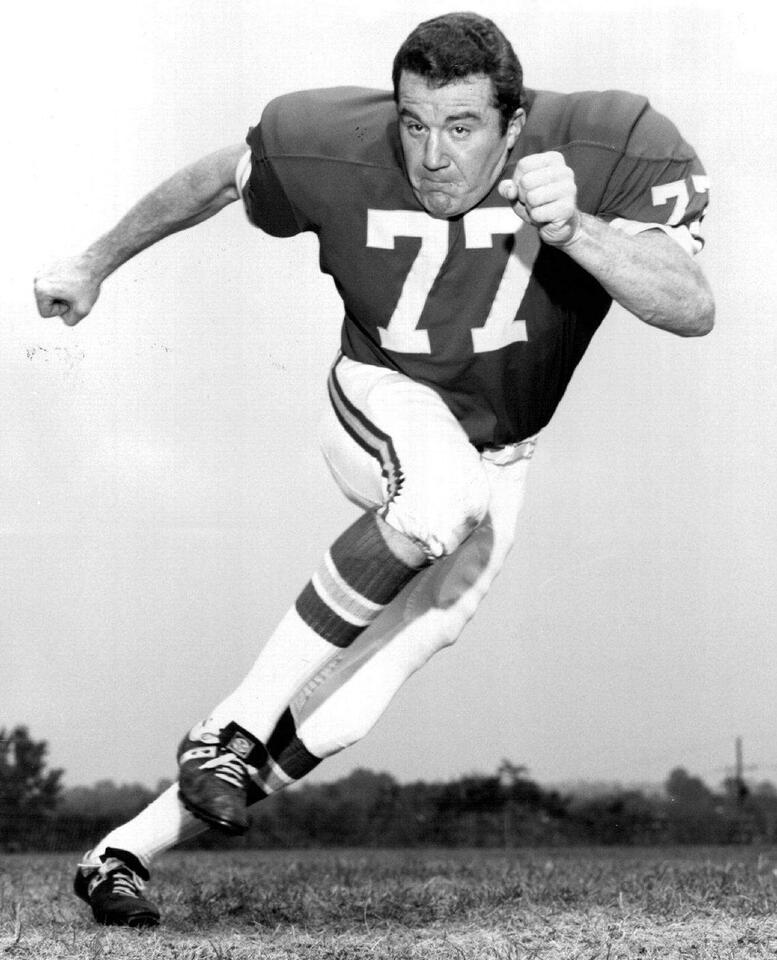

When it came to the 2025 Pro Football Hall of Fame class, Chiefs great Jim Tyrer had perhaps the most compelling on-field case among the top 60 senior nomineesand the 15 modern-era candidates.

No one else was a consensus six-time first-team All-Pro. Tyrer also was the left tackle on the AFL All-Time Team and a cornerstone of three franchise AFL titles and the Super Bowl IV champions.

So if the election were based purely on his playing exploits, as the PFHOF bylaws mandate, Tyrer would have been inducted long ago.

More immediately, he merited selection in the 2025 class as a finalist for the first time since 1980 because of his credentials … and an inescapable reason beyond those rules: A sub-committee felt liberated to nominate him because of the emergence of compelling evidence that severe brain trauma induced his horrific final acts in 1980 — murdering his wife, Martha, and then taking his own life.

Among the revelations of the exhaustive efforts of investigative journalist and filmmaker Kevin Patrick Allen, it came to light that a doctor treating Tyrer at the time is certain he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

The disease we now know to be all-too-real essentially was anonymous until the 2005 publication of Bennet Omalu’s study of the brain of the late Mike Webster.

But it certainly already existed. And it’s not going away: Of the 376 former NFL players whose brains have been donated to the Boston University CTE Center as of 2023, 345 were diagnosed with CTE.

Knowing what we know now, Doug Paone, the doctor who examined Tyrer two days before the murder-suicide, said in an interview with The Star in January that he was 100% sure Tyrer had CTE. And Concussion Legacy Institute founder Chris Nowinski told me he had 95% certainty Tyrer had the insidious condition caused by repetitive head trauma and known to cause aggression, mood swings, depression and paranoia.

Amply more persuasive testimony was gleaned by Allen, who has spent much of the last six years consumed with working and reworking a documentary about Tyrer called “Beneath The Shadow” — a venture he entered not with an agenda but an open mind to tell a complicated story.

Alas, none of that resonated with enough PFHOF voters, some of whom publicly flouted the bylaw that off-field “situations … are not to be considered.” Only Sterling Sharpe was elected among the three senior finalists in a pool that also featured a contributor and coach finalist. Up to three of those five could have been enshrined.

As a PHFOF voter (who advocated for Tyrer), I’m bound to confidentiality about the deliberations. But I do object to the rule that prohibits discussion about anything off the field: By any logic, it would leave such a conspicuous matter to fester if unexamined.

Now, though, voters have a fresh chance to do unwrap a flawed narrative and bring the broader issue out of the shadows.

This week, the NFL’s senior committee voted to reduce a preliminary list of 52 nominees down to 25.

The names of those advancing are expected to be announced some time next week. Tyrer should be on that list, along with former Chiefs greats Otis Taylor and Albert Lewis — each of whom also have tremendous cases of their own.

If Tyrer isn’t put forward again this time around, we’ll regenerate this next year.

If he is, though, I hope the committee tasked with whittling down the senior list, and ultimately the entire 49-person selection committee and Hall of Fame itself, will seek to further open its minds and hearts to reconcile the inconvenient truth: that what happened on the field is entwined with what happened off it.

