The prospects for the 2025 New York Giants’ defense are a tale of two units. Up front, the Giants look like they could have a devastatingly effective pass rush: Dexter Lawrence, arguably the best pass-rushing interior lineman in the NFL; Brian Burns and Kayvon Thibodeaux on the edge, who together constituted one of the better pairs of edges in the league last season; and new supporting players Chauncey Gholston and Darius Alexander. Add to that the No. 3 draft pick, Abdul Carter, who has terrorized Giants’ offensive linemen thus far in training camp, and the possibility that the Giants’ pass rush could be the best in the NFL is not all that far-fetched.

It’s the back end of the defense that is the big question mark. Dru Phillips and Tyler Nubin had very good rookie seasons, but both of them did their best work in the box or the slot and neither was a ballhawk. On the outside, Deonte Banks was a disaster last season and hasn’t yet inspired confidence during training camp. Free agent signing Paulson Adebo is the new CB1, but he’s coming back from injury and tied for the league lead last season in frequency of being targeted (4.6 snaps per target). Jevon Holland, the new free safety, followed up his elite 2023 with a subpar 2024 in which he had a 111.3 passer rating against.

As we discussed a while back, defensive back performance is more variable and unpredictable from year to year than that of wide receivers, so it’s hard to say whether the 2025 Giants’ defensive backfield is going to be a strength or liability, even though there is talent on the roster.

The question I’d like to ask here is: How are a defense’s pass rush and coverage related in making a defense successful or not? First, let’s look at the quality of the pass rush of NFL teams to understand what makes for an effective pass rush. I’ll use the Pro Football Focus team pass rush grade for this purpose, but before I do, it’s worth understanding how PFF defines their pass rush grade:

To earn a positive grade, a rusher must win his block or affect the play beyond the base level of expectations on a given passing play. The quicker the win, the better the grade.

PFF’s grade is all about a pass rusher beating his blocker. Most of the attention for pass rushers comes from sacks, and indeed sacks are the most impactful pass rush outcomes in general. Sacks occur for various reasons, though, some of them having less to do with the rusher and more to do with the quarterback running into the sack, or holding the ball too long, etc. Not surprisingly, then, the correlation between team sacks and team pass rush grade (.41) is smaller than the correlation between pass rush grade and pressure percentage (.47). (Sacks and pressure rates were obtained from Pro Football Reference’s team defense rankings.) But just beating your man is enough to get a QB’s attention, even before the rusher gets close enough to record a pressure.

The figure below shows the individual team PFR pressure rates vs. PFF pass rush grades, with a few key teams identified. It’s easy to see that overall the relationship between the two is pretty good, but with two exceptions – the Philadephia Eagles and the Pittsburgh Steelers. Those happen to be PFF’s highest graded pass rushes for the 2024 season. Neither team, though, had an impressive pressure rate. Pittsburgh’s was comparable to that of the Giants, while Philadelphia’s was actually considerably less, in fact one of the lowest in the NFL. The same is true for sacks – the Eagles’ 41 sacks and the Steelers’ 40 were middle of the pack and fewer than the Giants’ 45 last season…yet the Steelers’ and Eagles’ PFF pass rush grades were much higher than the Giants’ (though the Giants’ grade was still one of the highest).

The possible importance of this is that when defensive linemen are consistently beating their blockers, it creates an expectation of pressure – for the quarterback as well as the offensive coordinator, whose play calling may be affected if he thinks that slow-developing plays may be doomed.

