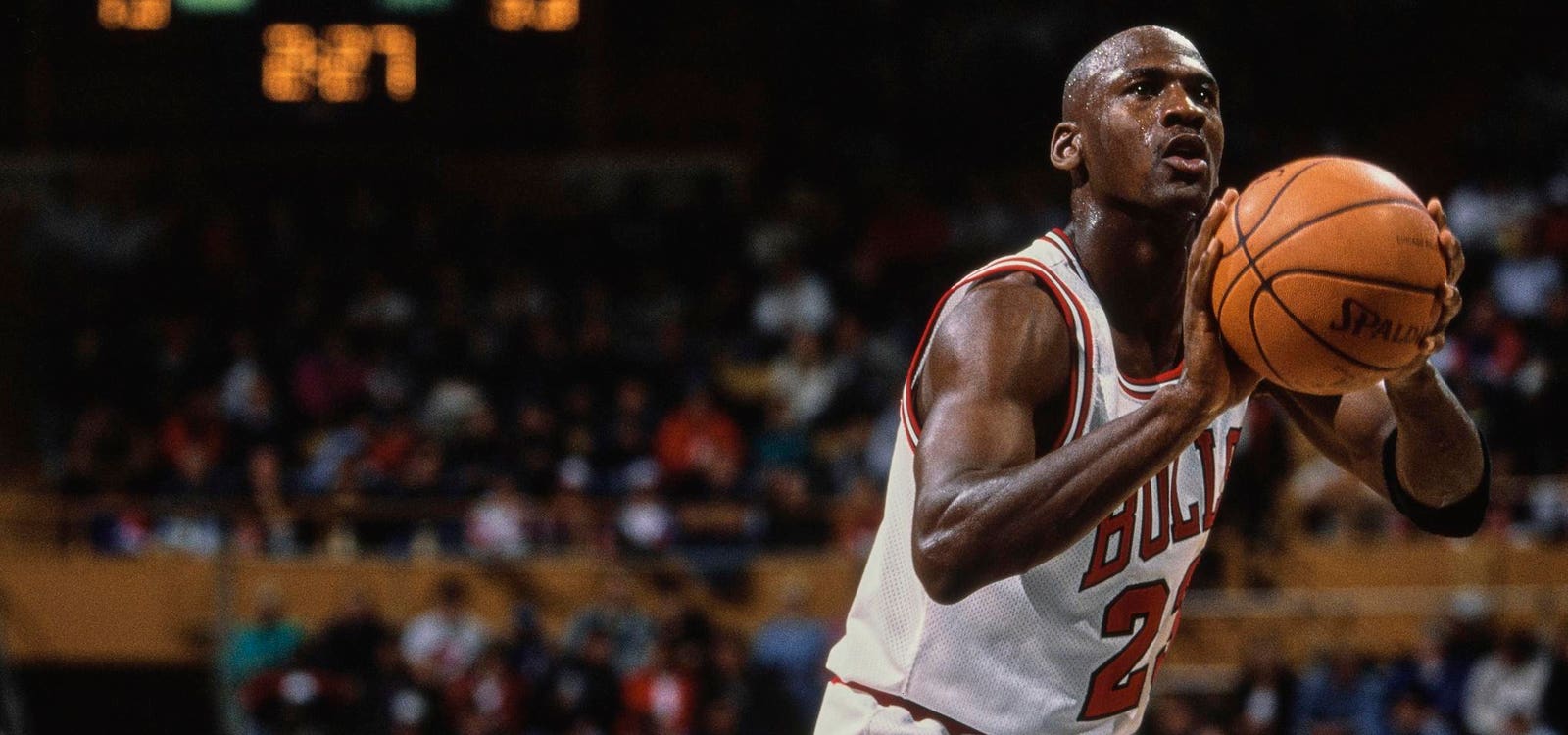

Michael Jordan (Photo by Rick Stewart/Allsport/Getty Images)

Getty ImagesThe Star And The Team Player

Too often, we confuse star performers with ideal leaders. But the real secret to sustained team success may lie not with the high scorers (or the equivalent in the business world), but with the quiet contributors who make everyone around them better. These so-called team players can have a profound impact. Yet, all too often, they remain overlooked.

Take, for example, the story of the Chicago Bulls in the Michael Jordan era. Jordan was a one-man phenomenon. Already in his first year, he scored an average of 28.2 points per game (for comparison, the current top scorer, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, had a rookie season average of 10.8 points per game). By his third year in the NBA, Jordan averaged 37.1 points a game—nearly half his team’s total on most nights. Not surprisingly, he was the team’s captain.

And yet, despite his leadership role and despite his record-breaking output, the Chicago Bulls didn’t win championships. Not yet.

That changed in 1991, when Phil Jackson (who took over as head coach in 1989) made a surprising move: he named Bill Cartwright, a middling center with bad knees and underwhelming stats, as co-captain alongside Jordan.

