Seam-shifted wake has been a hot topic for baseball nerds over the last few years. Thanks to rapid advancements in the quality of pitch-tracking information, we can now quantify this movement, in addition to the spin-related movement of a pitch. These two types of movement are also known as Magnus movement (spin-related movement) and non-Magnus movement (aka seam position-related movement).

The name comes from Heinrich Gustav Magnus, who concluded that when a spinning ball moves through the air, it creates a force that makes it curve away from its straight-line path. The spin changes the amount of friction the air can impart on the ball, and thus alters the effect it has on the ball’s flight, relative to what the flow of air across a non-spinning surface would have.

Magnus movement is everywhere in sports—especially in baseball. A curveball has topspin, causing the ball to bite downward, while a four-seam fastball has backspin that helps the ball resist gravity and gives the appearance (to a hitter) of rising action. The best example, perhaps, is this YouTube video demonstrating how a basketball (which doesn’t have the same raised seams as a baseball, and therefore doesn’t have the same non-Magnus effect) reacts when dropped off a dam with no spin, and then with backspin:

There are some variables here that don’t apply to baseball, but it’s perfect for showing one thing: spin affects how a ball moves.

Baseballs are vastly different than basketballs, though, because of those seams. While spinning a ball alters how a pitch moves by reducing its friction with the air around it, the baseball’s seams increase how the air can affect the ball. A perfectly round object would not encounter any seam-shifted wake, but the protruding seams create an alternative force on the ball in addition to its spin, and often in a different direction. In baseball history, many pitchers have attempted to scuff balls or spit on them to gain some unexpected movement on their pitches, so the existence of this movement is not a new phenomenon, but modern pitchers have found ways to capitalize on the seam position to devastating effect.

The reason for this non-Magnus movement (or seam-shifted wake) being so useful is that hitters have no way to see what’s coming, unless they’ve faced that pitch before. While hitters have been trained to identify spin to anticipate the pitch that’s been thrown and anticipate how it will move, accounting for non-Magnus movement is a whole different problem.

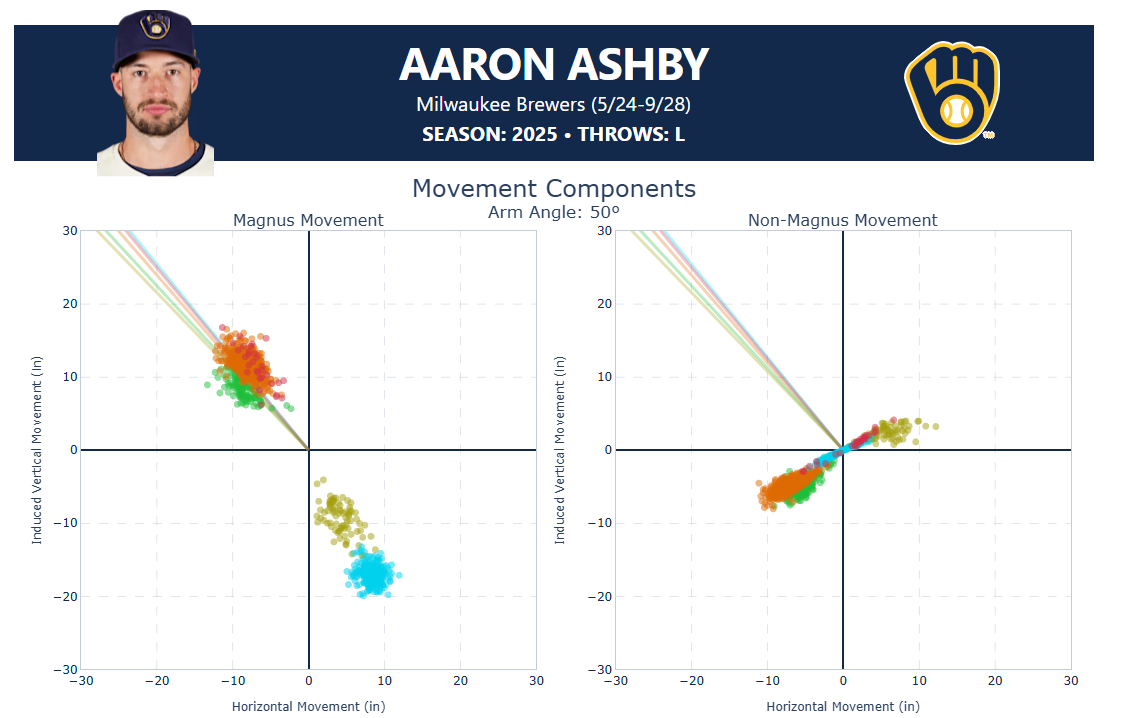

Aaron Ashby is a prime example. He has one of the straightest four-seam fastballs in the game, struggling to generate the riding life that usually defines that offering. However, he boasts one of the best sinkers in the game, with extremely heavy action.

