A lightning rod for controversy throughout his 13 years in the big leagues, Alex Johnson also helped the Major League Baseball Players Association flex its muscles during one of the early tests of the union.

On the field, Johnson was a line-drive machine and produced an American League batting title while becoming one of the most coveted hitters of his time.

Born Alexander Johnson on Dec. 7, 1942, in Helena, Ark., he moved with his family to Detroit as part of the Great Migration. His father took a job in an auto plant – later opening his own trucking company – and Johnson starred as a football and baseball player throughout his youth.

“Alex would have been good at football, too, because he’s so mean,” Tigers star Willie Horton, who played at Detroit’s Northwestern High School with Johnson, told the Associated Press in 1970. “In high school, his coaches were always afraid to say anything to him because they never knew how he’d respond.”

It was not an idle statement by Horton. In his 1989 autobiography “Crash”, Dick Allen claimed Johnson would aim profane language at virtually anybody he encountered.

“Why was he so underrated? Why was he traded so often? Why don’t you hear his name today?” Allen wrote. “I’ll tell you why: Because he called everybody (expletive). To Alex Johnson, baseball was a whole world of (expletive). Front office types would take it personally. But then again, maybe Alex hit a nerve.”

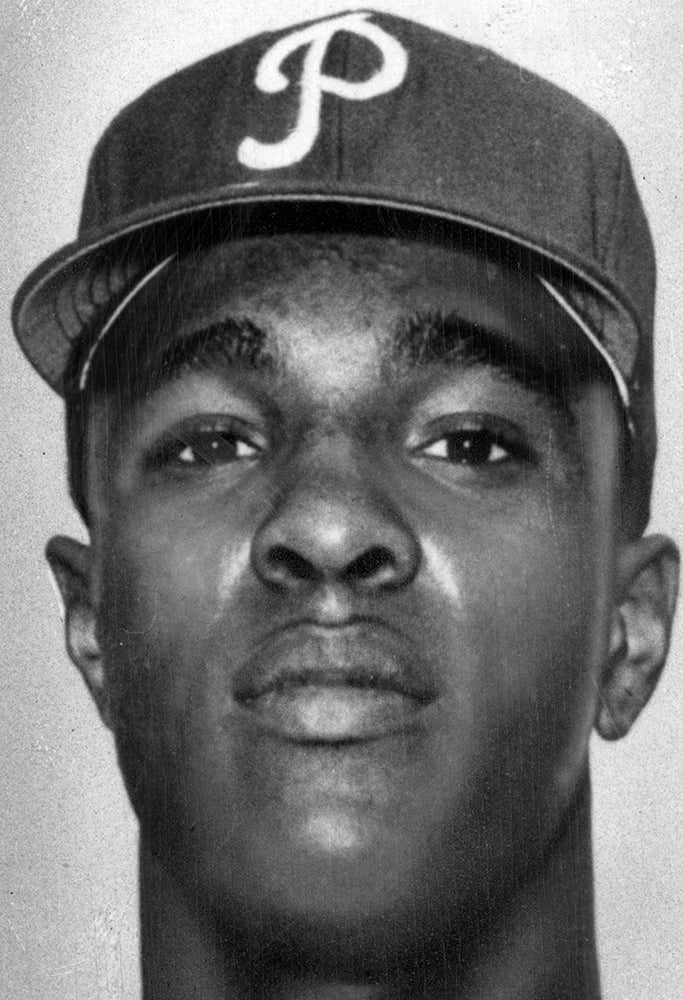

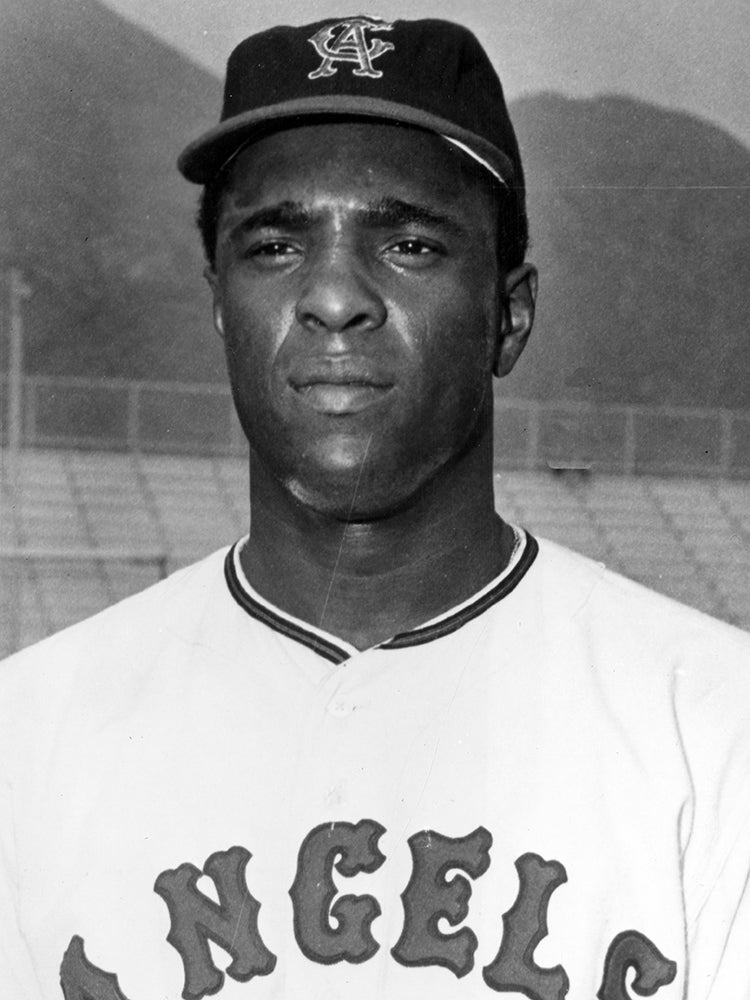

Alex Johnson batted .288 with 1,331 career hits across 13 major league seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

Johnson was an offensive lineman on the football field but turned down a scholarship to play at Michigan State and signed with the Phillies on July 11, 1961. In his first stop in pro ball in 1962, Johnson batted .313 with 16 doubles, 11 triples and five home runs in 113 games for Class D Miami.

A year later, Johnson tore apart the Class A Pioneer League at Magic Valley, hitting 35 home runs with 128 RBI and 294 total bases – all totals that led the league – while batting .329 and stealing 28 bases in 120 games.

