Editor’s Note: This story is a part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and success through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

As Keith Langford headed to his hotel room in Miami, he thought: I guess no news is good news.

He and the San Antonio Spurs were playing the Miami Heat in one of their final preseason games in 2007. He knew the final roster needed to be set, but he didn’t know if he would be on it. In the days leading up to that night, he sensed it would come down to him and Darius Washington Jr., another fringe player.

Shortly after he arrived at the hotel, he heard a knock. As Langford nervously opened the door, he was confused to see Gregg Popovich, his head coach.

“Automatically, the butterflies are going,” Langford said.

Typically, when a player was cut, Langford said the team manager or another lower-level employee would show up with the bad news and a plane ticket. Popovich walked in and sat down in a chair.

“Keith,” he said, “I want to talk to you.”

Langford sat on the bed next to him.

“I really think you’re a good player, Keith, and you have a chance to be a high-level player, I see it in you,” Popovich said. “But right now, I couldn’t get you to be aggressive enough. And I think Darius showed a little more aggression than you did.”

He began to choke up.

“I really felt like you took what I was saying to you and really tried to do it, you just aren’t ready,” he said. “But I can tell you are really trying.”

The two got up and hugged. The memory has stuck with Langford for almost 20 years.

“My experience isn’t that extensive,” he said, “but I did have several experiences with several teams. And he was the only one that made me feel like I was a part of something where I was being paid attention to.”

As it turned out, Langford’s experience with Popovich was not unusual.

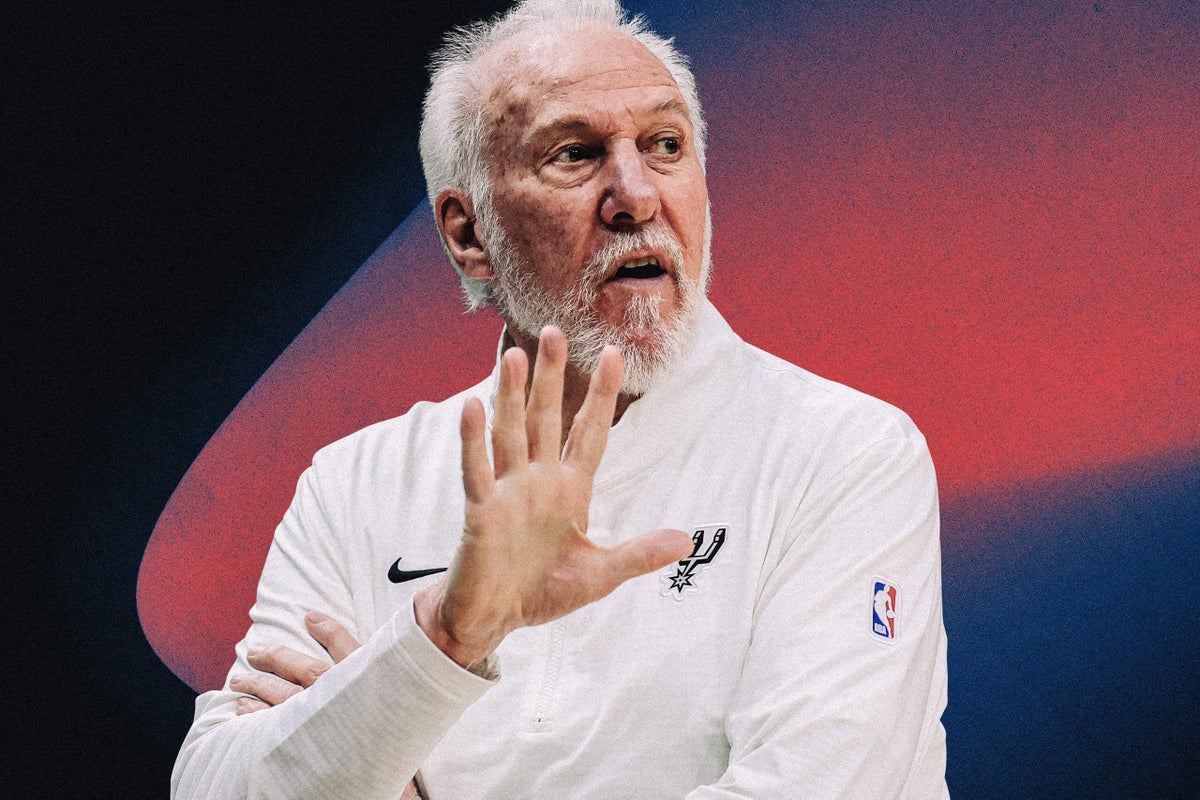

Popovich, who recently retired from coaching at 76, excelled at many aspects of the job during a Hall of Fame career. He built a culture of selflessness, connected with each player and combined discipline with a counter-cultural ethos. He also mastered a crucial skill required by every manager in every company or organization: He understood how to have tough conversations.

In sports, such conversations occur frequently. Players are cut and benched. On a week-to-week or game-to-game basis, their weaknesses are highlighted as liabilities, oftentimes in front of their peers, and drilled down on.

For Popovich, offering blunt feedback in an empathetic way led to stronger relationships and often yielded lasting results.

“I think you have to have accountability,” Popovich once explained. “For us, the thing that works best is total, brutal, between-the-eyes honesty. I never try to trick a player or manipulate them, tell them something that I’m going to have to change next week.”

Why are the most challenging conversations the most impactful? And how can we get more comfortable having them?

