It was never Jason Collins’ intention to be a spokesperson or the leader of a cause. He just wanted to live a life that was open and honest, a life untangled from the usual excuses and dodges that are in the playbook when you’re in the closet.

But when you emerge as the first active, openly gay player in NBA history, as Collins did in 2013, you can’t not be a spokesperson. One of the constants in the evolution of the openly gay athlete in the major North American men’s professional sports leagues — the NBA, NFL, MLB, NHL and MLS — is that everyone who comes out is providing a for-free blueprint for those who dare to be next.

It’s different in women’s professional sports, where there’s a well-chronicled history of out players and generally high support from the leagues and their fans. In the men’s leagues, progress has been slow and tentative. So, yes, Collins shares his experiences. His words are important. His story is important.

But the timing for this interview wasn’t good. Collins and longtime boyfriend Brunson Green were to be married in two weeks — Memorial Day weekend — and there was still so much to do. Is the tent all set? The food? The DJ?

“And all that other stuff that goes into having a fun and enjoyable weekend,” Collins said, speaking from Austin, Texas, over the phone. “I would have called earlier, but I was going over the wedding playlist.”

And then, just like that, something happened that revealed a subtle difference between being closeted and being comfortably out. With the conversation shifted to the wedding, Collins was asked if his old college roommate from Stanford, Joe Kennedy, a former congressman from Massachusetts, would be in attendance.

“I think Joe’s coming,” Collins said. He paused. And then, speaking not into the phone but apparently to somebody else, said, “Brunce, are Joe and Lauren coming to the wedding?”

“Brunce” is Brunson Green, of course. Had Collins been doing a phone interview during his early years in the NBA — he broke in with the New Jersey Nets in 2001 — he might have thought twice before redirecting a question to a buddy, as in a male friend, who happened to be in the room. And even if he had, it’s doubtful he would have dropped in a chummy nickname. The guardrails would have been up, as they are for many in the closet. Always trying to be one step ahead of the posse, always covering up tracks.

Now it is 2025, some 12 years after Collins, who was technically a free agent, came out via an essay he wrote for Sports Illustrated. (He reemerged in the NBA months later with the Brooklyn Nets, with whom he closed out his career.) The former NBA big man, 46, is now married to a current Hollywood big shot, the 57-year-old Green. Among his other accomplishments, Green produced the 2011 film “The Help,” which earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture.

Yep, they’re hitched. The tent, the food, the DJ, all made it to the wedding. As did Joe and Lauren Kennedy.

Again, Collins didn’t get married for the headlines. He married Green because he loves the guy. But as Kennedy noted in a phone interview, “If you read the Sports Illustrated piece — I have a copy signed by Jason hanging in my house — he said he wasn’t (coming out) to make a statement, but that he was willing to raise his hand and say, ‘I’m here.’”

Jason Collins speaks with the media before a game in Denver in 2014. (Justin Edmonds / Getty Images)

In the ongoing story of the out athlete, it’s the “I’m here” that contributes to the blueprint for other past, present and even future pros mulling a big announcement. While the roll call of players who’ve come out over the last two decades isn’t extensive, each announcement makes a mark.

It’s not just other athletes who are paying attention. Ryan O’Callaghan, who is among several former NFL players to come out in recent years, cites an email he received from a man who had struggled with his son’s coming-out news.

