The NBA has several rites of passage in each season: the All-Star Break, the playoffs, the NBA Finals, MVP awards and drafting and free agent season. Nestled among all of them, hidden but no less regular, is the annual head shake of disgust over teams that are tanking for high lottery picks in the upcoming draft.

The story is no different this year. Perhaps because of global warming or some other oddity, Tanking Season has arrived sooner than normal, before the All-Star Game, even. But it’s here.

Last night as the Blazer’s Edge Staff was discussing the game between the Portland Trail Blazers and Utah Jazz, we surmised that programming an AI coach for Utah would be fairly simple at this point:

20 If X > 20, then OUT, GOTO Injury List

Along with the angst over the tanking issue come suggestions for how to fix it. We’ve published several ourselves. Some have been innovative, others practical. All of them try to solve the basic puzzle confronting the league: How do you keep the draft as a mechanism to promote competitive balance without member franchises scheming to take advantage of that mechanism?

Every time the NBA fixes one side of that equation—smoothing out the odds, for instance, so there’s less incentive to finish low—the other side goes haywire. Less-needy teams, some in dire straits for only a season, get the best players. So we weigh the odds towards the worst records. Then tanking goes through the roof. So we even out the odds again and Dallas gets Cooper Flagg. It’s an infernal see-saw that won’t balance.

If you can bear one more, though, here is a solution that would probably fix the process, at least as much as it can be fixed. Along the way to the answer, we’ll address a couple of commonly-proposed alternative solutions and show why they won’t work in today’s NBA.

Let’s tackle the “why it won’t work” part first.

No, You Can’t Just Even Out the Odds

SHIFTING THE LOCATION, NOT THE TANKING

This should be copied, clipped, and reprinted to every media member, radio host, former player, and analyst across the basketball landscape. There’s a misconception that going back to the original lottery system where every non-playoffs team has equal odds for high picks would eliminate tanking. If losing more doesn’t get you more, nobody will tank! Some people think the cost in fairness to bad and/or less-advantaged teams would be worth it.

It won’t work. Evening the odds won’t stop tanking. It’ll just shift where it occurs.

For all its flaws, the current system has one advantage. There’s a bright, clear line between playoffs teams who head to the postseason and lottery participants who don’t. Anyone who is tanking is bad already. With the odds of leaping to the top spot at less than one percent for the 14th participant in the lottery, approximately zero teams are saying, “Let’s miss the playoffs so we can get a 1-in-200 shot at the next superstar.” That leaves the postseason, and the competition for it, fairly clean.

Once you even those odds, you’ve muddied the waters in the exact spot they need to be clearest. Now teams face a legitimate question: Do we want to be the 8th seed and go out in the first round or do we want to have as good of a shot as anybody else at an ultra-high pick?

The optics are horrible. Even raising the question is damaging. People already say the NBA regular season doesn’t matter…or at least doesn’t matter enough. Imagine seeing teams opting out of the playoffs, as if they didn’t matter either. Imagine lesser teams backing into the first round as a result, making half of the opening series of the playoffs a silly exercise.

If you think tanking for the last spot in the conference is a public relations nightmare, imagine teams tanking for the 9th spot instead.

“Play-In Tournament? After you!”

“No, please, I insist.”

PA Announcer: Now starting for the home team in this winner-takes-all contest, the Assistant Athletic Trainer!

TV Analyst: Signing him to a two-way contract at the last second was a brilliant decision, Jim!

Play-by-Play Guy: Wait a minute, Carl. Look who’s taking off his warm-ups! It’s the Sno-Cone Vendor!!!

TV Analyst: What a move! The home team really got outplayed here.

THE REST OF THE LEAGUE ISN’T BALANCED EITHER

Beyond that, the NBA needs the competitive balance correction that the draft provides, no matter how annoying it is, no matter how quickly some analysts want to dismiss it.

There are three main ways for NBA teams to acquire talent: free agency, trades, and the draft.

Trades are theoretically equal-access for all. They’re fairly egalitarian compared to the other two. But they suffer from two faults:

You need to have talent to trade for talent. If you can’t acquire talent via the draft or free agency, you won’t have anything to trade. It’s worth noting that teams with less talent rely on trading their draft picks—made disproportionately valuable by a weighted lottery system—in order to execute major deals.Stars and superstars are rarely available on the trade market anyway. And when they are, they have leverage over where they go. This is especially true for superstars. When the Trail Blazers or Jazz can trade for LeBron James (even theoretically) with a straight face, you can claim the trade market is equal. Until then, it’s kinda not.

