show the relationship between a baseball’s seam height, drag coefficient and carry distance. The chart on the right shows that drag coefficient increases with seam height. The chart on the left shows that carry distance decreases with drag coefficient. (Screenshot of study provided by Alan Nathan)

These charts from a study by Alan Nathan and Lloyd Smith show the relationship between a baseball’s seam height, drag coefficient and carry distance. The chart on the right shows that drag coefficient increases with seam height. The chart on the left shows that carry distance decreases with drag coefficient. (Screenshot of study provided by Alan Nathan)

An individual baseball’s aerodynamics include a lot of factors beyond seam height. How perfectly round is it? How rough is the surface? How much mud has been smeared onto it for grip? So, to control for the variability among all the baseballs they used, Nathan and Smith repeated their experiment using a single high-seam ball and a single low-seam ball launched over and over again.

This time, the low-seam big-league ball flew an average of 40 feet farther — 12.4%.

In addition to that, though not something Nathan and Smith measured, the raised-seam baseballs would also likely curve more when spun, another impact of their chunkier aerodynamics.

“When you raise the seam, you increase the drag coefficient,” Smith told me recently. “But you also increase the lift coefficient, and the lift coefficient is what gives you movement.”

Eureka.

Colorado Rockies fans watch in disbelief late in a game against Arizona in 2023 at Coors Field. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

Colorado Rockies fans watch in disbelief late in a game against Arizona in 2023 at Coors Field. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

The altitude problem

What does this have to do with the Colorado Rockies?

These dynamics — how far a ball carries and how much it moves when spun — are essentially the bane of Blake Street. In the less-dense air of a mile above sea level, baseballs just move differently.

The physics can get quite complex. (Who’s ready for a master class on the Magnus Effect?) But the gist is simple: There’s not as much drag on the ball as it flies through the air.

So baseballs in Denver carry farther when hit; they curve and swerve less vertically and horizontally when pitched. Then the team goes on the road and everything resets to normal. Average curveballs suddenly look like monsters, and the bats go cold while hitters adjust.

Take, for instance, a seven-game stretch last month when the Rockies split a home stand against the fearsome Los Angeles Dodgers, scoring 21 runs in the process. In the next series, on the road against the lowly Pittsburgh Pirates, the Rockies scored just once and lost all three games.

“While the offense has made significant strides since the All-Star break,” Denver Post beat reporter Patrick Saunders wrote after the final game against Pittsburgh, “it’s still often a feeble unit away from Coors Field.”

This story first appeared in

Colorado Sunday, a premium magazine newsletter for members.

Experience the best in Colorado news at a slower pace, with thoughtful articles, unique adventures and a reading list that’s a perfect fit for a Sunday morning.

Altitude is the one undefeated opponent across the Rockies’ 32-year history. Yes, the Rockies have had successful seasons before. And, yes, the current team could get better in any number of areas — scouting, drafting, analytics, development, coaching, conditioning. But the team would still have the weight of Denver’s thin air on its shoulders.

“Quite honestly, I don’t know if I’m any closer to the truth than I was 25 years ago,” former General Manager Dan O’Dowd, who built the most successful teams in Rockies history, told MLB.com in an insightful piece earlier this year. “My experience of altitude baseball is just completely one of humility.”

Enter the big idea.

When I recently asked Nathan, the physicist, whether raised seams could effectively create an altitude-adjusted baseball for use in Denver, he didn’t hesitate.

“Seam height would do it,” he said. “There’s absolutely no question.”

“It would decrease home runs, and it would increase movement,” he added.

“As far as I know, no one has ever proposed it before you. It actually would be a very interesting thing to do.”

A player’s proposal

Someone has proposed it before.

In 2023, while working on a story for The Sun’s series examining why the Rockies are so terrible, I stumbled across a now-4-year-old post on the Rockies blog Purple Row. In it, the author advocated for creating a sorting system for Major League baseballs and sending the highest-seam balls to Denver.

The byline on the post has since disappeared, but it was written by a former standout high school pitcher from Parker named Justin Wick. He discovered the idea after stumbling upon social media posts discussing it.

“I just thought what kind of world could this open up — that all of a sudden pitches were moving like they were supposed to,” Wick said recently when I tracked him down.

Justin Wick pitches in a 2019 game for the St. Cloud Rox, a team in a collegiate baseball summer league in Minnesota. (Provided by Justin Wick)

Justin Wick pitches in a 2019 game for the St. Cloud Rox, a team in a collegiate baseball summer league in Minnesota. (Provided by Justin Wick)

“It was as if a bunch of light bulbs were going off in my head.”