The Pioneer League was known to favor hitters – Allen hit .317 with 21 homers and 94 RBI for Magic Valley in 1961 – but Johnson’s number caught the eye of everyone throughout baseball.

The Phillies sent Johnson to Triple-A Arkansas after he performed well in Spring Training, and Johnson hit .316 with 21 homers and 71 RBI in 90 games before the team called him up to Philadelphia in July. The Phillies were in the midst of a 92-win season powered by Allen’s Rookie of the Year campaign, and Johnson stepped right into the lineup and had three hits and two RBI in his debut game on July 25 against the Cardinals.

For the rest of the season, the right-handed hitting Johnson platooned with lefty Wes Covington in left field, often batting right behind Allen in the lineup. Johnson hit .303 with four homers and 18 RBI in 43 games as the Phillies faltered down the stretch and were passed by the Cardinals.

But heading into the 1965 season, many envisioned Allen and Johnson as a duo that would power the Phillies for the next decade. Johnson’s muscular physique quickly earned him the nickname “The Bull” – a moniker that would one day be associated with another Phillies slugger: Greg Luzinski.

Johnson played winter ball in Puerto Rico following the 1964 season and – as he had everywhere else – hit well, putting together a 19-game hitting streak. Phillies manager Gene Mauch returned to his Covington/Johnson platoon in left field in 1965, but Johnson and Mauch began to clash over the player’s perceived lack of hustle.

On May 17 vs. the Cardinals, Johnson went 3-for-4 to raise his batting average to .353. But Mauch fined him $100 for not running out a popup to right field that Mauch believed should have resulted in a double rather than a single.

“I can think of several reasons why I don’t expect him ever to go that slow again,” Mauch told the Philadelphia Daily News.

Johnson, meanwhile, disputed the notion that he did not hustle.

“You’ll never see me loaf on a play that means something,” Johnson told the Daily News. “I didn’t run hard on that one, but all I could have gotten was one base anyway.”

