This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering the mental side of sports. Follow Peak here.

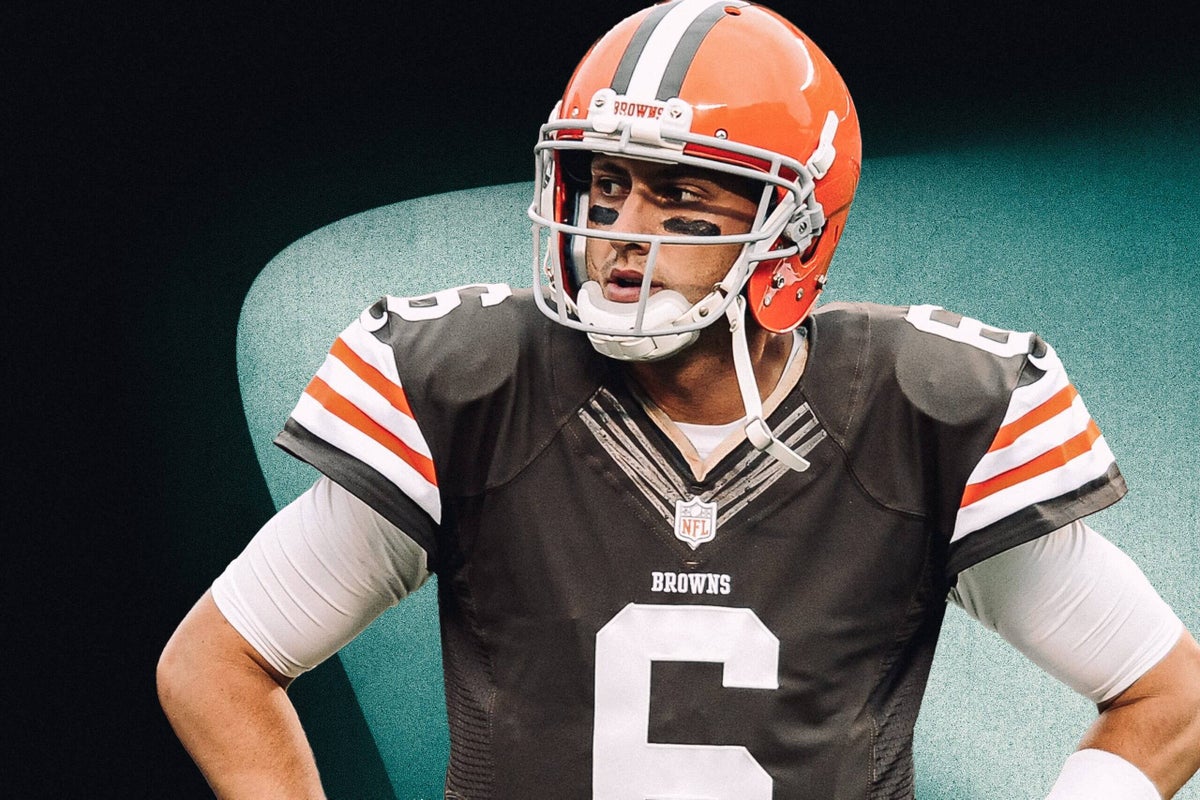

Brian Hoyer played 15 seasons in the NFL for nine different teams.

You could feel the energy around town.

It was my third week starting at quarterback for my hometown team, the Cleveland Browns. We played the Buffalo Bills at home on a Thursday night game in 2013, and there was a lot of hype because we’d won two games in a row.

In the first half, I’ll never forget scrambling to my right and trying to get one of our receivers to go deep because there was a void in the defense. But he wasn’t able to get there so I just ran.

I slid and my back cleat got stuck in the ground at the same time Bills linebacker Kiko Alonso hit me. I stayed on the ground after the play, but my knee didn’t hurt at all. I actually thought I hurt my hip.

I walked off the field to the locker room. The Browns did some tests and X-rays, and I was sitting in the training room when the team doctor came over and told me the news.

“This has all the signs of a torn ACL,” he said.

I was very upset, breaking down and shedding some tears, which was rare for me. I felt like I had finally gotten my break. This was my first chance to really start in the NFL, and it was for the team I grew up cheering for. I was living the actual dream. And then, all of a sudden, it was ripped away from me.

Believe it or not, I had gone my entire athletic career without a significant injury. That was the tough part of the injury mentally: Why now? Why is this happening now? Couldn’t it have waited two years until I had established myself? I knew the grueling grind it was going to take to get back, but I didn’t know if I would ever get back. Nothing was guaranteed at that point.

I sat there in the locker room and Joe Banner, the Browns’ CEO, came down and checked on me. At halftime, a bunch of the players and coaches came over to check on me, too. I sat there and thought about what the next eight months would hold. I just didn’t know.

The physical pain of football is something you sign up for. But the heartbreak isn’t.

To throw another wrinkle: My wife was due with our second child at the time. We had scheduled an induction for a Tuesday later that month because it was an off day. My daughter was born on Tuesday, Oct. 15. I spent one night at the hospital, came home, spent a day together as a family and then I went into surgery early on Friday, Oct. 18.

By Sunday morning, I was starting rehab: stretching and mobility exercises.

I couldn’t drive, so every morning someone picked me up and drove me to the Browns’ facility. Every day was four to six hours of rehab. Psyching yourself up every day to do something that you know is going to be painful is not easy. It was also monotonous work.

I tried to attack rehab like I was preparing for a game. I told myself: You’re working toward something. It’s just going to take a while. And I tried to find the competitiveness in rehab.

Before my surgery, the Browns took measurements of my quad muscles and strength to establish the baseline. So each day I had something to shoot for. One of the biggest things is trying to get your flexion back, which is the bending of your knee. And every day I would not leave rehab until I got at least one more degree of flexion. Even if it seemed small, it was one of the only things I could see progress in.

When I hit one of those little milestones, I felt better.

I had just tasted what I was trying to get — a starting job in the NFL — and it motivated me each and every day to push myself to a different level. Then, to kick it into high gear, the Browns drafted Johnny Manziel in the first round right in the middle of my rehab. I was like: OK, I’ve got to get back even faster.

I probably drove Joe Sheehan, the Browns’ trainer, nuts because with each progression I’d tell him: “I can do more. Let me do more.” On Halloween, 13 days after surgery, I walked around our neighborhood with a knee brace, taking my son trick or treating. On Christmas Eve, I was running on a zero gravity treadmill. I pushed myself to the limits.

Joe lived not too far from me, and I’d ride my bike by his house to see if he was outside, just so I could show him that I was fine and that I was ready to practice.

Every single day I tried to come to rehab with the mentality that “I’ve got to get just a little bit healthier today, even if it’s going to suck.” We all face adversity in a lot of different ways. I was primed for it. My career started off with adversity. Didn’t get drafted, made it as a backup quarterback to Tom Brady with the Patriots, got cut in New England and was out of football for 10 weeks. This injury was another thing to overcome.

I played in New England for Bill Belichick. Every day was adversity. He created it that way, and that’s why those teams were so tough. At some point, the mental side takes over the physical. If you don’t have that, you’re going to break. During rehab, I drew on that experience.

I was back in training camp the following year and had my first “oh shoot” moment. Quarterbacks aren’t supposed to get hit in practice, right? Well, there was a play in training camp where I got drilled in my lower half. My first thought was to check if my knee was OK after taking that hit. Once I got past that moment, I was thankful for it because I felt confident again.

In hindsight, one thing I can say for sure: Although I wouldn’t wish this injury on anyone, grinding through that long rehab made me mentally tougher.

— As told to Jayson Jenks