Editor’s Note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and performance through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

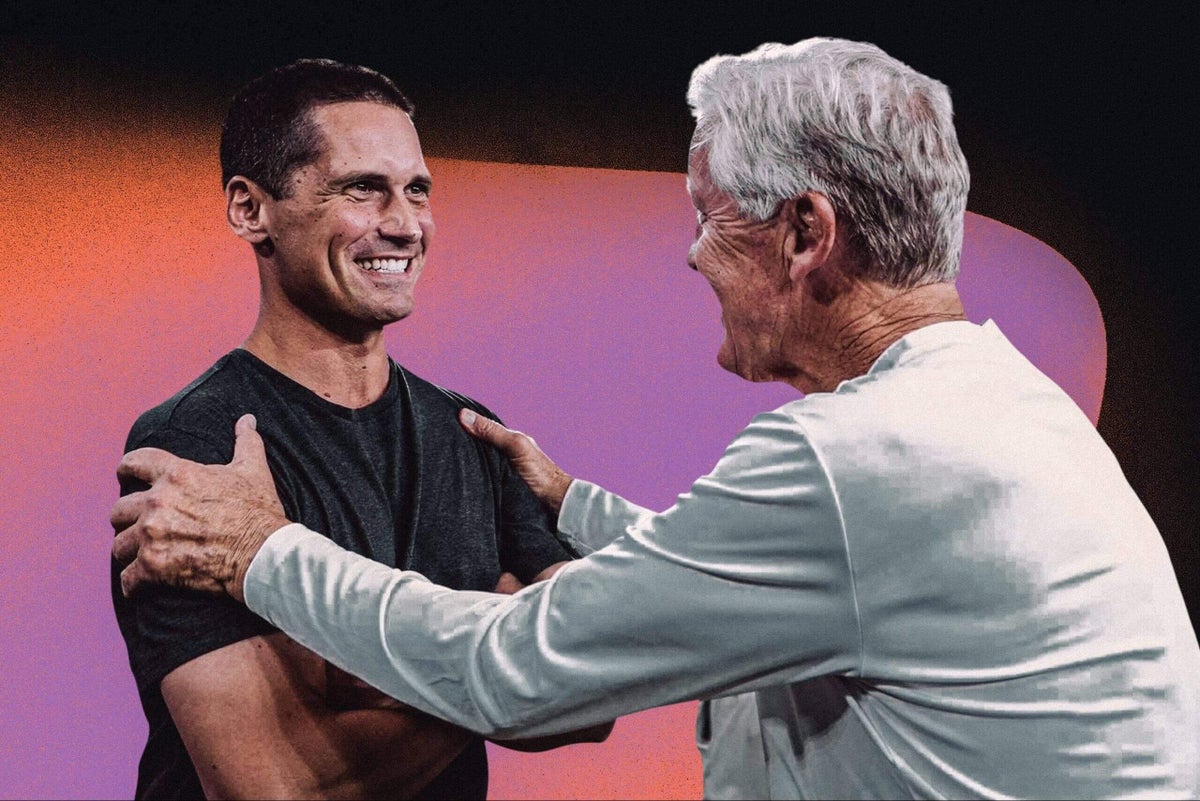

Ben Malcolmson was Pete Carroll’s right-hand man for 14 years, first with USC and then with the Seattle Seahawks. He is now the head of investor relations for a financial company.

One time during our early years together in Seattle, Pete Carroll spoke to several hundred employees at Microsoft. He hadn’t won the Super Bowl with the Seahawks yet, so in a sense, he was still trying to prove himself as an NFL head coach.

As Pete’s special assistant going back to his USC days, I went with him to his speaking events. By then, I was used to his enthusiasm and beliefs. But this one stuck with me.

During his talk that day, Pete asked the room: “How many people here have a philosophy for life or for work?”

Probably three-quarters of the room raised their hands. Then he asked: “How many people could tell me that philosophy in one line?” All but three or four arms bashfully went down. Pete called on one of the people who had kept their hand raised and had them share their philosophy in front of the whole room.

