Say this for Luke Keaschall: the man knows how to set a high floor for his hitting profile. He has hits in 13 of his 14 games in September, even as the league adapts and adjusts to him. He’s batting over .300 for the month. However, he’s also only walked three times and hit two doubles this month; his slugging average is south of .350.

Is Keaschall proving himself slump-proof, or is this just what a slump looks like for him? That question isn’t answerable in the sample of playing time he’s accrued this year, or that he will accrue before the season is over. It’ll have to wait until next year, and perhaps well into that campaign, at that. There’s little doubt that Keaschall has an elite raw hit tool, at this point. The league is forcing him to adjust and cover a bigger strike zone, though, and whether he can counteradjust will determine just how valuable he is going forward.

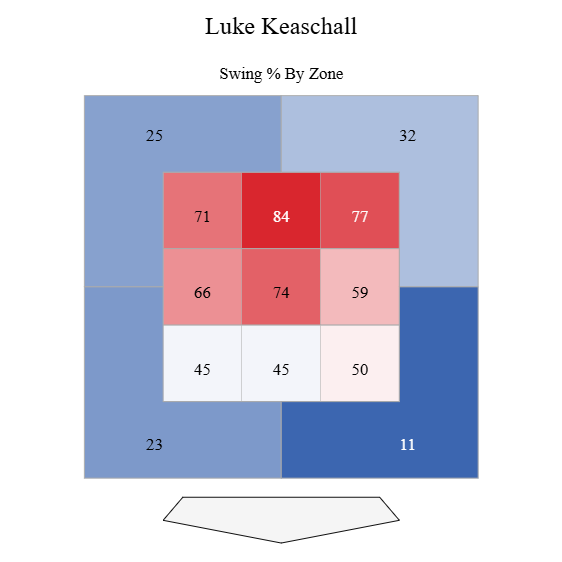

As we’ve discussed before, Keaschall loves to hit the high pitch, despite the steep plane of his swing. He almost cuts off the lower rail of the zone, preferring to gamble on not having strikes called down there than to risk chasing a pitch he can’t handle with his extremely compact stroke.

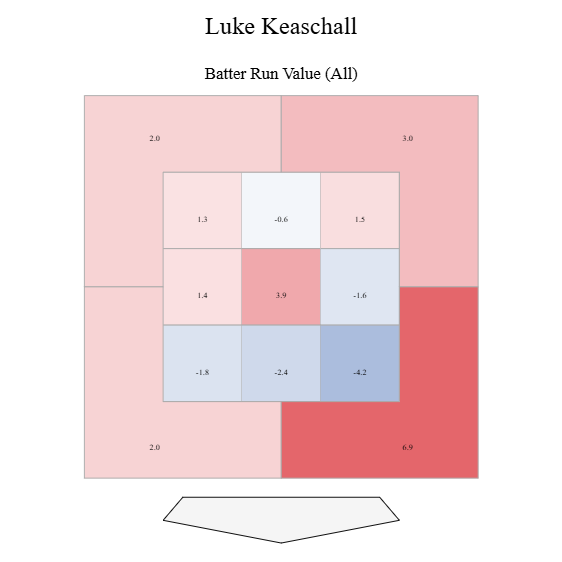

As a result of this, Keaschall does nearly all his damage in the upper, inner quadrant of the strike zone. His most famous hit to date, the walkoff home run he drove to right-center against the Royals in mid-August, was on a pitch up and away, but most of the time, he’s only going to really hurt you if the ball is near the middle of the zone, and a bit in from there. Even most of his well-struck singles come in that part of the zone. Because he takes a bunch of called strikes along the bottom edge and doesn’t get the barrel to the ball if it’s down and away, that lower, outer quadrant is where you’re most likely to get him out. This chart shows his run value per 100 pitches by location.

