As local officials rally for a new downtown arena for the San Antonio Spurs and a revamped entertainment district they say will boost the local economy, a long-forgotten plan that made the same promises on the city’s East Side more than two decades ago gathers dust.

A finalized 2003 community plan surrounding the brand-new, 18,418-seat SBC Center, later the AT&T Center and now the Frost Bank Center, drew up a vision for $250 million in projects across 7.9 square miles of the city’s East Side. The plan would relocate the Spurs from downtown to East Houston Street, build out an arena district, complete with connected parks and a new town center that would have included mixed-use development.

Despite being dreamed up by the City of San Antonio, Bexar County, the Spurs and a group of community partners, it never came to fruition.

In recent months, more details have emerged about “Project Marvel,” an ambitious vision for a sports and entertainment district in downtown San Antonio. The city-shaping project has become a key issue in the 2025 San Antonio mayor’s race, and community reaction so far has been mixed.

Earlier this month, the city, county and NBA team signed an initial agreement to work together to make a new sports and entertainment district happen, and they plan to hire an executive program manager to oversee its coordination.

Commissioners Court breaks during a public meeting in January at the Bexar County Courthouse. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Commissioners Court breaks during a public meeting in January at the Bexar County Courthouse. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

However, Eastside residents who remember promises made during the 1999 campaign for a new tax to fund the construction of the now-called Frost Bank Center see their window of opportunity for an economic renaissance closing.

“We were told there will be jobs for the communities, hotels, restaurants, stores — empty promises,” said Darīus Lemelle, a leader with St. Paul United Methodist Church-COPS/Metro during a community stakeholders meeting in January. “That we see leaders continue to allow these developers to take our tax dollars for private investment, I say: ‘No more.’”

That meeting drew 200 attendees, who spent three hours discussing what would happen to the Frost Bank Center and Freeman Coliseum — not to mention the neighborhoods around them — if the Spurs leave.

But most of the conversation looked back, not forward.

Willie Mae Clay, a community member, voices concerns about accessibility on future projects at the Frost Bank Center during a town hall meeting in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Willie Mae Clay, a community member, voices concerns about accessibility on future projects at the Frost Bank Center during a town hall meeting in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

“[At the time], we were excited to know that here comes a new opportunity for development and the Spurs finding a new home,” said Rev. James Amerson, a pastor at the St. Paul UMC church that was founded in 1866, seeing the city through years of racially biased housing practices called redlining and the growth of a Black community on the East Side.

“So there were lots of conversations about, ‘Wow, this is going to be great for the East Side,’” Amerson said, adding that the relocation brought hope to the historically underserved community.

When asked to reflect on the Spurs’ departure from the Alamodome, about a half-dozen city and county leaders couldn’t recall specific promises that were made, but all agreed it was broadly believed that significant development would follow the arena’s move east.

No contractual promises of East Side investment are clear in the original documents signed by the county, Spurs and San Antonio Rodeo surrounding the move.

However, the city, county and Spurs worked with a nonprofit economic development group called the Community Economic Revitalization Agency (CERA) to fund and create the 156-page Arena District Community Development Plan — which later became known as the Arena District/Eastside Community Plan.

Few of its recommendations ever became a reality, and it appears it has gradually been forgotten over time.

A heated history

When discussions started in 1999 about where to build a new arena, a hot contest broke out between the city and county to see who could woo the Spurs into supporting their preferred location and ways of paying for it.

While the city, under the late Mayor Howard Peak, wanted to build the new arena downtown next to the Alamodome utilizing a sales tax initiative, then-Bexar County Judge Cyndi Krier wanted to place the arena next to the Freeman Coliseum on the East Side using funds from visitor taxes, increasing the county’s hotel occupancy tax and motor vehicle tax, which applies to rental cars.

Krier did not respond to multiple requests for an interview for this story.

Her successor, Judge Nelson Wolff, wrote in a memoir titled “Transforming San Antonio” that Krier recalled one of the commitments she made when she first ran for county judge in 1992 was to improve the facilities for the rodeo, and she saw the new arena as an opportunity to make good on that promise.

