Watching the seemingly endless rotation of Arch Manning Warby Parker advertisements this past weekend felt a little like watching a political ad after an election in which your candidate has lost.

The ads all seemed to be beamed from a more hopeful past when we were much more innocent, more naïve and definitely more deluded. It was a little like seeing someone wearing an ATLANTA FALCONS SUPER BOWL LI T-shirt.

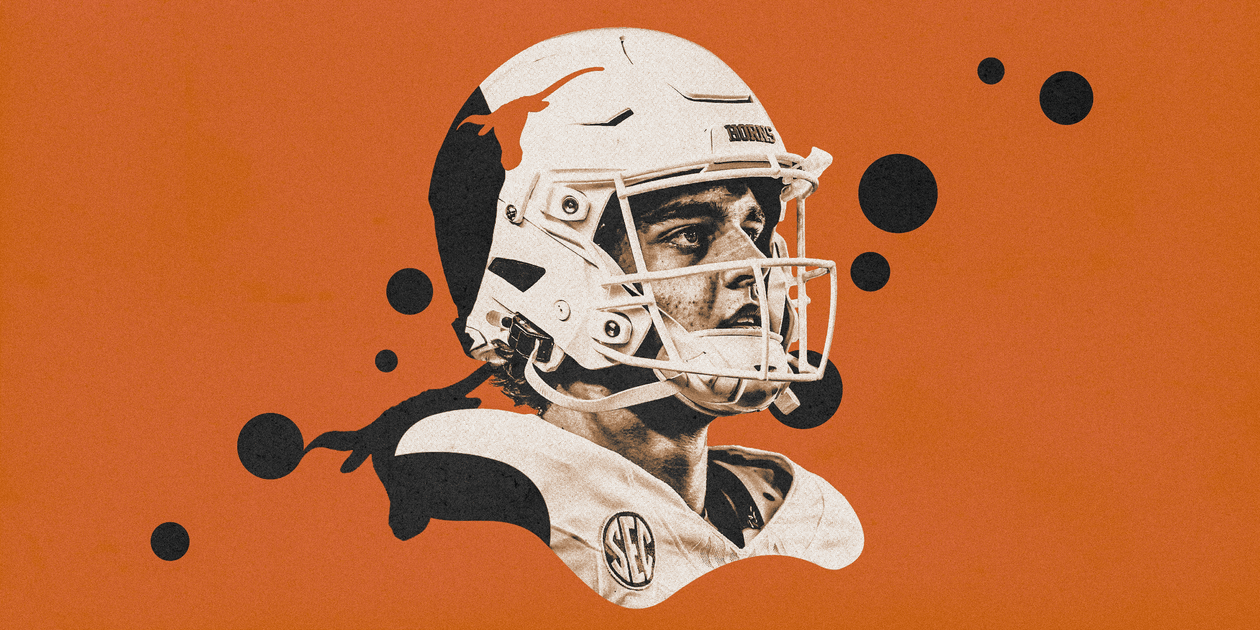

Many people are having a bad year in college football, but Arch Manning is having one of the worst. The Texas quarterback has gone from preseason Heisman Trophy favorite and projected No. 1 NFL Draft pick to a man synonymous with failure. It has reached the point that when his helmet came off late in Texas’ loss to Florida on Saturday and his backup Matthew Caldwell (who had a 13 to 8 TD/INT ratio for Troy last year) was forced to come in and throw a pass, it nearly sparked a quarterback controversy.

Manning has done so many ads that you probably don’t even remember the one he did for those Google cars that drive themselves. He remains the most high-profile player in college football despite being the public face of one of the most disappointing teams in the sport, a team that started the season ranked No. 1 in the polls (largely because of the hype for Manning) and now is outside the Top 25 entirely after losing to Florida.

Arch has claimed in the past to be hesitant to take so many paid advertisements — which might be the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard someone named “Manning” say — but if this keeps going, perhaps he can add one of those Progressive commercials in which backups like Tommy DeVito and Teddy Bridgewater show up to save normal people from banal but awkward situations.

Much of this is not entirely fair to Arch Manning, who, while certainly having his struggles so far, has shown occasional flashes of brilliance, is dealing with a wobbly offensive line and, we should probably try to remember, remains only 21 years old. (When I was 21 I was mostly hiding from gas stations where I’d bounced checks.) I don’t want to overdo it with a pity party here — his name is Arch Manning, I suspect his life is going to work out just fine — but I do wonder if it might behoove us to give a 21-year-old a little bit of grace and some room to grow. He does, after all, have two more seasons of college eligibility left after 2025 if he wants to use them.