Several years ago, researchers Dr. Taya Cohen and Dr. Emma Levine wanted to explore the tension between kindness and honesty. So they conducted a study centered on a simple question: What would happen if people were honest in their daily lives?

Cohen, a professor of organizational behavior and business ethics at Carnegie Mellon, and Levine, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago, assigned participants to one of three groups. One group was told to be kind in all their conversations for three days. Another was told to be mindful of their communication. And the third was told to be honest in every conversation for three days.

Before the study, Cohen and Levine asked participants about their expectations. Not surprisingly, the people in the honesty group thought it would be terrible.

However, when Cohen and Levine checked back in with those same people two weeks later, the main takeaway was clear.

“People expected honesty to be much worse than it was,” Cohen said. “They thought that it wouldn’t be enjoyable, that it would cause all these problems and create conflict. But the reality was it had the opposite effect. Even when it was difficult and they had hard conversations, people said they felt liberated, that it actually strengthened their relationships.”

Cohen said that one of the common reasons people struggle with difficult conversations often boils down to a flawed perception of what kindness entails. By avoiding feedback or criticism, they can feel as if they are protecting someone’s emotions or shielding them from negativity. However, they may be doing the exact opposite.

“We don’t think enough about the long term and how it will be helpful,” Cohen said. “People can handle difficult news often better than we think they can.

So, what is the best way to have these conversations? Cohen believes there are four key components to giving hard feedback.

• Focus on specific behaviors. Cohen said that one mistake people often make is being too vague in their feedback. It’s the difference between “You’re always late” and “At this time for this meeting, you were late.” Keying on concrete behaviors helps people understand clearly what needs to change.

• Explain the impact of that behavior on the rest of the team or group. For example: “The reason we’re having this conversation is we want to address this specific issue because it is affecting our team in this way.”

• Communicate respect for the person in a way that feels authentic. Because these conversations are uncomfortable, Cohen said, people tend to rush through them without taking the time to communicate respect for the person’s work and experience. Even if a tough decision has been made, she said, communicating genuine respect is critical.

• Identify the path forward together. What is a process that will address the problem and lead to change?

During a low moment in K.J. Wright’s career, Seahawks coach Pete Carroll had a difficult conversation with him that Wright has appreciated for years. (Steve Dykes / Getty Images)

K.J. Wright, a former Seattle Seahawks linebacker and now an assistant coach with the San Francisco 49ers, understands both sides of these conversations.

When he was younger, his mom told him, “Son, everybody is not going to like you. You try so hard to be liked by everybody.”

He remembers that conversation vividly, and even as a Pro Bowl-caliber player with the Seahawks, he struggled with not wanting to ruffle feathers.

Just the other day, Wright told Gus Bradley, the 49ers assistant head coach and former head coach of the Jacksonville Jaguars, that he wanted to improve on that.

“I like to sugarcoat a lot,” he told The Athletic. “I like to take people’s feelings into account.”

He also knows how helpful those conversations can be. After 10 seasons with coach Pete Carroll in Seattle, he became a free agent in 2021. As the offseason dragged on, no team reached out to sign him.

“I was going through hell,” Wright said. “Isolated. Confused. Sad.”

Then one day, Carroll called. He asked Wright to talk. They sat down in the team’s weight room, and Carroll laid out the situation.

“It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, you’re coming back. We’re going to make this happen,’ ” Wright said. “It was like: ‘If this opportunity presents itself, this is how it will be if you come back. So many people have to get hurt, you’ll sign for the vet minimum, this is all we can do for you.’ ”

Those words meant the world to Wright.

“It was very honest, very transparent and … very helpful to me,” Wright said. “I’m forever grateful for that moment.”

NFL quarterback Josh Johnson has played for 14 teams, the most in league history, which means he also has had a difficult conversation or two.

“All the times that I got cut,” he said, laughing.

For Johnson, the key wasn’t so much the actual conversation but everything that led up to it. There were times when he joined a team and the coach or front office made it clear from the start that he was a long shot to stick around.

“Which was cool,” he said. “I understood that.”

The ineffective leaders he played for were “wishy-washy,” he said. The effective leaders established the situation clearly and firmly but still worked hard to help him improve each day, even if he was a long shot.

“And then, when that tough conversation comes,” he said, “you’re already prepared for it because you knew beforehand.”

Cohen, the Carnegie Mellon professor, has a saying on this matter.

“Short-term pain, long-term gain,” she said.

What often happens, Cohen said, is people focus so much on the short term: the awkwardness or “emotional harm” caused by the conversation.

“We don’t think enough about the long term,” she said. “That it would be helpful for them to know this information, that people can handle difficult news often better than we think they can. They can learn from it.”

Part of the problem is that people delivering difficult feedback often only see the short-term response. As an example, Cohen pointed to the impact Popovich’s difficult conversations had on players like Langford, something Popovich might never know.

Not long after Popovich and the Spurs cut Langford at the end of the 2007 preseason, he received a call from the team. They wanted him back.

When Langford arrived, Popovich sat him down again, and together they reviewed the areas of improvement that the two had discussed when Langford was cut in Miami.

“He remembered everything,” Langford said.

After that conversation, Langford knew precisely what he needed to work on, what was expected of him and where he stood. And because Popovich was direct, even in pointing out flaws, Langford felt in a better position to succeed.

“He just had a way,” Langford said. “He was in tune, and I had never felt that or had that in my lifetime.”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Megan Briggs / Getty Images)