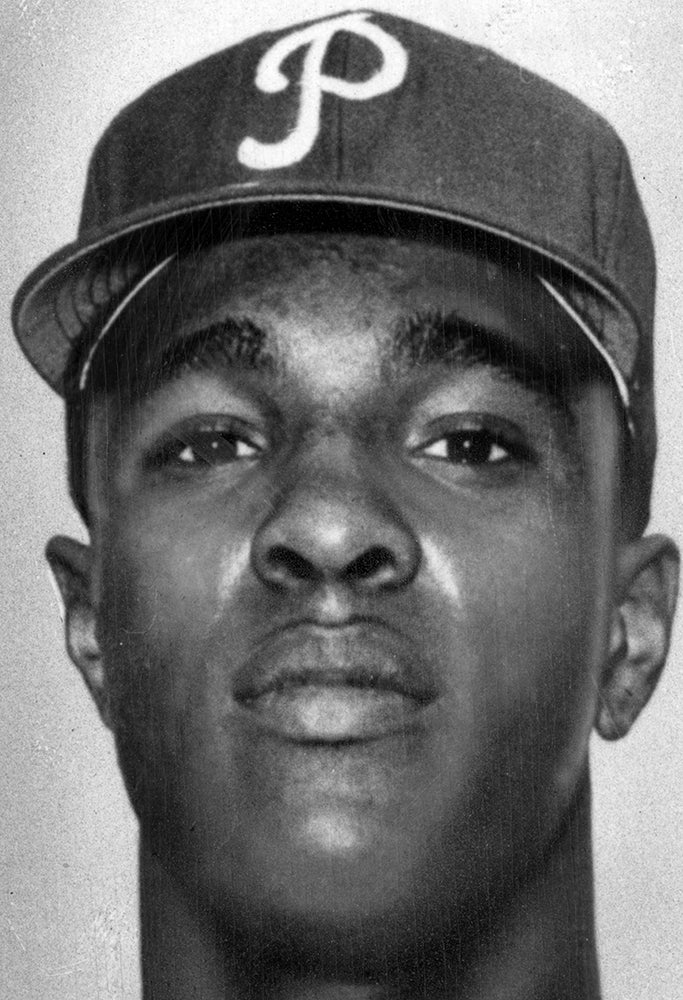

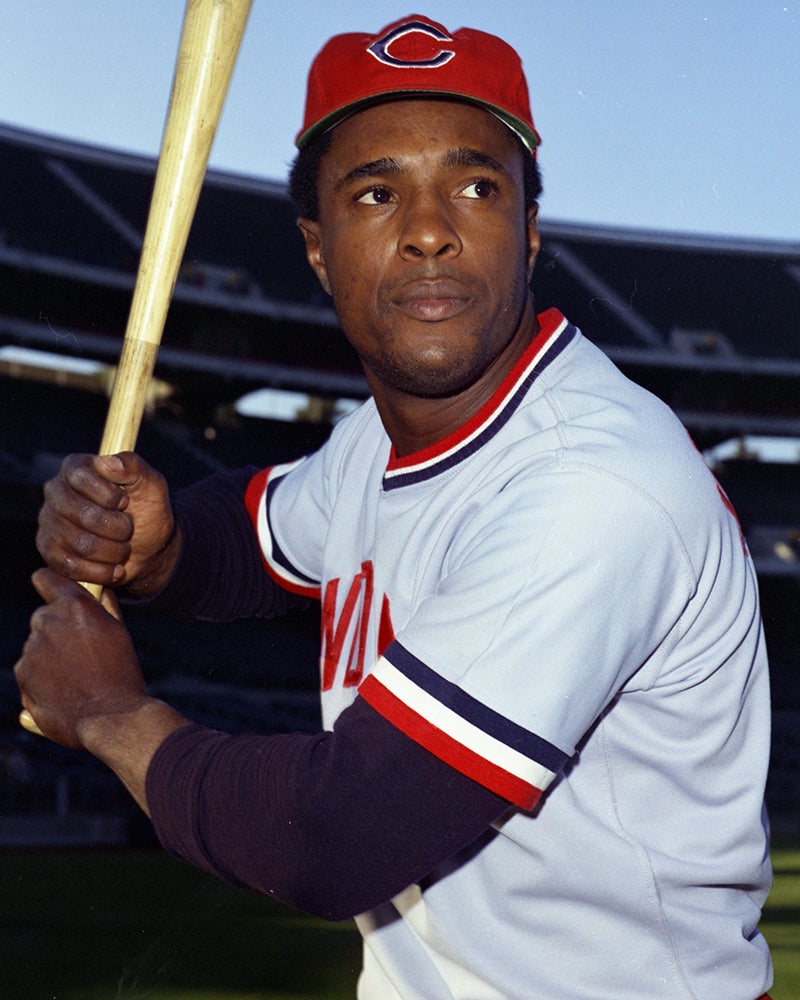

Dick Allen won the 1964 National League Rookie of the Year and shared the Philadelphia lineup with Alex Johnson that season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

Johnson hit .294 with eight home runs and 28 RBI in 97 games that year and was widely regarded as a future star. With that in mind, the Cardinals were willing to part with All-Stars Dick Groat and Bill White – along with Bob Uecker – in an Oct. 27 trade that brought Johnson, Pat Corrales and Art Mahaffey to St. Louis.