The interesting thing is that the spin-based movement (on the left) of his four-seam fastball (red) and his sinker (orange) is not dissimilar. Where he excels is in how he uses the seams to generate up to 10 inches of additional horizontal break and 5-8 inches of vertical drop when he throws a sinker, compared with expectation. This partially explains why hitters struggle to pick up Ashby’s four-seam fastball on the rare occasions when he does use it, and why they have a ground ball rate of 65% against it. The ball just keeps dropping on them, in ways that their spin-trained eyes don’t expect.

You can see from Ashby’s profile that he gets a lot of “unexpected movement” on his slider, sinker and changeup, all three of which had above-average swing-and-miss rates for their pitch category and all of which avoided extra-base hits exceptionally well.

The unexpected nature of seam position-based movement may be a source for Ashby’s persistent command issues, as this is much less repeatable and controllable than spinning the baseball, but the movement he generates is above-average because of seam-shifted wake.

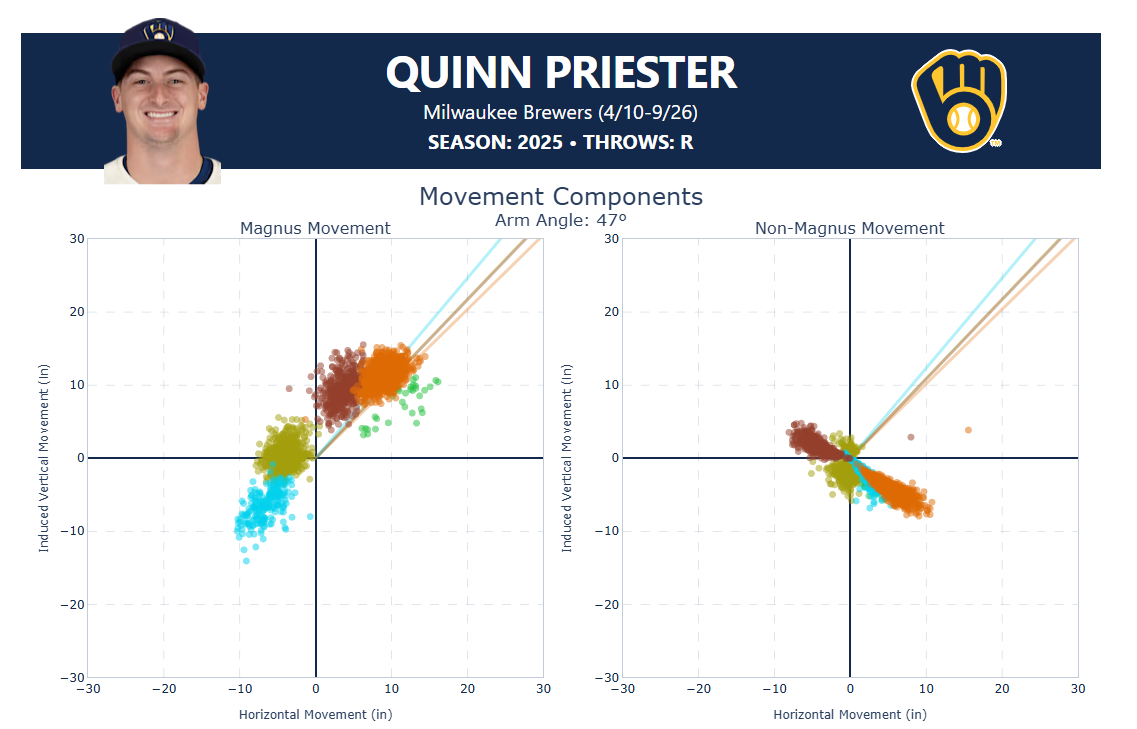

One other Brewers pitcher with even more extreme seam-shifted wake control is Quinn Priester. Before coming to the Brewers, the scouting report on Priester was that he had a fringy sinker that had never really performed, and the total movement he generated was nothing to write home about. However, when you factor in his arm angle, spin rate and seam-shifted wake factors, his profile jumps off the page—particularly thanks to his cutter and his sinker.

