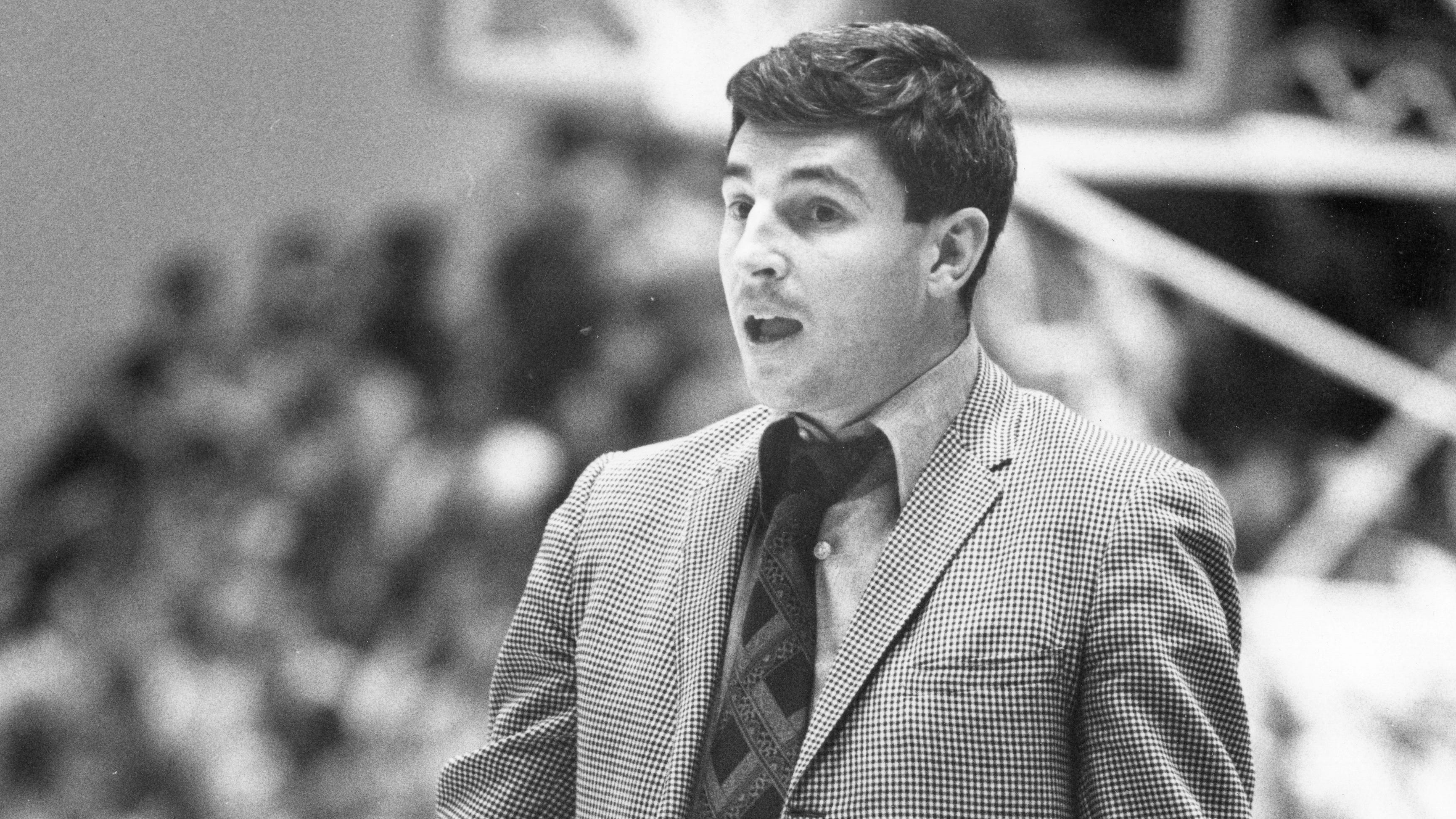

Bob Knight: A retrospective look at the ex Indiana basketball coach

Basketball coach legend Bob Knight passes away at the age of 83.

