April 12, 2013, was just another regular-season night at Staples Center, where the Los Angeles Lakers, backed into a corner by months of struggle and inconsistency, were clawing their way toward a playoff berth.

Their opponent was the Golden State Warriors, a young, fast team still trying to establish themselves. But that night, Kobe Bryant, who was known to play through pain, would meet an unfortunate end to his season.

Bryant’s injury

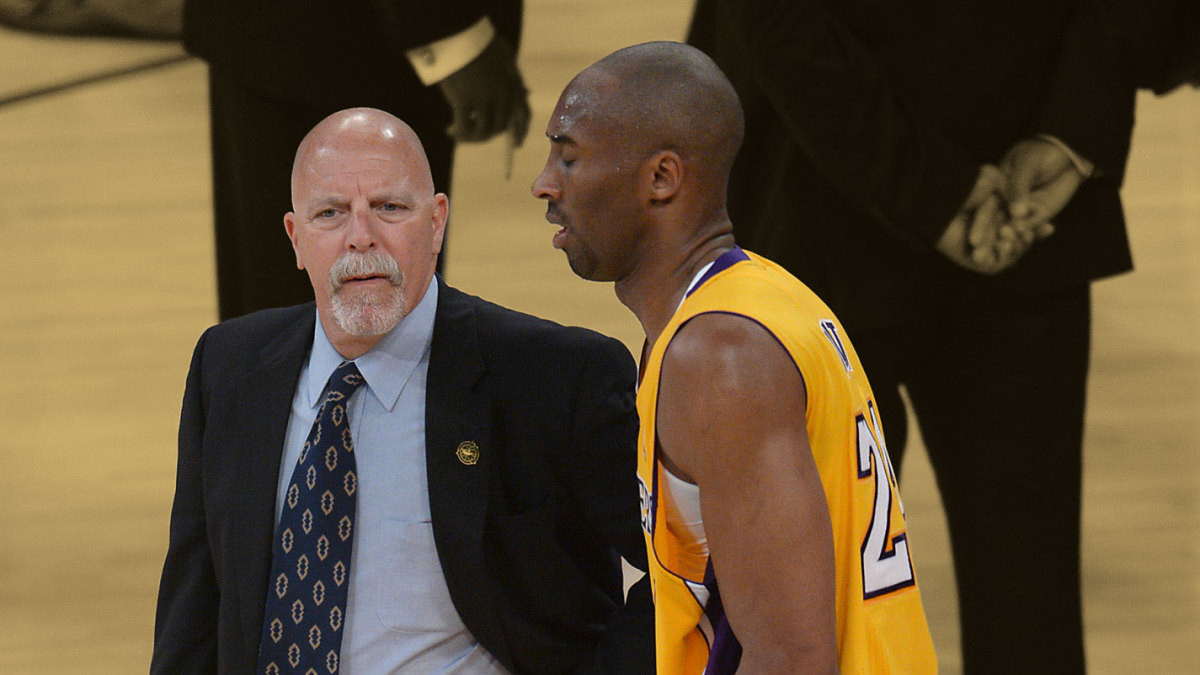

The Lakers guard tore his Achilles as the game wound down. Gary Vitti, the Lakers’ longtime head athletic trainer, rushed to the floor. The two had been through it all — dislocated fingers, broken bones, torn ligaments.

Advertisement

But this was different. “The Black Mamba” still wanted to play.

“He says to me, ‘I reached back there and tried to pull it back down,'” Vitti said. “I know a bunch of athletes since the beginning of my career — rupture Achilles; no one has ever said that to me. And I don’t even know what he was thinking.”

Bryant’s mind at the time was refusing the reality that he had just had a season-ending injury. Reaching for something that wasn’t there anymore, believing maybe he could will it back. At 34 years old, he dragged a battered, aging Lakers team toward the finish line.

Mike D’Antoni, the team’s head coach, had been leaning on him with impossible minutes: 45, 46, 47 — night after night, game after game. In the seven games leading into the Warriors clash Bryant averaged 45.6 minutes per game, playing nearly every second. The burden was visible in the way he moved, slower on cuts, slower rising off screens, favoring his legs even as he carried the franchise’s entire postseason hope.

Advertisement

That night, the five-time champion had already twisted his knee and hyperextended his left leg in earlier sequences. But with three minutes left in the fourth quarter and the Lakers trailing, he planted, pushed off, and collapsed. No contact. Just a sudden, snapping collapse.

He reached down behind his left leg, confused, and felt nothing.

Staying resilient

The Lakers were locked in a playoff race, barely holding on to the eighth seed. A single loss could end everything. Bryant, even on a torn Achilles, wasn’t thinking about surgeries or rehab. He was thinking about the free throws.

Advertisement

He turned to Vitti and asked if he could tape it, run on his heel, or find a way to fix it — just enough for him to finish the game.

“I said, ‘Here’s what I’ll let you do,” Vitti said, recalling his conversation with Bryant. “So you got fouled. There’s two free throws coming. If you don’t shoot them, then Mark Jackson is going to pick somebody on our bench to come out and shoot the free throws.”

“Vino” nodded, dragged himself to the line, and sank both shots. Only then did he walk, on his own, with a torn Achilles, off the court and into the tunnel. The Lakers would go on to win that game 118–116, but the damage was done.

The injury ended the two-time Finals MVP’s season. It would be eight months before he returned to the court. And even then, he was never quite the same. Over the next three seasons, he played in just 107 of 246 possible games, dogged by injuries and setbacks. The Achilles rupture had shattered a version of Bryant that had seemed untouchable.

Advertisement

Vitti, who worked with Bryant for two decades, had never seen anything like it. He’d taped thousands of ankles, iced hundreds of knees. But no one, before or since, had tried to fight through a ruptured Achilles just to keep competing.