You might walk past the International Dispute Resolution Centre (IDRC) in central London a hundred times without noticing it.

Dwarfed by nearby St Paul’s Cathedral, the smart office building where arbitration rooms can be hired by the day for up to £5,000 ($6,580) seems unassuming.

But the IDRC has emerged as a key battleground for some of English football’s most compelling contests over the last 12 months. It is where Manchester City faced the Premier League’s 115 charges at the back end of last year — the result is still to be confirmed — and where Burnley have sought compensation of up to £60million from Everton in what could yet be a landmark case.

Lucas Paqueta, too, had his playing career saved in these nondescript rooms once his FA charges for spot fixing were fought and dismissed in September.

All three highly confidential cases had tens of millions of pounds, as well as reputations, riding on the outcome and each helps to illustrate the sea change in football’s relationship with law.

An industry once reluctant to pursue courtroom conflict can increasingly be found embracing it. Huge sums are being invested in defending positions and challenging governance. The brightest legal minds are hired to do the bidding of stakeholders, all with the intent of shoring up positions and strengthening claims. Costs, to some, are almost inconsequential when so much is on the line.

Manchester City’s protracted 115 charges case remains the biggest, but football currently finds itself mired in legal battles like never before. The last seven days have brought threats to the Premier League from the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) and three top agencies (CAA Base, CAA Stellar and Wasserman) ahead of a vote on financial reform on Friday.

The International Dispute Resolution Centre in London (Lucy North/PA Images via Getty Images)

The current financial regulations, known as Profitability and Sustainability Rules (PSR), have dragged Everton (twice), Nottingham Forest and Leicester City into legal battles and appeals since 2023, with the latter still on the hook for a potential points deduction. The Premier League, at the last count, was having to spend north of £40m a year on legal fees.

Widen the focus and there is more. FIFA had found its authority being questioned by player unions in two separate cases centred on the demands of the international match calendar, soon after ending a different battle with New York-based event promoter Relevent Sports, who had pushed for the right to take domestic games to new territories.

UEFA has faced its own scraps, too. A22 Sports Management, the company behind a proposed European Super League, has initiated a string of legal proceedings, refusing to give up on a plan that would bring down the house. Football is no stranger to infighting in its world of self-interest and the rising revenues have unintended consequences. More money, more (legal) problems.

“Clubs have been bought by active and aggressive investors,” says Jamie Singer, a founding partner of Onside Law, a firm specialising in sports law since its launch in 2005.

“These are not the old local chairman that return to support their club after making some money. These are corporate or state-backed investors who see football as a growth opportunity as much as a passion and are used to shaking up their investments and getting their own way. They are prepared to challenge the current system and rules, and each other.”

Welcome to football’s new age of lawfare.

This is a big week for the Premier League. Its 20 clubs will be asked to vote on the introduction of new financial rules on Friday, including a controversial “top to bottom anchoring” (TBA) proposal that would effectively bring in a hard cap on what can be spent on player costs.

There are no guarantees it will pass given the opposition from within the room but those looking in have already signalled their intent to bring challenges. PFA chief executive Maheta Molango, a former footballer but also a qualified lawyer, was among them and recently warned in UK newspaper The Times that these new rules would “guarantee more of the same” costly legal battles. “The legal ground is shifting,” Molango warned.

PFA CEO Maheta Molango is unhappy at salary cap proposals (Steven Paston/PA Images via Getty Images)

And how. The Athletic has spoken to a range of legal experts and stakeholders, including some on the grounds of anonymity to protect their working relationships, to examine the fundamental changes to football’s relationship with law in the last decade. It is now as much a weapon as a shield, with the game’s exponential growth forcing greater legal expenditure than ever before.

It was not always this way. Exceptional cases made their way to a courtroom, but there was an element of deference to the decisions of governing bodies and football associations.

Swindon Town, for example, were relegated two divisions in 1990 when accepting 36 charges related to making illegal payments. After initially launching a High Court appeal, they instead opted for their case to be put before the FA’s Appeal Panel. These were not considered complex matters, even with Swindon being denied a place in the English top-flight. An appeal was heard within four weeks, reducing Swindon’s punishment to a single relegation.

The Premier League, in particular, is a world that sees the stakes climbing year on year.

“Money and the push for competitiveness within the professional league system all tie into the fact people are willing to, and want to, dispute things that arise in the sport,” explains Alistair Maclean, Partner at Level and former Group Legal Director of the Football Association.