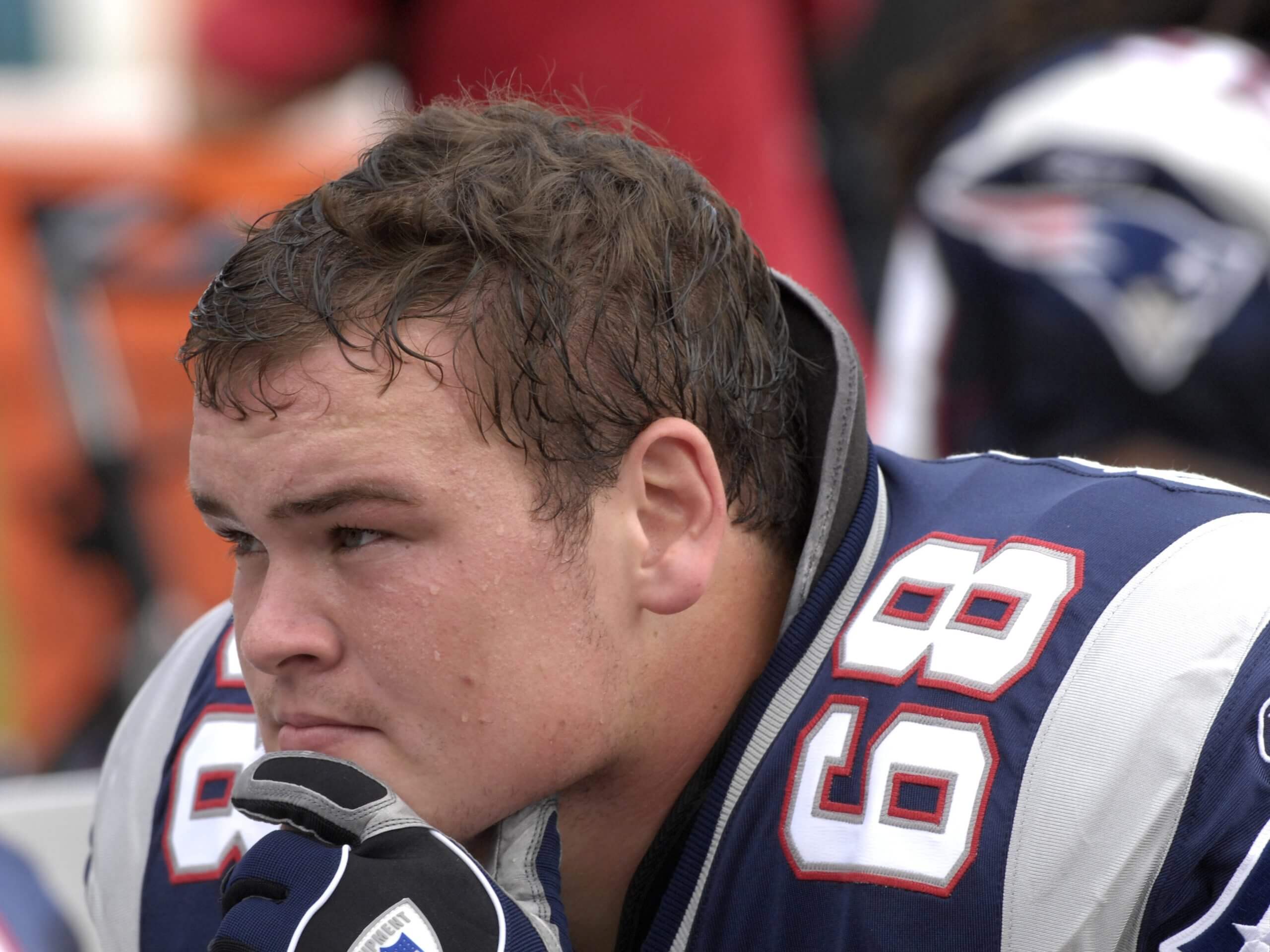

“He had disowned his son,” said O’Callaghan, 41, a former offensive tackle who came out in 2017, seven years after playing parts of four seasons with the New England Patriots and Kansas City Chiefs. “In his email, he said my story made him reconsider the position he had taken, and to reconnect with his son.”

Coming-out stories can also inspire a gay athlete’s teammates to rise to the occasion, as American soccer player Robbie Rogers points out. Rogers was effectively retired when he delivered his news in early 2013 while living in the United Kingdom, but he then returned to the United States to play for the Los Angeles Galaxy of MLS. He knew he had been accepted by his Galaxy teammates the day he walked into the locker room and saw a message posted on the bulletin board by veteran captain Landon Donovan.

Team dinner this weekend. Don’t bring your husbands, wives, boyfriends or girlfriends.

With that one message, Donovan was treating Rogers like one of the guys. No speeches, no attaboys. Just a bro-ey invite for a players-only dinner.

“It’s not like Landon was part of some DEI committee who was told what to say,” Rogers said. “He just naturally wrote that. I was, like, oh, the world really changes.”

The way Rogers saw it, “Landon was just being Landon. It was something I never thought I’d see in the locker room. I’ve not shared this too much, but it was a really cool moment.”

Rogers, 38, has been married since 2017 to producer Greg Berlanti. They have two children: Caleb, 9, and Mia, 6. Rogers and Berlanti are also in business together, with Berlanti serving as executive producer and Rogers as producer of the television series “All American,” which is entering its eighth season. Rogers was executive producer of the gay-themed miniseries “Fellow Travelers,” which won a Peabody Award and garnered Golden Globe and Emmy nominations, and he is a producer of the documentary “The Last Guest of the Holloway Motel,” which premieres at the Tribeca Film Festival on Sunday.

Robbie Rogers and Greg Berlanti, shown posing with their children, work together as producers for the television series “All American.” (Courtesy of Robbie Rogers)

To whatever extent Rogers has gone Hollywood, he understands the impact of his decision to come out. He listens. He speaks. He offers advice.

“I would say find someone that can just listen to you talk,” Rogers said. “Someone who can help get your thoughts together and get whatever you’re dealing with out of your head. It can be such a lonely experience if you can’t put words to what you’re feeling.”

Collins said he took note of Rogers’ coming-out news as he was preparing to step out of his own closet.

“At the time that I did it, Robbie was out,” Collins said. “So I was thinking that you could look at his example, look at my example, that it was possible to do it. (I was) hoping that there would be more players continuing to lead the way regarding this conversation.”

But, Collins said, “I don’t know if disappointed would be the word. I would always try to spin things in the way of there’s work to be done.”

Ex-professional athletes have been coming out for decades. Dave Kopay, a running back who played in the NFL from 1964 to 1972, came out in 1975. The late Billy Bean, an outfielder with the Detroit Tigers, Los Angeles Dodgers and San Diego Padres from 1987 to 1995, came out in 2003.

