Brandon Sproat has been a big name on prospect lists since his entry into pro ball, using a fastball that can touch triple digits and a diverse mix of secondaries to provide adequate strikeouts and limit hard contact. In some ways, last year didn’t go to plan, as he had an unsightly 5.95 ERA in late June. At that point, he had 43 strikeouts and 32 walks in 62 innings pitched on the season. From that date on, however, he began to tweak his arsenal, with tremendous results. He dominated hitters, with 70 strikeouts and just 21 walks in his next 59 innings to post a sparkling 2,44 ERA.

How Did Sproat Address His Platoon Problems?

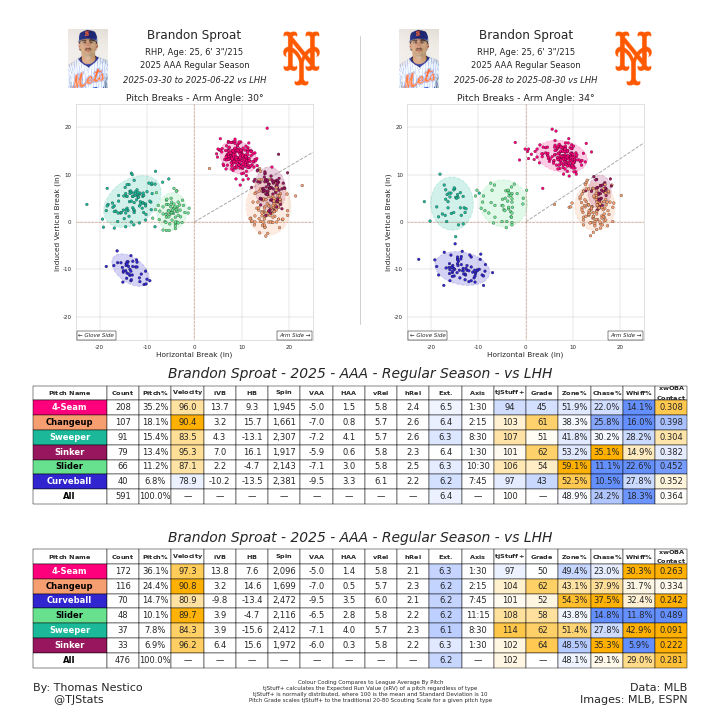

Sproat’s main problem was how he handled left-handed batters. His sinker and sweeper are somewhat neutralized by opposite-handed hitters, so he had to do some problem-solving.

First of all, the shape on his four-seamer changed, targeting less horizontal break and getting greater separation from his sinker on the rare occasions when he used the latter to lefties. This also had the added benefit of allowing him to cramp left-handers up and in, before dialling in the changeup off that pitch.

