At the 3:56 mark of the second quarter of the Golden State Warriors’ bout against the Cleveland Cavaliers — with the Cavs taking free throws at the charity stripe — Brandin Podziemski, often the designated play caller on the floor that makes him an extension of Steve Kerr and the coaching staff, communicated to his teammates which play they were going to execute after the Cavs’ free throws. Podziemski promptly makes a motion with his thumb sticking out, while also seemingly mouthing the words, “thumb out.”

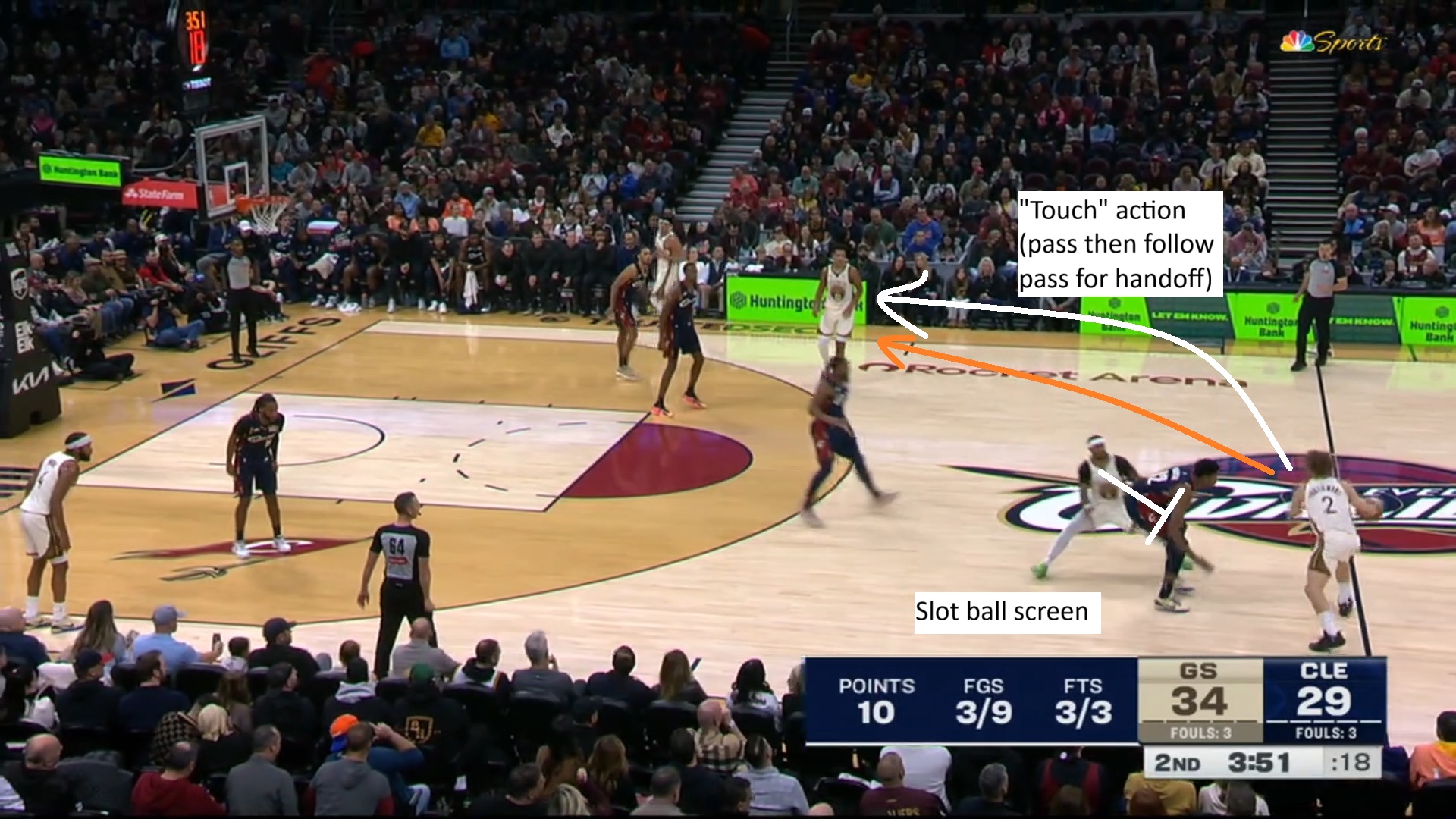

The “Thumb Out” play has been a staple of Kerr’s offense for several years. In its simplest form, it is a side/slot-area ball screen, followed by “Get” or “Touch” action, which is a pass to a big on the opposite side, followed by the initial ball handler following his pass to get the ball back on a handoff:

