If you type “WSL” into Google, the first search option that often comes up is the Women’s Surf League — the global home of surfing.

This is, apparently, a huge problem. For Women’s Super League fans, for me as a Women’s Super League journalist and for the entire Women’s Super League franchise, and, let’s go there, English women’s football as a whole with its glaring SEO inferiority to global wave riders.

Which is what brought us to Monday, the day the WSL put its flag on the SEO moon and gave us the rebrand none of us asked for.

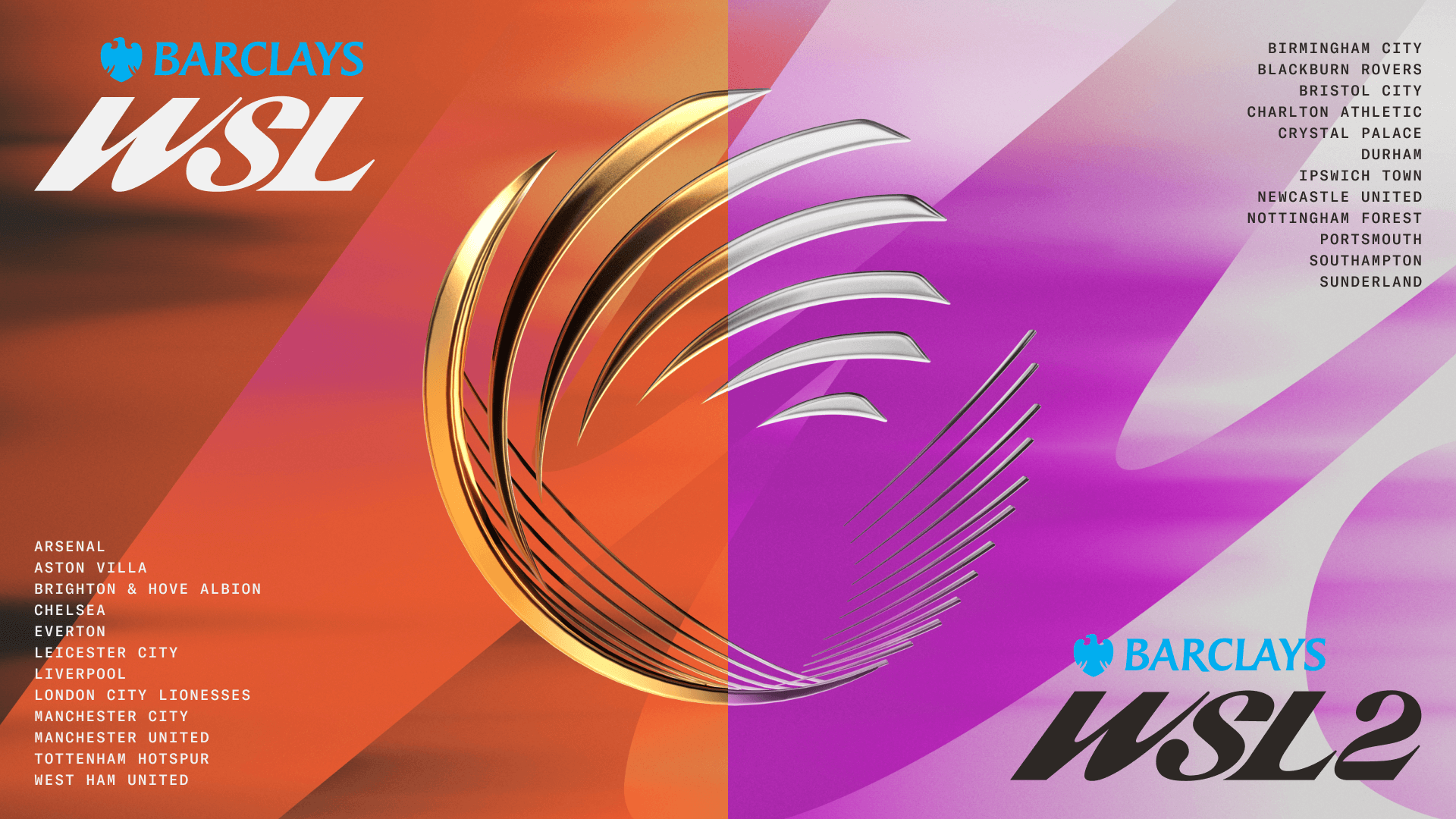

The WSL — the top level of women’s football in England — revealed a multifarious rebrand for the 2025-26 season, featuring a change of name for the Women’s Championship (WSL2) and a change in name for the Women’s Professional Leagues Limited (WSL Football, previously Newco, the independent body that has overseen the top two leagues since the start of the 2024-25 campaign).

Plus, there is a “new visual identity” and website.

WSL Football attempts to explain that vision with a hipster’s gilded Winged Nike remake (gold edition) and the word “WSL” written in hyper italics against an orange or purple background.

It looks like a poor recasting of a 1960s Oscars emblem, or a new-age airline that flies exclusively business class and has shrimp cocktail as a welcome snack. The font is trying to say “forward progression,” but instead gives someone-falling-fast-down-a-mountainside-due-to-unsuitable-shoes vibes. What the design will be like to print on shirts, hats, towels and friendship-bracelet beads is another conversation altogether.

But this isn’t about changing a perfectly adequate logo. It’s about what message this change is projecting.

Because within the swirling skeletal arches of WSL Football’s new Hunger Games-esque logo lies a kind of anti-faith in English women’s football itself. Rather than addressing the fundamental issues at play in the top two tiers, the spangle and tinsel come first. Football as tableau first, sport second.

For an organisation tasked with moving the game forward into a new era, the order of operations feels out of date. One of the reasons women’s football has struggled to be taken seriously by its male counterparts is the perception that the garnishing is more important than the substance.

Choosing between colour swatches or serif or sans-serif fonts or the angle at which an italicised letter starts speaking to something primal in us is much harder than considering things like (but not limited to):

