Editor’s note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and performance through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

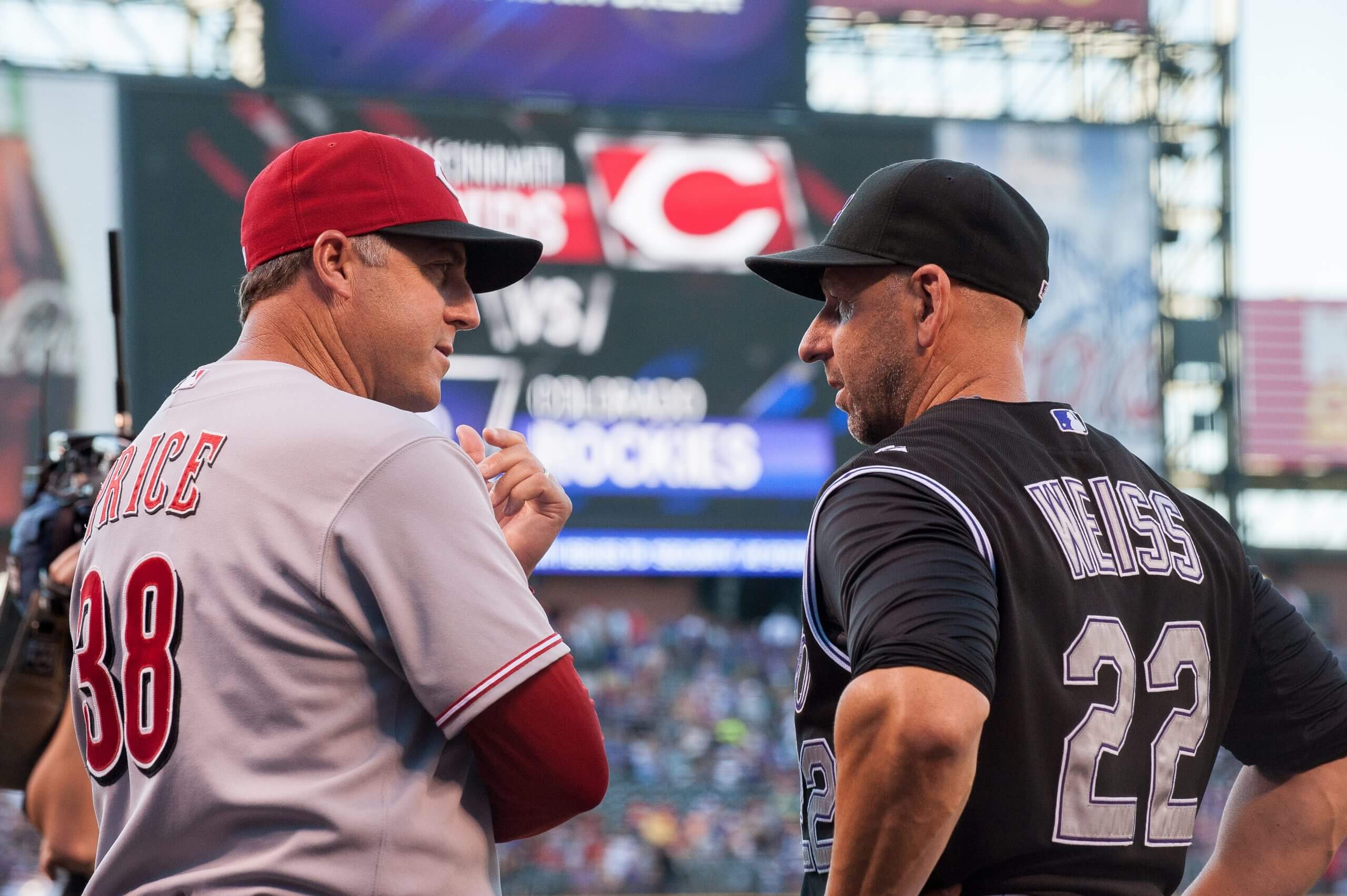

Bryan Price managed the Cincinnati Reds for parts of five seasons from 2014 to April 2018. He was also a pitching coach for the Reds, Arizona Diamondbacks, Philadelphia Phillies, Seattle Mariners and San Francisco Giants.

On my final day managing the Reds in April 2018, we flew from Milwaukee to St. Louis. Dick Williams, the general manager, was traveling with the team, as was Walt Jocketty, an adviser to the owner.

