What’s there to lose?

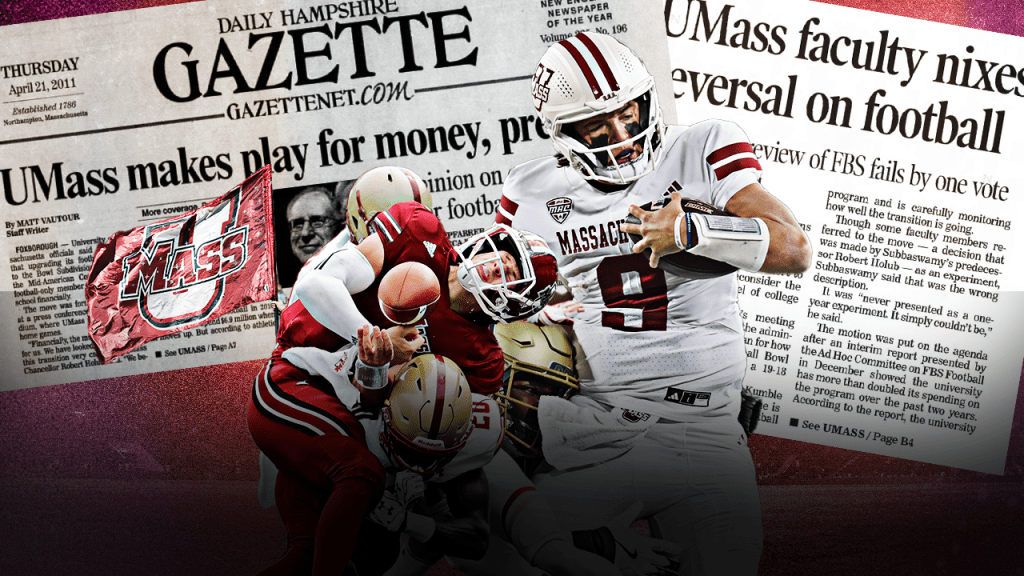

That was Nelson Lacey’s thinking in 2011, when the University of Massachusetts Amherst—a consistent force in the second tier of NCAA Division I—decided to make the leap to the premier Football Bowl Subdivision. A professor of finance, Lacey twice co-chaired the school’s faculty athletic council and also helped lead an ad hoc committee on FBS football, where he consistently championed UMass’ athletic aspirations.

In a recent telephone interview, Lacey, now professor emeritus, said he always recognized the FBS “experiment” as a longshot for success. But for what was projected to be a few-million-dollar annual increase in the football team’s budget, he believed it a no-brainer. What else, he asked, could the university invest in that offered—however remotely—the chance at catching lightning in a bottle, boosting enrollment and donations and the national reputation of the commonwealth’s 162-year-old flagship campus?

Now, Lacey is ready to admit defeat and thinks the school might be wise to do the same.

“Maybe the Premier League has it right—that the bottom 10% get wiped out automatically,” Lacey mused, referring to the relegation process in English soccer.

On Tuesday night, the Massachusetts Minutemen will try to salvage a speck of pride from a season that has cemented their status as the most woeful FBS program. Sitting at 0-11 following last week’s 42-14 loss at Ohio, the team has one last chance, at home against Bowling Green, to avoid a winless campaign—something they’ve managed every year, but for the COVID-shortened 2020 slate, during their ignominious streak of 14 straight sub-.500 seasons. This year’s squad currently ranks 238th across all of NCAA, according to the SP+ ratings metric by ESPN’s Bill Connelly, 53 spots below the next closest FBS school. There are 85 FCS teams and 15 DII programs with that rank higher.

“If we go without a win this year, with all that, I can maybe see some real movement [to leave FBS],” Lacey said. Though no longer plugged into the discussions on campus, he added, “I can just imagine folks thinking: This is it, we are at the end of the road.”

Since 2012, UMass has posted the worst record in FBS, winning only 16% of its games; the next worst record belongs to Kansas, which has won 26% while competing in the Power Five. Not only are the Minutemen reliably falling to fellow FBS opponents, they’ve also lost four of their last eight games against FCS schools. Accompanying these brutal game logs has been a parade of other indignities.

In one such turn that felt downright prophetic, a rented video board in McGuirk Alumni Stadium collapsed during the 2014 UMass home opener, which also happened to be the first time the team had played in its on-campus venue in three years. The crash sent hydraulic fluid spilling onto the turf, prompting a hazmat team to be summoned, but it could only do so much damage control: UMass went on to lose 47-42 to Bowling Green. Earlier this season, the team drew online ridicule when it launched fireworks following a field goal that cut its deficit against Northern Illinois to 42 points.

With its dubious legacy, UMass has come to serve as a case study for the irrational exuberance that drives so many college programs to chase top-tier athletic status despite the structural, financial and competitive realities stacked against them. Although advertised as a move to forge its financial autonomy, the FBS bottom feeder instead has become one of the most heavily subsidized athletic departments in America.