“That could be anything from a footballer’s playing contract through to disputing what’s happened on the field of play, in order to maintain or gain a competitive advantage, avoid relegation or achieve promotion.

“These clubs are big businesses and the people that own them view them perhaps differently to how they’d view clubs 25 years ago. Everything has naturally become more professional, including the governance structures that go around that. It’s like any other industry. There has to be an appropriate level of regulation to ensure that there’s protection.”

Premier League clubs generated £6.3billion in 2023-24 and have come to act accordingly. Every club now has in-house counsel, teams of lawyers that can run into double figures, tasked with overseeing commercial deals, safeguarding, tax and finance. The industry’s growth demands it.

External legal support is also commonplace. Big city firms are now regularly engaged with Premier League clubs, who seek the same advantages off the pitch as they do on it.

“These investors are billion-dollar funds or billion-dollar owners who are quite happy to have a legal tussle because they can afford it,” says John Mehrzad KC, of Fountain Court Chambers. “Spending tens of thousands of pounds, or even hundreds of thousands of pounds, on a challenge like that is meaningless for them.

“Whereas once upon a time there would have been a lot more deference to sport and its regulation, that is gone because people can afford to challenge these things. It’s no longer disciplinary matters which the criminal bar would have done a lot of. You’re now coming to heavy-duty commercial barristers, competition law barristers, to take these points. It makes sense in terms of financial aims, and also their capability to afford it.”

It is impossible to tell the story of an altering landscape without mentioning the influence of Manchester City.

Simon Cliff, once a high-flying corporate lawyer, has been the club’s general counsel since 2009 and has been a consistent presence in running battles against the Premier League. Those 115 charges, heard across 12 weeks at the back end of last year, will have the biggest consequences, but it was a legal challenge to the Premier League’s Associated Party Transaction (APT) rules that illustrated City’s willingness to take a very modern approach in conjunction with leading law firms, such as Freshfields and Clifford Chance.

Simon Cliff (wearing glasses) with other Manchester City executives earlier this year (Nick Potts/PA Images via Getty Images)

City’s wish has been to grow their already enviable commercial income and reduce any obstacles placed in their way by what they famously called the “tyranny of the majority” in their legal submission ahead of the case against the Premier League’s APT rules last year. Only in September did City accept that those APT rules were “valid and binding” after a bruising back and forth.

The approach of City, who also successfully overturned a two-year ban from European competitions for “serious breaches” of UEFA’s financial fair play rules at the Court of Arbitration for Sport in 2020, has been underpinned by the wealth of owners, the Abu Dhabi United Group, for whom legal costs are of little concern.

Yet other clubs, not bankrolled to such a vast extent, are now adopting similar tactics. Everton, Nottingham Forest and Leicester have turned to big firms and high-profile names. Paqueta did too when he employed Nick De Marco — whose profile on his Blackstone Chambers says has represented more than 45 clubs and players ranging from Cristiano Ronaldo to Joey Barton — to fight his corner over spot-fixing charges from the FA.

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), owners of Newcastle United, has also shown an aggressive legal streak across other sports. There has been all-out war between the PIF-backed LIV Golf and the Professional Golfers’ Association of America, proving football is not alone in seeing disruptors make their mark through litigation.

“There are clubs that have adopted the model from the U.S., where legal fees and lawyers become centre stage and part of your corporate tactics,” says Singer.

“They make it clear money is no object and drown the other side by challenging everything and ‘over lawyering’. The other side are forced to incur far more costs than anticipated to defend themselves and regardless of the merits of their arguments, the scale of the costs make the risk of litigation far greater.”

LIV Golf has been embroiled in legal battles with the PGA (Raj Mehta/Getty Images)

The Premier League, too, does not scrimp on its legal representation. Adam Lewis KC, also of Blackstone Chambers, is considered to be among the most respected sports law figures in the UK, as are the supporting barristers from city firm Slaughter and May tasked with taking errant clubs to task. But hiring such representation comes at a cost, hence those eye-watering £40m annual legal fees. Those are funded by money from a central pot, which could reduce the sums distributed to the 20 clubs at the end of each season.

“I understand why there’s a lot of litigation, but it doesn’t mean that the Premier League are not doing their job,” says one anonymous senior silk, who has been involved in legal cases against the Premier League.

