Every so often, a football pundit goes viral for laying into the ‘new words’ the game has developed in recent years. Usually, this is accompanied by accusations that managers or journalists have ‘swallowed a dictionary’, or indeed ‘swallowed a laptop’.

Often, the pundit gets himself in a mess trying to explain that there’s no need for the word because, back in his day, they used to call it something different (often using several words rather than one, which only serves to underline the case for a new word).

But football terminology has always evolved. Read accounts from the middle of the 20th century and you find annoyance that the word ‘striker’ is creeping in. ‘Midfielder’ was accepted relatively recently by some publications (on the basis that ‘midfield’ is not a verb, and so you can’t add ‘-er’ as you can for defend or attack). Even the concept of red and yellow ‘cards’ was vaguely controversial at one point — some magazines insisted on referring to them as ‘discs’.

And ultimately, the evolution of football language is tied to the evolution of the game itself. The introduction of new words over the past 25 years shows how the game has become more scientific, more technological and more tactical. Maybe that, rather than the vocabulary itself, is what pundits are truly complaining about.

So, after ‘ragebait’ was named the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year for 2025, here’s a look at what footballing equivalents might have been throughout the 21st century. The word doesn’t necessarily have to have been invented in that year — although it’s ideal if it comes out of nowhere — but merely popularised and exploded into the wider consciousness that year.

2000: Prawn sandwich brigade

Amid concerns over ticket prices, increased space given to corporate hospitality and the declining atmosphere at matches, Manchester United captain Roy Keane inadvertently invented a new phrase in a rant about his club’s home support.

“Some people come to Old Trafford and I don’t think they can spell football, let alone understand it,” he said. “At the end of the day, they need to get behind the team. Away from home, our fans are fantastic; I’d call them the hardcore fans. But at home, they have a few drinks and probably the prawn sandwiches, and they don’t realise what’s going on out on the pitch.”

Roy Keane, centre, versus seafood in bread was a big talking point in the 2000-01 season (Alex Livesey/Allsport)

It went, in 2000 terms, viral. This is one of those phrases that has been distorted; Keane obviously didn’t use the word ‘brigade’, but somehow this became automatically attached to the other two words, best evidenced by David Moyes’ post-match comments after a 1-0 win over Arsenal in his brief spell in charge a decade later. “The crowd played a massive part today,” he said. “There was certainly no prawn sandwich brigade here today.”

It now feels a little dated — even if it was recently used in a Daily Mail headline — because corporate hospitality is now so luxurious you’d expect more than prawn sandwiches.

2001: Fox in the box

This brilliant phrase for a lively goal-poacher was seemingly invented by accident.

In his biography of Thierry Henry, French journalist Philippe Auclair explains that it was unwittingly co-authored by himself, Thierry Henry and the late Evening Standard journalist Steve Stammers in the aftermath of Arsenal’s FA Cup final defeat in 2001 at the hands of Liverpool. Arsenal had dominated the game, but lost the game thanks to two opportunistic Michael Owen strikes. Henry, ruing Arsenal’s lack of a player in that mould, suggested to assembled French journalists that Arsenal needed a ‘renard de surface’.

Stammers asked Auclair how that translated. Auclair explained. It happened to rhyme: fox in the box. Immediately realising it would make a great headline, Stammers asked Auclair not to tell anyone else until he could get it written up and in the paper.

It briefly became a common phrase, most associated with Francis Jeffers, signed by Arsenal from Everton to be that player a month after the FA Cup final. The phrase itself was more successful than Jeffers.

2002: Metatarsal

When David Beckham’s World Cup 2002 campaign was threatened by a tackle from Deportivo’s Aldo Duscher in a Champions League tie, we were introduced to an unfamiliar word: the metatarsals, the bones at the top of the foot. Football had, subtly, become more scientific. What was once a mere ‘twisted ankle’ would increasingly be referred to as an ‘ankle ligament’ injury, but ’broken metatarsal’ sprang up from nowhere.

“It used to be called a broken foot,” said then-Reading physio Jon Fearn a couple of years later, speaking to the BBC. “After all the Beckham analysis in 2002, the metatarsal word came up and has been used ever since.”

Traditionally, English football has been more vague with injuries than other countries, particularly Spain. Last year, for example, The Athletic headlined a piece about Alexis Putellas’ fitness problems with simply “leg injury”, while the information from the club was that she had suffered a “triceps surae” problem. The halfway house of ‘calf’ is probably what most of us are looking for.