IndyStar

“His persistent and troubling pattern of behavior has led me to only one conclusion,” Brand said at the press conference announcing Knight’s firing Sept. 10, 2000.When Bob Knight was fired 25 years ago by IU, thousands of students protested.A confrontation with IU freshman Kent Harvey outside of Assembly Hall took place two days before Knight’s firing.

BLOOMINGTON — As a beautiful, autumn Sunday evening fell on the campus of Indiana University, an evening that should have been a sleepy precursor to Monday morning classes, chaos erupted outside the home of IU president Myles Brand.

Thousands of angry students and protesters stampeded toward the stately residence at the center of campus, chanting, pumping their fists into the air and waving their quickly-crafted posters and signs high above their heads.

Don’t trash a legend. Give us back our general. Coach deserved better. Fire Myles Brand.

Those protesters stood for hours outside Brand’s home, as evening turned to darkness, shouting a loud and repeated chorus: “Bobby Knight. Bobby Knight. Bobby Knight.” And “Hey, hey. Ho, ho. Myles Brand has got to go.”

Earlier that day, Brand had fired Bob Knight, the legendary, yet controversial, red sweater-wearing, fiery coach of the men’s basketball team for nearly three decades.

Knight’s dismissal came after a review of his prior incidences of inappropriate behavior led to a zero tolerance policy, which, in a very short time, was repeatedly broken by Knight, Brand said that Sunday 25 years ago.

“His persistent and troubling pattern of behavior has led me to only one conclusion,” Brand said at the press conference announcing Knight’s firing Sept. 10, 2000.

Earlier that morning, Brand had called Knight to let him know IU no longer wanted him as coach. He gave Knight the option to resign. Knight declined.

“And I notified him that he was being removed as basketball coach, effectively immediately,” Brand said. “Unquestionably, this is the most difficult decision I’ve ever had to make.”

The disbelief of Knight’s firing turned to shock, which quickly turned to outrage among the students who scrambled to gather at Assembly Hall within minutes of the announcement. After a 6 p.m. rally that evening, the protesters headed to Brand’s home.

IU police made several arrests that night. An effigy, that looked like Brand, was hung and burned. Fires were set that had to be put out. More than 20 officers in helmets and holding riot shields stood watch.

Some students said officers used pepper spray on the crowd, the Indianapolis Star reported at the time. Others said police dogs nipped at the legs of some protesters.

By the end of the night, the chaos had been quelled with no serious injuries or disturbances. All that remained was a dispersing band of loyal, Knight-loving students who did not want to lose their coach.

‘How fitting that Knight’s final victim was himself’

Not everyone was outraged by the news that IU’s legendary coach was out. Some felt a sense of relief. Plenty of people believed the dismissal of Knight was long overdue.

Bob Kravitz was one of those people. He came to the Indianapolis Star as a sports columnist just months before Knight’s firing, and he was immediately hated by Knight fans. Kravitz was the new guy in town, and he was voicing his very strong opinions against a beloved coach.

“I thought that (Knight had) a reign of terror for quite some time. I thought that he’d lost his edge,” Kravitz told IndyStar last week. “And I just thought that Indiana University did not need to be led around by the nose by a dictator.”

The day Knight was fired, Kravitz was flying to Sydney, Australia, for the Olympics. When he arrived for a 6-hour layover in L.A., Kravitz went to the airport hotel to watch football.

Thirty minutes into the NFL, Kravitz sat shocked as the news scrolled across the ticker at the bottom of the screen. Bob Knight has been dismissed by Indiana University.

“And I’m like, ‘Holy (expletive),'” Kravitz said. “Not that it was unexpected, but you know, it’s a pretty seismic story.”

In the lobby of an L.A. airport hotel, Kravitz wrote his column on Knight’s firing with the headline: “How fitting that Knight’s final victim was himself.”

“So, the sad and desperate fool has done to himself what the university should’ve done so very long ago,” Kravitz wrote. “Even back when Indiana University was winning national titles, but Knight was shaming the school with his embarrassing antics.”

Through the years, Knight had his share of controversy. Chair throwing, technical fouls, verbal attacks on media and, the most talked about, his intense coaching tactics with players.

