The Oakland Raiders left their mark on New Orleans at Super Bowl XV.

If ever an NFL team was made to enjoy the temptations and trappings of the city’s fabled French Quarter, it was the Raiders.

Super Bowl XV was played five days after the Iran hostage crisis ended, and for the first time, the NFL used the game’s global platform to make a political statement.

The league honored the 52 American hostages released after 444 days in captivity with a conspicuous tribute: An 80-foot-by-30-foot yellow bow was displayed on the side of the Superdome for everyone to see. Behind the $4,500 bow, a pair of 180-foot-long ribbons draped down the side of the stadium, which was illuminated at night by the Dome’s new exterior lighting system.

Fans were given miniature yellow bows as they entered the stadium for the game, and cheerleaders for both the Oakland Raiders and Philadelphia Eagles carried yellow streamers with their pompons. All players in the game wore a symbolic yellow stripe on the back of their helmets in a show of support.

A moment of silence was observed during pregame to give thanks for the safe return of the hostages, then the Southern University band played the national anthem, following by a version of “Tie a Yellow Ribbon.”

This was the fifth Super Bowl here in 12 years, and city officials were becoming experts at staging the game. New Orleans was awarded the game at the 1979 NFL owners’ meetings in Honolulu, where the city won the bid over heated competition from Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Pasadena and Seattle.

An estimated 70,000 visitors came to New Orleans for the week, generating a $40 million windfall for the city, said Ed McNeill, the director of the New Orleans Tourist Commission. The city’s 22,000 hotel rooms were sold out and more than 3,000 private aircraft reportedly made their way through the area’s regional airports. “Mardi Gras is a people event,” McNeill said. “Super Bowl is an executive event.”

By this time, the Super Bowl had started to morph into a weeklong corporate affair — built around a three-hour football game. The parties were more lavish than ever. NBC threw an extravagant dance cruise for sponsors and team owners on the S.S. President Steamboat. Barbara Eden, Robert Conrad and Lee Majors were among the celebrities in attendance. The NFL bash on Friday night at The Rivergate featured the Preservation Hall Jazz Band and the Count Basie and Doc Severinsen orchestras. Among the guests were Joe DiMaggio, Fred MacMurray and Kentucky Gov. John Y. Brown and his wife Phyllis George. The dining menu for one corporate party at the Fairmont Hotel featured smoked eel, rainbow trout, quail eggs and lobster appetizers with a Le Delice de Canard Sauvage (Aux Cinq Poivres) entrée.

The game pitted a pair of teams from gritty, blue-collar towns that embraced the underdog role. As one Times-Picayune writer put it, “Both squads resembled football’s version of the Foreign Legion with a collection of has-beens and castoffs.”

The Eagles were making their first postseason appearance since 1960. They’d struggled for decades under dysfunctional management and ownership but had found new life under fifth-year coach Dick Vermeil. The Eagles featured a collection of veterans like Woody Peoples (37), Claude Humphrey (36) and Bill Bergey (35), who were in the August of their careers.

Despite their relative lack of experience in big games, the Eagles were installed as 3-point favorites on the strength of their 12-4 regular season record, which included a 10-7 win over the Raiders and an authoritative win over the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC championship game.

The Raiders were comfortable in the underdog role. They’d earned their way to New Orleans upsetting the Oilers, Browns and Chargers via the wild card route. The Raiders described themselves as “the halfway house of the NFL” and were known as collection of rebels and ragamuffins who took their cues from iconoclastic owner Al Davis.

While the rosters were similar, the teams’ approaches to the game differed.

During the week leading up to Super Bowl XV, the Raiders took to New Orleans’ world-renowned nightlife like fish to water.

Meanwhile, their opponents, the Philadelphia Eagles largely behaved themselves under the iron hand of Vermeil, a strict disciplinarian.

When the teams landed in New Orleans on the Monday before the game, Vermeil took his team directly to practice. Raiders coach Tom Flores, meanwhile, turned his team loose. He gave them an 11 p.m. curfew starting on Tuesday, but otherwise allowed his team to enjoy New Orleans and all of its temptations.

“We cruised the French Quarter, but we didn’t see any Eagles,” Raiders quarterback Jim Plunkett said.

John Matuszak was seen by reporters in the French Quarter in the wee hours of morning overnight on Wednesday. The hulking 6-foot-8, 280-pound defensive end known as The Tooz was one of the biggest characters on the team, a man who once described himself as having “a 16-word vocabulary and 1,000 different grunts.”

Matuszak told Flores he simply was acting as a monitor to make sure that younger Raiders players did not stay out too late. Flores fined him $1,000, and that was the end of it.

A day later, Vermeil told reporters, “If I had a player who broke curfew, he’d be home by now.”

By kickoff on Sunday, the Raiders’ approach, however, proved to be the winning one. Oakland players were loose and confident. The Eagles were just the opposite: tight and jittery. Some believe they played their Super Bowl two weeks earlier in beating their longtime rivals, the Cowboys.