2003: Active

You could populate half of this list with various offside-related phrases: daylight, armpit, T-shirt line.

The craze in 2003 was ‘active’ (and ‘passive’). This was essentially an acknowledgement that a player in an offside position was not actually offside unless he was attempting to play the ball, or blocking an opponent.

It’s quite standard now, but it caused confusion, with some players — most notably Manchester United’s Ruud van Nistelrooy and Bolton Wanderers’ Kevin Nolan — taking advantage by standing offside at free kicks, waiting for defenders to ‘drop’ and then becoming involved if the ball was half-cleared.

“This rule is absolute nonsense,” said Match of the Day pundit Alan Hansen. “What is passive or active? What is second phase? Do me a favour. I just shake my head now and cannot believe what is going on.”

2004: Parking the bus

When Jose Mourinho complained about Tottenham Hotspur’s negative tactics in a goalless draw with his Chelsea side a couple of months into his period in English football, he borrowed a phrase from Portuguese.

“As we say in my country, they brought the bus and they left the bus in front of the goal,” he said. Clearly, this was a bit wordy, so this became ‘parking the bus’, which initially found popularity as an insult for unambitious football, then later was used in a more neutral manner to mean deep defending.

Mourinho, ironically, became one of the managers most regularly accused of parking the bus.

2005: Bouncebackability

A year beforehand, when Iain Dowie suggested that his Crystal Palace side had proven their ability to recover from a disappointing result and respond with a victory, he was presumably slightly flailing for the right word to use.

But that’s precisely why words should be invented, and after a campaign by Soccer AM for the word to officially enter the English language, it increasingly became used knowingly by sports commentators, journalists, and eventually the wider world too. Ultimately, Soccer AM got its wish.

Justin Crozier, director of the Collins English Dictionary, explained: “Bouncebackability came to our attention in September in our huge database of words. We thought it would die out but it steadied in October, and exploded in November. It went into a life of its own then. I can see why it works. It has a nice rhythm to it as a word, and it also sounds punchy.”

Iain Dowie, creator of bouncebackability (Ian Walton/Getty Images)

2006: Fanzone/fanfest/fanmeile

Forgive a quick detour over to Germany, but this concept deserves special recognition here because ‘fanmeile’ — fan mile — was literally named the German word of the year for 2006.

In the summer, when Germany hosted the World Cup, city centres hosted huge parties, often across extraordinarily large areas. The Berlin one supposedly contained a million people for a quarter-final penalty shootout victory over Argentina, in the shadow of the Brandenburg Gate.

It was the first time FIFA had officially designated city centre areas as ‘fanfests’, which are now more commonly known as ‘fanzones’, but regardless of the precise wording, there was suddenly the requirement for a new noun.

2007: Transitions

During this next period, football language advanced significantly in tactical terms.

Now a common phrase, ‘transitions’ were barely heard of before the mid-2000s — as evidenced by Damien Duff, a key winger in Jose Mourinho’s first Chelsea side, recalling the manager’s instructions to the side.

“Mourinho was big on transitions,” he said. “It was probably the first time I’d heard it. If you lose the ball, it’s transition from defence to attack, everyone getting back into position. On the other hand, if you win the ball, it’s transitioning into attack, exploding forward quickly.”

A buzzword in coaching circles for a few years beforehand, it became more common after Mourinho’s back-to-back title successes, and felt established by the time English football became overwhelmingly based around counter-attacking.

2008: Tiki-taka

This is generally credited to Javier Clemente, who was Spain manager in the mid-1990s but is most associated with a successful stint with Athletic Club the previous decade. Oddly, Clemente intended it as a term of derision for fruitless, pointless possession play that didn’t go anywhere; his style of football was about getting the ball forward quickly.

But when Spain passed their way to Euro 2008 victory — as it happens, under another old-school manager, Luis Aragones, who adapted his approach to suit Spain’s best players — the term became recognised in England to refer to possession-based football.

By this point, the term was generally used positively. Later, when teams were perhaps too focused on possession, it became more of a negative again and even Pep Guardiola wanted to distance himself from it. “I hate tiki-taka. Tiki-taka means passing the ball for the sake of it, with no clear intention, and it’s pointless,” he said in Marti Penarnau’s book about his time with Bayern Munich.

“Don’t believe what people say — Barca didn’t do tiki-taka!”

2009: False nine

The concept of a notional centre-forward (or ‘No 9’) dropping into deeper areas has a long and storied history, and you can find uses of the word ‘false’ in this context as long ago as the mid-1980s.

