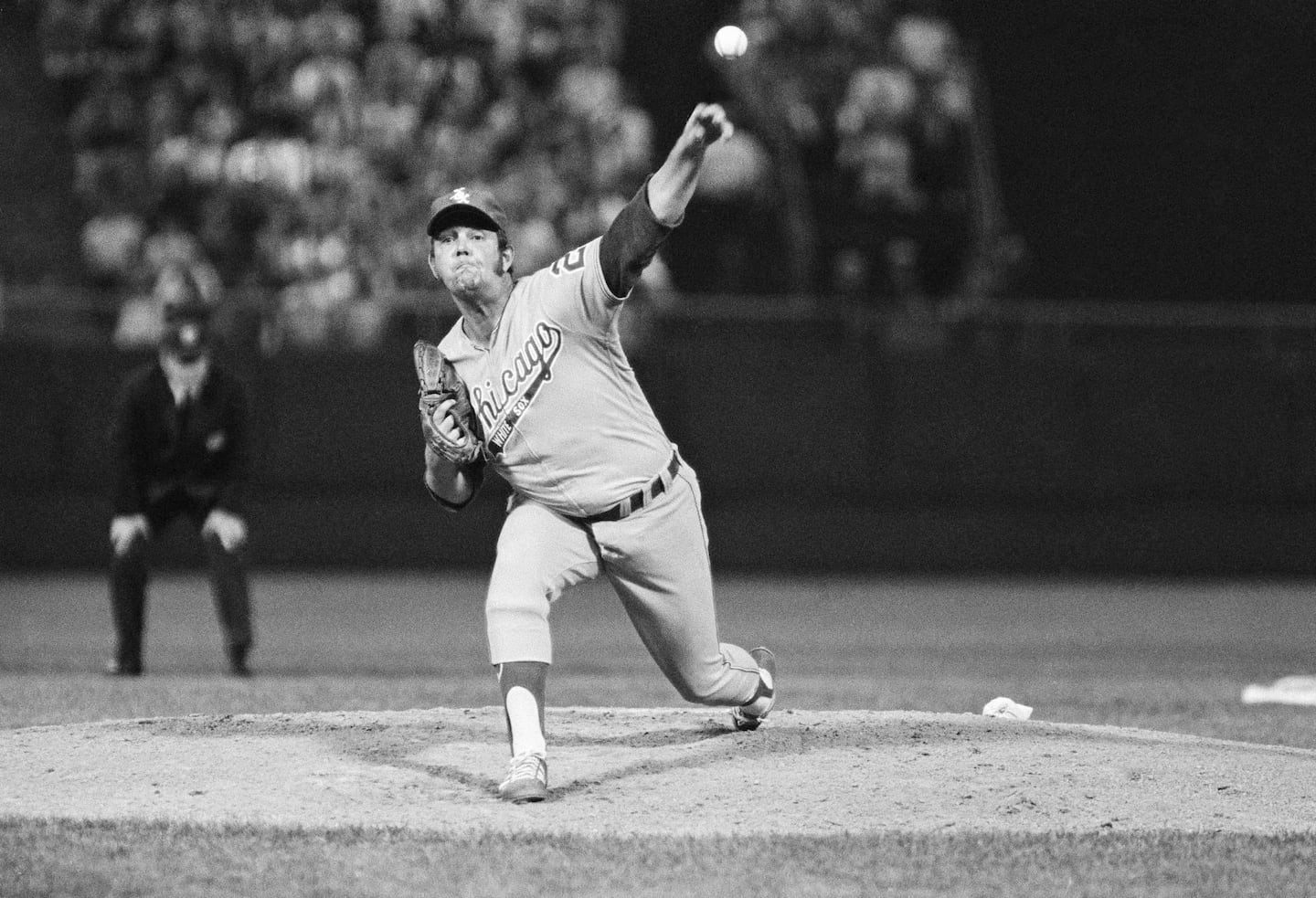

Wilbur Wood, who threw those 376-plus innings in a strike-shortened 1972 season, was anything but a hurler.

What he was: a Cambridge-born, Belmont High School-educated, Red Sox draftee turned waiver fodder pudgy master.

The subject of his mastery: the knuckleball.

Mr. Wood, who won 164 games and saved 57 in a 17-year major league career, died Saturday in Burlington. The three-time All-Star was 84.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Janet, according to The New York Times.

Mr. Wood’s numbers in 1972 for the Chicago White Sox rivaled those of pitchers in the dead-ball era of the early 1900s. His innings were the most since 1917; his 49 games started the most for a pitcher since 1908. Neither will likely be matched any time soon, perhaps never.

Get Starting Point

A guide through the most important stories of the morning, delivered Monday through Friday.

He would follow that season with another league-leading 359⅓ innings in 1973, winning 24 games, as he had in 1972. They were the second and third of four straight 20-win seasons for Mr. Wood.

Like his incongruent numbers, Mr. Wood cut a profile of anything but a stud athlete.

His White Sox manager Chuck Tanner offered a story to the Globe’s Peter Gammons in 1973 describing Mr. Wood’s everyman appearance. Tanner had invited friends to meet his team, with Mr. Wood at the end of a line of stout, young ballplayers.

“After they shook his hand, I asked them how they liked meeting the best lefthanded pitcher in baseball,” Tanner said. “They stopped cold. ‘That was Wilbur Wood?’ They thought it was . . . a janitor.”

For Mr. Wood, the crack was nothing new. “Falstaff in baseball underdress,” Gammons would describe him.

“Hell,” he told Gammons. “I’ve been fat all my life. I was a fat baby.”