Peak, on the other hand, told Wolff he was pulling for a location next to the Alamodome to help ensure the then-still-new stadium didn’t go to waste. Peak repeatedly turned down offers for the city and county to work together with the Spurs, Wolff wrote.

“Peak was not in the mood for compromise,” Wolff wrote. “[He felt] the city and county should continue to work on their own plans … and once the Spurs decided which plan to accept, the city and county should work together in unison to see how each one can help the other.”

Eventually, the county beat out the city by promising the Spurs operational control of the new arena, Wolff said in the memoir.

With the support of the Spurs and the San Antonio Rodeo, Bexar County was able to convince voters to approve the visitor tax increases. The new arena was built under a public-private partnership, utilizing $175 million raised by the county through those taxes.

They did the convincing with an election-year campaign in 1999 — in the months after the team was riding high from its first NBA championship — dubbed “the Saddle and Spurs campaign.”

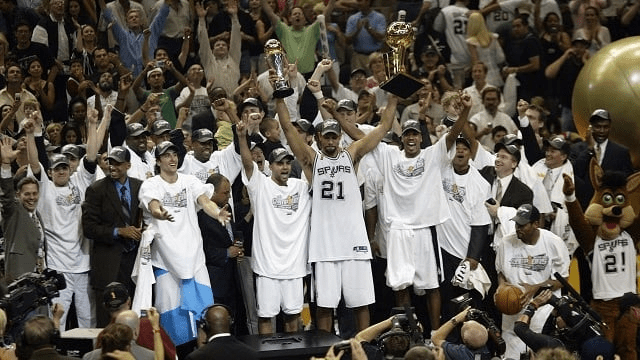

David Robinson and Tim Duncan led the Spurs to victory in June, and voters gave their approval to the arena funding in November.

“Of 599 voting precincts, only 45 went against the arena,” Wolff wrote in his memoir.

Following their move to the East Side, the team saw incredible success under Coach Gregg Popovich and the team’s “Big Three,” Duncan, Manu Ginobili and Tony Parker, who helped the franchise wrangle an additional four championships in 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2014.

The San Antonio Spurs win a championship in 2005. Credit: Courtesy / Texas State Historical Association

The San Antonio Spurs win a championship in 2005. Credit: Courtesy / Texas State Historical Association

But while the team drew thousands of fans to the East Side — averaging about 18,000 in home game attendance in good years — the majority got right back on the highway after the final buzzer.

“What we see today is, traffic comes into the Frost Bank Center with tons of people getting off of I-35 or I-10, and then they’re funneled right back out,” Amerson said. “So there’s been no economic development, and certainly between downtown and the center there hasn’t been any improvement in residential infrastructure.”

The forgotten plan

The San Antonio Report reviewed copies of the contracts written up between the county, Spurs, Rodeo and the Coliseum Advisory Board for the construction and operation of a new arena.

No mention of dollars specifically going into the East Side is made in the legal documents, though the documents do contractually hold the Spurs to paying the county back over 25 years, and to also giving the county 20% of its profits per fiscal year over 20 years.

Some residents say they believe those dollars were meant to be reinvested into the East Side, though the documents do not specify how the county would use them.

In a phone interview earlier this month, Wolff said the Spurs have never given Bexar County any of their profits since the contract was drawn up and signed. Spurs Sports and Entertainment did not respond to a request for comment.

“You know how much the county has got? Zero,” he said. “So either it (the Frost Bank Center) doesn’t make money, or something’s wrong.”

During negotiations to finalize the contracts in 2000, then-County Commissioner Tommy Adkisson (Pct. 4) proposed that the Commissioners Court collaborate with the city and other entities to secure funding for an Eastside neighborhood plan, which would include the redevelopment of the Freeman Coliseum.

Two years later, county commissioners authorized spending $50,000, with the same amount contributed by the City of San Antonio, the San Antonio Spurs and CERA to create the plan by “seeking professional guidance and ideas to further promote the positive development of the Freeman Coliseum, coliseum grounds and the Eastside communities.”

