While serving his country during the Korean War, Earl Lloyd paused his NBA league shortly after he had become one of three players to integrate the league. But he later made more history in Detroit.

The date was October 31, 1950. Instead of a Halloween costume, Earl Francis Lloyd wore a Washington Capitols basketball uniform as he took his well-earned place on a court at Edgerton Park Sports Arena to become the first Black player to appear in a National Basketball Association game.

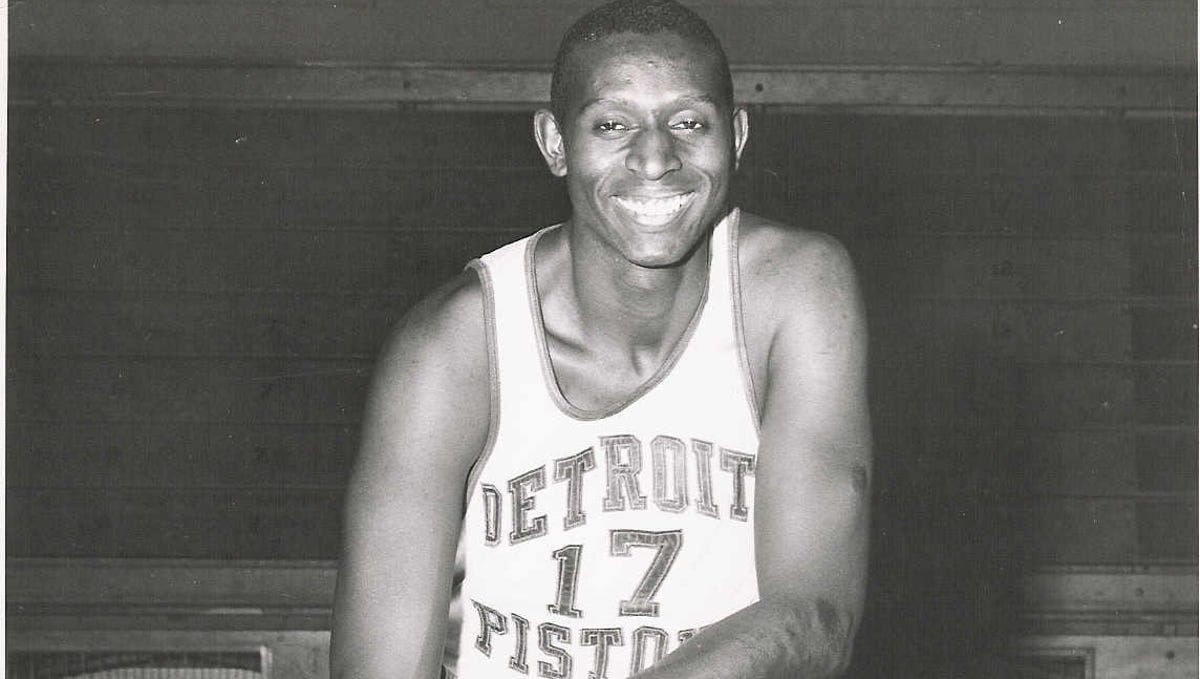

In a game won by the Rochester Royals, 78-70, in front of 2,184 paying fans, Lloyd — a 6-foot-6-inch forward known for his tenacious defense — proved he belonged on the court by collecting 10 rebounds to go along with six points and five assists. Lloyd’s performance contributed to a groundbreaking moment in the NBA’s history that can still be felt as Lloyd, along with Chuck Cooper and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, integrated the league that season.

On Oct. 2, the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association announced that the 75th anniversary of the three “NBA Pioneers” will be celebrated by the NBA throughout the 2025-26 season.

However, an examination of Lloyd’s historic rookie season with the Capitols reveals that he only played seven games because, as the Associated Press reported on Nov. 7, 1950, Lloyd, a Virginia native and former standout at West Virginia State University, was “ordered to report to his Alexandria, Va. draft board for Army induction on Nov. 16” of that year.

Lloyd would proudly serve his country for two years in the United States Army during the Korean War, but he was far from done when it came to making history in the NBA. And much of that continued history would be made with the Detroit Pistons, an organization where Lloyd provided veteran leadership as a player before becoming a trailblazer as a scout, assistant coach and head coach during a period spanning from the late 1950s into the early 1970s.

“From the time Earl Lloyd arrived in Detroit, the Pistons and the city received a refined, dignified and intelligent man, who pushed himself and maintained the highest standard in every position he ever held,” said Ray Scott, who received a home visit from Lloyd before the Pistons drafted Scott fourth overall in the 1961 NBA Draft as a forward/center. “When I played for the Pistons, Earl Lloyd was the guy everyone gathered around and listened to on the bus because he had done so much in the game and in life.