Wick doesn’t have a background in physics, but across seasons in high school, junior college, NCAA Division I and summer league baseball, he earned a virtual Ph.D. in pitch movement. Not blessed with a roaring fastball, Wick got outs through clever pitch selection and an unusual side-arm delivery. In other words, he was a thinker, not a thrower.

And he was a studier. The child of school teachers, Wick watched ballgames on television almost every night. When he and his family were able to make it to Coors Field to catch a game in person, it was usually because of who was slated to be the starting pitcher — for the opposing team; the Rockies rarely produced a seat-filling starter.

It was at a tournament in Arizona in high school that Wick first came to appreciate how much altitude affected his own pitching and what he saw at Coors. Suddenly his slider was nasty-good. Hard-hit fly balls were caught on the warning track instead of sailing over the fence.

“It was very cool to feel kind of untouchable,” said Wick, who now works in marketing for the minor-league Sacramento River Cats.

Justin Wick works the crowd as part of his job in marketing for the Sacramento River Cats, the Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants. (Provided by Justin Wick)

Justin Wick works the crowd as part of his job in marketing for the Sacramento River Cats, the Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants. (Provided by Justin Wick)

Wick spent the final years of his college career pitching at Creighton University, though his time on the team came after the NCAA had stopped using the raised-seam baseballs. I asked him if he had ever seen one, and he had, at a tournament in Missouri while in high school.

“Those tore up my fingers for how big those seams were,” he laughed.

But the results spoke for themselves. He was unhittable, embedding a yearslong, enthusiastic fascination of how small changes to the physics of a baseball can have major impacts.

At one point as we spoke, his giddyness bubbled over.

“I have nerded out over this,” he said, “and I’ve never been able to talk about it.”

What will never be

So, now is the part of the story where we hit the brakes.

This will probably never happen.

For starters, Major League Baseball has been working toward creating more standardization, not less. The Rockies’ one, great prior innovation in baseball-tinkering, the humidor, was about making baseballs in Denver physically more similar to those used in lower-elevation, more-humid cities. Now, all MLB ballparks are required to store baseballs in humidors that ensure uniform weight and size.

Nathan, whose research helped lead to the humidor rule, said Major League Baseball is extremely sensitive to allegations it is tampering with the balls to achieve a certain result. Just look at how hard it has worked over the years to dispel allegations that the balls are juiced.

The famous Coors Field humidor is shown before Game 3 of the NLCS in Denver in 2007. The Rockies found baseballs were drying up and shrinking in Denver’s thin air but the humidor keeps them regulation size throughout the season. MLB has since standardized the practice across the league. (AP Photo/Ed Andrieski)

The famous Coors Field humidor is shown before Game 3 of the NLCS in Denver in 2007. The Rockies found baseballs were drying up and shrinking in Denver’s thin air but the humidor keeps them regulation size throughout the season. MLB has since standardized the practice across the league. (AP Photo/Ed Andrieski)

“To have the ball be different in Denver than it is in other places might not be something they would look favorably upon,” he said.

There are also manufacturing challenges. Official Major League baseballs are made only in Costa Rica under strict quality-control standards. All other Rawlings baseballs, including the raised-seam balls formerly used in the college game, are made in China, Smith, the Washington State professor, said.

How would you ensure that a raised-seam ball meets MLB standards for hardness and durability and consistency? Where would you make them?

“You have a practical question of how do you manage this,” Smith said.

And then there’s what Wick noticed. What if pitching with raised-seam balls really does tear up pitchers’ fingers and create a new injury epidemic of blisters?

I emailed Rockies spokesperson Cory Little to ask if the team would ever entertain the idea of proposing a raised-seam ball, but he laid off the pitch.

“When it comes to the baseballs, Major League Baseball oversees the production and distribution of balls across the league, with a standard baseball in every ballpark and every game,” Little responded. “Teams are not able to use specific balls at each ballpark.”

A phone call to Major League Baseball’s media relations department, not surprisingly, went unreturned.

But whether something will actually happen isn’t really the point of an audacious idea. It’s not about predicting what will be. It’s about inspiring visions of what might be.

As Wick put it before we said goodbye, “I felt like this was something that could encourage people to dream and to think and to wonder what could be if something like this happened.”

So, Rockies fans, what do you think could be?

Type of Story: Analysis

Based on factual reporting, although it incorporates the expertise of the journalist and may offer interpretations and conclusions.