The initial ball screen, followed by “Touch” action, makes this set a virtual double ball screen action. After Podziemski comes off of Trayce Jackson-Davis’ handoff, Jackson-Davis re-screens by flipping the direction of his pick — which finally forces the Cavs’ defense into rotation, with Gui Santos “shaking” or lifting from the corner to the wing. When Podziemski sprays the ball to Santos in the middle of his lift, Santos immediately attacks off the catch, which puts the already-spinning Cavs defense deeper into the proverbial blender.

Amid the chaos, Gary Payton II takes advantage of virtually zero eyes being dedicated to him, courtesy of a “blade” cut from the weak side:

While the possession above was indicative of good offense at that very moment, the bigger picture told a very different story. The Warriors only managed to score 104.2 points per 100 possessions in the game — offset by the Cavs’ even more meager 97.9 points per 100 possessions. Coupled with a defense that was up to the task, the Warriors managed to squeeze just enough juice from the proverbial offensive orange. Even so, it was symbolic of an offense that has largely struggled, even with Steph Curry and Jimmy Butler healthy and especially pronounced with the both of them sidelined.

As a result, Kerr had to assemble a ragtag bunch of youth, two-way contracts, and role-player veterans, all just to attempt to put out a squad that, at the very least, resembled a baseline NBA team. What Kerr got from the rest of the healthy, available roster against the Cavs — all 10 of them — was just enough NBA quality to overcome a more talented Cavs roster.

In an effort that could be described best as a win by committee, the head of the offensive department of that committee was Pat Spencer, who notched his career high in points (19) while also tallying seven assists and four boards. Spencer showed adept skill that belied his status as a player on the margins of the league, with ball-handling and pick-and-roll chops that were supplemented with steadiness and calm decision making.

Off the ball, his refusal to remain a stationary target placed an emphasized the concept of “motion” in what has been known as a motion offense — a concept that even some on the team have yet to completely internalize. Spencer understands that, like Curry does on a consistent basis, staying in motion is to keep the defense constantly guessing. A defense that constantly has to operate on the back foot will find it difficult to cover every base; eventually, a gap opens for an offense that is primed and ready to capitalize:

A huge reason for Spencer’s uptick in minutes — and earning a starting spot over Podziemski — was an inherent internalization of how to be a cog in the larger machinery. By accepting his role, he momentarily became larger than life. By slipping through the small cracks (figuratively and literally, exemplified by the backdoor cut below as a response to an ill-advised overplay) he created a chasm through which the Cavs precipitously fell. It was a hole the Cavs ultimately could not climb out of:

Spencer’s mantra of moving both himself and ball was infectious. The belief that the ball has energy and that it spreads throughout the team was perhaps best exemplified tonight, with him as the beacon of that philosophy. If Spencer placed faith in the notion that by moving the ball and spreading the touches around, he would soon find himself with the ball in his hands with a good shot created for him, that faith was repaid:

Again, the attempt to move the ball (and personnel) in order to create good offense was infectious. On this side ball screen for Moses Moody, peep at how everyone else shifts slightly to their right — the same direction as Moody’s drive. With a defense already preoccupied with collapsing toward Moody, Gui Santos immediately pounces by drifting backward from the dunker spot to the left corner. Moody promptly sprays to Santos in the corner:

This offense-by-committee approach served as a sufficient stopgap measure, one that was much needed without any bona-fide advantage creation. Per Databallr, the Warriors’ offense can only manage a paltry 99.8 points per 100 possessions in 261 minutes without Curry and Butler on the floor this season. They managed to better that figure against the Cavs by a slight amount, even if on most nights such a points-per-100-possessions figure wouldn’t suffice. But on this specific night, with the complementary defensive effort to halt just enough of the Cavs’ offense outside of their main trio, the collective effort was just enough to notch a win.