“Johnson gives us one of the fastest outfields in baseball,” Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the AP, envisioning Johnson joining Lou Brock and Curt Flood in his lineup.

The Phillies, meanwhile, would not parlay the Johnson/Allen combination to fruition – and would not compete for another postseason berth until the 1970s.

“They said Alex Johnson was surly,” Allen wrote in his autobiography. “But when Alex played with the Phillies, he would come to my house all the time and play with my kids. Alex just wanted to be left alone to play baseball.”

By 1966, Johnson’s brother, Ron, was a sophomore on the University of Michigan’s football team. Almost six years younger than Alex, Ron became a star at Michigan, rushing for 1,391 yards and 19 touchdowns in 1968 – becoming the first Black team captain in Michigan history that year – while finishing sixth in the Heisman Trophy voting and setting a then-NCAA record with 347 yards rushing against Wisconsin.

Drafted in the first round by the Cleveland Browns in 1969, Johnson backed up Leroy Kelly for a season before being traded to the New York Giants, where he became the first player in team history to rush for 1,000 yards in a season in 1970.

Alex Johnson, meanwhile, slogged through two years with the Cardinals as his brother became a star at Michigan.

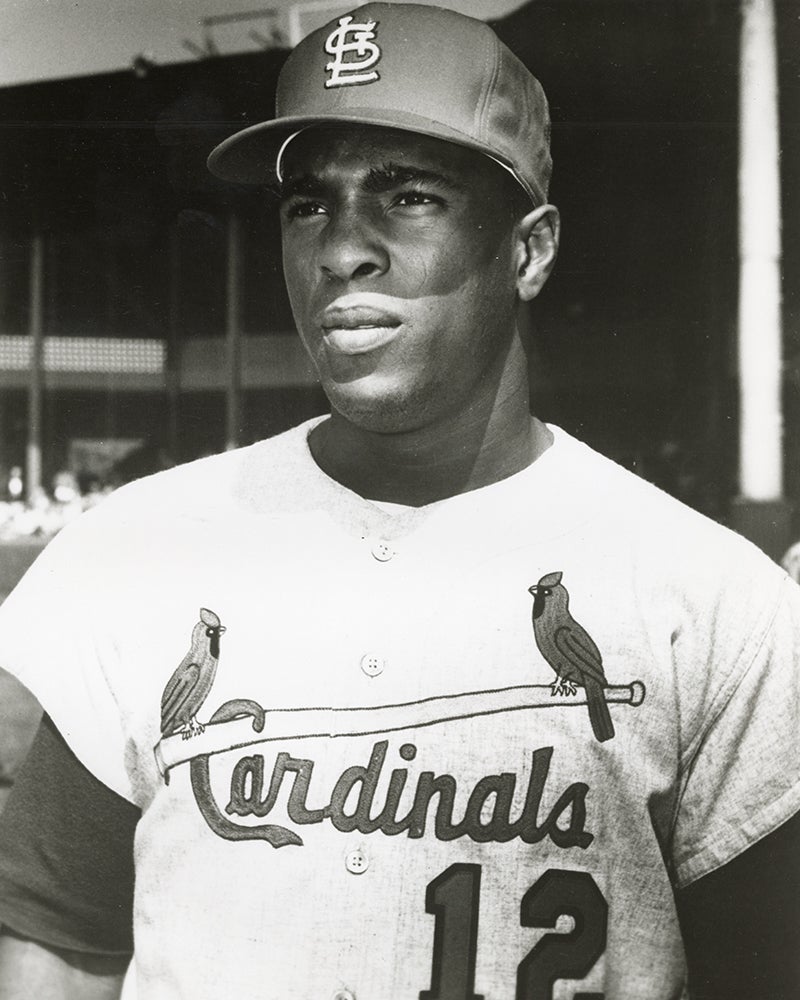

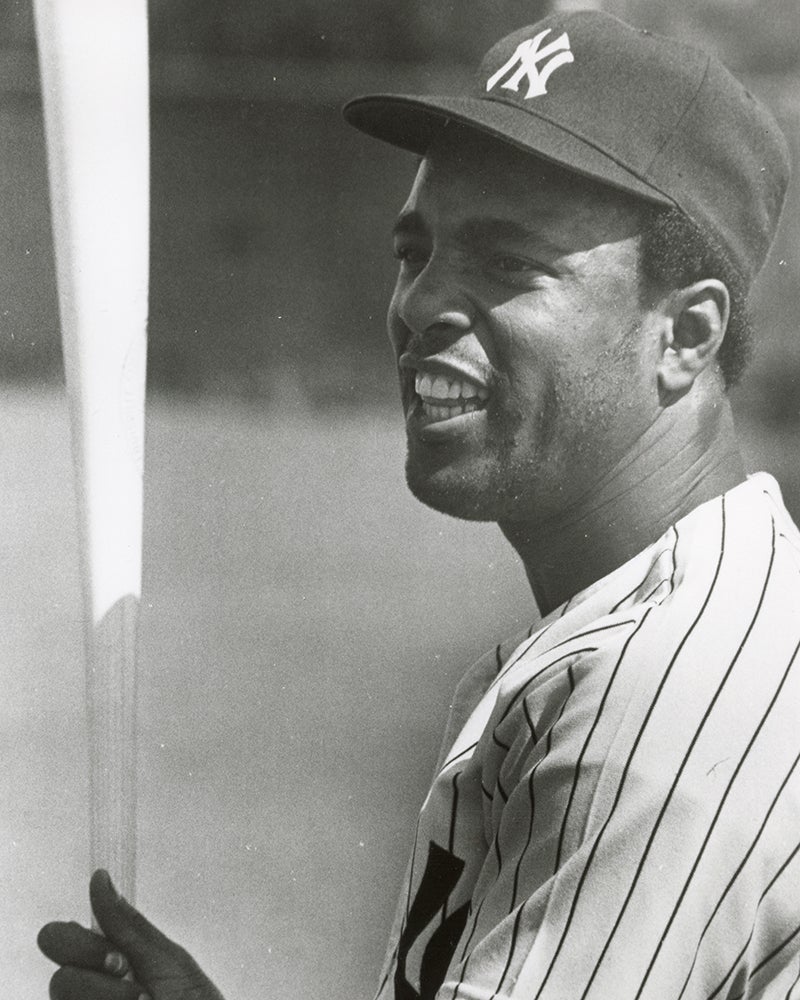

Alex Johnson appeared in 81 games in 1967 as the St. Louis Cardinals captured the National League pennant and went on to win the World Series. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

