As any veteran of the baseball industry will tell you, the hardest tool to scout is the feel to hit. There’s so much reactivity, so fragile a balance in it, that it’s hard to gauge what a hitter can do over just a few games. It’s hard to project how a player who can dominate at one level might do at the next. It’s hard, even, to tell when a player has established a skill, and when they’re due for regression.

It was easier to scout power and arm strength and speed and defensive ability even in the days before advanced technology captured players’ movements in fine detail, but it’s even truer now. While we now know on what percentage of swings a batter makes contact and how often they chase outside the zone, every hitter has different ideal contact and chase rates, and those numbers don’t tell us about the quality of contact a player is making. We have bat speed and exit velocity and launch angle and pull rate, but those things more reliably help us measure power than hit tool. There remains a bit of magic in baseball, and it lives in the moment between the release of the pitch and the moment it reaches the plate. That’s when a batter has to make incredibly rapid, subconscious decisions, adjust their finely tuned and extraordinarily fast swing, and find the center of the ball with the barrel of their bat.

Of course, now, we also have a number for that. It’s far from perfect, but it does give us some useful information. Today, let’s consider Statcast’s Squared Up rate, and the data (both signal and noise) it provides us for the purposes of projecting two key Cubs hitters for 2026.

First, we need to define our terms. Statcast tags a batted ball as Squared Up if it leaves the bat with at least 80% of the possible exit velocity, given the speed of the swing and the incoming pitch. Physics gives us a knowable maximum exit velocity, once we have the speeds and approximate masses of bat and ball, so basically, Squared Up balls are just that: ones on which the batter successfully put lots of wood on the ball, so that they got as much out of their swing as they could.

Generally speaking, the guys you’d expect to run high Squared Up rates do so. Luis Arraez has led the league in each of the last two seasons, with roughly 40% of his swings resulting not only in contact, but in meeting the ball squarely. That it’s Arraez atop the list illustrates the drawback and the broader nature of this skill, though. Usually, guys trade some bat speed for the bat control that allows them to make such solid contact, which means that a squared-up ball can also be a relatively weakly hit or low-value one. It’s undeniably good to run a high Squared Up rate, but that skill tends to belong to slow swingers, and compensates (with varying degrees of success) for a dearth of power.

Specifically, the Cubs have two players for whom squaring the ball up is vital—whose games hinge on doing it consistently. Nico Hoerner is one of the best sheer contact hitters in baseball, but if he were prone to mishitting the ball, that wouldn’t make him a good player. With new metrics, we can see more clearly than ever that he’s an elite pure hitter, because he squared the ball up on roughly a third of his swings last year, ranking very near the top of the league.

Hoerner lacks power, because his bat speed is well below average and he doesn’t have an approach that lends itself well to pulling the ball in the air. As last year progressed, though, he proved that he can hit the ball squarely with enough consistency to be a plus-plus hitter, even without either a high walk rate or average pop. Alex Bregman brings even more to the party. He uses an extremely patient approach to inform and augment his own sky-high Squared Up rate, and his swing is geared to lift the ball to the pull field. He, too, has subpar bat speed, a concern I noted rather dourly earlier this winter. However, he makes some of the most efficient contact in baseball—even topping Hoerner.

Because of the things they don’t do well, Hoerner and Bregman have to show an elite feel for hitting. Happily, both of them do. The question is: Will that skill stick?

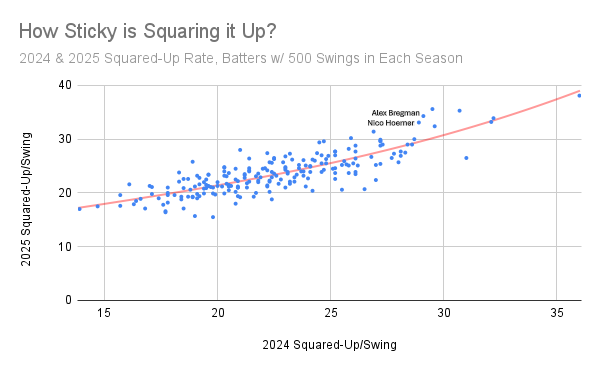

To answer it (in part), I took all 211 hitters who had at least 500 swings in both 2024 and 2025, and compared the percentages of those swings that resulted in Squared Up balls in play for each player from year to year. Here’s the resulting chart.

The R² of this plot is 0.685, which implies a very strong correlation from year to year. In other words, for the limited data we have so far, squaring the ball up is an extremely sticky skill. We might well find that it gets less neat and tidy over time, and with more seasons of data, we could do a more robust study of aging curves, but intriguingly, this population of players got better, as a group, from 2024 to 2025. Their Squared Up rate went from an average of 22.5% to 23.6%.