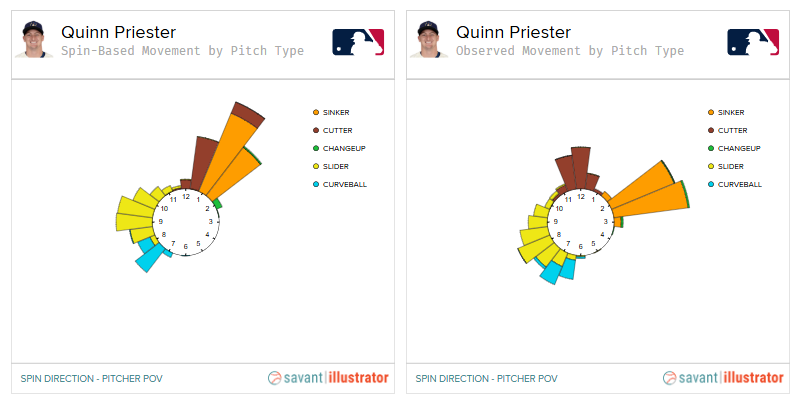

Like Ashby, Priester is getting 6-8 inches of vertical drop on his sinker, relative to what the hitter expects, as well as almost 10 inches of horizontal break. His cutter is moving the other way, riding and breaking in on left-handed hitters with a spin direction that has some crossover with his sinker, making it difficult to differentiate the two pitches based on spin alone.

Seam-shifted wake plays up far better when the spin directions of two offerings match or mirror each other, while the non-Magnus effect takes them in different directions out of the hand. Ashby’s four-seam fastball and his slider, despite similar non-Magnus effects, would not get mistaken for each other out of the pitcher’s hand. Another, better example is how you can see with both Ashby and Priester that the changeup closely resembles their primary fastballs.

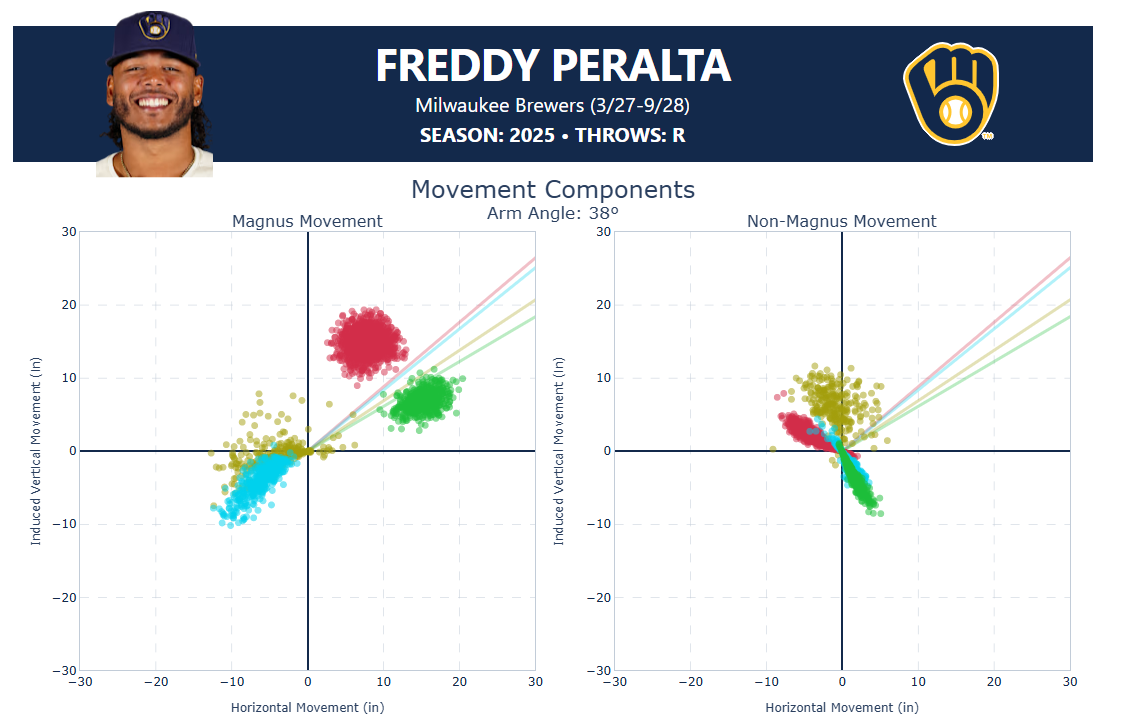

Not so with Freddy Peralta, whose changeup spins slightly differently from his primary fastball, which makes it easier to recognize and thus lay off. One of Peralta’s biggest problems is that none of his pitches resemble his fastball in how they spin. He can get fantastic grades for his raw stuff with the fastball, but its lack of deception out of his hand means he is fighting an uphill battle with his primary offering. He fools hitters with angles and good repetition of his delivery, rather than with spin or non-spin movement.