Free agency is even less balanced than trades, for the same reason we just mentioned. The only thing less likely than a small-market, fairly-bad team trading for LeBron James is the idea that he’d voluntarily sign there. That’s true even if they clear cap space to offer him a max contract. The money of disadvantaged teams doesn’t spend on the open market like the money of advantaged teams.

That just leaves the draft. And here come fans and experts, up in arms, wanting to make sure that the NBA Draft is 100% balanced, 100% fair, 100% good for the image and equity of the sport when it’s literally the only mechanism that allows 75% of the league to compete on semi-equal footing with the privileged 25%. People want to fix the draft without even beginning to address the inequities in the other avenues of improvement.

It’s a bit like the (no doubt fine) residents of Malibu Beach with their oceanfront mansions saying, “If those commoners want a house in our neighborhood, why don’t they just purchase one? I don’t understand the problem. They pay $2000 in taxes each year and I pay $2000 in taxes too. The system is balanced out. They should have enough money left over. Let them eat sun-porches!”

By the way, if you don’t believe me on the inequity thing, check this out.

Since the year 2000, 50 teams have participated in the NBA Finals. That’s two each year for 25 years.

Let’s separate out eight of them: the Miami Heat, Orlando Magic, San Antonio Spurs, Houston Rockets, Dallas Mavericks, Los Angeles Lakers, New York Knicks, and Boston Celtics. Those eight teams fall into one of two categories. They’re either considered marquee destinations by market size and/or NBA lore or they operate in a state with no income taxes on player salaries, providing a heavy boost to take-home pay.

Those eight teams account for 27 of the 50 NBA Finals appearances in the last 25 years. Put another way, if you’re on one of those eight teams, you can expect an average of 3.4 Finals appearances in that span. And that’s WITH the Knicks and Rockets providing zero, dragging the average down.

The other 22 teams in the league account for 23 of 50 appearances. If you’re with one of those franchises, your Finals appearances average goes down to 1.

Teams in the privileged group of eight are 3.4 times more likely—340% more likely—to make the NBA Finals than everybody else. And this is in an era known for its parity.

By the way, in that other group, the Cleveland Cavaliers and Golden State Warriors account for 11 appearances, leaving just 12 for the other 20 teams combined. Basically we can say you’re either a marquee team, play in a no-tax state, or you have LeBron or Steph Curry on your roster. Otherwise your NBA Finals appearance average goes down to 0.6. A team in the Privileged Eight is 6 times more likely to see the Finals than you.

Hold on. We’re not done.

Do you know how the Warriors and Cavaliers got Steph and LeBron? They drafted them. If you count LeBron returning to Cleveland the second time as them having a player they originally selected, just FOUR non-marquee, non-tax NBA Finals participants in the last 25 years can claim to have gotten there without their leading player being a star that they, themselves, drafted. That’s about an 8% success rate in the non-marquee, we-pay-state-taxes group.

Taking away the aid that struggling teams get through the draft won’t balance the league, it’ll cement the imbalance that already exists.

If we were to develop complex rules and compensations based on trades and free-agent signings that docked teams draft positions when they made a big move—viewing the ecosystem as a whole organism instead of fixing one part and leaving the others unaddressed—we might have a chance. That’s probably not possible overall and it’s certainly not desirable from an ease-of-access and public understanding standpoint.

Failing that, if you’re not going to balance out trade and free agent advantages, don’t claim you’re fixing the league by balancing out the draft.

No, The Wheel Won’t Work Either

Whenever we discuss these matters, someone always brings up The Wheel, a system published back in 2013 that was reportedly circulated in NBA circles after being invented by a team employee.

The Wheel eliminates randomness in the draft. It rotates all 30 franchises through the order on a clock-like basis. In 2026 it’s one team, in 2027 another, regardless of record or performance. In 2056 the cycle will repeat. No fuss. No muss. We know exactly where picks will fall and when. It’s all parceled out equally.

Except if we know where picks will fall, so do players and agents. Nothing says a player has to enter a particular draft. With NIL money flowing through the college ranks like water now, it’d be easy for a star to extend their NCAA career another season or two, still making more take-home-pay than they’ve ever dreamed. If you’re going to be picked first by the Jazz this summer, why not delay a season and get scooped up by the Knicks?