As Paone told me in January, “I’m sure that if he never had played offensive line, or had never been a football player, for that matter, he would never have killed his wife and himself.”

And I hope the committee(s) will recognize what Tyrer’s four children resolved long ago: that Jim Tyrer’s tortured final months and last acts were not of his own making, but those of a monster that had seized him.

(The family, to be clear, will not campaign for Tyrer to get in the Hall of Fame. But as Brad Tyrer told me earlier this year, “We just feel like if he gets in, and his story is retold and people revisit Jim Tyrer as a man, that the true legacy of him will be out there. Not what it is today.”)

And I wish all concerned would realize that it perpetuates an inherent blind spot to employ a bylaw that squelches discussion and thus ensures a process with no provision for expert guidance on an infinitely controversial and complex topic.

In speaking with some voters afterward, Allen was struck by several who had misperceptions of aspects of CTE. When Allen corrected the assumption of one, he recalled, the response was, “Well, I’m not an expert in that.”

“Exactly,” Allen said.

By way of another example, Allen said he heard voters say “I can give him a pass here” up to a certain point of behavior reflecting brain damage.

Until murder.

“That logic doesn’t follow if your brain didn’t work on all those other grounds,” he said. “The only thing that changes is your ability to accept it.”

Indeed, to accept it surely would open the Hall of Fame up to a different sort of criticism. It would also seem a tacit admission that the game itself was part of it — which no doubt would be a blow to “The Shield” signifying both the NFL’s logo and metaphorical sense of itself.

Meanwhile, Allen can’t accept the implications of it being left this way.

So he undertook an elaborate methodology to examine the number of head-involved hits Tyrer would have sustained through 22 years of practices and games of football, including four at Ohio State and 14 in the AFL and NFL. By what he termed a conservative estimate, he determined that Tyrer had been engaged in 83,000 to 88,000 such hits.

“And we know now,” Allen said, “that it’s not concussions but the number of hits that matter.”

By the same formula, he estimated Mike Webster would have sustained 91,000 hits … but with better equipment.

That speaks to another dimension of this: why CTE and brain trauma overall would likely befall Tyrer, whom Allen calls “a study of one.”

By his reckoning, Tyrer was vulnerable to risk in multiple ways.

Because of his unusually large head, Tyrer required custom-made helmets that seldom fit right and lacked the suspension and padding of even that antiquated generation of plastic helmets.

Multiply that by an era in which players were encouraged to use those helmets as weapons and offensive linemen weren’t allowed as liberal use of their arms as they are today.

Factor in Ohio State’s “three yards and a cloud of dust” style under Woody Hayes and Chiefs coach Hank Stram’s increasing emphasis on the run later in his career. In Tyrer’s last six seasons in Kansas City, the Chiefs rushed 2,981 times and passed on 1,945 plays.

“The worst position, worst era, worst helmet …” he said.

At a time when coaches pushed players to “do it again” even when they were hurt and get back in there when they had their “bell rung.”

It was the sort of bell, alas, virtually always answered by Tyrer and others, like his teammate Ed Lothamer, who died in 2022 and was diagnosed with CTE after his family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

As Allen considered further ways to quantify Tyrer’s plight, he sought an independent assessment. Not solely on the issue of brain trauma, he explained, but concerning who, or what, was in control when he did what he did. So he turned to a source he termed an expert in medicine, law and the science of free will: David M. Reiss, a California psychologist who has worked with hundreds of traumatic brain injury cases.

In hopes of securing the sort of forensic analysis that would be worthy of a court of law, Allen turned over everything he’d discovered over the last six years: audio and video interviews with family, friends and experts, documents, writings of Tyrer’s that demonstrated his decline. And then some.

While careful to note caveats based on the lack of medical and psycho-sociological data available 45 years later, Reiss concluded this in a report he entitled a Retrospective Psychiatric Review of Available Information:

“Within reasonable medical certainty Mr. Tyrer suffered from (what would now be diagnosed as) post-concussive/CTE pathology and symptomatology, including cognitive impairment and complex psychopathology (depression, loss of self-esteem, disruption of thought processes, probable paranoia, loss of impulse control, etc.).

“Within reasonable medical certainty the above pathology rendered Mr. Tyrer a man with seriously diminished legal capacity vis-à-vis judgement and impulse control.

“Based upon the data available to me, but for Mr. Tyrer’s diminished capacity due to post concussive/CTE pathology, within reasonable medical probability, Mr. Tyrer would not have committed violent acts, and in my opinion, almost certainly, Mr. Tyrer would not have murdered his wife and committed suicide.”

For all this, that’s ultimately not the same as 100% certainty. CTE still can’t be diagnosed without a direct study of the brain. CTE also isn’t an excuse — a term that Allen hears and finds triggering.

“Nobody said it was an excuse; it wasn’t something that he wanted,” he said. “But I finally worked it through in my head when I hear that, or when somebody says, ‘It’s still a guess’ — It’s more a wish on your part that it’s not true than it is a guess on mine. …

“A wish for you that it’s not true, so you don’t have to deal with it.”

One way for the committees not to have to deal with it, of course, would be to adhere to the rules and vote based simply on Tyrer’s impeccable on-field qualifications.

But the better way, the best way, would be for the Hall of Fame to welcome discussion and expertise instead of holding fast to a guideline that lets it hover unacknowledged but ever-present.