In total, $200,000 was spent to create the Arena District Community Development Plan.

It took about a year to develop and finalize, and included input from 15 Eastside neighborhoods and community groups, 16 “community stakeholders,” and an 18-member steering committee that included representatives from the county, city, Spurs, and local neighborhood associations.

Representatives on the plan’s steering committee included Adkisson; former Councilman John H. Sanders (D2); Raul Ramos of the Coliseum Advisory Board; Leo Gomez, who worked for the Spurs at the time, and six neighborhood association leaders.

From there, the entities subcontracted with the Economics Research Associates, SWA Group and Laura Thompson Associates to author the report.

They held three community meetings on the East Side with 218 total attendees, representing 654 hours of citizen participation, according to the finalized plan. It was published for the public in December 2003 and was adopted as a component of the City’s Comprehensive Master Plan.

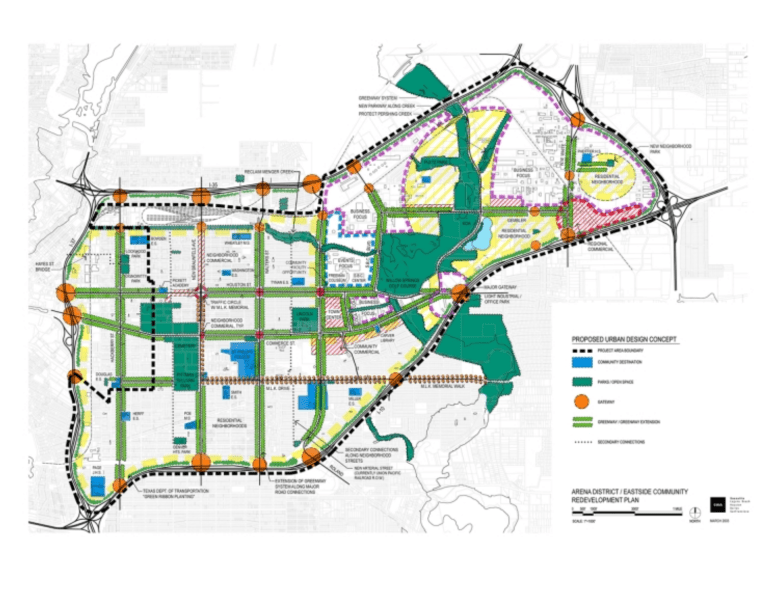

The plan included four parts: a real estate market evaluation; suggestions for land use and community facilities; transportation and infrastructure; and recommendations for plan implementation.

Under real estate, the plan set goals for construction of between 25 and 50 new homes each year for 10 to 15 years, 600,000 square feet of new industrial space by 2018, and 200,000 square feet of new retail space by 2018.

It also called for additional green space, more sidewalks, more shaded bus stops and resurfaced streets.

Most notably, the plan called for the creation of a new town center — a central, commercial area of a town, serving as a hub for the community. This town center was supposed to create a new mixed-use space that included retail uses such as a grocery store and shops, but also more community-oriented facilities such as a bank, medical facility, and/or library.

A rendering of the new Eastside town center shows it was meant to be a mixed-use development zone that would include new retail and office space, as well as access to green space and residential developments. Courtesy/The Arena District Community Development Plan, 2003.

A rendering of the new Eastside town center shows it was meant to be a mixed-use development zone that would include new retail and office space, as well as access to green space and residential developments. Courtesy/The Arena District Community Development Plan, 2003.

“All these uses can co-exist in a well-planned development that is a combination of two to three-story buildings interspersed with open spaces and plazas and accessed by pedestrian-friendly streets,” the finalized plan reads.

It compares town centers such as Southlake Town Square and Highland Park Village in the Dallas-Fort Worth area for inspiration.

However, its implementation stalled.

The plan called for the creation of a centralized development “authority” to “pull together the financial resources to rapidly generate the level of investment that will be required to move the program forward.”