But in modern terms, Francesco Totti’s role at Roma led to the term being popularised in 2006-07, Cristiano Ronaldo’s period up front for Manchester United led to an increased usage (it’s strange to think Ronaldo was once considered in this mould) but then Lionel Messi’s role for Barcelona towards the end of the 2008-09 treble-winning campaign meant it became acceptable to use the phrase without quotation marks.

Francesco Totti… captain, leader, false nine (Alberto Pizzoli/AFP via Getty Images)

2010: The Poznan

In a World Cup year, the Jabulani and vuvuzela have serious claims to this title. But something that happened later on in 2010 has had more of a legacy: Lech Poznan fans turning their back on the match, linking arms, then jumping up and down. Manchester City fans adopted it after a contest between the clubs, and have done it regularly since.

It also became a regular feature of Oasis gigs this summer — their first in 16 years, and therefore their first since City fans started doing it. Noel Gallagher described it as the highlight of the tour, and received a shirt from Lech Poznan by way of thanks.

“We are truly proud that such a great club as Manchester City helped to spread the name of our city and team in such a remarkable way,” their letter read. “We’ve seen the recordings from your concerts where you encourage Oasis fans to join in and do ‘the Poznan’ — and we have to say, it really makes a huge impression.”

2011: Underlap

These days, this is a perfectly acceptable word when a full-back runs inside a winger who is in possession, rather than the traditional run, the overlap on the outside. But when Chris Coleman said it during a brief run as a Sky Sports co-commentator in the post-Andy Gray period, Twitter exploded.

It stuck — and a niche word for a niche action has become a standard word for an increasingly standard action.

Did Chris Coleman just say ‘underlap’ to describe a full-back running past a winger on the inside?

— Jonathan Wilson (@jonawils) March 6, 2011

2012: Tifo

A strange one, this. By now, it’s established that this means a banner or a choreography from supporters, and clearly comes from the Italian word ‘tifosi’, meaning fans.

But Italians don’t use the word. There is an English-language Wikipedia entry for ‘tifo’, but not an Italian-language entry.

Somewhat mysteriously, it entered popular usage without any real logic. The Guardian used it in a headline in 2012, but also felt compelled to include a hyperlink on the first mention of the word in the article itself, linking to an explanation.

2013: Raumdeuter

A phrase invented by Thomas Muller about himself. A curious player, not overwhelmingly elegant or physically remarkable or technically outstanding, Muller found fame as a right-place-at-the-right-time merchant who wasn’t even a pure No 9 in the Filippo Inzaghi mould. He wasn’t obviously a right-winger, or No 10 either.

What he was, Muller suggested, was a “raumdeuter”; a clever pun on the German word “traumdeuter”, which refers to an interpreter of dreams, and therefore essentially means an interpreter of space. It entered into wider usage during Bayern’s run to European Cup success in 2013, and became semi-official when Football Manager allowed gamers to assign this specific tactical role to a player.

2014: ‘We go again’

Steven Gerrard’s post-match rallying cry after Liverpool’s 3-2 victory over Manchester City is chiefly remembered for his somewhat unfortunate. “This doesn’t slip”, which inevitably became a running joke when Gerrard cost Liverpool the title by slipping in a subsequent game against Chelsea. But another phrase in that speech — “We go again!” — has become a standard phrase in football.

Interestingly — presumably because Liverpool’s campaign ended in agony for Gerrard — the phrase is now generally used after defeat, as if to encourage some level of, well, bouncebackability. Gerrard wasn’t originally using it in that manner; he was encouraging Liverpool to maintain the same standards after a win.

But, for example, when Liverpool dropped points against Leicester City in a closely fought title battle with Manchester City in 2019, Jurgen Klopp used the phrase in what has become the accepted context. “Everything is fine. I don’t think anybody was injured, and now we have a few days to prepare for West Ham, and we go again.”

2015: Gegenpressing

Regaining possession immediately after it has been lost. This was initially popularised in German football, and became particularly common around the time Klopp’s Borussia Dortmund side were winning back-to-back Bundesliga titles. Meanwhile, German football analysts were suggesting that England’s lack of an equivalent word was not a mere linguistic shortcoming, but a tactical failing too.

It exploded into wider usage once Klopp took charge of Liverpool; it could simply be called counter-pressing in English, but gegenpressing is a nod to the fundamental importance of this tactical concept in German football.