Advocating for The Wheel at this point is akin to claiming that there’s no real difference between the top pick in the Zaccharie Risacher draft and the following year when Victor Wembanyama came to the league. They’re both first-overall picks, so they’re both equal, right? And if not, no worries. I’m sure you can make up for it in…checks notes…thirty years. Good luck, Utah.

Nothing will eliminate tanking entirely. Any time you devise a system, people will try to game it to their advantage.

If you want to have the least amount of tanking happening the least amount of times, the solution is actually pretty simple. Keep the current system intact but make the odds look a little more like a bell curve than a bottom-heavy stairstep.

The first priority is to keep the odds of getting high picks for the best teams in the lottery low. That’s necessary to eliminate the “dropping out of the playoffs to get ping pong balls” fiasco we mentioned above.

But that doesn’t mean that odds have to increase automatically and progressively until you get to the teams with the worst record. All those teams need is a good chance to get a high pick. They don’t have to have the best chance. That makes a difference.

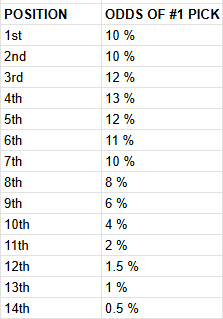

Currently the worst three teams in the league have 14% chances at the first-overall pick. That drops to 12.5%, 10.0%, and so on.

The 9th-14th positions aren’t changed much from where they are in the current system. If you’re close to the playoffs, it doesn’t make sense to drop all the way to the 8th-worst record in the league to get a significant shot at a high pick, one that’s still lower than 7 other teams. But if you are bad and you’re thinking about tanking, you’re threading a needle trying to find the best position. Finishing 8th-worst is almost the same as finishing worst. Finishing 7th is exactly the same odds.

It’s easy to try and tank for the worst record in the league. How do you strategize to end up 4th-worst, where the best odds are? You might actually have to win some games if you try.

After a certain point, tanking just doesn’t make sense anymore. It will even be counterproductive to lose too much. But the percentages lost from going too far down the scale aren’t so drastic that you don’t get help no matter where you finish.

You can parcel out the odds slightly differently—make the worst team have 9% odds and the second-worst 11% if you want—but you get the idea. Make the reward curve widen out at some point besides the bottom without shifting the overall rewards too much towards the top. Bad teams will still be bad, but there’s a limit. And somewhere in there exists an incentive for even them to win sometimes.

In most other solutions to fixing the draft, I’ve offered some kind of limitation on the number of times a team can win a high pick in a given span. I believe that’s still an important part of the system, even this one. If your record is bad, you should earn the spot you would naturally get in the order no matter what. But if you’ve already received a top overall pick, you should be ineligible for promotion for “X” years after that pick. Details can be worked out later, but the basic idea is, no team should get the first AND a second AND another first because of lucky bounces.

Obviously this would apply only to a team’s organic picks, not any picks traded for. This is an important, and under-addressed, corrective to the “helping the disadvantaged” theorem. We don’t want random luck advantages to go too far just like we don’t want any other off-the-court advantages to do so.

No solution is going to be perfect. It’s easy to shoot down proposed new systems based on flaws without realizing that the current system has huge flaws too, yet we live with those. The question isn’t whether a solution is going to solve everything. It won’t. We have to ask whether a proposal will address some of the current flaws without making something else worse or completely breaking the system in a different way.

This solution has the benefit of being usable. The system is already in place! The changes aren’t huge. It’s doing what the league has been doing for years: messing with the weighted odds. But instead of weighting them towards one end of the see-saw or the other, you put them in the middle. Everybody who’s losing gets some help, but nobody can tell for sure whether losing or winning will get them a clear advantage until the literal final week of the season, when most everybody is looking past tanking anyway in anticipation of the playoffs. If you look at a game in February, winning it might be as good as losing it.

That’s not exactly the, “Win everything you can at all costs!” mentality we favor in sports, but it’s the best chance we have at addressing the problem without creating even bigger ones in other parts of the NBA ecosystem.

IF YOU WANT TO HELP send kids in need to see the Blazers play on March 10th, this is the LAST WEEKEND for donations. Click through this link to get to the Blazers’ donation site. Every ticket you buy sends one more person to the Moda Center to see the team play!