We got on the bus to head to the airport, and Walt was on the bus. That was unusual. So I knew then. When these things happen, you can sense it. You can sense the ice thinning under your feet.

When I got off the bus at the hotel in St. Louis, Dick grabbed me and said, “Hey, I’m going to pop up for a visit.” I understood. We were 3-15, which was completely unacceptable. We had won 42 percent of the games that I had managed. I called my wife and my daughter and gave them the heads-up.

I really appreciated that Walt was there with Dick. He had hired me as a pitching coach in 2010 and as the manager in 2014. Dick was very emotional. That was something else I appreciated. Dick let me know that it had been a rough road, and it was not something personal or that they felt I had an inability to manage. It was just time, which I understood. I understood it fully.

That season was my 19th year in the big leagues. I had spent 16 years in the minors before that. And I had never been fired as a coach before.

You know what I thought after I was fired?

I was grateful for the opportunity.

After my first year managing the Reds, we went into a full rebuild. I’m a realist, which is sometimes a blessing and sometimes a curse. I knew there was a chance I might not get to the other side of the rebuild, so I asked myself: What am I grateful for?

I knew it was going to be a challenge, and I was grateful for the opportunity to be personally challenged in such a way.

How do you maintain positivity? How do you create a culture of unrelenting effort and preparation regardless of results? How do you go through a rebuild and keep the spirits of the players intact?

That became my silver lining and a lesson. I knew I was going to find the best part of who I was — not just as a coach or manager but as a person. Because losing does challenge you. The environment can get prickly. The moves you make are scrutinized daily.

I remember one time when we were in a rain delay, the owner of the Reds, Bob Castellini, came down to my office to visit. He was great. He was very much a straight shooter. We had lost some games at the time, and he looked at me that day and said, “Bryan, I sure wouldn’t want your job.”

To me, it was an impactful acknowledgement. I took it as a badge of honor: to be the person in a position that the owner of the team wouldn’t want to place himself in because of the challenges we faced. That meant a lot to me.

Listen, we all dream of being All-Star players and World Series champion managers. We don’t all get to be those guys. It’s only special because so few accomplish it. Kirk Gibson once told me that he had wished that every player could one day feel the way he felt after hitting his walk-off home run in Game 1 of the World Series. That sentiment from Gibby encapsulated the dream of nearly every person who ever took the field.

But many of us are simply going to go out there and do dirty jobs with optimism and with our heads up the best we can. I had the opportunity to face the things that we all dread and get to the other side of it.

Another lesson I learned: Don’t add unnecessary pressure to an already difficult task. It’s really easy in a manager’s position to say that everything negative that happens is because of a decision you made. That may be too much heightened self-scrutiny.

Jim Riggleman was added to my coaching staff in 2015, and then he became my bench coach the next year. We’d had a few extended losing streaks, and we had a particularly difficult loss where we lost by a run at home. He came in after this loss and said, “You know, Bryan, you can manage a perfect game and still lose.”

He wasn’t saying it to absolve me of accountability. But it underlined the importance of doing the best you can and finding a way to live with the results. If you do your best and have the right processes in place, the right attitude, the right message, you still might not always get the result, and that’s going to have to be all right.