The Minutemen’s 14-year football misadventure shows how difficult it is to douse a financial dumpster fire once it’s lit. After all, who wants to be the athletic director, or chancellor, or board of trustees president to call it quits on a dream, even if it wasn’t your dream to begin with?

And so UMass is doing what many hard-luck gamblers have done before: double down. The school has rejoined the MAC conference, is investing millions into stadium renovations, and is committed to paying both coaches and players among the highest totals of any university in its new league.

For athletic director Ryan Bamford, this “hard reset” is something that should have happened earlier. In a recent phone call, he said the UMass football team’s FBS struggles have been due to a dearth of resources, including the funds allocated from main campus.

“For a program to have $2 million or less from [the school’s] general operating funds, that’s not a lot,” Bamford said. “When you consider that the university budget is about $1.8 billion—billion with a ‘b’—and we’re getting less than $2 million to go to football, I think that tells the story of why we are where we are. You get what you pay for.”

The university’s current chancellor Javier Reyes, in a statement, wrote off the last 14 years as little more than FBS prehistory.

“This is year one of our reset for football,” said Reyes, an economist who previously served as interim chancellor at the University of Illinois Chicago. “Starting this season, we have the conference, the personnel, and a plan to invest for success. …This isn’t just an investment in football; this is an investment in the spirit of UMass.”

To be sure, first-year undergraduate applications have risen steadily during the school’s time in FBS, increasing 32.3% over the last decade—a time where many colleges, especially in the Northeast, are seeing declining enrollment because of demographic trends. Yet it’s hard to know how much credit goes to football; applications increased by 108.9% over the decade preceding its FBS transition.

Asked whether the football team’s top-tier status was directly responsible for enrollment numbers, as well as the school climbing 35 places to No. 64 on U.S. News and World Report’s university rankings in the past 15 years, Bamford chose instead to discuss the program’s hypothetical future impact.

“We’re cognizant of what a successful football program can do to enhance all of those data points,” he said. “The power of football is real, and we are absolutely resolved to get this right.”

Lacey readily concedes, in hindsight, that the plan to move to FBS should have included a firm deadline to reassess if things went poorly, as some faculty had suggested.

“The faculty wanted to believe they had some chips in the game here, but I don’t really think they did,” said Lacey. “I firmly believe that some people on the UMass board of trustees wanted to make this move, and there was nobody who was going to stop it.”

James Karam, a real estate developer who chaired the school’s board of trustees at the time, was publicly credited for being the driving force behind the transition. He did not respond to an interview request but his nephew Stephen Karam, the school’s current board chair, offered a tacit defense of the decision.

“By any measure—academic achievement, graduation rates, research portfolio, reputation, and rankings—UMass Amherst has risen to the top tier of public research universities,” Stephen Karam said in a statement, provided by a university spokesperson. “We take pride in UMass Amherst’s commitment to excellence in every facet of its offerings, and we wholeheartedly support the campus’ strategic vision for advancing its football program.”

UMass formally announced its plans to transition to FBS and join the MAC at an April 22, 2011, press conference in the media room of Gillette Stadium, which was set to become the temporary future home to Minuteman football. New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft had offered UMass use of the NFL stadium while it made improvements to Warren McGuirk Alumni Stadium.

In a euphoric 90-minute presentation still available on the UMass athletic department YouTube page— there to either serve as a cautionary tale or totem of morbid curiosity—chancellor Robert C. Holub declared that the move “advances our aspiration to assume our rightful place in the upper echelon of national public research universities.”

Holub insisted that the school had conducted a “sober” financial analysis and concluded that, from a budgetary standpoint, “the move will work well for us.” He even predicted that, within a few years UMass would draw less and less from its general fund to support the athletic department, even with the increase in spending.

About that: In the fiscal year 2010, athletics received $20.2 million in campus support and student fees. By fiscal 2024—the most recent year with data available—those subsidies had grown to $49.5 million, the fifth-highest among public FBS schools, according to Sportico’s college sports finances database. That amounted to 80% of UMass’ overall athletics budget, the highest share in the nation. Moreover, the program’s reliance on such funding is virtually unchanged from its pre-FBS days; from 2009 to 2011, subsidies covered 81% of athletics spending.

Those funds are not all directed towards football, and part of that increase reflects a jump in cost of living and scholarship costs, plus facility debt service covered by the school. Of the department’s roughly $11 million in student fees, Bamford said, about $2.7 million go to football. Of the nearly $28 million in direct institutional support, the team received just under $2 million.

Amid the new push, Bamford estimated aid would grow by “at least” $1 million to $3 million in the coming years. In effect, the school is now actively choosing to do the exact thing that James Karam and Holub said moving to FBS would avoid: increasing the football team’s reliance on the university’s general operating funds.

