It may not always feel like it outside, but spring training is coming soon. We’re just a few days away from pitchers and catchers officially reporting to the Cubs’ complex in Mesa, Ariz., and we’re less than two months from regular-season Chicago Cubs baseball.

Between now and then, we will see lots of predictions and guesswork offered up. Who’s going to lead off? Who’s going to make the Cubs bullpen? Will they run a true six-man rotation when Justin Steele returns? I have no answers to those questions today, but I can offer a prediction I feel is a stone-cold lock: Ian Happ is going to have another good season—and, as a bonus prediction, Cubs fans online will attempt to skewer the guy, anyway.

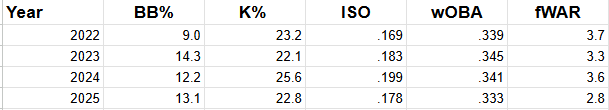

My faith in Happ lies, first and foremost, in the data; the man is incredibly consistent. For Happ’s career, he sports a 116 wRC+. Last year, Happ finished with a 116 wRC+. Between 2022 (an important line of demarcation for him, something I’ll explore later) and 2025, Happ’s best season based on wRC+ was a 122, and his lowest was a 116; he’s basically the same guy year after year. Look, below, at a chart comparing major data points over those years. There are a few data points that stand out as slightly different (e.g., the strikeout rate in 2024) but you’re mostly splitting hairs at that stage.

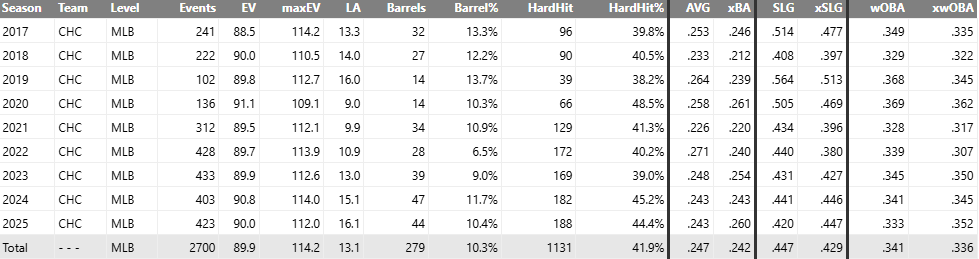

If you’re worried that Happ’s 2025 being a sign of things to come, I have some good news; he had, maybe, his best season ever, when we consider batted-ball data instead of simple results. The Cubs’ left fielder posted the second-best expected wOBA of his career last year, .020 higher than his actual wOBA, suggesting that his slight step backward in 2025 was due largely to some bad luck, tough Wrigley Field park effects, and/or the deadened baseball. This isn’t a situation where you’d have expected him to under-perform his xwOBA, either. For example, players who don’t pull the ball a lot can sometimes hide behind inflated expected data, because expected data doesn’t take into account where you hit the ball and pulling the ball produces better numbers. Happ posted some of his highest pull rates of his career last year, though, so that’s not the problem.

The oft-maligned outfielder wasn’t always this consistent. He posted a 106 wRC+ and a 105 wRC+ in two of his first five seasons. Famously, he was demoted to Iowa for much of the 2019 season due to his issues at the plate, and his 2021 season (105 wRC+) was a follow-up to a 132 wRC+ posted in 2020. Part of the reason for this was that that version of Happ struck out a lot more than he does today. The 2022 campaign was an important year for Happ, as he worked on limiting his strikeout rate and unlocked this more consistent version of himself.

Some fans charge Happ with being streaky within seasons, even if he looks metronomic when you glance at his baseball card. While it’s true that (for instance) Happ was much better in the second half than the first last season (101 wRC+ vs. a 139), his batted-ball data told a different story, which I wrote about in early August. But truthfully, all hitters are streaky. Everyone can get hot, and everyone can get cold. Freddie Freeman had a run last year between June 1 and July 28 (spanning nearly 200 plate appearances) in which the eventual Hall-of-Fame first baseman posted a 63 wRC+. That’s not to say that Happ is Freeman, but if it can happen to Freeman, well, it can happen to Happ, without proving the latter a flake.

What makes a hitter “streaky” to begin with, I don’t think we can truly say yet. While the improved bat-to-ball skills make Happ more consistent year-to-year, it doesn’t stabilize him from game to game. In a study done by Justin Choi of FanGraphs, he found no correlation between strikeout rate and streakiness within a season. Another FanGraphs entry, this time by Ben Clemens, dove into Michael Harris II‘s 2025 season and suggested that while hot-and-cold streaks beget each other to a degree, the reasons behind them are hard to fully parse. The reasons are probably so idiosyncratic—so tied to both the specific skills and approach of a hitter and the circumstances of any given moment—that explaining the phenomenon broadly is impossible. We can say, at least, that it’s not entirely a bad thing to be streaky. In the first article, the least consistent hitter in 2022 was another future Hall of Fame player, Mike Trout, who finished that year with a 176 wRC+.

We have to look beyond the ebbs and the flows to see the true greatness of Happ. In baseball, true talent is seen in year-to-year results. Freeman, despite his terrible two-month tumble, still posted a 139 wRC+ last year. His career line? A 141 wRC+. Happ’s true talent always shines through at the end of the year, even though it’s not quite Freemanesque. It’s why he, too, landed right on the nose of his career line.

736165a0-30ecda66-6e3ab337-csvm-diamondgcp-asset_1280x720_59_4000K.mp4

What we can take from this is simple: Happ is about as much of a lock to finish somewhere around a 115-120 wRC+ as you can find. He’s probably more of a lock than any other Cubs player to be what you expect him to be. Yes, there will be a few weeks wherein he’s red-hot and a few weeks wherein he’s ice-cold, but that’s a baseball issue, not an Ian Happ issue.

The Cubs’ starting left fielder is not going to be Cooperstown-bound at the end of his career, but he’s shockingly easy to predict as a well above-average player. Try to keep that in mind when he’s struggled for a few weeks. It’s pretty likely your tweet/skeet/reddit post (or comment right here at North Side Baseball) will eventually look pretty silly, when he inevitably ends up exactly where he always does. Don’t panic when he has a rough month, instead, know that Happ is truly a security blanket for the Cubs. There are lots of unknowns in the season ahead, but it’s nice to know that you have a player like Happ, who will eventually just be the guy you think he’ll be.