In 1966, the Cardinals moved Brock to right field to get Johnson into the lineup in left. But the plan failed when Johnson began the season in a slump. After seeing his average drop to .195 after a three-strikeout game against the Giants on May 6, Johnson was moved into a platoon role with Mike Shannon. Then on May 18, Johnson was sent to Triple-A Tulsa when Bobby Tolan was brought up to St. Louis.

Brock returned to his customary left field spot, and Johnson spent the rest of the season in Tulsa, batting .355 with 14 homers and 56 RBI in 80 games.

Johnson spent the entire 1967 season with the Cardinals, mostly in a right field platoon with Roger Maris. He hit .223 with a homer and 12 RBI in 81 games as the Cardinals won the National League pennant.

Johnson was the only position player on the Cardinals’ World Series roster who did not see action in St. Louis’ seven-game win over the Red Sox in the Fall Classic.

On Jan. 11, 1968, Johnson was traded to the Reds in a one-for-one deal for outfielder Dick Simpson.

“I didn’t like St. Louis,” Johnson told the Newspaper Enterprise Association during the 1968 season. “I had a misunderstanding with management. They wanted to change my way of hitting and I didn’t pay any attention.”

But Johnson had no such troubles in Cincinnati. In what became known as The Year of the Pitcher in 1968, Johnson hit .312 with 188 hits – both of which ranked fourth in the NL. And though he only hit two home runs, Johnson had 32 doubles, six triples, 58 RBI, 79 runs scored and 16 stolen bases in 149 games.

The Sporting News named Johnson its 1968 NL Comeback Player of the Year.

“Every time I come to bat, I improve on the last time I was at the plate,” Johnson told NEA during the 1968 season. “It’s a matter of getting in the right gear.”