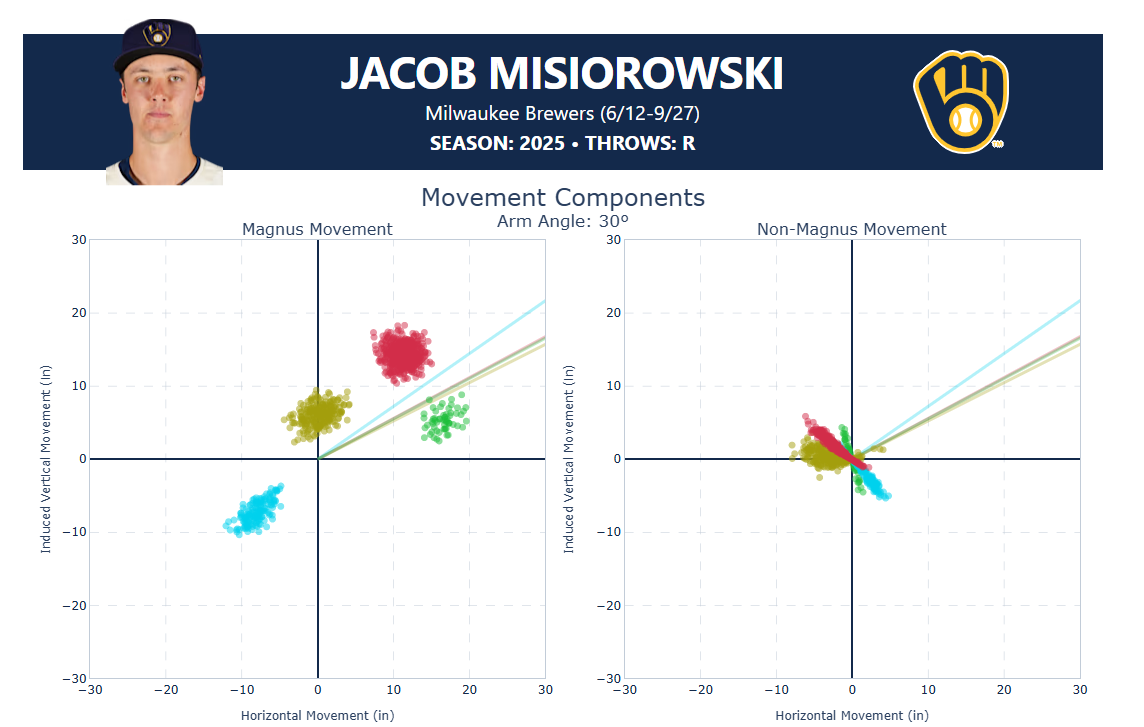

Some pitchers are very spin-oriented. Jacob Misiorowski is a prime example, generating nearly all of his movement from the spin profile. He’s heavily reliant on his raw velocity and stuff to keep hitters off-balance:

For most pitchers, though, manipulating the seams is part of generating movement that the batter can’t readily anticipate and neutralize. Seam-shifted wake has a massive impact on how a pitcher can continue to get uncomfortable swings, the more so when two pitches move differently due to seam position while having comparable spin directions. Ashby and Priester use this to devastating effect, and it’s been a major part of pitcher development programs for years. The concept isn’t new—many changeups, sinkers, cutters and some versions of the slider have relied on seam-shifted wake for decades. Now, though, we can measure it, train it, and talk about it much more readily, because technology has caught up to the craft of pitching.

Pitchers are better than ever throughout the major leagues, and it’s not just because there hasn’t been an expansion to stretch the league’s pitching staffs thinner in over 25 years. Hurlers make better use of technology, and are learning how to not only harness both spin- and seam position-based movement, but use them in concert. Better measurement and understanding of these effects has been a game-changer, and it will continue to play a major role in pitching development and instruction for years to come.