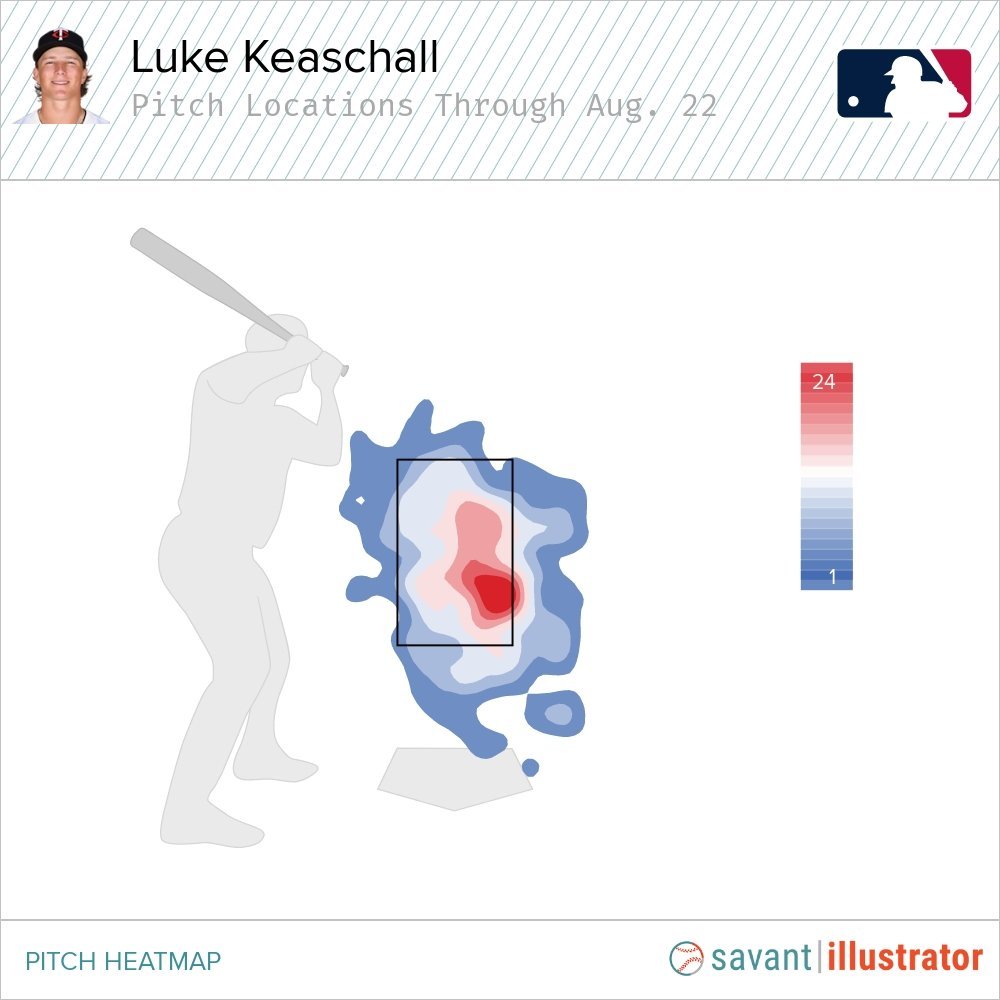

The league has this data, too. Heck, they had it while Keaschall was still in the minors. Thus, pitchers started hammering him away, away, away, practically the moment he came up. If we come as close as we can to splitting his rookie season exactly in half, to date, the dividing line comes August 22. Here’s where Keaschall saw the most pitches through that date.

Away, away, away. Preferably, down and away. Pitchers had the book and they tried to make him prove he could hit that pitch. He still can’t, really.

However, during that span, Keaschall had a .400 weighted on-base average (wOBA, a holistic offensive stat that scales neatly to on-base percentage; .400 is excellent). His average exit velocity was 87.9 miles per hour, and he only struck out 11.1% of the time.

As it turns out, if you spend all your time trying to attack one side of the plate—especially to a hitter who, while he might not have a swing versatile enough to produce hard contact foul line-to-foul line or throughout the zone, does have a strong ability to spoil pitches and the speed to turn a squibber into an infield hit—you’re going to end up making mistakes. The ball will wander into the middle of the plate too much, where it gets hit hard. The hitter, even if he’s a rookie with a fairly stubborn philosophy, can start to cheat toward that pitch and cover it better than he ordinarily would. Keaschall foiled the basic plan of going after the so-called hole in his swing right away.