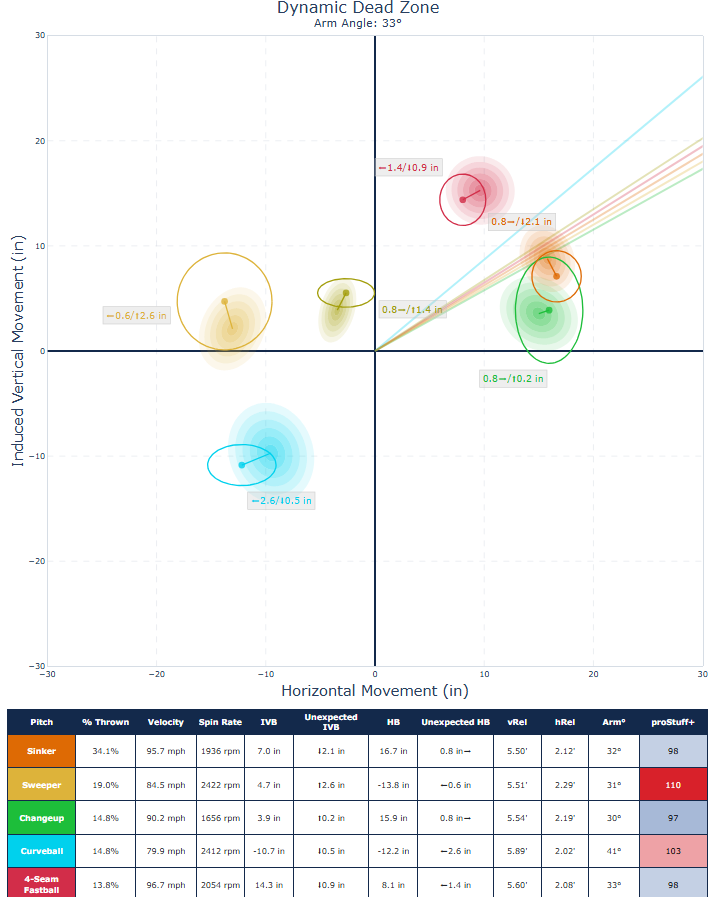

Pitch profiler’s dynamic dead zone chart shows the difference in expected movement (based on pitch type and the pitcher’s arm slot) and actual movement of a pitch. That fastball doesn’t get much ride, but it does get a couple of inches of cutting action that can make all the difference in reducing barrels. Notice, in looking at the plots from earlier, that nearly all of the pitches with significant relative cut came in that second sample, from later in the season.

He likes to work in a fairly traditional way, starting the majority of his pitches to lefties on the inner half of the plate. The four-seam fastball can work anywhere in the zone, but his command is a bit loose, leading to more pitches in the heart of the plate than would be ideal. That being said, the added “cut” helps it avoid barrels, while the changeup fades to the outer third and the curveball drops sharply to induce chases.

The changeup and four-seam are inextricably linked, each protecting the other. He only uses his primary fastball 35% of the time to left-handed hitters, meaning they can’t sit on that offering. His arsenal’s diversity is a key factor in his success, and his raw stuff is enough to transform him from a mere “kitchen sink” pitcher to a potential mid-rotation arm.

All of his pitches can be effective inside the strike zone, with unusually high in-zone rates for both his changeup and curveball compared to MLB averages. Being able to throw at least three pitches for strikes (and having a firm heater to lead that bundle) should allow Sproat to get out lefties even at the big-league level.

What About Against Right-Handers?