“It’s because the stakes are very high and if you find there’s a potential breach then the club is always going to fight like hell to try and prove there isn’t. You don’t just have to accept it. No one is going to roll over because the stakes are so high. That’s not a failure in supervision or control from the Premier League. The number of legal claims we’re seeing is almost inevitable because the stakes have kept rising.”

City have always denied any wrongdoing in their 115 charges case, but the anonymous senior silk added that they believe that if the club are found to be liable, they could face a “tsunami” of claims from other clubs.

“Society, generally, has reached a point where everyone is much more aware of their rights if they’ve been wronged,” adds the senior silk. “People wouldn’t even have thought about these things 40 or 50 years ago, and who they could sue. They’d just suck it up. Has that come from the U.S.? Possibly. But as soon as there’s money involved, everyone is incentivised to think about the repercussions.”

Burnley’s case against Everton, with a decision expected before the turn of the year, promises to offer timely guidance on what a wronged party can expect.

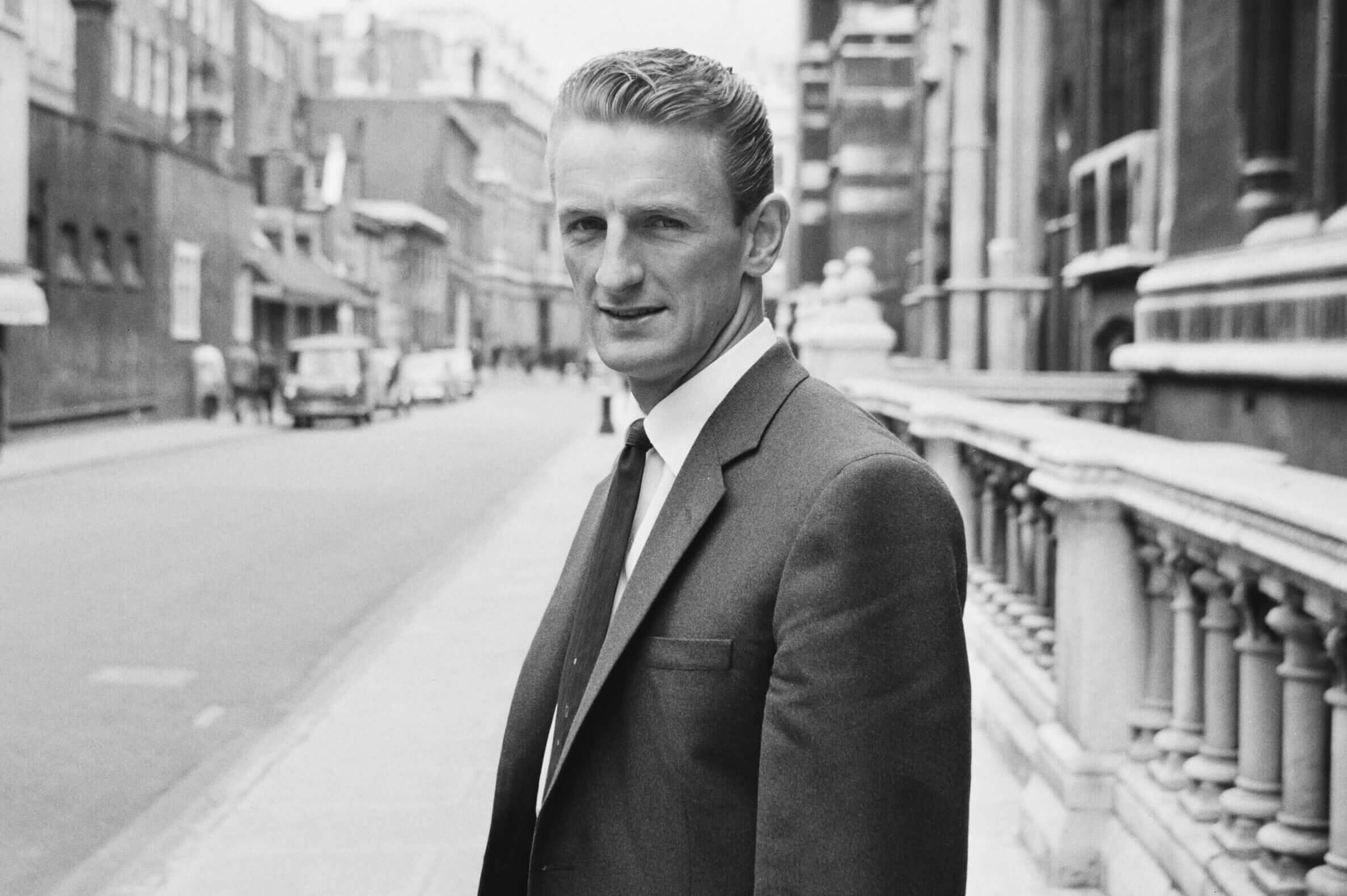

Much of this, perhaps, can be traced back to George Eastham, a man who died last year at the age of 88. Shortly after Jimmy Hill had led the PFA’s successful bid to abolish a £20-per-week maximum wage in 1961, Eastham was also attacking the old order.

Newcastle United had initially refused to sell Eastham to Arsenal, relying on their employer powers to block a move. The transfer eventually progressed but Eastham, later a member of England’s 1966 World Cup squad, took his former club to the High Court in 1964 to argue it had represented a restraint of trade. Eastham won, transforming an outdated transfer system and allowing footballers greater freedom of movement.

George Eastham led a landmark case against his club, Newcastle United, in 1964 (Harold Clements/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Eastham’s motivation was to enjoy greater rights as a player, unshackled by established rules and governance. In the mid-1990s, the Belgian footballer Jean-Marc Bosman also broke down walls to allow any player to move as a free agent once an existing contract had expired.

“That was the beginning of seeing football as being a financial product at that stage, because the Premier League had only been launched three years before, there was more money trickling into wages,” explains Mehrzad.

“Becoming a free agent and being able to move was very significant because that money would then turn into wages rather than transfer fees. Bosman created a tidal wave of issues with clubs saying, ‘(players) are our assets, if we don’t get paid, we’ll go bust, and what’s the point in training them if they’re just going to run down their contracts and then leave?’