Confronting these problems may not sell well to prospective investors, but some colour around the edges and pixie dust thrown at the issues until they dazzle in the golden hour won’t solve the issues underneath either. And between the blinding sparkle and the slick AI-generated social media posts, how can anyone possibly ask what the future looks like? Or how we’re addressing audience malaise or stuttering attendances while avoiding turning this whole thing into a Taylor-Swift-shaped-Glastonbury? Or whether the foundations are strong and imperious enough to uphold the £1billion ($1.3bn) industry promise fans are being pitched?

Instead, women’s football has been hitched to the Festival Girl Power Summer brandwagon. Want to show off your support of the WSL? Try out the new sassy Macbook-appropriate stickers, featuring totally hip and cool jargon like “pitch please” or “I kick a ball for a living” (the latter conveniently forgetting that for many of the players in the Championship — sorry, WSL2 — the phrase “a living” is doing a lot of heavy lifting).

You can even get your hands on some “Access All Areas” wristbands in order to feel like attending Arsenal at Everton at 2pm on a rainy afternoon in February is just like gliding backstage at an Olivia Rodrigo Coachella set.

None of this is to say football cannot be fun or exciting. But why is the default assumption that women’s football fans cannot enjoy a 90-minute game for the 90 minutes of football alone? Why is the instinct to presume fans need to be enticed in through flashy lights and promises of perpetual dopamine hits?

And beyond the issue of faith in the very sport this organisation is purported to be placing faith in, there’s a side to the “all access” tag that starts to feel less gimmicky and more sinister when considered through a wider prism. At what point do we start exploiting that tag in its most literal sense? A point where players really are commodified, told to flay themselves piece by piece to baying audiences, their dressing rooms and internal sanctums now streaming opportunities? Because this is how you grow a sport, right? Give the people what they want?

Only, what if this isn’t what people want? What if that isn’t giving people the credit they deserve? What if the people don’t actually want football-adjacent? What if they just want football?

(Top photos: WSL Football)