“Earl Lloyd was the first Black man to sit on an NBA bench in a suit and tie in a leadership role. He was the first Black assistant NBA coach, the first Black head coach who was not a (current) player, and going back to when he restarted his playing career after completing his military service, Earl Lloyd was the first Black player to be a member of a NBA championship team with the Syracuse Nationals in 1955. So, Earl Lloyd was much more than a footnote in history and his legacy certainly still matters today.”

Scott spoke during the afternoon of Nov. 9, just minutes before he was preparing to turn his attention to the Detroit Lions football game against the Washington Commanders. Largely due to the influence that Lloyd had on Scott’s life — including the time Scott spent as a Pistons player (1961-1967) and as the Pistons’ assistant and head coach (1972-1976) — Scott, a native of Philadelphia, developed a genuine love for Detroit, which extends to all of Detroit’s sports teams.

Like most Lions fans, Scott is hoping that this will be the season that the Lions finally bring Detroit a Super Bowl championship that would end a world championship drought for Detroit’s professional football team that began before Scott came to Detroit as Pistons player. But Scott also revealed that if all of Earl Lloyd’s recommendations had been acted upon during Lloyd’s years as a Pistons scout during the 1960s, that the franchise may have won a world championship in downtown Detroit — at Cobo Arena — long before the “Bad Boys” Pistons teams that won back-to-back NBA championships in 1989 and 1990 while playing home games at The Palace of Auburn Hills.

“Earl Lloyd wanted the Pistons to draft Willis Reed out of Grambling State University and Earl Monroe from Winston Salem State University — two of the all-time greats and future Hall of Famers who were stars on championship New York Knicks teams during the early 1970s (1970 and 1973),” Scott explained. “Reed, the captain of the Knicks, was not selected until the second round by New York in 1964, and Monroe (acquired by New York in 1971) was picked second overall by the Baltimore Bullets in 1967 when the Pistons had the first pick in the draft (used to draft Jimmy Walker from Providence College). Despite the fact that Reed and Monroe were available to the Pistons, this was a time when many teams were still critical of the talent at HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges & Universities).

“But Earl Lloyd was aware of that talent and he represented HBCUs when he was selected as a player (ninth round, 100th overall pick) in the 1950 NBA Draft. So, he knew those guys could play in the NBA because he had done it and he helped to pave the way for young men that became stars in the league, even though he wasn’t allowed to bring some of those great stars to the Pistons at that time.”

Scott says if Lloyd had his way, the Pistons’ opening night lineup in 1967 could have featured four future Hall of Famers with Reed and Monroe being joined by Pistons legend Dave Bing and the pride of Detroit’s Austin High School Dave DeBusschere, who also was a key member of two New York championship teams after the Knicks acquired him from the Pistons in a trade on Dec. 19, 1968.

“If we’re talking starting fives, that potential lineup has to be in the conversation as one of the greatest lineups,” stated Scott, who said he would have loved to have been a support player on a Pistons team led by those four superstars. “With all of that talent, to use a music analogy, it would have been like having one of the great big bands entertaining the fans at Cobo on a nightly basis, instead of an ordinary quartet or quintet.”

And while Lloyd may not have been able to get every player he wanted for the Pistons, the 87-year-old Scott says there is no doubt that his late mentor will forever be a champion to many.

“Earl Lloyd brought me through the progressions of life, in terms of showing me how to be a good player, coach, businessman, and most importantly a good person and husband,” said Scott, who with his mentor’s blessing, succeeded Lloyd as the Pistons head coach after the seventh game of the 1972-73 season, enroute to Scott making his own history as the first Black person to be named NBA Coach of the Year following the 1973-74 season when the Pistons posted a 52-30 record. “And in the same ways Earl Lloyd helped me, he helped many other people. I just read an article about my former Pistons captain when I played, Bailey Howell, who came from Starkville, Mississippi, where Blacks and whites were separated during the Jim Crow era, and Bailey Howell talked about how Earl Lloyd welcomed him warmly to the Pistons.

“We’re talking about someone who served his country, the NBA and humanity well. Earl Lloyd was just that guy.”

Scott Talley is a native Detroiter, a proud product of Detroit Public Schools and a lifelong lover of Detroit culture in its diverse forms. In his second tour with the Free Press, which he grew up reading as a child, he is excited and humbled to cover the city’s neighborhoods and the many interesting people who define its various communities. Contact him at stalley@freepress.com or follow him on Twitter @STalleyfreep. Read more of Scott’s stories at www.freep.com/mosaic/detroit-is/. Please help us grow great community-focused journalism by becoming a subscriber.