Bat speed tends to deteriorate as a player ages, so one explanation for the increase in squaring the ball up is hitters consciously trading the bat speed they can’t hold onto for better bat control. It’s probably more complicated than that. There’s something to be said for the theory that the proliferation of these numbers in clubhouses and hitters’ meetings has helped players train better for efficient contact, but it’s also probably more complicated than that. All we can say for sure, at this moment, is that how you did last year does a fine job of predicting how you’ll do this year, when it comes to squaring the ball up. That sounds like very good news for Bregman and Hoerner, and it probably is.

However, there’s another wrinkle we need to consider. Go back to the chart above, and notice that Bregman and Hoerner are further from the trend line than most of the rest of the league. They each improved significantly at meeting the ball squarely in 2025, even though they were above average even before making that leap. Hoerner will be 29 this year; Bregman will be 32. Most of the time, when hitters past the age of 26 or so go from good to elite at something, they’re due for regression. That invites the real concern that they’ll each come back to Earth in 2026, and square the ball up less often.

This is why, for instance, all the advanced projection systems (PECOTA: .289; ZiPS: .293; Steamer: .304) expect Hoerner to run a lower BABIP than his career mark of .307, let alone the .313 he put up in his stellar 2025 campaign. It’s hard to call anything about this luck, because we’re so far down to the process aspect of hitting, studying how well a hitter’s hand-eye coordination manages the task of getting lumber on leather. Still, there’s variance and entropy at work, here. Pitchers will make adjustments, to both Hoerner and Bregman. It won’t be easy for either to sustain the level of success they’ve had at squaring up the ball lately.

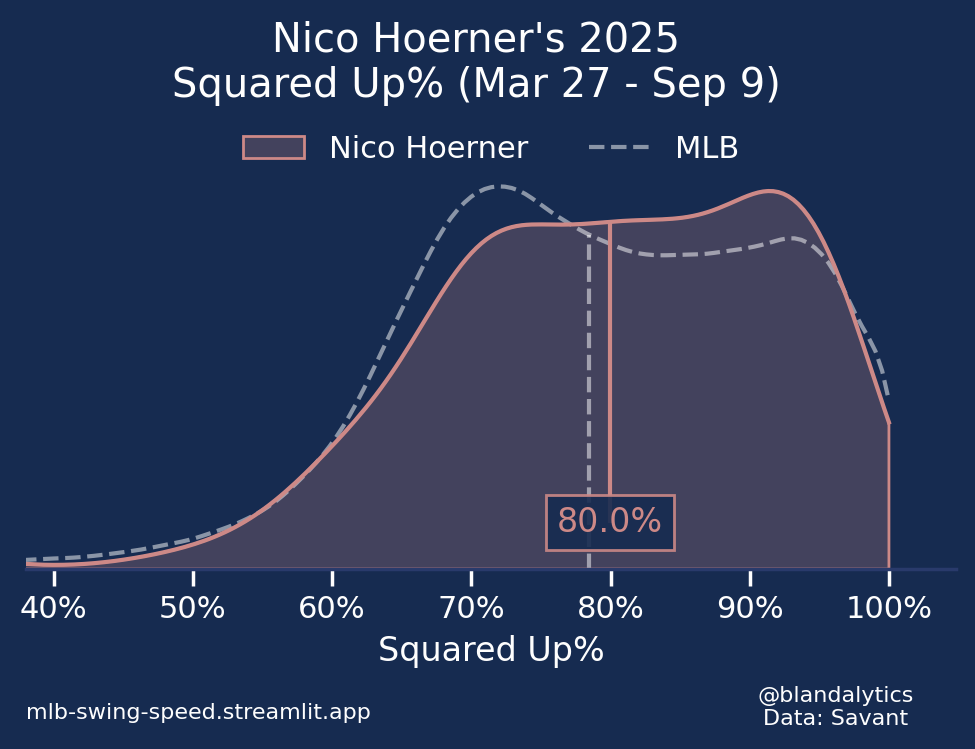

To figure out which is more likely to retain their skills and have a successful 2026, we can approach this in a slightly different, better way. Kyle Bland of PitcherList created an app to display bat-tracking data back in 2024, and one of its features is a more continuous measurement of squared-up contact. Rather than creating a binary and tagging a ball as either squared up or not, his model tracks the specific percentage of the maximum possible exit velocity on each batted ball. Here’s the distribution of Hoerner’s batted balls by Squared Up%, for (most of) 2025.