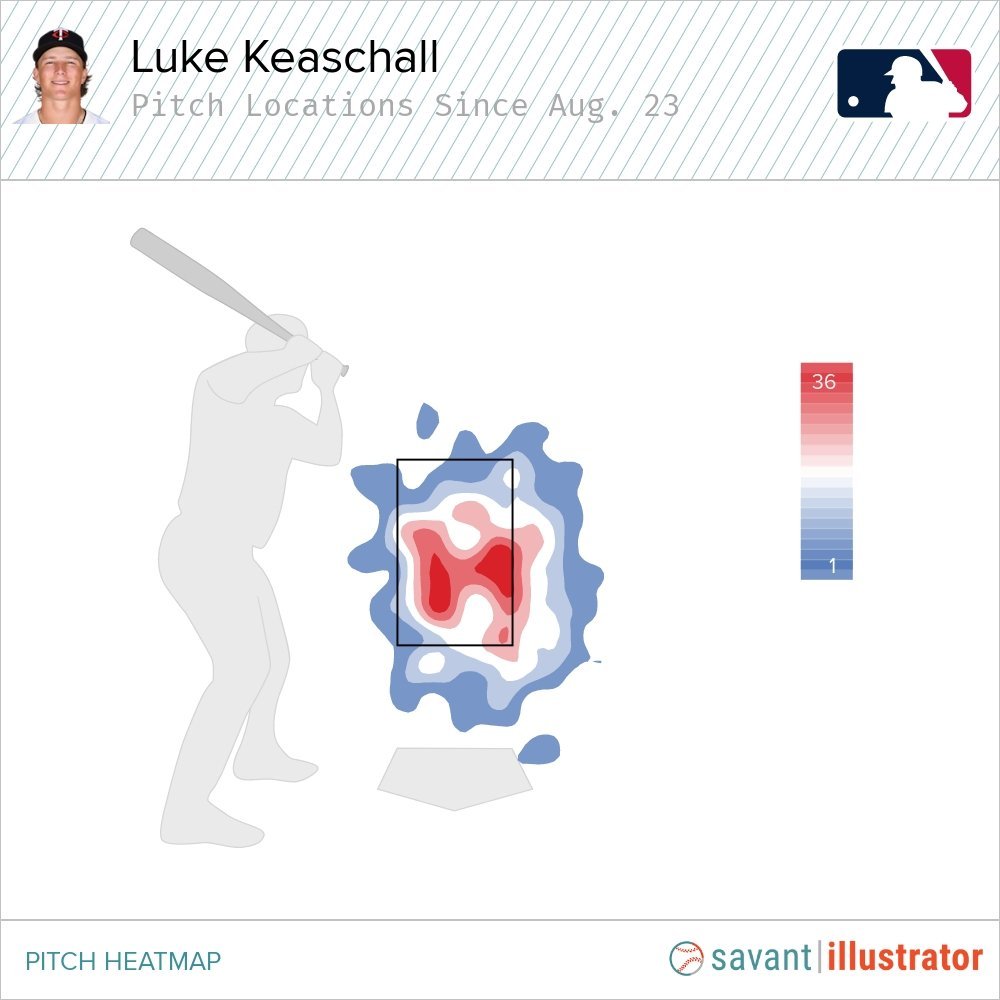

Here’s how pitchers have responded, since August 23.

Wait! Don’t do it! You’re in danger! Except, no, they largely haven’t been. Keaschall’s wOBA is down to .338 during this stretch. His strikeout rate is 15.2%, and even when he puts it in play, his average exit velocity is down to a very unthreatening 84.3 miles per hour. Teasing that outside edge has worked, to some extent, because Keaschall’s chase rate is up from 20% in the first half of his young career to 25% in this second half of it. Mostly, though, the league is making him cover the whole plate, and he’s having a very hard time with that. More pitches on the inner third means being ready to pull the hands in or tilt downhill even more than usual, but to do that, Keaschall has to give up more capacity for covering the outer third. For many pitchers, feeling emboldened to go after him inside also means fewer mistakes over the middle.

Again, so far, Keaschall has only consistently proved that he can punish meatballs in the middle of the zone—and, specifically, hanging stuff in the upper 80s. He doesn’t hit even average fastballs for power, and if a pitch finds its target, he usually fights it off, rather than truly attacking it. That’s not an indictment, per se. There are ‘mistake’ hitters in the Hall of Fame, and Keaschall’s great blend of contact skill and speed allows him some margin for error.

If he wants to be a truly productive hitter, though—a legitimate top-third hitter in a winning lineup, rather than a nice but empty batting average—it’s time to see what Keaschall’s next phase looks like. How he tweaks his swing and/or his approach to put the barrel on the ball more often or produce more bat speed while covering the whole zone will shape his career, and the final 10 games of 2025 will give us a glimpse of that.