The same year Knight was fired, former player Neil Reed came forward with a public claim that Knight had choked him during a 1997 practice. Reed’s allegations were supported by a videotape of the incident aired by CNN/Sports Illustrated.

A day after the news broke, Knight denied the allegations, calling them “absurd” and characterizing them as a mixture of exaggerations and outright lies. He told WTHR sports director Don Hein that the journalists responsible for the report should be fired.

“Sometimes, I kind of grab a player,” Knight told Hein in 2000. “Maybe I grab Neil Reed by the shoulder. Maybe I took him by the back of the neck. I don’t know. I don’t remember everything I’ve ever done in practices.”

Knight said any physical contact that occurred was simply an application of the techniques he has used with “100 other players that have been here.”

But Reed’s allegations led to an investigation of Knight’s behavior through his nearly three decades at IU, which led to the university issuing a zero tolerance policy for Knight in May 2000.

That policy read, in part: “Any verifiable, inappropriate, physical contact discovered in the future with players, members of the university community or others in connection with (Knight’s) employment at IU will be cause for immediate termination.”

In the four months that passed after the policy was instated, there were “many instances” where Knight “behaved and acted in a way that is both defiant and hostile,” Brand said at the time.

“These actions illustrate the very troubling pattern of inappropriate behavior that make clear that Coach Knight has no desire, contrary to what he personally promised me, to live within the zero-tolerance guidelines we set.”

The final straw for IU came when Knight had an on-campus confrontation with 19-year-old student Kent Harvey in front of Assembly Hall just before his firing.

“(Knight) reached out and initiated physical contact with the student on his arm, and the two had, according to varied accounts, an uncomfortable exchange,” Brand said. “It is not in dispute that the coach reached out and grabbed the young man’s arm in an unwelcome fashion. The severity of the act is in dispute, however. But the bottom line is that an angry confrontation with a student explicitly violates the spirit and the letter of the guidelines set.”

While some scoffed at the reasons Brand gave for firing Knight, Kravitz, now a columnist and director at Roundtable Media, still believes it was “absolutely warranted and long overdue.”

“But I do think people were shocked. We weren’t sure that Myles Brand had the cojones to do it,” Kravitz said. “And he did, (to his) everlasting credit.

“He had the (guts) to fire The General.”

‘Both sides had some fault’

Twenty-five years after Knight’s firing and less than two years since his death, many of his former players aren’t interested in rehashing or reliving that moment in time.

“Coach Knight means the world to me and has made a profound impact on my life and my career, the type of impact I hope I can have on the players I get the opportunity to coach and mentor,” Michael Lewis, who played for Knight in his final four seasons and now coaches Ball State, wrote in a text to IndyStar. “It has been a long time since his firing and now that he has passed, I prefer to keep my personal feelings as that….personal.”

IndyStar reached out to more than 20 former Knight players. Most either did not respond or declined to comment on this story.

Former player Todd Leary, who hours before had been alerted of what was about to come, watched Knight’s firing play out at a press conference on television. As he watched, Leary said he felt embarrassment for IU.

“I don’t think the school should have handled it the way they did. And I don’t think (Knight) should have handled it the way he did,” said Leary, who played for Knight from 1989 to 1994. “So, both sides had some fault.”

The reasons the university outlined for firing Knight, in Leary’s opinion, did not make sense.

“That same stuff was going on for 30 years prior to that. Why, all of a sudden, at that point?” he said. “It’s like if you have kids, and they do the same thing forever, then all of a sudden you tell them they can’t do that anymore. They’re like, ‘What do you mean?'”

Leary still believes Knight’s firing wasn’t about any zero tolerance policy.

“Myles Brands was not a sports guy. And when you have a non sports person making sports decisions, I’ve never understood how that made any sense,” Leary said. “They definitely had a personality conflict, and that’s just a bad situation, like the whole thing was bad.”

Leary wants to make clear he’s not saying Knight was right and IU was wrong.

“Coach didn’t handle it well, either,” he said. “Anyone who knows Coach Knight well enough will tell you, if you give him an ultimatum or tell him he can’t do something, that’s the first thing he’s going to do.”