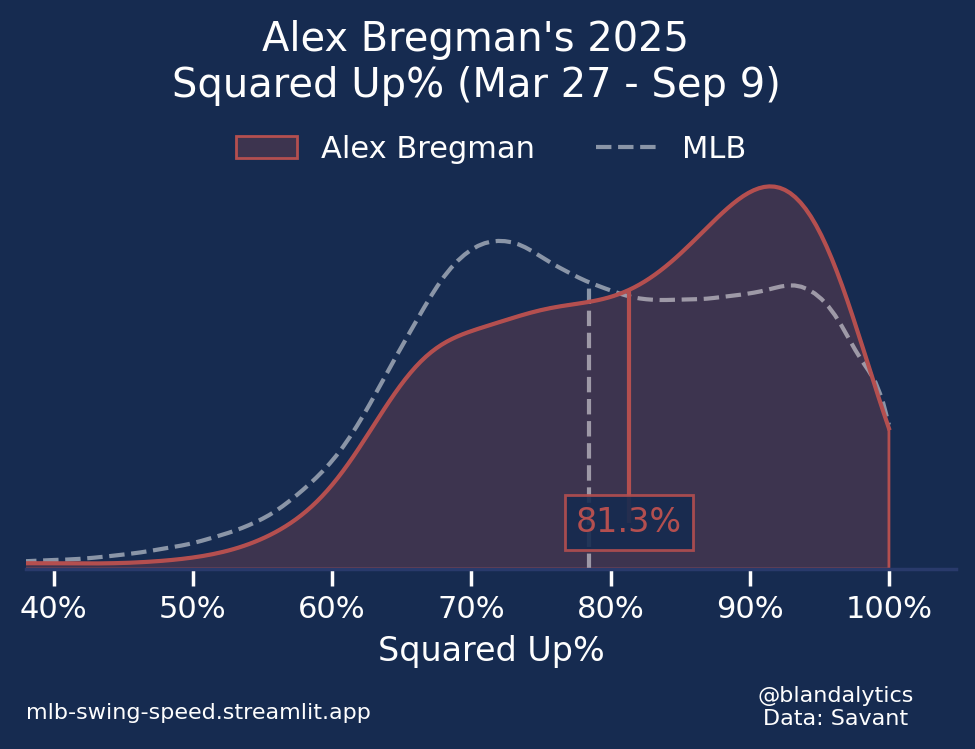

He’s very, very good at hitting the ball squarely, and though he rarely gets all of a pitch—he’s just ok at generating contact efficiency north of about 92%—he also rarely mishits one at all. That’s a steady hitter. Bregman’s distribution is a bit more impressive, and almost laughable:

Bregman creates a whole lot of extremely efficient contact, though he’s also considerably more likely to whiff altogether (Squared Up%: 0) than is Hoerner. Which of these two is more likely to sustain their success at squaring it up, going forward?

Hoerner, being younger, gets a certain edge. Bregman’s swing is flatter, too, and flat swings generally lead to lower Squared Up rates. However, Bregman has honed his approach so well that he’s locked in to swing only at pitches he can consistently square up. Hoerner’s is a more expansive, aggressive, all-fields approach. We should also consider what happens if each player’s suite of swings gets a tiny bit less efficient, across the board. For Hoerner, he would slosh back much closer to league average. Bregman might see his strikeout rate spike a bit, because his swings getting less efficient would mean getting out of the top end of the league in overall contact rate, but he has that big bulge in the upper 80s and 90s for Squared Up% that would come down only to the low and middle 80s. In other words, he can stay efficient with his contact even if he loses some efficiency in his swing. Hoerner lacks that luxury.