John Amaechi, who broke into the NBA during the 1995-96 season with the Cleveland Cavaliers and later played for the Orlando Magic and Utah Jazz, came out in 2007. The list goes on and on, including these history-making announcements:

• In 2021, Carl Nassib became the first active NFL player to come out. The 6-foot-7, 275-pound defensive end played for the Las Vegas Raiders and Tampa Bay Buccaneers before retiring.

• In 2014, University of Missouri defensive end Michael Sam came out in advance of the NFL Draft and was selected in the seventh round by the St. Louis Rams. Though Sam never played a regular-season game in the NFL — he appeared in preseason games and served practice-squad stints with the Rams and Dallas Cowboys — his coming-out announcement remains a watershed moment in the LGBTQ+ community.

• Luke Prokop is the first openly gay hockey player to be under contract to an NHL team, with his announcement taking place about a year after being selected by the Nashville Predators with the 73rd pick in the 2020 draft. Prokop has yet to appear in the NHL. He played for the AHL Milwaukee Admirals this past season.

Professional athletes come out in many different ways. In 2012, some five years before O’Callaghan came out publicly, and after spending all of 2011 on the injured reserve list with the Chiefs, he had a private conversation with then-Chiefs general manager Scott Pioli, who over the years has emerged as a five-star ally of the LGBTQ+ community.

“Ryan came into my office, he seemed really upset, really anxious,” Pioli said. “He said, ‘I have something to tell you.’ And he couldn’t get the words out, so now I’m getting nervous, like maybe he’s done something really bad.”

O’Callaghan finally said, “I’m gay.” Pioli remembers his response as being, “OK, what else?”

Ryan O’Callaghan’s public coming out took place in 2017 via a story for Outsports.com. “I was surprised how big a story it was at the time,” he said. (Al Messerschmidt / Getty Images)

Years later, O’Callaghan said he expected Pioli to be upset or disappointed. Looking back on it, Pioli said the only thing that upset him was the way the meeting ended.

“We got up, I’m sitting behind my desk, he’s sitting in front of my desk, he was emotional, I was emotional,” Pioli said. “When he went to leave, I was walking in to hug him and he put out his hand to shake my hand. It was always handshake and a hug, but now he was giving me the distance of a handshake. And I gotta tell you, that broke my heart. I said, ‘What are you doing? We hug.’”

They hugged. They did, after all, have a long history together: Pioli was vice president of player personnel for the Patriots when O’Callaghan broke into the NFL with New England, and they were later reunited in Kansas City.

O’Callaghan’s public coming out took place in 2017 via a story for Outsports.com written by Cyd Zeigler. The two later collaborated on a book, “My Life on the Line: How the NFL Damn Near Killed Me and Ended Up Saving My Life,” which also deals with O’Callaghan’s battle to cleanse himself from reliance on prescription painkillers.

“I was surprised how big a story it was at the time,” O’Callaghan said of his coming-out news. “I was on Dan Patrick and all these other shows. Thankfully, Cyd acted as a stand-in publicist.”

For Rogers, it was a heartfelt post on his website. “And then I turned my phone and computer off,” Rogers said. “A few hours later, I was with some friends and they said, ‘You should look at that thing you posted.’”

Rogers looked. People were reaching out. Lots of them.

“And reporters were calling me and my agent,” Rogers said. “I was in London. Back home in California, my mom said a reporter came to the house.”

Collins wrote the essay for Sports Illustrated, which was posted on April 29, 2013. It was the cover story for the magazine’s May 6 print edition.

“We knew it was going to be online at 11 a.m. Eastern time,” Collins said. “I was living in Los Angeles at the time. There were people I felt should hear it from me first, so that weekend, there were a lot of phone calls that were being made.”

About an hour before the story appeared, Collins was on the phone with then-NBA commissioner David Stern and then-deputy commissioner Adam Silver.

“They were extremely supportive,” Collins said. “I couldn’t have done what I did without seeing what the leadership of the NBA was doing. When I first entered the NBA in 2001, players were allowed to use homophobic language without consequences. That changed in the mid-to-late 2000s. There started to be fines for using homophobic language. When I saw those fines being levied, especially with a minimum fine of $50,000 being implemented, that to me was a sign that NBA leadership has my back.”

The homophobic remarks continue here and there, in all sports. One might go so far as to say snarky, inappropriate language has made a comeback in today’s politically charged world, and not just in relation to coming-out announcements and the transgender community. Now that legalized gambling is part of the sports experience, the crowing is getting louder and nastier — from the stands and on social media.

Looking back on his coming-out experience, Rogers said, “I heard people say, ‘Why do you have to tell everyone,’ and ‘Why can’t you just live your life,’ or ‘You don’t belong in sports.’ But those aren’t downsides. That’s just the way the world works.”

So, why did Rogers have to tell everyone?

“I kind of felt I was doing something a bit more selfish,” he said. “It sounds cliché, but I was setting myself free.”

(Illustration: Kelsea Petersen / The Athletic; AAron Ontiveroz / Getty, Sam Forencich / Getty, Georgoe Gojkovich / Getty)