2016: Free 8s

When Guardiola arrived at Manchester City, he redeployed Kevin De Bruyne and David Silva — previously competing for the No 10 role in a 4-2-3-1, with the other forced to play from wide — as dual ‘No 8s’ in a 4-3-3. They were given the licence to push on from central midfield into the channels and make runs behind the opposition’s defence.

“It’s a different role,” De Bruyne told the Belgian newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws. “It’s all right. It’s a little change, but it’s all right. The coach has his own tactics. I play not as a No 10 but as a free No 8 with a lot of movement everywhere.” Like Muller, by christening his own role, he’s become synonymous with it.

How to fit two ‘No 10s’ into your team? Make them ‘free’ No 8s, of course (Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images)

2017: Remontada

Previous foreign words entered into popular usage because there was no English equivalent. ‘Remontada’ is an outlier, because it simply means ‘comeback’.

There’s no obvious reason it became so prevalent (there is, at least, logic to ‘cojones’, because the English equivalent is a swear word) but it’s a lovely word to say, so when Barcelona overturned a 4-0 first-leg defeat to Paris Saint-Germain with a 6-1 second-leg win, everyone was happy to say the Spanish version.

Still, even the English only ever seem to say it in relation to Spanish sides, which seems right.

2018: xG

When Match of the Day started displaying ‘expected goals’ figures alongside ‘shots on target’ and ‘corners’ after highlights of each match throughout 2017-18, the programme was unusually ahead of the curve.

There was inevitably a backlash — the phrase isn’t a particularly intuitive one — but gradually everyone realised that it was, in basic terms, a ‘shots’ figure, adjusted to account for the position of the shot. xG is surely the most nerdy phrase that has entered popular usage, and marks the beginning of the period of more mathematical and technological words being used.

2019: VAR

Introduced at the World Cup the previous year, but in the Premier League for the 2019-20 season, when it really took off.

Oddly, there remains something of a confusion about two things. First, whether this is an initialism or an acronym, and therefore whether it is pronounced ‘var’ or ‘v-a-r’.

Second, whether VAR refers to the technology being used, the official controlling the technology, or both.

2020: Burofax

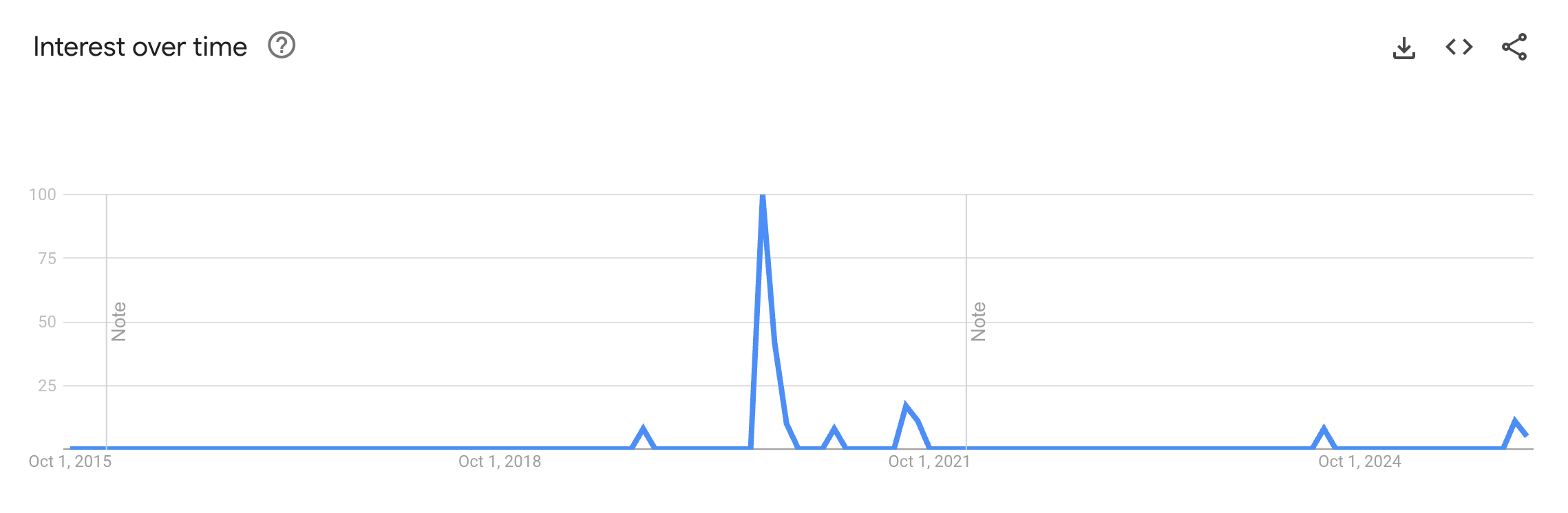

When Lionel Messi effectively handed in a transfer request at Barcelona in 2020, he did so using a ‘Burofax’, a word that had barely been heard outside Spain, and had no obvious translation.