One of Pete’s favorite phrases is “You’ve got to know who you are,” but I remember going home from that event and thinking: Dang, I hear Pete say this stuff all the time — what if he asks me? I was in my mid-20s at the time. I realized I didn’t know my own philosophy, and that started me on a journey to figure out who I was.

Pete’s a philosopher at heart; he studied philosophy at the University of Pacific and often talked to me about concepts like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. His goal for every player, coach or person who works with him is to have them discover and articulate their true self.

Every year, after assistant coaches returned from vacation in February or March, Pete would meet with them one-on-one. They’d have to share with him: This is who I am. This is my philosophy, for coaching and for life. This is the lens I’m looking through.

The cool thing is that Pete actually has a loose process to help people figure that out. He made it so approachable that anyone can do it.

Simply take out a piece of paper or open the Notes app on your phone and start writing out how you show up to your family, friends and coworkers. What characteristics define you? How do you want to be described? What virtues resonate the most with you? It may seem daunting at first, but there’s nothing magical to it.

You have to write it out and then come back to it a few days later, rework it and write it again. It takes several iterations. Before long, you should have a list of a few traits and phrases. Some will rise to the top, and you’ll start to notice themes. It might happen all of a sudden or it might take days, but soon enough, you’ll have a moment where you go, Yes, this is me.

Pete didn’t want to over-engineer or micromanage the process. He understood that people’s minds are wired differently. For example, his personal philosophy is “Always compete.” Two words. His identity for his teams was “Great effort, great enthusiasm, great toughness, play smart.” It doesn’t have to be as short as two words, but he also didn’t want it to be a 10-page paper.

After going through this process, I landed on three main characteristics — kindness, joy, peace — and two ways I want people to describe me: a man of character and a great husband/father/friend. These identity affirmations and aspirations have been on the lock screen of my phone ever since.

That deep level of knowing who you are carries so much power because that’s where consistency comes from. When you live, work and operate consistently, excellence flows out of that.

I saw this firsthand with Pete. He is all about emotional regularity and consistency, and his consistency comes from knowing who he is. The temporal things that come and go — the wins and losses, the third-down failures, the turnovers — don’t carry as much weight.

The story I always think about: In February 2014, the Seahawks crushed Peyton Manning and the Denver Broncos, the best offense in the history of the NFL at the time, in the Super Bowl. On the Monday morning after the game, we were on the bus headed to the airport to fly back to Seattle. Pete was obviously happy, but he wasn’t jumping off the walls. He was just happy. Normal.

Not even a full year later, we lost the Super Bowl against the New England Patriots with a last-second interception on the 1-yard line. On the Monday morning after the game, we were on the bus headed to the airport again. We had just lost the Super Bowl in one of the most heartbreaking ways possible, if not the most heartbreaking way. Pete was obviously sad, but he wasn’t destroyed as though his life was over.

He was still Pete. He still had the same light in his eyes, the same countenance. And it’s because he did the work to know that his true self is never based on a win-loss record but on far greater things.

David Brooks wrote a book called “The Road to Character” that Pete strongly recommended to coaches and even some players. In that book, Brooks talks about eulogy virtues versus resume virtues. When someone gives a eulogy, they’re not reading someone’s resume or talking about their accomplishments — they’re talking about who that person truly was. Pete loved that. He was like, “We’ve got to get more people on the team to read this because this is what it’s really all about.”

I first started this process 10 or 15 years ago. It was the biggest way Pete impacted me, and what’s cool is I continue to live it out today, even applying it to my job now in finance. You may tweak it, but it’s not like you scrap it every year and create a new one. It’s such an empowering thing because you live from this amazing clarity: clarity of vision, clarity of purpose, clarity of identity.

It takes a little bit of work, but it’s beyond worth it. As Pete says to his teams, “Just be you, and that will always be enough.”

— As told to Jayson Jenks

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photo courtesy of Caden Briquelet)