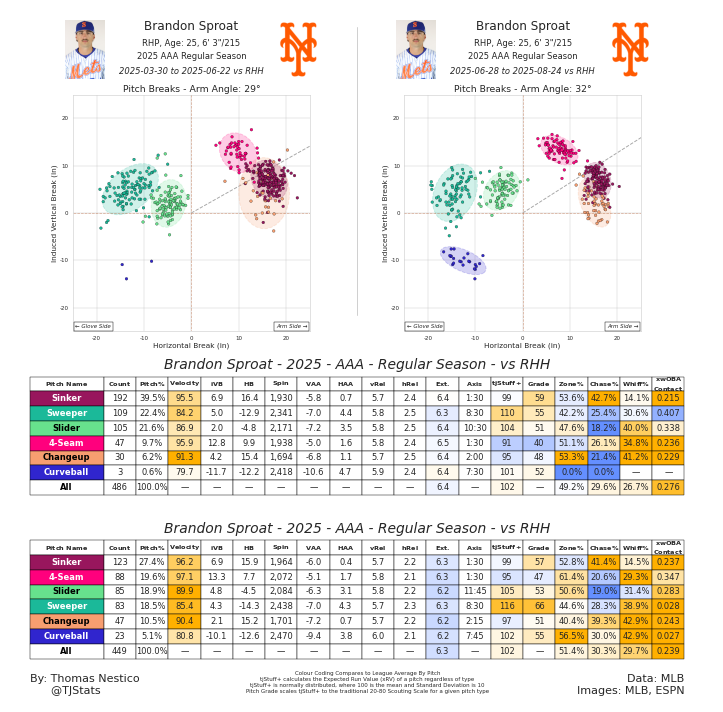

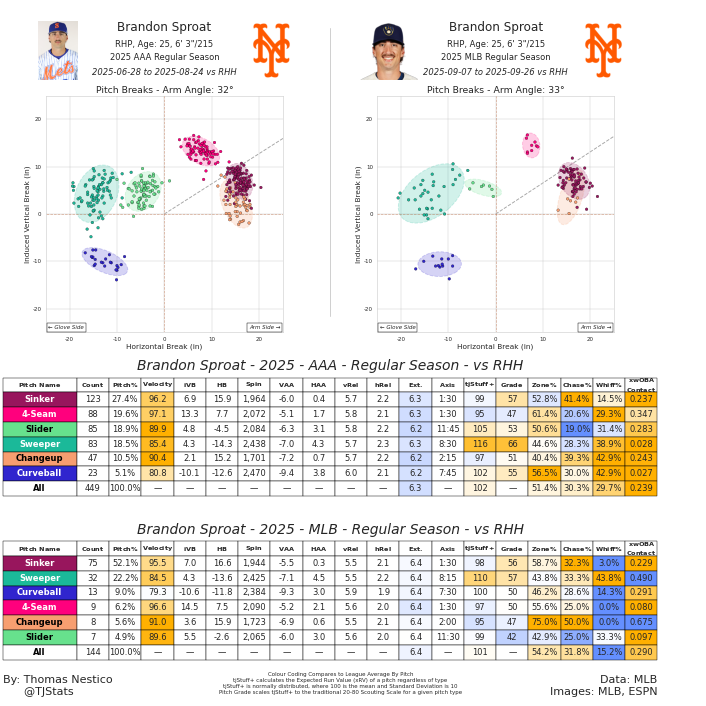

Intriguingly, Sproat diversified his arsenal more against right-handers as well, going from a sinker-heavy approach to a more balanced mix, incorporating his four-seam fastball more and overall presenting a more comprehensive pitch mix. Interestingly, although his curveball has a quite different release point (as Matt Trueblood observed here), he found some success using it more often against right-handers. One of the reasons most pitchers do better against same-handed hitters is that it’s tougher for those hitters to pick up their release point; perhaps Sproat realized that he could exploit that advantage better.

Looking at the above split, a few things jump out. First of all, there’s less cluster between his four-seamer and sinker, with the additional cutting shape I referenced earlier giving the heater separation from the sinker. Combine that with the tick upward in velocity, and you can see how, despite using the four-seam fastball more often in the second half and more regularly inside the strike zone, he maintained the effective results it showed in the first half regarding whiff rate and contact quality.

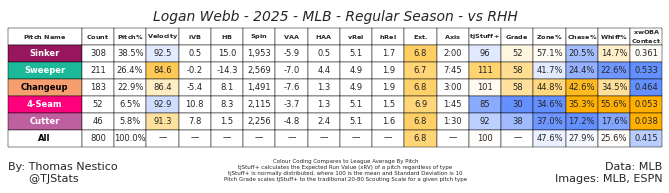

On its own, the four-seam fastball has a subpar shape with high velocity, but with his sinker keeping the batter honest, the four-seamer manages to add a wrinkle that enhances his profile. For comparison, we can look at someone like Logan Webb, who also has a subpar four-seamer.

He uses the four-seamer less than Sproat, but when played off one of the best sinkers in baseball (and please ignore the sinker grade, this offering has proven tough to measure for most Stuff+ models as there’s no one shape that makes it effective), it’s got a 55.6% whiff rate in that small sample. He used it even more to left-handers, also to good success. The main takeaways here are:

It’s a distinct shape, compared to Webb’s sinker; and

Webb gets almost 3″ less rise than Sproat, and his four-seam is overall slower and less impressive in isolation.

Sproat still has an arsenal where he throws fastballs less than 50% of the time, and it’s interesting to see him lean away from the traditional Stuff+ darlings (his sweeper and slider) in the second half for more variety, integrating the curveball just enough to keep hitters honest. A more diffuse pitch mix paid dividends.

The Big-League Picture

Upon reaching the big leagues, Sproat actually eliminated a lot of the arsenal changes he made in the minors, leaning heavily into his sinker and sweeper to both left- and right-handed hitters. Although he managed the quality of contact well (his sinker really is something), he struggled to miss bats with any regularity; that could present a problem over a larger sample size.

It will be fascinating to see how the Brewers approach Sproat—whether they isolate his best offerings like the Mets did, and in a similar vein to how they started with Quinn Priester, or lean into his variety more and try to access more of the upside in his arsenal. It will be something intriguing to follow as spring training begins in just a couple of weeks.