Among the things Knight did in those four months under zero tolerance, Brand said, included “uncivil, defiant and unacceptable” behavior.

“There was a continued unwillingness by Coach Knight to work within the normal chain of command in the IU athletic department,” Brand said. “I personally asked Coach Knight, on May 13, to resume the normal chain of command with athletics director Clarence Doninger. He has adamantly refused to do that.”

There were also several attempts by Knight to embarrass the university, Brand said. “In private and in public, Coach Knight has made angry and inflammatory remarks about university officials and the board of trustees.”

Brand pointed to “an instance in the recent past in which Coach Knight verbally abused a high-ranking female university official in the presence of other persons. This angry outburst in his office was completely unnecessary and inappropriate.”

And then, at the end, came Knight’s well-publicized, on-campus interaction with freshman student Kent Harvey. Police talked to nine witnesses who confirmed what happened that September day in 2000.

It started with Harvey offering a “What’s up, Knight?” outside Assembly Hall to the coach as he passed him. Knight, who felt Harvey showed a lack of respect, grabbed his arm and stared him down.

“I looked at him and said, ‘Son, my name isn’t Knight for you,'” Knight said in media reports at the time. “‘It’s Mr. Knight or Coach Knight.'”

And that was enough for Brand and the IU board of trustees. They had given their legendary coach “one last chance” and he had botched it. Two days later, Knight was ousted from the university.

Across campus, Harvey was the villain

The night of the Harvey encounter, Brand called Knight to discuss the allegations. It was 10:30 p.m. Friday, Sept. 8, 2000. As the phone conversation ended, Knight told Brand he was leaving Saturday morning for a fishing trip in Canada.

“Due to the seriousness of the investigation, I requested more than once that he postpone his trip and stay in Bloomington,” Brand said. “He adamantly refused.”

Brand deemed that “gross insubordination.”

The end for Knight came at the detriment of Harvey, who soon was targeted as the guy who had gotten a legendary coach fired. Across campus, students made Harvey the villain.

“Irate Knight fans repeatedly have threatened his well-being by email and telephone,” the IndyStar reported at the time. “Wanted posters bearing his name, telephone number and email address, allegedly, have been distributed across the Bloomington campus.”

The night of the firing, students who weren’t protesting at Brand’s home were protesting Harvey.

“Attn K. Harvey. Directions to new school: 65 N. Exit Lafayette,” one sign read, encouraging Harvey to head to IU’s rival Purdue University.

As Harvey faced the threats, police worked with him to monitor his safety, which included staying off campus and away from classes for the next few days.

IndyStar has reached out to Harvey multiple times for an interview through the years, including on the 20th anniversary of Knight’s firing and upon the coach’s death.

“That event doesn’t define my life, nor does Bob Knight. I don’t think about either anymore,” Harvey wrote to IndyStar in a previous message. “I prefer not to be interviewed about the topic because it was a story that upset a lot of people, and there’s no reason for me to get notoriety on a story that causes people to become upset or angry.”

Knight definitely had his diehard fans, but he also had his diehard critics. And he also had plenty of people who stood by him through it all.

‘Goddammit Alford, you must have left your brain in New Castle’

Steve Alford has never shied away from talking about the positive side of his coach. But, he has also been realistic about what playing for Knight was like.

“Things that coach can and can’t say or do have all changed. And I’m not saying that’s for the better,” Alford, who won a national title with IU in 1987, told IndyStar this month. “He was very, very demanding on me. Very. He put me in my place every day, and that’s what made me better.”

There was shouting, yelling and insults hurled by Knight day after day at practices. One day, Alford tried to make a deal with Knight. When the fury sets in, coach, when a player does something knuckleheaded or idiotic, don’t yell at them.

“Just yell at me. Because when you yell at this guy, he can’t handle it. I’ll handle it,” Alford said he told Knight. “I’ll get it. He can’t get it, but we need him. So just yell at me.”

Knight respected Alford right from the start — so much so that Alford got the Knight treatment right from the start.

Getting thrown out of practices, that usually happened to the seniors, the ones Knight counted on. Alford got thrown out as a freshman. In Alford’s first season on the team, Knight shouted one day in Assembly Hall: “Goddammit Alford, you must have left your brain behind in New Castle.”