But one thing is clear, and it’s something we’ve never really seen in college football but should probably start getting used to: Arch Manning, so far, is a flop.

We, as a society, love flops. There is nothing like a flop, because a flop flatters us. It justifies our suspicions that most of the world is just hype, that it’s full of hot gas, and that only we, the skeptical, cock-eyed, world-weary observers, are the ones wise enough to see through it. Flops remind us that the people in charge of our culture often know a lot less than they think they do.

There are flops in every aspect of American society. There are movie flops, infamous ones like “Ishtar,” “Heaven’s Gate” and “Battlefield Earth” to more recent vintages like “Dolittle,” “The Marvels” and glorious, glorious “Cats.” There are album flops (say, Katy Perry’s new album, though it sort of feels like a surprising percentage of people seem to be trying to will a Taylor Swift flop into existence), Broadway flops (“Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” most famously), TV show flops (“Cop Rock,” more recently “The Idol”) and even streaming platform flops (Quibi, Max). People even enjoy political flops; wherever you are on the ideological spectrum, the presidential campaigns of, say, Beto O’Rourke and Jeb (Jeb!) Bush are flops that remain well worth a chuckle.

But our most legendary flops come from sports. We love a sports flop. Specifically, we love a draft flop. Darko Miličić, Ryan Leaf, Mark Appel, Kwame Brown, JaMarcus Russell. These are names that will live on in sports lore forever. We remember names of players who flopped longer than we remember the names of players who panned out. (The two players drafted directly after JaMarcus Russell — Calvin Johnson and Joe Thomas — both reached the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but you will get a much stronger emotional reaction by saying the name “JaMarcus Russell” than either of theirs.) Draft flops hurt more because they originate in the emotion that fuels sports: Hope. Now we laugh at Darko and Leaf and Kwame, but only because we once believed them to be special.

We thought they contained greatness, which made us dream, but they did not actually contain greatness, which broke our hearts. There are no second-round draft flops, though I’m willing to grant the possibility that Shedeur Sanders could be a fifth-round one.

Arch Manning ranks 39th in the FBS in pass efficiency after Texas’ 3-2 start. (James Gilbert / Getty Images)

College football, for obvious reasons, has been devoid of flops throughout its history.

There have been highly recruited players who have disappointed: The most famous one might be Todd Marinovich, heralded in a notorious Sports Illustrated story in 1988 that called him the “first test-tube QB,” but Marinovich’s problems turned out to be because of issues with addiction (which he has recovered from and actually continues to help people through to this day) and, besides, Marinovich, before addiction felled him, was a good quarterback. (The UPI and Sporting News named Marinovich college football’s freshman of the year in 1989, and he was still drafted in the first round.) And certainly many coaches flop: I could name quite a few of them doing so this very second.

But we’ve never had a true-on college football draft flop before, because there was just never the possibility of one. There is no draft, first off, but more to the point, these players, until the last half-decade, couldn’t do advertisements or (legally) get paid, which meant you could hardly blame them for their own hype: There was a ceiling on just how much you really could get invested or disappointed in, or angry at, a teenager playing for a scholarship. No young college athlete could truly go global before having actually done anything.

Arch — again, so far — is the first college player to flop after being sold as the biggest star of his sport before most people had even seen him play. He’s not the first player to have the opportunity to: Just last year, in college basketball, Duke’s Cooper Flagg was the face of his sport, the obvious No. 1 pick, playing for the most well-known (and hated) college basketball brand. But Flagg did, in fact, turn out to be the best player, immediately. It was difficult to begrudge him all those New Balance ads when he was dominating on the court. This is not what has happened with Arch.

Arch is all over our televisions. He is the most well-known active college football player. Your casual fan uncle has no idea who Trinidad Chambliss, Fernando Mendoza or Dante Moore is, but he knows Arch. That he is playing so poorly — or at least that he is not dominating, and his team is losing — makes him a Classic Flop: a guy who can’t live up to the hype. And we love mocking guys who can’t live up to the hype.

This is the logical next step in the increasing professionalization of college sports: Treating the players — who, it cannot be repeated enough, only very recently were what we, in our actual lives, call “children” — as grown-up cautionary tales, people we click our tongues at, well well well, tsk tsk, I knew he wasn’t worth the hype, before they have even had the chance to grow up.

Arch Manning has started seven college football games in his life, and we already think he stinks. And — more importantly — we are already sick of him. And his glasses. Maybe especially his glasses. He is the first college football player this has happened to. He will not be the last.