This prompted everyone from AS to the Sun to USA Today to publish articles simply asking, ‘What is a Burofax?’, to which the answer was: a recorded delivery of a document that is certified by the Spanish postal service, and could be used in court to prove the receipt of the delivery.

Granted, no one has had much need to use it since, but Google Trends reveals the extent to which, for a week, this was the most searched-for word in football.

2021: Draught excluder

2021: Draught excluder

Until the 2020-21 season, few people had ever thought to put a player lying ‘underneath’ a jumping wall at a free kick. Then, suddenly, everyone was doing it. And therefore it needed a name.

English football went for ‘draught excluder’ — seemingly first used on Sky Sports by Alan Smith and promoted by his long-time commentary partner Martin Tyler — after the objects placed under doors to stop cold air getting in. Other countries, which seemingly have properly insulated houses, have less requirement for such devices and went for ‘crocodile’ or ‘railway barrier’.

This was important enough to be put to a vote by The Athletic in May 2021, which dates this nicely.

2022: Sportswashing

There are various instances on this list where the concept has been around for decades, but the actual word was coined a few years before it became uttered more than ever in a certain year.

And so 2022 kicked off with a Guardian article simply entitled, “Could 2022 be sportswashing’s biggest year?” This was largely because of that year’s World Cup in Qatar, but also because of Saudi Arabia’s takeover of Newcastle United towards the end of the previous year, and the ensuing debate over club ownership.

Midway through 2022, for example, it was announced that Newcastle’s away kit would be in the colours of the Saudi flag.

Newcastle’s 2021 takeover led to ‘sportswashing’ entering the Premier League lexicon (Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images)

2023: PSR

Unquestionably the most boring phrase on the list — short for profit and sustainability rules, which suddenly became a major talking point when Everton were deducted 10 points in the November. Subsequent points deductions followed for both them and Nottingham Forest in 2024.

2024: Swiss model

The concept of a league table where, unusually, everyone doesn’t play everyone else — and therefore is a genuinely new concept to most football supporters.

Originally termed the Swiss league, Swiss model or Swiss format, the new Champions League format is officially known as the league phase, but it feels odd to refer to a ‘league phase’ in a whole competition called the Champions League, and therefore the older phrase has become relatively standard.

Besides, it’s not a typical league phase, and therefore, when discussing the success and popularity of the new format, you do need a specific word.

2025: Finishers

It has been a few years since some clubs started referring to substitutes as ‘finishers’ — Michael Walker’s article for The Athletic in 2021 focused on the concept at AFC Wimbledon — but it has particularly exploded this year.

It was used regularly by Sarina Wiegman throughout England’s successful Euro 2025 campaign. Cerys Jones’ article midway through the tournament was entitled “Should any of England’s finishers be starters in the final?”, the first instance of The Athletic using the word in a headline without quotation marks, although in the article itself she felt compelled to use “so-called ‘finishers’”, the telltale sign of a word on the cusp of mainstream acceptance.

There is a logic to the phrase in itself and why it’s taken off only recently.

First, ‘finishers’ makes those players seem more involved than mere ‘substitutes’, which sounds distinctly second-class. Also, the advent of five substitutes means that these players are more likely to get on the pitch; football is more of a squad game than ever before. England’s ultimate finisher, Chloe Kelly, became the Lionesses’ latest contender for Sports Personality of the Year despite not starting a single game.

Chloe Kelly, football’s ultimate ‘finisher’ (Julian Finney/The FA via Getty Images)

The frustrating thing, of course, is that ‘finisher’ already means something else in football. A ‘good finisher’ is traditionally someone who reliably takes goalscoring chances. Therefore, if you were to describe Liverpool’s Wataru Endo (who made one start, 19 substitute appearances and attempted zero shots for the champions last season) as a ‘finisher’ a few years ago, you would be laughed out of the pub. In 2025, he’s the prime candidate for the new interpretation of the word.

The only alternative opposite for ‘starter’ would be taking ‘end’ rather than ‘finish’ as the root and calling them ‘enders’; it’s a shame this doesn’t sound right, as Endo the ender has a nice ring to it.