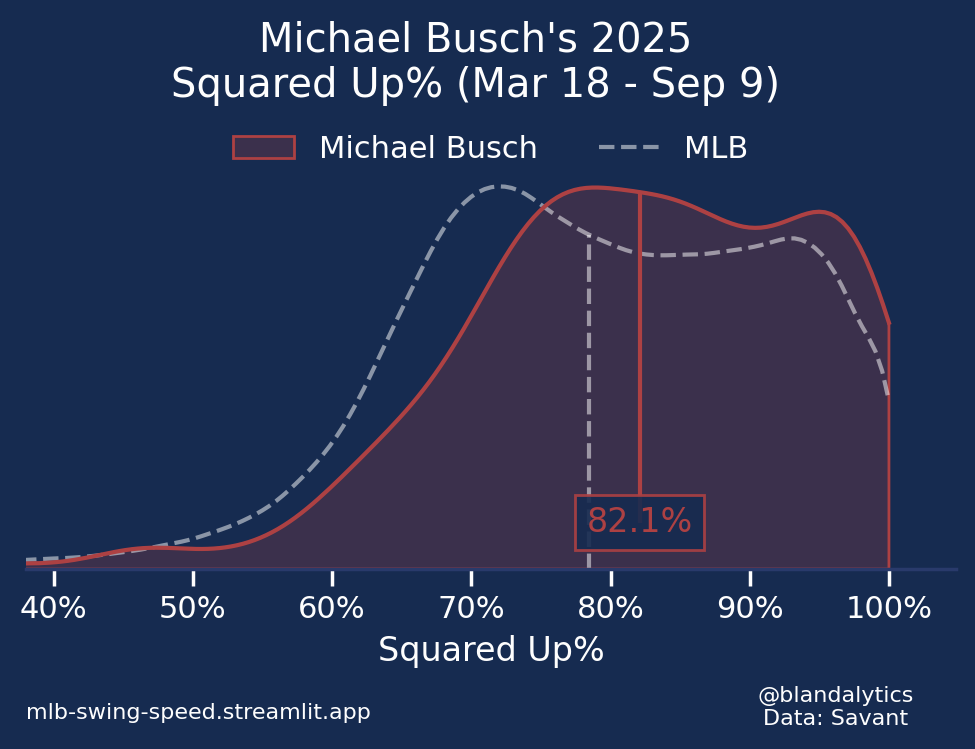

Bregman is a safer bet than Hoerner to hold onto this skill, but each of them did something at an elite level last year that tends to stay good once a hitter has shown they can do it. That makes it worth mentioning one more player of whom the same things are true: Michael Busch. He was much more prone to sub-80% contact efficiency than were Hoerner and Bregman last year, but he was also better than they were at getting the crosshairs on a ball and achieving perfect (or virtually perfect) Squared Up-itude. This is a slugger with great feel for contact, in profile. Note the dearth of swings that generated less than 70% contact efficiency. If he was going to be that wrong, he stayed committed to his ‘A’ swing and came up empty. When he got one right, though, he gave himself a chance to get it especially right.

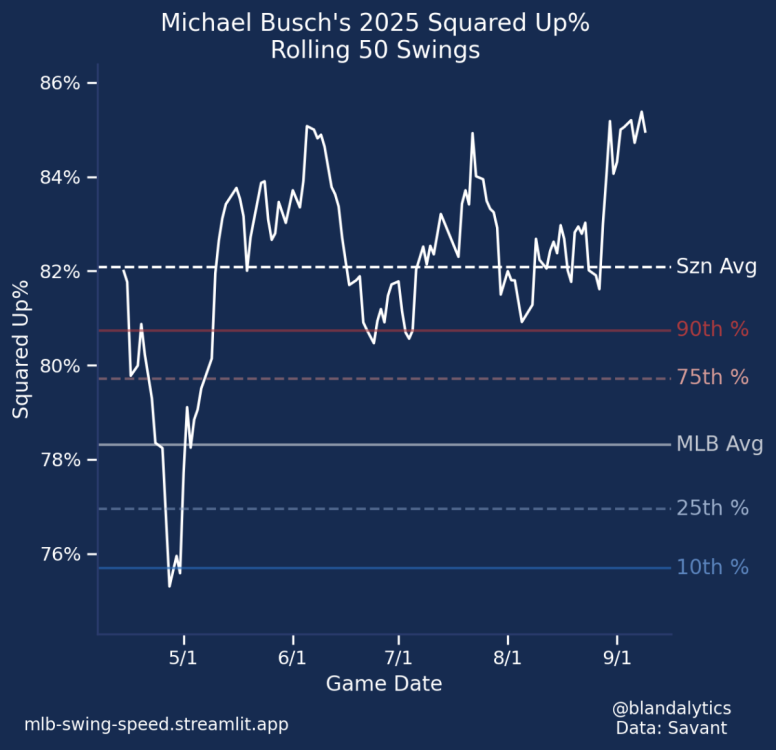

Bland’s app also tracks rolling Squared Up% for hitters throughout the season, and Busch’s timeline tells a great story. In early May, he simply locked in on the ball, and never ceased to be so.

Like Hoerner and Bregman, Busch lacks elite bat speed, especially for a player who needs to produce more power than either of the others do. However, from May 15 through the end of the season, he slugged .539, and then he went on an October power binge, to boot. Much of that can be attributed to his ability to square the ball up, and he’s another good candidate to do so again in 2026.

We still have a lot to learn about hitting, but the data are making it a bit easier to say some things with confidence. If nothing else, these numbers prove that Hoerner, Busch and Bregman have plus hit tools, albeit in ways unique to each of them. They’re the anchors of the Cubs lineup for the coming season, and by the end of the year, we’ll know even more about how each of them do it—and therefore, more about how the thing is done by everyone.