By Al Doyle

Except for double play situations, the concept of pitching to contact – as in efficiently inducing outs through grounders, popups and harmless fly balls – is nearly extinct in modern baseball.

This style of pitching is often associated with soft tossers, but even guys with above-average velocity would go for quick outs in the past. Hall of Famer Jim Palmer is a prime example. “The best pitch is an inch off the plate,” he said. That philosophy of working the corners – and having eight-time Gold Glover Paul Blair in centerfield – meant 266-game winner Palmer was the master of soft and routine flyouts. He never gave up a grand slam in 3,948 career innings.

Does getting through an entire season of excellence with almost no Ks or walks sound impossible? Don’t tell that to Harry “Slim” Sallee.

The left-hander had his best season by going 21-7 with a 2.06 ERA (136 ERA+) for the world champion 1919 Cincinnati Reds. That fine stat line isn’t the most noteworthy part of Sallee’s career year. He dominated while striking out just 24 in 227.2 innings pitched, or less than a whiff (0.949) per 9 innings pitched. Opposing hitters had to come up swinging, as Sallee’s miserly 20 walks works out to 0.79 for every 9 IP. Sallee is one of seven post-1900 hurlers with more wins (at least 10 Ws) than bases on balls.

Using numbers per 9 innings is an appropriate way to analyze Sallee’s unique performance, as he tossed 22 complete games in 28 starts with a lone no-decision. Slim’s only relief appearance resulted in a win despite giving up two earned runs and four hits in 3 IP against the Boston Braves on July 30. This 21-game winner didn’t appear until the 10th game of the season and had a few longer-than-normal stretches between starts, indicating the possibility of nagging injuries.

This was done by a pitcher who started with both feet on the rubber. Being extremely tall for the era at 6-3 provided an advantage, but it was Sallee’s multiple release points and arm angles that confounded the opposition. Strikeouts were much lower in the pre-1920 Dead Ball era, but even that doesn’t reduce how mind-boggling Slim’s 1919 starts are and how he dominated hitters who almost always made contact.

Sallee tossed six games with no Ks or walks along, with another 13 starts with a lone strikeout or free pass – but not both. Weird numbers fans will want to check the 13-hit July 17 complete game at Ebbets Field against the Brooklyn Robins. Sallee improved to 10-3 in the 5-1 Reds win. Cincinnati turned just one double play, so the lefty was often pitching with Robins runners on base.

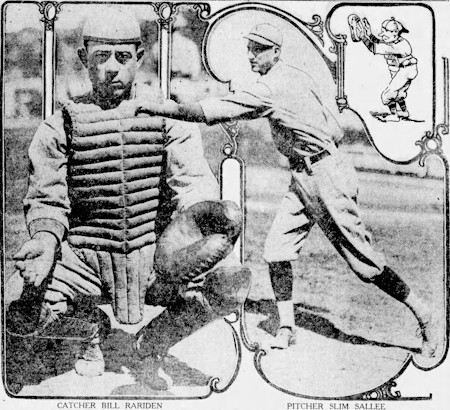

The battery for the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series: Catcher Bill Rariden and pitcher Slim Sallee. Source: San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1919.

The battery for the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series: Catcher Bill Rariden and pitcher Slim Sallee. Source: San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1919.

Then there was the 14-hit 4-2 complete game road victory against the Cubs on September 1 that boosted Sallee’s record to 17-6. Cincinnati turned a lone double play, so Sallee had to finesse his way through a parade of Cubs baserunners. Since Slim’s strikeouts were a rare event, was he a master of inducing double plays? There were 23 double plays in 28 starts, or 0.79 per game. If that sounds low for the ultimate pitch-to-contact season, it was merely 11.4 percent above average.

The 1919 Reds ranked fourth in the eight-team National League with 98 double plays in 140 games, or 0.70 per contest. Shouldn’t there have been more twin killings during the Dead Ball years? Unlike today, teams often went for a sacrifice bunt with a runner on first or first and second with less than two outs. That reduced double-play opportunities. A softer ball also meant many grounders trickled to infielders who could only get one out. Compare that to today’s sharply hit balls that give fielders adequate time to turn two. Dinky early 1900s gloves resulted in more infield hits and errors. Additionally, some teams used sheep and goats to help trim the grass, and the primitive-by-today’s-standards groundskeeping meant bad hop hits were a regular occurrence.

Most ballgames in 1919 were played in an hour and 40 minutes to two hours and 15 minutes. That pace was too leisurely for Sallee. Nine of his starts were wrapped up in 1:30 (90 minutes) or less. The most amazing quick performance came at home on September 21. “Sallee Day” attracted a solid crowd of 10,000. Even though the guest of honor lost 3-1 to Brooklyn, the game took a breathtaking 55 minutes. The lesson is obvious. Never arrive late when Sallee was on the mound.

Cincinnati made its first World Series appearance against the infamous Chicago White (Black) Sox. Many believe that an honest effort by the Sox would have led to an easy victory in the best of 9 Series, but the 1919 Reds were a top-notch team, as shown by their 96-44 (.686 winning percentage) record. That was six games better than the 88-52 (.629) White Sox regular season.

In addition to Sallee, the Reds had a group of formidable starters. Dutch Ruether went 19-6 with a 1.82 ERA (154 ERA+), Fellow 19-game winner Hod Eller had the rotation’s highest ERA at 2.39 for a 117 ERA+. Right-hander Ray Fisher put in one of the finest performances ever by a back of the rotation starter by going 14-5 with a 2.17 ERA (129 ERA+). Swingman Jimmy Ring deserved a better record than 10-9, as his 2.26 ERA was 24 percent better than the National League norm.

Sallee had a typical performance in Game 2 of the Series, as he tossed a 10-hit complete game in a 4-2 victory over the Black Sox. Slim struck out a pair with a lone walk. He got a quick hook (by 1919 standards) in Game 7. Sallee pitched 4.1 innings while giving up four runs. Two of those runs were unearned, as the Reds committed four errors in a sloppy performance. Sallee finished this eight-game World Series with a 1-1 record and a 1.35 ERA in 13.1 IP.

It’s safe to say that no starting pitcher will come within light years of Slim Sallee’s incredible season of constantly getting hitters out through soft contact.

Follow me on Instagram: @rip_mlb

Follow me on Facebook: ripbaseball

Follow me on Bluesky: @ripmlb

Follow me on Threads: @rip_mlb

Discover more from RIP Baseball

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Published by Sam Gazdziak