There’s also been a bit of an about-face on where the Minutemen would play as an FBS program. During that 2011 announcement, then-athletic director John McCutcheon said Gillette Stadium would be the team’s primary home for the “foreseeable future.” As proof of concept that an NFL venue 85 miles from campus was a viable option, the chancellor and others touted a 2010 game that UMass played at Gillette against DI-AA rival New Hampshire that drew 32,848 fans.

Starting in 2012, the team played 21 games at the stadium as an FBS program and never eclipsed that number. UMass averaged 14,143 fans for those games and only once surpassed 26,000. Amid dwindling crowds, the team moved back to campus nearly full-time after the 2016 season. At McGuirk, the team has averaged 9,338 so far this year, among the lowest totals in FBS, and well below the 15,000 minimum once in place for programs in ’s top tier.

The first coach tapped to lead UMass football to its “rightful place” was Charley Molnar, who had most recently served as offensive coordinator at Notre Dame under Brian Kelly. Hired in December 2011, Molnar took the helm brimming with confidence. He lasted exactly two years before being pushed out.

“I was going by their past success, that the school knew what it took to win, knew when it was time to step up, that they put valuable resources where they needed to be,” Molnar said in a phone interview, offering his first public remarks on UMass since his firing in December 2013.

As Molnar notes, the original intention of the school was to join the Big East—something Bob Kraft himself had lobbied for—following in the footsteps of nearby UConn, and that plan remained in place.

“As a first-time head coach—I am so full of optimism and enthusiasm—that was the dream, to build up my team with two years in the MAC and move on,” Molnar said. “We did not want to stay in the MAC long-term; it was a placeholder until we were able to get into the Big East.”

But almost from the moment he arrived, a harrowing challenge emerged. Holub, the chancellor who hired him, retired in June 2012, just before the Minutemen commenced their first FBS season. Faculty opposition quickly coalesced, spurring a wave of negative headlines in both local and national media. Despite its lofty ambitions, UMass at that moment still bore all the hallmarks of its recent Division I-AA (now FCS) past: a ramshackle stadium without a press box or permanent bathrooms; off-site coaches offices; and rosters primarily drawn from in-state players in the talent-poor Bay State.

“It was almost like when you buy a house you can’t afford—that was UMass,” said Molnar. “We had this big aspiration to live in the fancy neighborhood but not necessarily all the resources in place and all the alignment in order for it to happen.”

Almost none of the key individuals responsible for pushing UMass into and keeping it in FBS remain at the university. Holub died in 2023. His successor, Kumble R. Subbaswamy, the physicist who served as the school’s 11th chancellor and repeatedly beat back faculty-led efforts to revisit the decision, retired in 2023. McCutcheon, the athletic director who oversaw the transition, left UMass in 2015 to become AD at UC Santa Barbara, retiring there in 2021. (Neither Subbaswamy nor McCutcheon responded to numerous requests from Sportico.)

Lacey, for his part, finished his second term on the faculty athletic council in 2014, though he continued to advocate for FBS membership, and retired from his professorship in 2021.

“Go in with your eyes wide open,” said Lacey, when asked what lessons can be learned from UMass. “Back then, there was still a hope you could get a coach and a couple good players, and you might win some games and create some good buzz about the university. But, realize you need to put a time limit on it. You need to say this is an experiment we are going to take a close hard look at for X years, where X should be no more than five to 10 years.”

In late September, Bamford unveiled a new commitment to football, including a $25 million, three-phase renovation of McGuirk that will be financed via various avenues. That came on the heels of the buyout paid to leave the Atlantic 10, the school’s previous conference, and renovations to the locker room in the football performance center.

According to its NCAA-mandated financial disclosures, UMass spent $11.57 million on football in 2023-24, ranking 93rd out of 106 FBS public universities, but still placing its pigskin purse in the upper half of MAC schools. UMass’ first-year coach Joe Harasymiak, who previously served as defensive coordinator for Rutgers, is currently the highest-paid head coach in the MAC, according to data compiled by USA Today. Bamford said its revenue sharing and NIL overlay is also among the highest in the league.

“The three most important things, which I’ve told to our trustees and our chancellors,” Bamford said, “are that we have to recruit and retain a talented coaching staff, we have to recruit a talented student-athlete base with a healthy NIL program, and the third thing is our infrastructure. We have to invest there to be better.”

Lacey cautions against revisionist history. While he concedes that faculty naysayers may have always been right about the folly of FBS, he argues they were wrong in other respects. For example, the critics’ notion that the university could have redirected money from football to other priorities, he says, is a canard. He also notes that the competitive landscape has turned on its head since the early 2010s, upended by conference realignment, the House v. NCAA settlement and the freewheeling transfer portal.