Wilbur Forrester Wood was born Oct. 22, 1941, to Wilbur Sr. and Svea Wood. His father was a star athlete at Boston University, serving as captain of both the baseball and basketball teams.

Mr. Wood would also be a standout multisport athlete. He led Belmont High to the Middlesex League football championship as quarterback.

“If I had wanted to go to college, I could have gone on a hockey scholarship,” he said. “But baseball was it.”

Relying mostly on a curveball, he threw three no-hitters as a junior and led Belmont to a state title. He didn’t lose a game as a senior.

The Red Sox signed him with a $25,000 offer. He shuffled through several minor league teams, with his curveball remaining his main offering, and the knuckleball more of an afterthought.

On June 30, 1961, a little more than a year from his high school graduation, he made his Fenway Park debut, mopping up a drubbing delivered by the Cleveland Indians. Still, he was the one thrill of the game for the Fenway faithful, “a scholastic hero when scholastic heroes still were on the front pages of Boston newspapers,” as Gammons wrote.

That acclaim would not last. He would pitch a little more than 100 innings over the next three-plus seasons with the Sox, not winning one game and losing five.

“The littlesonofagun just couldn’t throw hard enough,” the Sox’ Johnny Pesky said, “but he wanted to pitch and tried his darndest.”

He was bought by the Pittsburgh Pirates near the end of the 1964 season. After two indistinguished seasons, he was traded at the end of the 1966 season to the White Sox.

The deal was made near a low point for Mr. Wood.

“I don’t think I thought of quitting too seriously then, because I was only 24,” he told the Globe in 1973. “I guess I occasionally thought about going into the plumbing and heating business with my father-in-law, but . . . I always had confidence in myself. I figured I could make it if I got to the right place.”

The right place, for Mr. Wood, would be Chicago.

There, two mentors would turn him into one of baseball’s more dominant — and peculiar — starting pitchers. One was Johnny Sain, the old Boston Braves star who would eventually become pitching coach for the White Sox.

“I guess they always said, ‘Poor Wilbur, he just doesn’t have the natural ability to pitch in the big leagues,’ ” Sain told Gammons. “What they call ‘natural ability’ is standing 6-[foot]-4 and being able to throw a ball 100 miles per hour. Wilbur didn’t have the ability. Tools. Well, it turns out he has as much God-given ability as any man I’ve seen.”

He had that knuckeball, sure, Sain said. But he had something more important.

“He has the greatest psychological makeup I’ve ever seen,” Sain said. “Nothing ever bothers him; he’s the same, win or lose. And throwing that pitch requires the nature of a master surgeon.”

The other mentor was on the pitching staff: longtime knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm. Near the end of his Hall of Fame career, Wilhelm took Mr. Wood under his soft-tossing wing.

He encouraged him to throw the knuckler more overhand, rather than with a three-quarters delivery, from which Mr. Wood struggled to control the pitch. And he offered something less tangible but equally important: Believe in it.

“You either throw the knuckleball all of the time or not at all. It’s not an extra pitch,” Wilhelm said he told Mr. Wood, according to the Boston Herald.

Mr. Wood (right) and his mentor, Hoyt Wilhelm, offered their grips on their favorite pitch, July 20, 1968, in Chicago.Anonymous/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Mr. Wood (right) and his mentor, Hoyt Wilhelm, offered their grips on their favorite pitch, July 20, 1968, in Chicago.Anonymous/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The change paid dividends almost immediately.

Mr. Wood would become the workhorse of the White Sox bullpen, leading the league in games in 1968, 1969, and 1970, and earning 52 saves over those seasons.

In 1971, he became a starting pitcher. He won 22 games that year, with a microscopic 1.91 ERA. He finished third in the voting for the AL Cy Young Award, which went to the A’s Vida Blue. The next year, he finished second to Cleveland’s Gaylord Perry.

Few matched his win totals, even for a very average Chicago team.

“I think maybe there was some stigma to the pitch,” he said. “I guess I had to convince people a knuckleball win is as good as a fastball win.”

In 1973, he started the team’s opening game. Because the White Sox then had four days off, he started the second game too, then came back to start Game 5 as well.

In July of that season, he started the first game of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. After pitching poorly and being yanked in the first inning, he volunteered and started the second as well.

Mr. Wood was OK with the workload.

“I’d much rather start on two days’ rest than sit on the darn bench for a week,” he told The New York Times in 1973.

Besides his wife, Janet, whom he married in 1991, he leaves three children from a previous marriage, Wendy Wood-Yang, Derron, and Christen Wood Dolloff.

Even in his All-Star years, Mr. Wood would return to his roots in the Boston area, working as a plumber and seeking out times to go fishing.

He told Gammons about talking baseball with an old pal, Bob Locker of the Cubs. But the conversation was cut short when it shifted away from the 60-feet, 6 inches from the rubber to home plate.

“He wants to know what bobber I use,” Mr. Wood said. “I told him, ‘Hell, I’ll talk pitching, but I ain’t giving any fishing secrets away.’ ”

Mr. Wood (left) joined other legendary knuckleballers Phil Niekro, Tim Wakefield, and Charlie Hough during a ceremony announcing the premiere of the documentary film “Knuckleball!” at Boston City Hall in September of 2012. Charles Krupa

Mr. Wood (left) joined other legendary knuckleballers Phil Niekro, Tim Wakefield, and Charlie Hough during a ceremony announcing the premiere of the documentary film “Knuckleball!” at Boston City Hall in September of 2012. Charles Krupa

Material from The New York Times was included in this obituary.

Michael Bailey can be reached at michael.bailey@globe.com.