“There needed to be this resolution, there needed to be a framework that safeguards clubs. It couldn’t just be that players could walk out and clubs could be left destitute. Everyone knew that there were these European issues around freedom of movement, competition law, discrimination, and essentially, there is a bit of a fudge in 2001. FIFA and UEFA were happy because they retained being the global and confederation leaders.

“Nobody really wanted to rock the boat over the next 10, 15 years, because this was a sort of way of just preventing further chaos.”

Football, though, has kept churning out legal cases all the while.

“If you searched the CAS website, you can see that between 1986 and 2024 there were 2,580 reported cases,” says Maclean, once of the English FA. “Of those, football is 1,496, so that’s 58 per cent. The next highest sport is all the way down to 198, which is athletics.

“There’s a vast difference, 7.8 per cent against 58 per cent, in the types of disputes that are running through the highest sports arbitration body in the world. That’s been established for 40-odd years, so there’s some good statistical basis behind it. The very basic reason for that difference is the global elite participation numbers for football and the large sums of money involved. It is that simple.”

Yet football’s modern world feels different. Governing bodies are being challenged readily, facing litigation designed to disrupt. FIFA, UEFA and the Premier League, organisers of football’s three biggest competitions, face regular challenges to their authority from disparate parties who want to alter the direction of travel.

“We’ve seen the arrival of a lot of people who openly challenge the system because they come from an environment where those battles exist and are common,” says one leading stakeholder in the English game. “With football, no one really had the courage to do it before.

“Even within the leagues, we’ve now got people willing to challenge the authority of the league. People have come from the outside and said, ‘Hold on a second, who are these guys to tell me what kind of deal I can and can’t sign with a third party?’”

Manchester City fans show their support for Lord David Pannick KC, who led their case against the Premier League (James Gill – Danehouse/Getty Images)

There is little denying that the influence of the legal industry has grown and is growing within sport. The rising costs, to most, are considered a byproduct of football’s development, but there is no consensus as to where this all leads.

There are some observers who consider the current rush of legal cases a bump in the road. The advice of others, though, is to strap in and prepare for more in the years to come.

It would be a stretch to suggest that football’s future will be decided by lawyers, but the last decade has shown a power that is now becoming clear to supporters. Take De Marco, revered by the fans of clubs he has helped out of sticky spots, and Lord Pannick, subject of a banner at the Etihad Stadium in 2023 when hired to lead Manchester City’s case against the Premier League.

Players and coaches will always be the chief drivers of results in football, but legal practitioners are not far behind.

Additional reporting: Jacob Whitehead