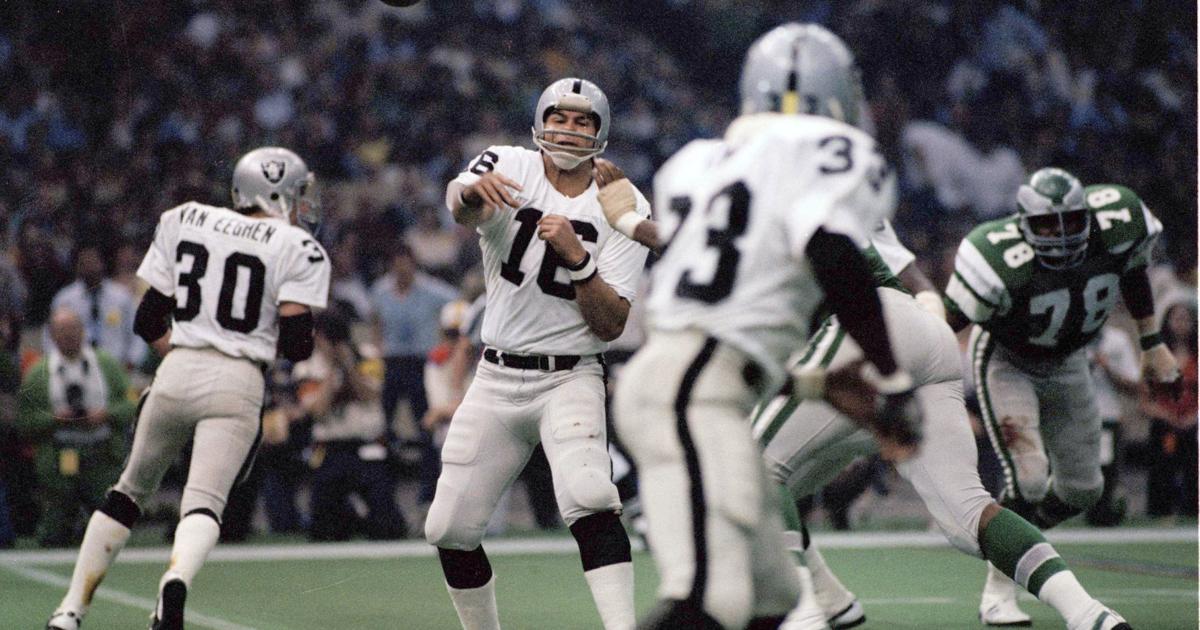

Whatever the reason, the Eagles stumbled out of the gate. On the game’s third play, Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworski tried to force a pass into tight coverage to tight end John Spagnola and Raiders linebacker Rod Martin stepped in front for an interception. Six plays later, Jim Plunkett hit Cliff Branch for a 2-yard touchdown pass.

Later in the quarter, Jaworski hit Rodney Parker for a 40-yard touchdown pass, but the play was nullified by an illegal motion penalty on Harold Carmichael. The Eagles punted and two plays later, on third-and-4 from the Raiders’ 20, Plunkett was forced from the pocket in a classic scramble drill. Running back Kenny King was supposed to be an outlet receiver, but he improved his route, got behind Herman Edwards and turned upfield. Plunkett hit him in stride, and King raced the final 60 yards untouched for on an 80-yard touchdown. From there, the shellshocked Eagles never recovered.

“The play is not designed for me to go all the way,” King said later. “I’m just supposed to go 6 yards and cut to the sideline. It was a fluke play. The defensive back came up to force, and I just turned it upfield.”

After cutting the lead to 14-3, the Eagles drove to the Raiders’ 11 just before halftime, but Jaworski missed an open Parker in the end zone and Tony Franklin’s 28-yard field goal try was blocked by Ted Hendricks. It was that kind of day for the Eagles and Parker, a New Orleans native who grew up, playing in youth leagues at Bunny Friend playground in the Desire neighborhood and once worked as an usher at Tulane Stadium for Super Bowl IV.

The halftime show was themed a “Mardi Festival” and featured a six-float Mardi Gras-style parade and performances by “Up with People” and Pete Fountain’s Half-Fast Walking Club.

In the second half, the Raiders continued their dominance. They extended their lead to 21-3 on Plunkett’s third touchdown pass, a 29-yarder that Branch retreated on and outfought New Orleans native Roynell Young for the wobbly, underthrown ball.

“That was a great individual effort,” Plunkett said. “He took the ball right out of the cornerback’s hands.”

From there, the offensive line and powerful running back Mark van Eeghen took over and the Raiders iced the game. The offensive line, which allowed eight sacks in the regular season loss to the Eagles, did not allow a sack this time and cleared the way for 117 rushing yards.

Meanwhile, the defense continued to shut down Wilbert Montgomery on the ground, limiting the Eagles star running back to 44 yards on 16 carries and a long run of 8 yards. Martin added a third interception, setting a Super Bowl record that still stands today.

“The Raiders dominated us and deserve to be the world champions,” Vermeil said. “Oakland was a better football team regardless of philosophy. There is not one way to do anything in this business. We got here under a pretty sound approach, and I’m not sure we get here using any other kind of approach.”

Plunkett was named the MVP after completing 13 of 21 passes for 261 yards and three touchdowns. It was the high point of his Cinderella story in Oakland. A year previously, he’d contemplated retirement. The 33-year-old journeyman was signed to be Dan Pastorini’s backup, but he was thrust into the starting lineup when Pastorini broke his leg in Week 6. Plunkett threw five interceptions in his starting debut that season but recovered and led the Raiders to wins in nine of their final 11 games.

“This is the greatest moment in my life as a pro football player,” he said.

All eyes were on the postgame trophy presentation, where NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle presented the Lombardi Trophy to Raiders owner Davis, who had sued the league for $160 million for not backing his intended relocation from Oakland to Los Angeles.

The two made nice, though.

“As the first wild-card team to win the Super Bowl, it’s a tremendous compliment to your organization because you had to win four postseason games,” Rozelle said.

The win capped a strong of four postseason triumphs as the underdog, making the Raiders the first wild card team to win the Super Bowl.

“When you look back at the glory of the Oakland Raiders, this was our finest hour,” Davis said.