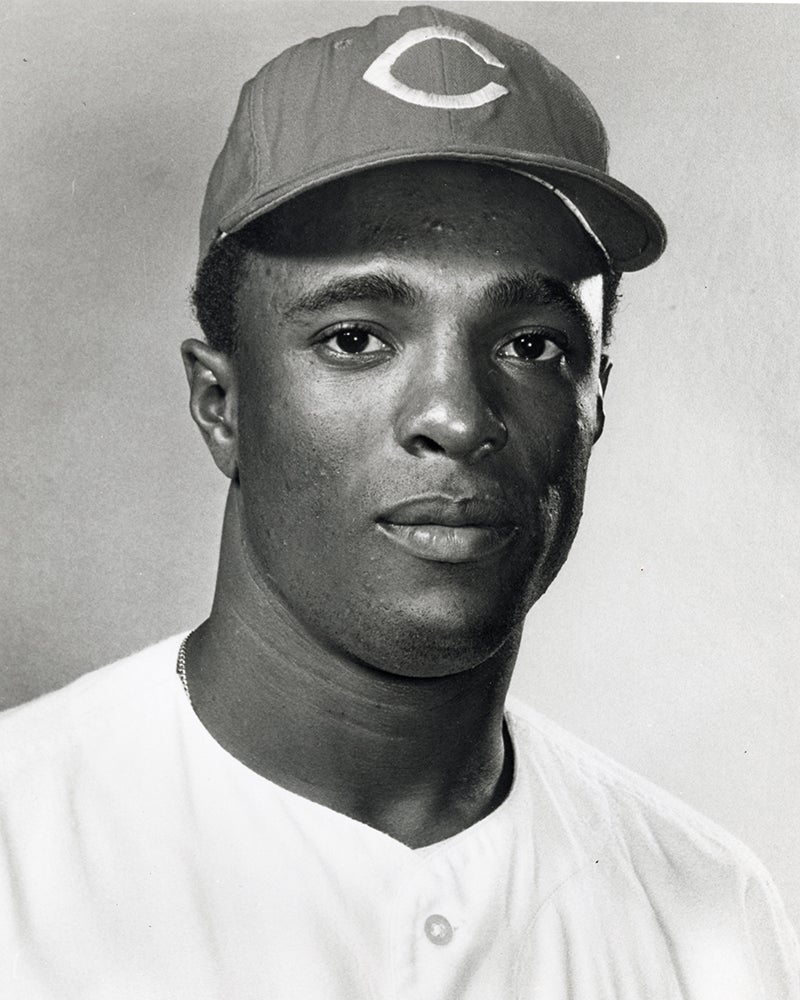

Alex Johnson produced a career-high 17 home runs and 88 runs batted in with the Reds in 1969. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

Johnson was even better for the Reds in 1969, hitting .315 with 17 homers and 88 RBI. But fielding miscues (Johnson led all MLB outfielders with 18 errors in 1969 after topping the same category with 14 errors in 1968) and a perceived lack of hustle tested the patience of Reds management.

General manager Bob Howsam decided to improve the club by dealing from his lineup depth following an 89-win season, and Johnson was sent to the Angels along with Chico Ruiz on Nov. 25, 1969, in exchange for pitchers Pedro Borbón, Vern Geishert and Jim McGlothlin.

“This is the first step in strengthening our hitting and I believe we made a fine deal,” Angels manager Lefty Phillips told the AP. “Johnson is the type of hitter we have been looking for. He will hit us 15 or more home runs and get a lot of extra base hits.”

Phillips got all that and more in 1970 as Johnson was named to his first All-Star Game. On Sept. 9, 1970, Johnson hit a ball off White Sox pitcher Billy Wynne that traveled an estimated 460 feet and landed in the center field bleachers at Comiskey Park. It was the third AL home run ever to reach those stands, with Johnson joining Hall of Famers Jimmie Foxx and Hank Greenberg on that list.

On the last day of the season on Oct. 1, Johnson entered the game against the White Sox batting .3273 while Carl Yastrzemski led the AL with a mark of .3286. But the Red Sox had finished their season on Sept. 30, and Johnson and the Angels still had one game to play.

Batting in the leadoff spot – rather than his customary cleanup position – to maximize his at-bat chances, Johnson grounded out in the first inning but followed with singles in the third and fifth innings. That brought his batting average up to .32899, and he left the game following the second hit in favor of pinch-runner Jay Johnstone – wrapping up the AL batting title.

“Somebody told me before the game it would take three hits to win (the batting title), so I was caught by surprise when they put Jay in to run for me,” Johnson told the AP. “But when I saw him come out of the dugout, I figured I must be on top.”