While CERA had largely taken the lead in pursuing Eastside revitalization efforts up to that point, the organization’s nonprofit status placed a “clear constraint on its financial capacities,” the report said.

Even the report’s authors acknowledged that prioritizing these recommendations would be a challenge.

“The City of San Antonio and Bexar County have numerous economic development initiatives that are ongoing, and may have difficulty (in and of themselves) in prioritizing the Eastside in comparison with other projects, such as the new Toyota plant now planned for the south side of Bexar County,” the plan states.

Fans watch and cheer as Rookie Victor Wembanyama, the San Antonio Spur’s first overall draft selection from France plays in his first regular season NBA game against the Dallas Mavericks at the Frost Bank Center. Credit: Scott Ball / San Antonio Report

Fans watch and cheer as Rookie Victor Wembanyama, the San Antonio Spur’s first overall draft selection from France plays in his first regular season NBA game against the Dallas Mavericks at the Frost Bank Center. Credit: Scott Ball / San Antonio Report

Still, its authors argued that the Spurs’ move east gave the plan a rare chance to succeed.

“Given the extent of reinvestment that the Eastside requires … revenue opportunities created by an Arena District authority need to be seriously evaluated,” it states. “This is an immediate priority; [Economics Research Associates] expects Bexar County officials and the Spurs to take the lead in pursuing this element. ERA understands that all of the above ‘entity’ options have challenges.

“At minimum, the county and Spurs should seriously consider pursuit of additional taxes on arena / coliseum parking and / or event attendees, and target this income entirely to Eastside revitalization,” the report said.

It’s unclear if a central Arena District authority was ever officially formed. In 2008, CERA was renamed and re-aligned to become the San Antonio for Growth on the Eastside (SAGE), which still works to promote economic development in underserved areas.

Even with the creation of a federal “Promise Zone” in 2014 that came with $366 million in federal grants and other investments, according to SAGE, many of the goals in the Arena District/Eastside Community Plan remain unfulfilled today.

The Promise Zone designation expired in 2024.

How to win over voters

Of the former city and county officials the San Antonio Report spoke to for this article, none of them recalled any sort of specific promises made to the East Side or its residents.

Wolff said it’s likely that there were promises made to the residents to gain support behind the tax campaign, although he added he was on the periphery of the initial push because he was not yet county judge at the time.

Another such campaign will likely have to be run to gain voter support for Project Marvel.

Ed Garza, who became mayor after Peak, said he couldn’t think of anything specifically promised to the residents.

“I don’t think there was anything specific in terms of — I can’t recall the county promising anything at any public meetings … other than just the indirect benefit of having a stadium in the area,” Garza said.

Garza added that those lingering feelings of the East Side being ignored in arena plans likely go back to the Alamodome days in the early-1990s. Some Eastside community members have outright fought against development there, he noted, due to worries it would price longtime residents out of their homes.

“You could argue over time there has been some development, and it has spilled into the East Side — but then again, some would say, ‘Well, that’s gentrification,’ and then you have that whole argument of if these projects bring gentrification,” Garza said.

New uses proposed in recent weeks by County Commissioner Tommy Calvert (Pct. 4), who was originally shut out of Project Marvel discussions, include a new golf course, a year-round rodeo or a multi-use development that includes a new hotel, restaurants and offices.

Bexar County Pct. 4 Commissioner Tommy Calvert listens to public commentary at a town hall meeting in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Bexar County Pct. 4 Commissioner Tommy Calvert listens to public commentary at a town hall meeting in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary and longtime San Antonio politician Henry Cisneros, who championed the construction of the Alamodome, said he also doesn’t recall any specific promises, but added that looking forward, the Frost Bank Center could still potentially contribute to the East Side.

“I think it’s still possible to do something substantial for the East Side. Even if the Spurs are not in the Frost Bank Center, other uses for the arena could still prove prosperous,” he said this month.

“If I were an Eastside activist, I wouldn’t give up,” he said. “I’d keep fighting for a mix of uses.”

Reporter Shari Biediger contributed to this report.