To understand just how counterintuitive this was, consider how one sportswriter described Cartwright: “He was clumsy and unflashy, had terrible knee problems, didn’t block many shots, and couldn’t catch passes unless they were thrown directly at his nose.” At one point, Jordan reportedly told teammates, “If you ever pass it to Bill, I will never pass it to you again.”

But, to everyone’s surprise (except presumably Coach Jackson’s), the move worked. The Bulls started consistently winning, including the NBA championship that year, their first of six that decade.

Why did the appointment of a mediocre player as co-captain have such a profound effect on the team’s performance?

The Science Behind Team Players

In the decades since Jackson’s unconventional move, science has come a long way to explaining what the Bulls coach seems to have known intuitively: that certainly individuals, who might not be outstanding performers in their own right, can have a profound impact on the collective performance.

For example, Harvard University researchers Ben Weidmann and David Deming have found that some individuals are able to, “consistently cause their team to exceed its predicted performance.” These individuals, whom they call “team players,” are not necessarily smarter or more productive than others. But they stand out for their exceptionally high social skills.

In the Bull’s case, this was Bill Cartwright. He was a terrible performer. And yet Jackson saw something else. Cartwright was the emotional glue. He supported younger players, brought calm to the locker room, and created trust on and off the court. As Jordan later admitted, “Bill made all the difference.”

That’s the hidden effect of true team players, those who who don’t dominate the scoreboard but who elevate everyone else. And it’s not unique to basketball. If you look carefully enough behind many a blustery, performance-obsessed leader in history, we find a co-leader whose steady and calming influence ensured that group cohesion.

Tim Cook and Sheryl Sandberg, for example, played critical roles in stabilizing growing companies under obsessive and performance-focused CEOs (Apple under Steve Jobs and Facebook under Mark Zuckerberg). George C. Marshall, US Army Chief of Staff during World War II, held the war effort together through his exceptional organizational and interpersonal intelligence (not to mention logistical genius). Of course, his behind-the-scenes work garnered far less attention than the front line heroics of the likes of George Patton and Douglas MacArthur.

Balancing A Focus On Performance With A Focus On People

Of course a Cook or a Cartwright alone can’t get you a championship team or organization. In the Bull’s case, Jordan was fundamental too. But not just because of his high scoring average.

A recent study in Applied Psychology by Laura Parks-Leduc, Susan L. Dustin, Gang Wang, and Taylor W. Parks found that teams in which some individual members prioritized collective values (what they called “benevolence values”)—things like cooperation, dependability, and support—outperformed others. These values didn’t always align with top individual performance. But they had a significant effect on team performance as a whole. In the case of the Bulls, this is what Cartwright brought to the table.

But, in addition to these benevolence values, they found that another necessary ingredient for top performing teams: having an individual who prioritized “achievement values”—hustle, grit, and a relentless drive to perform. These were values Jordan fully embodied.

Teams that have individuals foregrounding both sets of values are able to rise above the rest. This was one of the secrets behind the Bulls: while Jordan pushed the team with relentless intensity, Cartwright created the environment in which that pressure could lead to progress—not burnout.

Why We Overlook Team Players

If team players like Bill Cartwright are so essential, why are they so often overlooked—or worse, dismissed as under-performers? The answer lies in a bias that still dominates how most organizations identify leadership potential: we assume that the best performers will also make the best leaders.

That’s understandable. High performers are easy to spot. Their numbers dazzle. They take up space. They “look” like leaders—confident, competitive, commanding. But performance, as decades of research now shows, is not the same as impact. A truly great team needs more than visible stars. It needs glue players—the ones who build trust, model reliability, and make their teammates better, even if they’re not topping the leaderboard themselves.

The problem is, these Cartwright-types don’t always shine in traditional evaluations. They may be awkward. They may underwhelm in presentations. They might even, like Cartwright, drop the occasional pass. Shane Battier, who was the “Cartwright” for the championship Miami Heat in the 2010s, has pointed out that he touched the ball only around 2% of the time. He, too, is someone who is easy to overlook. But dismissing them means missing a crucial opportunity. As I’ve argued in my book The Unseen Leader, the individuals who quietly elevate those around them, like Cartwright and Battier, are often the key to sustained excellence.

The challenge for business leaders is to get better at recognizing these unsung contributors—and more courageous in promoting them. That requires rethinking how we define leadership potential. It means looking beyond charisma and confidence, and starting to value those who build climate, not just those who chase metrics. Phil Jackson saw that.

To be fair, promoting Cartwright was not the only secret to his team’s success. Yet it may stand out as his boldest decision: he gave the co-captaincy not to another superstar, but to someone who helped the superstars succeed. He understood the potential effect of elevating a team player to a position of responsibility. This decision helped create one of the most dominant teams of a generation. The business world could learn a lot from that kind of play.