Alex Johnson became the first Angels player to capture the American League batting title in 1970 when he hit .329 to edge out Carl Yastrzemski for the crown. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

Johnson finished the season with 202 hits, 26 doubles, six triples, 14 home runs, 86 RBI and 17 steals. But he also led all MLB left fielders with 12 errors and – as he had in his previous stops – clashed with the manager over effort issues.

It would be only a glimpse of what was to come.

“I don’t understand Alex,” Willie Horton told the AP in 1970. “I’ve known him all my life. He doesn’t like to joke around at all. He’s all business. He wants to just do his job and leave it at that.

“He doesn’t want to bother with people. He doesn’t want people to bother him.”

Johnson signed a contract worth a reported $50,000 for 1971, and the Angels were widely expected to challenge for the AL West title. But before the regular season even began, Johnson was drawing Phillips’ ire for not hustling during exhibition contests. He was batting .277 with a homer and six RBI through April but was fined and benched repeatedly by Phillips. The fines would eventually total more than $3,750.

In June, Johnson accused teammate Chico Ruiz of pulling a gun on him in the Angels’ clubhouse. Johnson told the media he had “lost my desire to play.”

It was around this time that Phillips had told Johnson he would never play for the Angels again – but he changed his mind as the team tried to find a trade partner before the June 15 deadline. When that came and went with no deal, Phillips put Johnson back in the lineup.

“I talked to (Johnson) in ’70 and I talked to him three or four or five times this year,” Phillips told the Daily Breeze of Torrance, Calif. “I have no further plans to call him in for a talk.”

On June 24, Phillips again benched Johnson for failing to run out a ground ball. The next day, the Angels suspended him indefinitely for what Angels general manager Dick Walsh wrote was Johnson’s “failure to give your best effort.”

“I bent over backwards for the man,” Phillips told the Long Beach Independent-Press Telegram. “I said before the season we could not win without his bat so he was given every opportunity to straighten out his problems. And I – to this day – do not know what they are.”

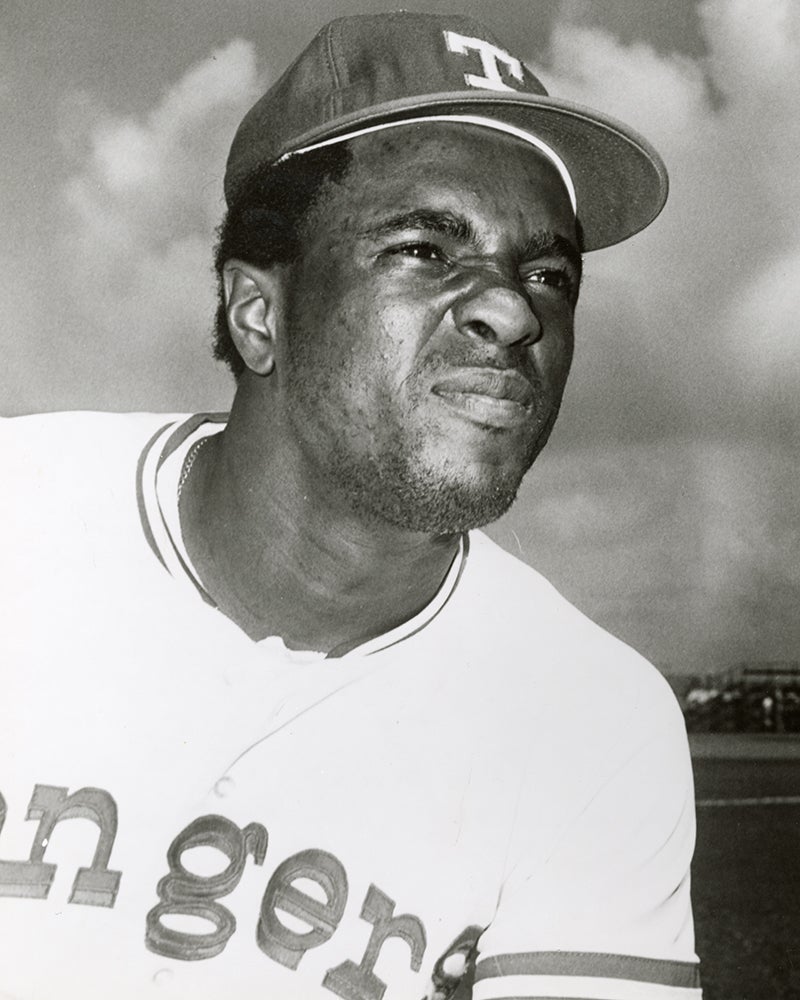

Alex Johnson found himself at the center of a landmark arbitration case following the 1971 season. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Johnson went home to Detroit after being suspended and did not play again that year, finishing with a .260 batting average, two homers and 21 RBI in 65 games. The Angels, who had won 86 games in 1970, lost 86 games in 1971.