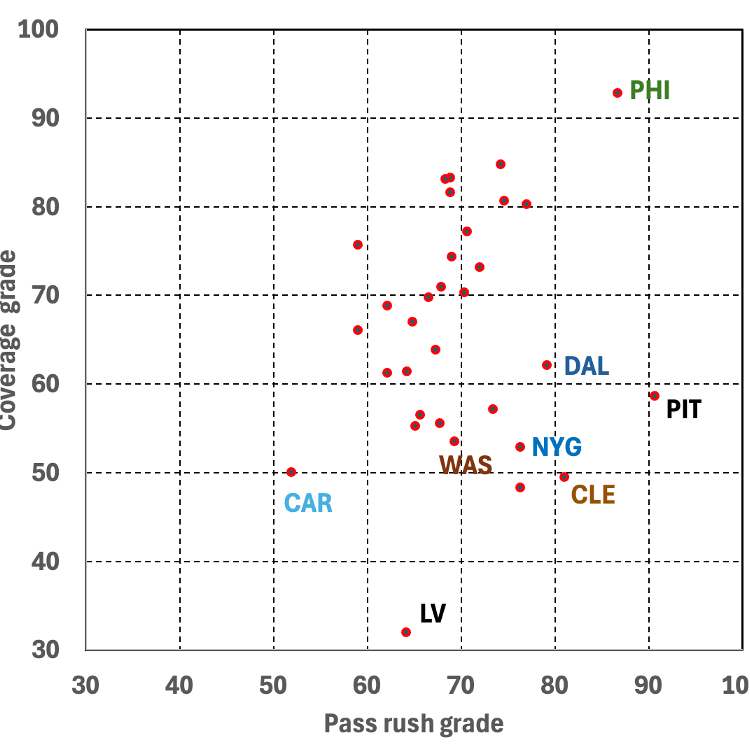

I mention this because of the plot below which shows the team PFF coverage grade vs. the pass rush grade for each team. The plot divides roughly into two branches:

a lower branch that contains teams whose PFF coverage grade was barely average or poor (roughly 63 or lower); for those teams there was no relationship between coverage grade and pass rush gradean upper branch in which there is a strong and statistically significant correlation (.72) between pass rush grade and coverage grade

This doesn’t prove anything, but here’s a hypothesis. There is no particular reason why teams’ defensive backfield quality should match their pass rush quality over a sample (the upper branch of the plot) as large as about half the teams in the league. Instead, perhaps there is a threshold of quality of pass coverage above which a team’s pass rush begins to have the desired effect: If defensive backs can stay with their receivers long enough for the pass rush to have an effect, then quarterbacks have to get rid of the ball before they see an open receiver.

Teams with poor pass coverage, on the other hand, do not benefit from a good pass rush because even when the quarterback sees a pass rusher bearing down, there is already an open receiver to get the ball to. In this scenario, the team coverage grade may only be partly due to the talent of the defensive backs – above some threshold, they are good enough to give the pass rush time to affect the quarterback. That in turn makes the defensive backs’ jobs easier, since they get to make plays before receivers get open more often, thus raising their coverage grade.

The Giants obviously did not have that last season. Their pass rush was plenty good enough, but the pass coverage was near the bottom of the league. The same was true for Dallas and Cleveland. All three finished with terrible records. Here are the Giants’ leading pass rushers compared to those of the Eagles and Steelers:

Courtesy of Pro Football Focus

Brian Burns, Kayvon Thibodeaux, and Dexter Lawrence had pass rush win rates every bit as good as the Eagles’ and Steelers’ best, yet only the Eagles had a dominating defense because they had good enough pass coverage to exploit what the players up front were doing:

Was every single Eagles defensive back in their regular rotation better in coverage than anyone the Giants and Steelers put out there other than Dru Phillips? Maybe so, according to the ranked PFF coverage grades above. Or maybe the Eagles’ DBs were just good enough to hang with their receivers long enough for the opposing QB to get happy feet anticipating the Eagles’ pass rush. The quarterback sees that the rusher has beat his man and knows he’ll have to get the pass off quickly, but the defensive backs are still in position to make plays, leading to a good coverage grade.

Maybe I’m selling the Eagles’ DBs short. Quinyon Mitchell and Cooper DeJean were top 40 draft picks, after all, and everyone thought they would be good NFL players. Reed Blankenship on the other hand was an undrafted free agent, and C.J. Gardner-Johnson’s 2024 coverage grade of 81.3 was significantly higher than anything he posted in New Orleans or Detroit.

So while we’re focusing a lot of attention on Abdul Carter and Jaxson Dart during training camp, the bigger question for the Giants this season may be whether the group of Paulson Adebo and Jevon Holland, along with Dru Phillips, Tyler Nubin and someone, whether Deonte Banks or Cor’Dale Flott, can just stay with their men long enough to allow the pass rushers to win against their blockers and force quarterbacks into hurried, ill-advised throws, with or without lots of sacks or even actual pressures. If they can, the Giants’ pass rush may well be devastating, even if its sack totals are not impressive. If not, things may not look much different from last season.