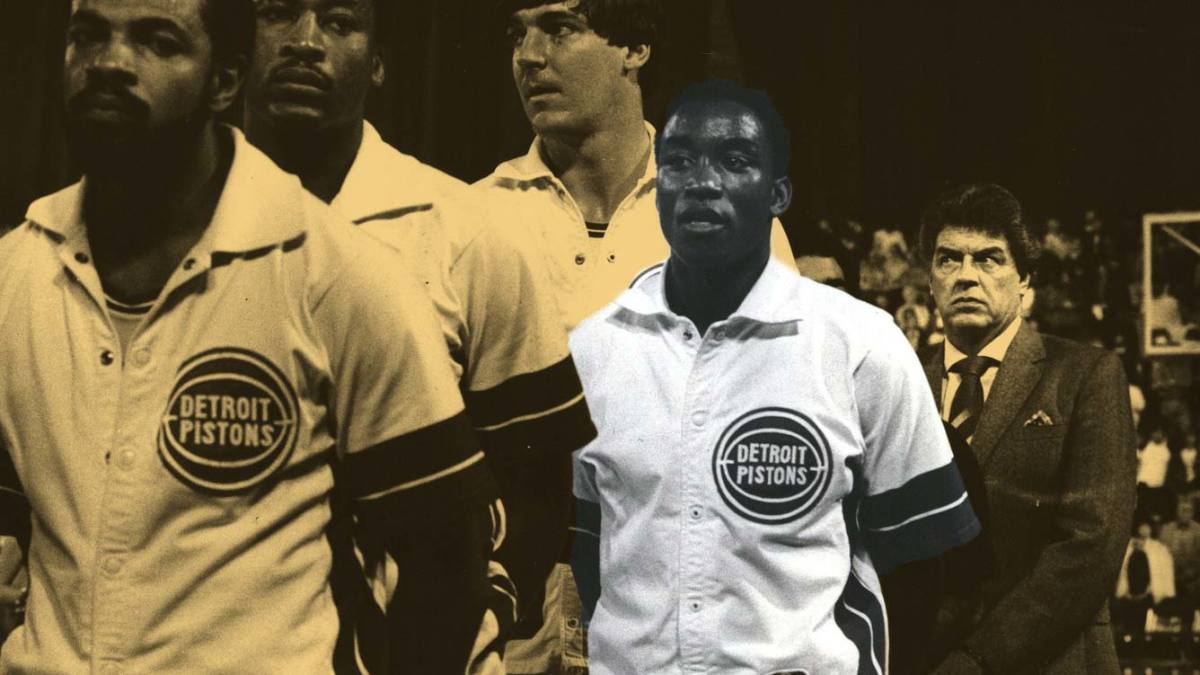

For much of the late 1980s, no NBA team wore the villain’s cape quite like the Detroit Pistons. They were the bruisers of the league — defined by sharp elbows, body checks in the paint and scowls that lingered longer than postgame handshakes.

Dubbed the “Bad Boys,” their basketball was synonymous with street fights in shorts and the reputation stuck hard. But according to former team captain Isiah Thomas, much of what fans saw — and believed wasn’t the full story. The narrative, he insists, was just simplified in one negative direction.

The narrative that stuck

The Bad Boys embraced physicality, no doubt about it. They thrived in games where finesse got left in the locker room. But “Zeke” believes their portrayal as instigators, as the NBA’s only enforcers of chaos, was grossly exaggerated. Especially when they were often just returning fire.

Advertisement

“We had the reputation of fighting and throwing, but we was hitting back,” the Hall of Famer said. “Like Laimbeer finally stood up and hooked hit Robert Parish back. Parish beat Laimbeer down and it’s on film. But the narrative and the way they described our fights is — what you seeing is not what they are telling you.”

The Pistons didn’t tiptoe around their style. They were aggressive, confrontational and unapologetic about it. But to Thomas, that label of being the ones who “always started it” became a convenient truth for the rest of the league.

One of the most striking examples the point guard points to happened in the 1987 Eastern Conference finals. Game 5 between Detroit and Boston turned into a cold war on hardwood. In a moment still frozen in infamy, Celtics big man Robert Parish landed two hard punches to Bill Laimbeer’s face, sending him crashing to the floor.

Bloodied and stunned, “Lambs” never retaliated — and more shockingly, neither a foul nor an ejection was called on Robert. It was just a case of rough play and a brutal moment in a high-stakes game. And yet, it flew under the radar.

Advertisement

No media frenzy, no league crackdown. For Isiah, that moment represented something larger: the double standard that dogged Detroit throughout its championship pursuits. The ones that are often talked about are the brawls that Bill retaliated against.

While Laimbeer became a household name for his scrappy, confrontational approach, Parish rarely got labeled with the same fury, even though his altercations, like that one, were anything but passive. The Pistons center, however, was vilified.

Being the villains

As Thomas sees it, the league and the media needed a scapegoat for the shift from Showtime flash and Celtics precision to bruising Midwest defense. The Bad Boys became an easy target.

Advertisement

The Pistons’ hard-fought style came with a cost, an image that overshadowed their basketball. That perception often overwhelms reality. That team played hard-nosed basketball and was framed as disruptors of the game itself.

“They’re telling you, ‘Oh, look at the Pistons fighting.’ They not telling you, ‘That dude hit him and he’s hitting him back,” the legendary point guard added. “We got them thinking about fighting, not we playing basketball.”

That framing came to a head in the 1988 NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. Game 6 remains one of the most controversial in Finals history. With Detroit just minutes away from clinching their first NBA championship, Laimbeer was whistled for a foul on Kareem Abdul-Jabbar after he put his arms up to block a shot — a call that remains hotly debated decades later.

Replays showed minimal contact. The call sent Abdul-Jabbar to the line, where he calmly drained two free throws. The Lakers escaped with a one-point win, 103–102 and then took Game 7 for the title.

Advertisement

It wasn’t just a game-losing call. For the Pistons, it felt like their bruiser image was working against them, influencing how the referees called pivotal moments. Detroit would go on to win back-to-back titles in 1989 and 1990, finally shaking off the stigma with rings. But the notion that they were villains and antiheroes in an era of elegance still persists.

Over time, the league adopted a more physical tone, particularly in the ’90s, when the New York Knicks and Miami Heat embraced defensive brawls. But the Bad Boys were the blueprint — and the ones who paid the social cost for it.