“The administration that he worked for when I played there, they were all about excellence, so they understood. Are there going to be some tough things he does? Absolutely,” Alford said. “But if that’s the message that has to be presented to get players and a team to understand what excellence looks like, then we’ve got to follow a leader that understood what excellence looks like.”

Alford, who now coaches at Nevada, said he uses a lot of what he learned from Knight. He has all the notebooks, six of them, from his time at IU when he wrote down what happened in team meetings and on the court.

“And I go back and I look at those things, maybe it’s a discipline thing, maybe it’s a defensive thing or an offensive spacing thing,” Alford said.

Mostly, what he’s taken from those notebooks under Knight into his own coaching career is consistency, toughness and love.

“I knew that as tough as he was on me, he made it very clear how much he cared. And, he loved his players. And, I think in athletics, that is much needed,” Alford said. “You either accept mediocrity and you live in it, or you’ve got to understand ‘no pain, no gain.’

“He could not stand mediocrity.”

‘He was aggressive. He could be a bully.’

To put it simply, Knight was a complicated character, said retired IU psychology professor Dr. Jim Sherman, who struck up a curious, sporadic decades-long friendship with the controversial basketball coach.

After a chance meeting between the two where Knight commiserated with Sherman about his distrust of the media, Sherman got an invitation to sit in on any IU men’s basketball practice any time.

Many days, Sherman took Knight up on that offer. He would walk to the gym and watch from the bleachers while studying Italian. Sometimes, Knight would come over and sit next to him. Sometimes, Knight would give Sherman life advice.

But mostly, at those practices, Sherman liked to be a fly on the wall, watching and analyzing the larger-than-life coach.

“It became clear he did know exactly what he was doing and he really was a great coach,” Sherman said. “He knew exactly what the other team would do, too. What he talked about at practice came true in the game.”

There were outbursts. Plenty of them. “He would get on the kids’ back and he could be pretty brutal,” Sherman said. “He did not mince words.”

Sometimes, though, after Knight berated a player, he would talk psychology with Sherman after practice.

“I can do that with Daryl Thomas and I can do that with Steve Alford,” Sherman recalls Knight telling him. “But I could never do that to Uwe Blab. He would just fall apart.”

There was the softer side of Knight, a man who could be empathetic and kind. and then there was the other side of Knight.

“He was aggressive. He could be a bully. He would not suffer fools at all,” Sherman said. “Often people that aggressive might be people who cut corners or lack ethics. With Knight, you never had to wonder. There is no way he would cut corners when it came to coaching. He was honest, brutally honest.”

Still, Sherman said he saw the antics of Knight that prompted Brand to fire the coach 25 years ago.

“I kind of saw that side of him,” Sherman said. “I never would have treated any of my students or, if I were a coach, any of my athletes the way he did — even if they could take it.”

Leary is certain Knight may have been a basketball genius or, maybe, simply a genius.

“When you talk about basketball, in my opinion, he’s one of the smartest three people? Smartest five people? I don’t know,” Leary said. “But, he’s in that category.”

When Knight called Leary to offer him a scholarship, “I took it. There was no question whatsoever,” said Leary, who had been an IU fan — and a Knight fan — his entire life.

Once at IU, the genius of Knight became clear to Leary, both the good and the bad sides.

“Geniuses are weird or quirky or whatever term you want to use for it,” he said. “They’re all a little nuts in some way. And he was definitely nuts in some ways.”

Knight would go from yelling and screaming at practice to calmly using a history lesson to relate it to basketball. “So I mean, he wasn’t always a complete (expletive),” Leary said.

Then Knight would start screaming again. He liked to throw out jabs and insults to his players, Leary said, but if the tables turned on him, he definitely could not take the joke.

Leary says he is neutral when it comes to Knight. If he’s pushed, he says he leans to the side of disliking his former coach more than he liked him. And Leary, too, is neutral on what happened that fateful September day 25 years ago.

“Who was wrong? Who was right?” Leary says. That doesn’t really matter now. “I will always respect Coach Knight. He was one of the smartest basketball minds that we’ve ever known to this day.”

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on X: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.