“The faculty are tough to deal with here,” he said. “We have a lot of loud outspoken people—good people, whose heart is in it—but they are fighters and are willing to say things like, ‘Hey, we shouldn’t have some (academic departments) that are twice as big as others.”

As part of its original football-only membership agreement with the MAC, the school agreed to undertake a series of improvements to McGuirk Stadium, namely a new press box, which became a major source of frustration for Molnar. “We needed to tear the stadium down and build a new one,” the former coach said. “But if you put a new press box on that side, you are now committed to 25 to 50 more years of that stadium.”

Molnar wasn’t the only one concerned about wasted money.

In December 2011, coinciding with the move to FBS, the UMass faculty senate convened an ad hoc committee “to monitor and evaluate the costs and financial impacts of FBS football,” co-chaired by Lacey and architecture professor Max Page, the latter of whom persistently lobbied for the faculty to repudiate the transition.

That repudiation, in the form of a non-binding vote to “immediately reconsider” joining FBS, failed by a 19-18 margin in early 2013, after repeated appeals from then-chancellor Subbaswamy to stay the course. The vote took place while Page was out of town at a conference, thus forcing him to abstain. Page, now president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, did not respond to emails seeking comment for this story.

During a faculty senate meeting in September 2013, Subbaswamy and Page clashed over football, with the professor saying the chancellor had breached his public pledge not to let the school’s investment in football undermine education.

In December 2013, the ad hoc football committee put out an interim report, noting the athletic department’s financial projections were already falling short of reality. For FY12, athletics had estimated the football program would spend $4.39 million, with $3.15 million coming via main campus in the form of direct support, student fees and out-of-state waivers. In practice, the actual budget totaled $5.98 million, with $4.97 million funded by institutional support. Speaking last week, Bamford called the initial projections a “miscalculation” and “pie-in-the-sky.”

Football stadium improvements initially projected to cost $30 million in 2011 were revised upward to $36.3 million by 2013; including interest on the 30-year debt used to fund the renovations, the total estimated cost would be at least $65 million.

Meanwhile, on the field, the Minutemen finished 1-11 in the 2012 and 2013 seasons under Molnar.

The ad hoc committee’s interim report took note of what it referred to as the “more knotty issues.”

“There remains great uncertainty about intangible benefits or costs associated with fielding an FBS program,” the report concluded. “How much does the campus benefit–in applications and donations–from the greater exposure that comes with playing in the FBS? Does it hurt the financial picture to win just two games in two years?”

Molnar was replaced in 2014 by Mark Whipple, who led UMass through its I-AA glory years from 1998 to 2003 but struggled to recapture that success.

Around that same time the university made a critical decision. When the school’s football program originally joined the MAC, UMass agreed to either join for all sports after four years or exit the football agreement. When the MAC offered that full-time slot, the university declined, choosing to keep its basketball teams and most other programs in the A10 while playing football as an independent. The Minutemen stayed in that limbo for nine years, without any conference media distributions and forced to concoct an annual football schedule from scratch.

“That lack of a conference really hamstrung us,” Bamford told Sportico.

Relocating to Gillette Stadium, home of the New England Patriots, did little to attract the crowds UMass had hoped for. (Photo by Jim Rogash/Getty Images)

Faculty led by Page continued to press their case against FBS membership, leading to a vote in April 2016 on a resolution to “urge” Subbaswamy to drop down to FCS. That year, UMass directed $37.2 million in support and student fees to the athletic department, a 40% jump from three years prior. Subbaswamy reportedly sent a letter to the senators prior to the vote, urging them to oppose the measure. It failed 26-14, and no similar motion has occurred since. Subbaswamy dismissed the effort as the final grumblings of a small group of malcontents, while insisting that UMass football, despite yet another losing season, was “in good shape” and headed in “the right direction.”

There were relative glimmers. UMass managed to claw its way to four-win campaigns in 2017 and 2018—a season that began with Whipple being suspended after he publicly likened an unfavorable officiating call to “rape.” The coach was shown the door by November 2018.

In Whipple’s stead came Florida State offensive coordinator Walt Bell, billed as a young, energetic reboot. By 2021, following a 1-8 record and an embarrassing homecoming loss to FCS visitor Rhode Island, Bell was dismissed. UMass once more returned to a familiar face: Don Brown, who like Whipple, had steered the Minutemen to multiple winning seasons in their FCS era but could not recapture past success.

Brown was fired with two games left in the 2024 season, and replaced by Harasymiak, the 39-year-old rising coordinator, who, while not a UMass grad, played college ball in the state at Division III Springfield College. In announcing its fifth new head football coach since joining FBS, the school leaned on the idea that, at long last, the football program, the university and the stars were finally aligned.

“This isn’t the same old UMass,” Bamford declared 11 months ago. They haven’t won a football game since.