“It has been like a nightmare,” Walsh, who was replaced following the 1971 season, told the Independent-Press Telegram. “I didn’t believe there were so many things which could go wrong.”

But Johnson’s saga did not end with the completion of the season. The Major League Baseball Players Association filed a grievance on Johnson’s behalf, asking for back pay.

“All you have now is the allegation in general terms,” union head Marvin Miller told the AP, noting that there was not “just cause” for the suspension. “All we have is the words in the letter (that informed Johnson he was being suspended). “It’s up to them to set forth what the basis of the action is.”

Miller and the union had negotiated the right to address grievances through arbitration, and the board empaneled to hear Johnson’s case was the first in baseball history. The union argued that Johnson was mentally injured and should have thus been treated like someone who had a physical injury, with treatment and paid time away from the playing field. The board ruled in Johnson’s favor, awarding him $29,000.

Meanwhile, the Angels sent Johnson and Jerry Moses to the Indians on Oct. 5, 1971, in exchange for Frank Baker, Alan Foster and Vada Pinson.

“We think that Johnson is a fine athlete and has a very good chance to come back and help the Cleveland club,” Indians general manager Gabe Paul told the AP after the trade. “He has superior talent and we are looking for superior talent.”

Playing for his fifth team in nine seasons, Johnson began the year as Cleveland’s left fielder and was hitting .328 in early May when an 8-for-75 slump dropped his batting average to .209. A heel injury slowed Johnson down even more over the summer and he finished the year batting .239 with eight homers and 37 RBI in 108 games while leading his league in errors (among left fielders) for the fifth straight season.

The advent of the designated hitter in the American League starting in 1973 extended Alex Johnson’s career, with the former outfielder making 158 appearances that year. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

On March 8, 1973, the Indians traded Johnson to the Texas Rangers for Vince Colbert and Rich Hinton. The Rangers scored just 461 runs in 154 games in 1972 and were willing to take a chance on Johnson’s bat – especially with the advent of the designated hitter in 1973.

Johnson proceeded to deliver one of his better seasons, batting .287 with 26 doubles, eight homers and 68 RBI in a career-high 158 games.

The Rangers lost 105 games in 1973 but had hired Billy Martin to be their manager at the end of the season. In 1974, Johnson spent more time in left field than at DH and was batting .291 through 114 games when his contract was sold to the Yankees on Sept. 9. New York was making a push for the AL East title but Johnson was unable to help much, batting .214 over 10 games as Baltimore overtook the Yankees to advance to the postseason.

Johnson remained with the Yankees in 1975 and was reunited with Martin in New York when Martin replaced Bill Virdon as manager in August. Martin claimed to have no issues with Johnson, but the Yankees removed Johnson from the active roster on Aug. 26 and handed him his outright release on Sept. 4. Johnson finished the year hitting .261 with a homer and 15 RBI in 52 games.

Johnson returned to his hometown to sign with the Tigers for the 1976 season but immediately was painted by the press as a bad influence on a young team. Tigers manager, Ralph Houk, however, supported his new left fielder.

“All I know is that he has done his job down here this spring,” Houk told the Detroit Free Press from the Tigers’ Spring Training home in Lakeland, Fla. “I don’t expect any trouble from him at all.”

After spending parts of two seasons in New York, Alex Johnson returned to his hometown of Detroit in 1976. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum/Major League Baseball)

Johnson played in 125 games for the Tigers that year, batting .268 with six homers and 45 RBI. But Detroit released him following the season. He spent part of 1977 in the Mexican League, hitting .321 in 54 games with the Mexico City Reds before his career came to an end.

Johnson eventually took over the trucking business from his father and spent the last half of his life back in Detroit. He passed away on Feb. 28, 2015, due to complications from prostate cancer.

Over 13 big league seasons, Johnson hit .288 with 180 doubles, 78 home runs, 525 RBI and 113 steals. The 1971 season will always be linked to his legacy, but Johnson will also go down as one of the leading hitters of an era that featured depressed offensive numbers.

And though he often battled with teammates, management and the media, Johnson was always true to himself.

“I have fun when I want to,” Johnson told the Newspaper Enterprise Association in 1968. “But the major leagues changes your character.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame