Caleb Durbin knows what he’s doing. He’s not diving in front of the ball, trying to get hit—there are guys in the league who do that—but he’s smart and tough and fearless enough to stay in front of it if it’s coming right at him. In his rookie campaign, Durbin drew just 30 walks in 506 plate appearances, but he was also hit by pitches 24 times. If, as they say, a walk is as good as a single, a plunking is also as good as a walk, and Durbin’s .334 on-base percentage owes much to the fact that he was as likely to catch the ball with his body as to his actual plate discipline. He struck out just 9.9% of the time, and that, too, can be attributed partially to his proclivity for getting in the way; he would often get hit before a pitcher could work their way to the depth of count required.

By and large, fans and analysts alike discount the skill of getting hit by pitches—and not without reason. Drawing walks by making superb swing decisions is more valuable, because it’s more likely to unlock other dimensions of offensive value—hitting for average and power, for instance. Durbin did make good swing decisions this year, but not exceptionally good ones. He didn’t draw walks at a good rate, except insofar as you give him full credit for his reaches via plunk. There’s also a question of how often one can get hit by pitches without getting hurt, and there’s undeniably a correlation between getting hit a lot and missing time due to injuries.

Finally, there’s the question of whether getting hit is a sustainable skill. Talking about Durbin (who had, just then, been sidelined as a precaution after being hit in the arm twice in as many days) back in spring training, his manager vowed that it is.

“It’s a skill. Not moving,” Pat Murphy said, on March 9. “And for certain, not being an early move. The guys that can hang in, turn their head, as opposed to getting out of there.”

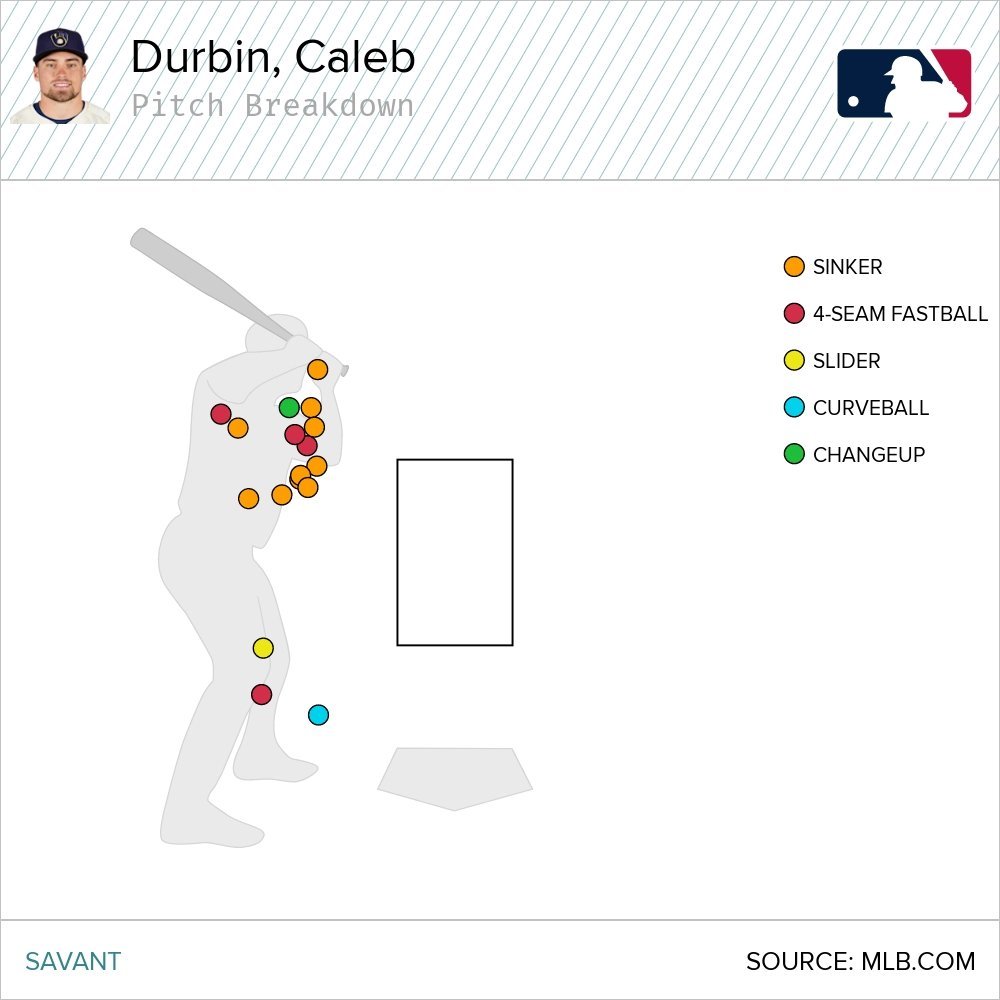

That, indeed, seems to be how Durbin does it. The main question underlying a debate about the stickiness of the skill of getting hit is: will pitchers throw enough balls close to you for the opportunities to get hit to even arise? Durbin’s style answers that question. Only 35 (1.9%) of the pitches he saw this year were way inside, in the areas labeled “Waste” pitches by Statcast because they’re so far in on a righty batter. That’s roughly average. However, he got hit by 17 of those pitches, a whopping 48.6% of his chances. Not only is that the highest rate among right-handed batters, but the second-best number was 31.1%. The difference between Durbin and second place, on a list of 122 qualifying righty bats, is as large as the difference between second place and 32nd. Here’s a chart showing the location of those 17 times when he didn’t move.

You’re probably noticing that 17 is not 24. Yes, Durbin also got hit seven times on balls closer to the zone, though the frequency at which he was hit on such pitches was not nearly as unusual as the rate at which he was hit on the ones farther in.

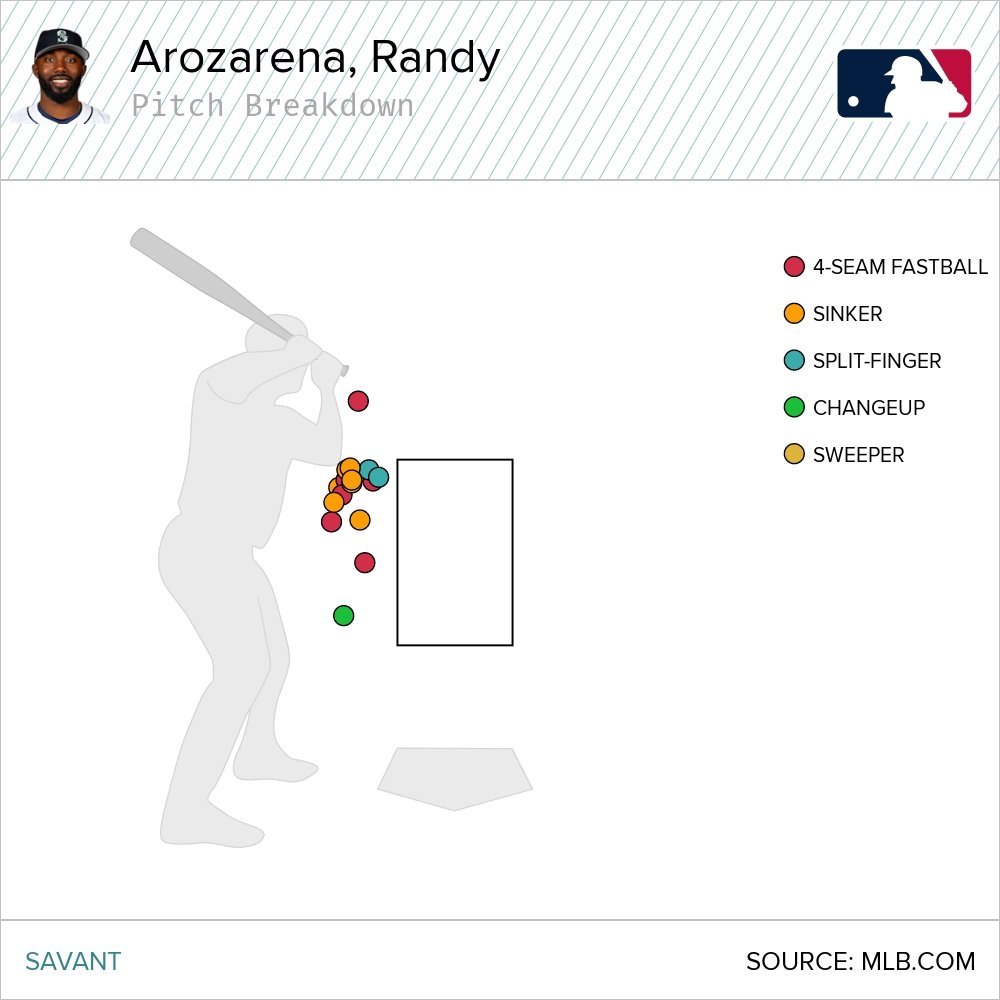

Again, Durbin’s not necessarily trying to get hit. It’s about going up there willing to accept being hit, just as one must be willing to accept walks even while looking to hit the ball. Trying to get hit looks like this. Randy Arozarena is the only batter who was hit more times than Durbin, overall (although in roughly 200 more plate appearances), and 16 of his 27 plunkings came when he crowded the plate (often with two strikes) and wore one semi-intentionally, even when the ball was close to the zone.

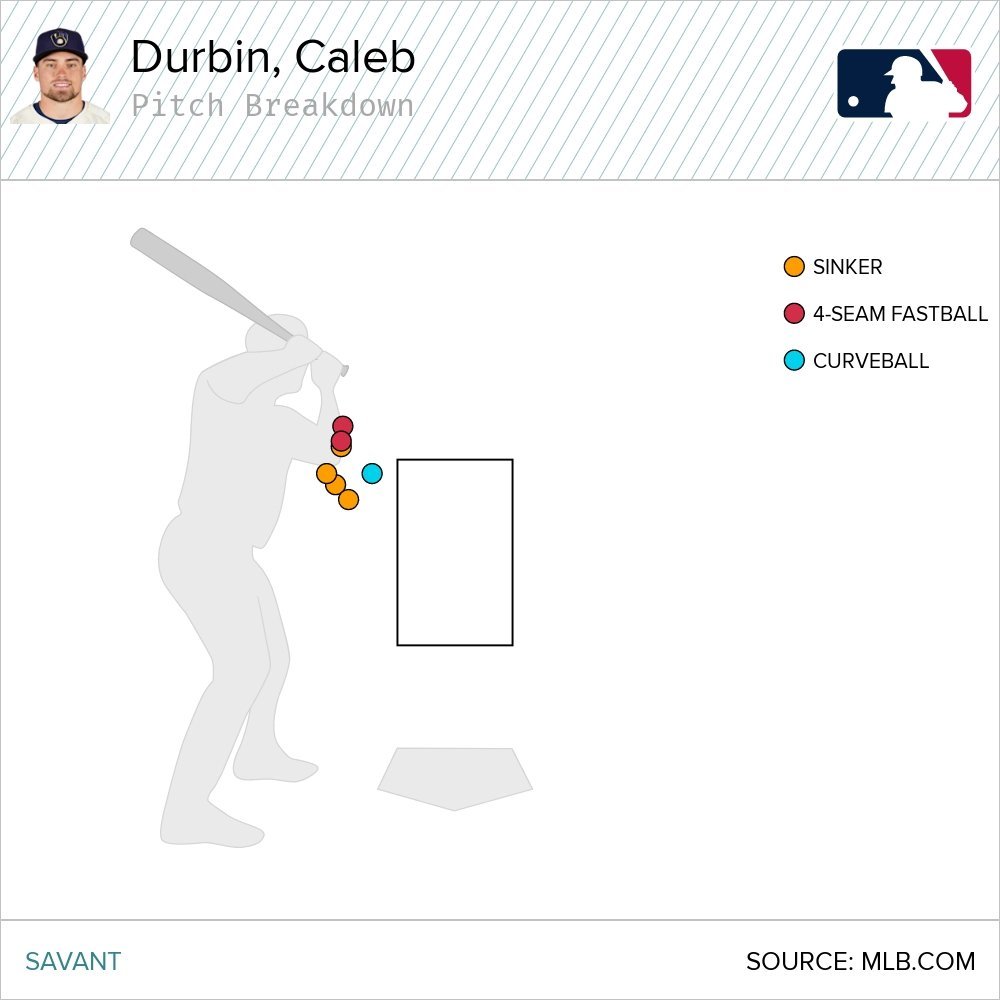

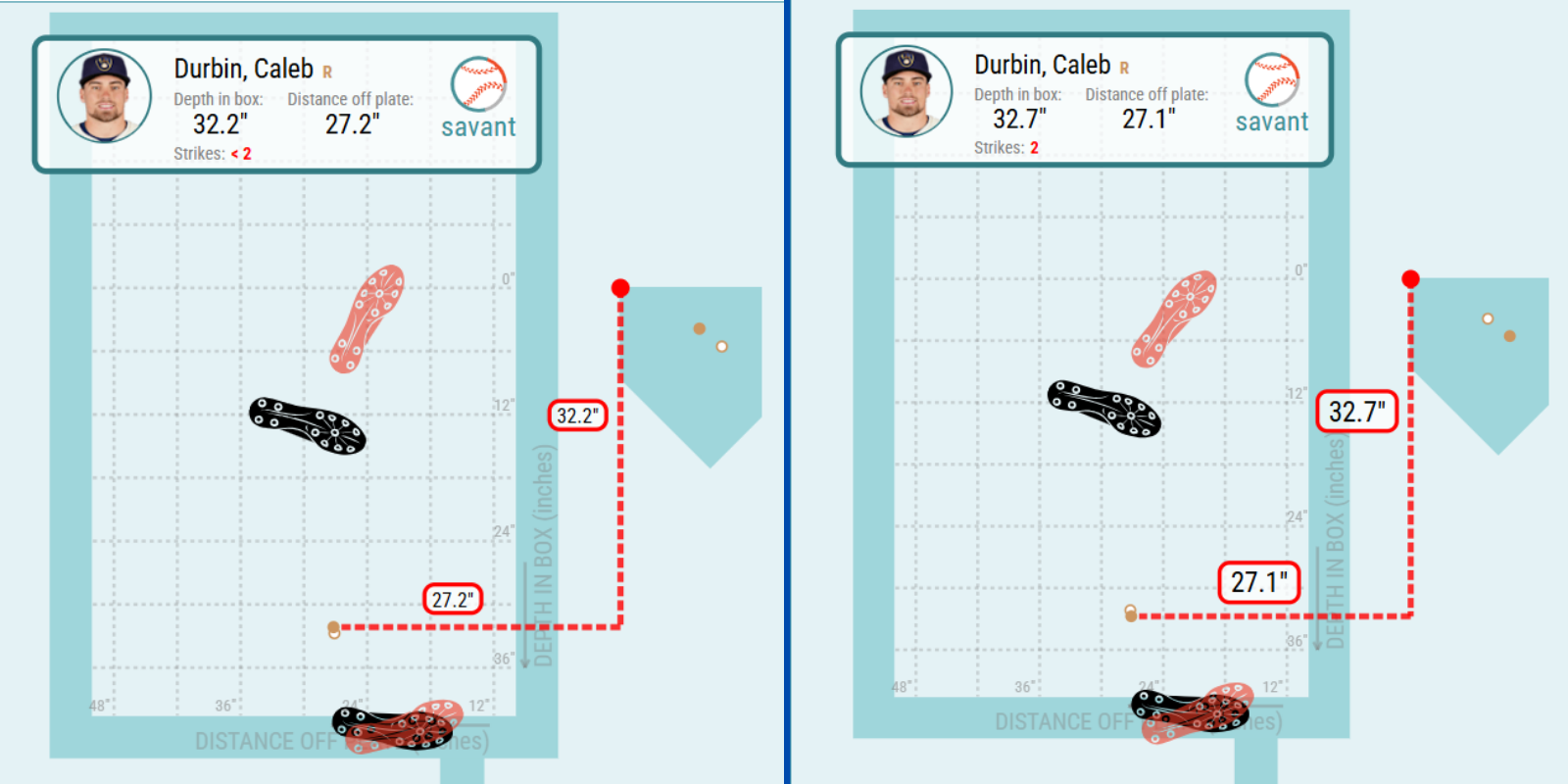

Durbin is more subtle. Murphy’s characterization of it in March was perfect: the art lies in simply not moving out of the way. If one doesn’t make at least half a vague effort to do so, the umpire can cancel the award of first base, but that hardly ever happens. Besides, Durbin is a good actor. He naturally opens up a bit early, because he wants to get around the ball inside and pull it, but he doesn’t step into the bucket. Especially with two strikes, he stays in line and close to the plate, and he lets the natural, linear movement of his swing carry him into the ball instead of away from it. He can make a show of trying to get out of the way, then, without having any real chance to do so.

Staying home that way also lets Durbin cover the outer third of the plate well, especially in two-strike counts. The danger that he’ll get hurt is real, and isn’t going anywhere. He’s always shown a willingness to wear one, within reason, but he didn’t get hit this much in the minors. The combined influences of Murphy and plunkmaster-turned-coach Rickie Weeks might have helped him learn to embrace this aspect of his game, but in the process, he might also have taken a few more bruises than is wise. He hasn’t run as well or as often as one might have anticipated, when he was stealing at almost every opportunity last year. Some of that is that it’s harder to run against big-league batteries, but another part is that his body has taken a pounding.

Nonetheless, on balance, you have to give Durbin real credit for all the thwacks he’s absorbed in the name of getting on base. He’s a great complementary piece in the Brewers lineup. Only William Contreras had a higher Win Probability Added than Durbin this year, thanks in no small part to those times when he was hit by pitches to extend rallies or get himself out of a count in which the pitcher was ahead. This skill is real, and can be immensely valuable. It comes with difficulties and tradeoffs, but that’s part of baseball. As long as Durbin remains willing to stay in front of a ball flying at him, he’ll hold onto a significant source of offensive value. It might even be the kind of small thing that becomes big at some point during the Brewers’ playoff run.