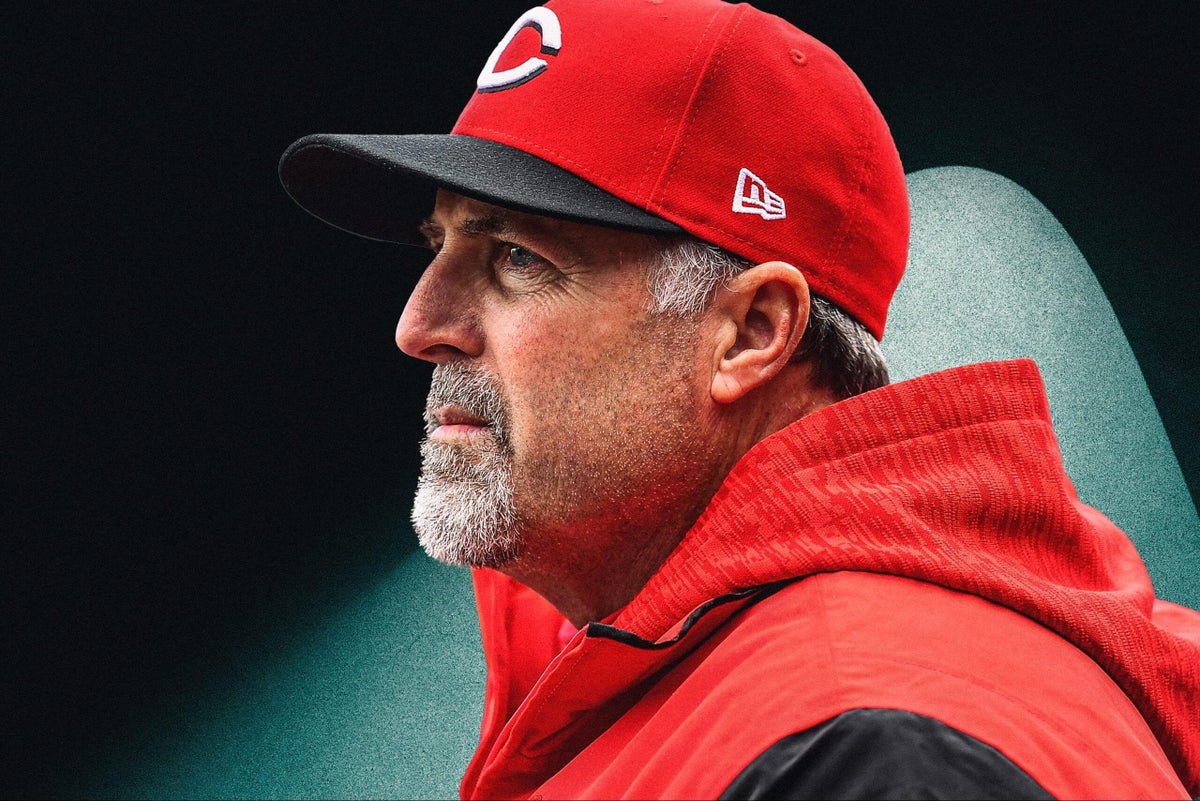

Bryan Price said he learned a lot about himself when he was fired by the Reds in April 2018. (Dustin Bradford / Getty Images)

I’ll tell you another story that shows you what I learned. Back in 2000, I was in my first year as the pitching coach for the Mariners. It was also my first year in the big leagues. We were crushing it in the first half of the season, way ahead in the standings. Then, after the All-Star break, we lost a bunch of games and fell behind Oakland for the division lead.

We were in Detroit and just had the crap knocked out of us. I felt like the whole weight of the world was on me, as our pitching was really struggling. It was as if everyone was looking in the dugout and saying: “Price is screwing up this team. Price can’t get these guys to perform. Price is the one to blame.” I was overwhelmed.

Some of the front-office guys were in town and had planned a staff dinner, and I didn’t go. I was on top of my bed in my hotel room. My mind was racing: I’m screwing this up for the team. I’ve got to do better.

Shortly after that, Lou Piniella, the manager in Seattle, asked my opinion about a pitching change. For the first time ever, I was hesitant. I’d never been on the fence. He didn’t call me out on it, but he said something that made me think: What are you doing?

That moment came into play in 2018, my final year with the Reds. We were in Philadelphia in mid-April, and we were scuffling. I’d used Jared Hughes, a super durable and reliable reliever, two days in a row. We were down 2-1 in the eighth inning, and I had Tanner Rainey on the mound. He was making his major-league debut.

Rainey got in trouble and gave up a grand slam, and we ended up losing 6-1.

When the game was over, I got a call from Dick Williams. That was really unusual. He rarely questioned my player usage. He said: “I was just really wondering why you didn’t use Hughes there in the eighth. We had a chance to win that game.”

That was one of those markers when I understood I probably wasn’t long for this job.

But the reason I made that decision not to use Hughes was because I wasn’t going to use a pitcher three days in a row in April. I thought it was irresponsible, and yet I understood the consequences of that decision. I knew it would be one of those moments that would be easy to second-guess.

The point I’m making: You have to understand that you have a job to do, and you have to trust that the decisions you make are the right ones, even when they don’t always work out.

I have no embarrassment about my time managing the Reds. Zero. That doesn’t mean flying commercial back from St. Louis to Cincinnati and having to go through the airport after the firing was easy. And certainly, there are games and situations that I would do differently if I could.

But I know for sure it was not from a lack of effort or preparation or passion. Because of that, I live with gratitude for having the chance to manage the Cincinnati Reds.

— As told to Jayson Jenks.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic / Joe Sargent / Getty Images)