Over the course of this year, The Athletic has met up with seven footballers born across a period of 70 years, from 1935 to 2005.

Between them, they have made more than 3,000 senior appearances at club level and more than 100 more for their countries. One of them can also cite more than 1,000 matches as a manager.

Part one, which introduced the seven players and primarily covers the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, can be found here.

Part two, reflecting the changes in English football over recent decades, follows.

Robbie Earle, 60, describes lower-division football with Port Vale in the 1980s as “a slog”.

“You’d be going up to Hartlepool, leaving on a leaky bus at 7am, and when you got there it would be p**sing down with rain and there’d be 2,000 people on the terraces,” he says.

“It was a tough environment. If you showed any weakness — on the pitch, in the dressing room, physically, or mentally — you’d fall by the wayside and be left behind.”

Black players, such as Earle, often faced racism — not just from the fans but opposition players and, at times, even their team-mates.

“At certain grounds, the abuse would start the moment you kicked off,” Earle says. “Not just one or two people, but whole sections of the crowd. You’d get it from older players who maybe hadn’t had much contact with people of colour.

“At Port Vale, we had a number of prominent Black players. We felt we had to use our colour to our advantage: ‘If we’re going to get stick, let’s score as many goals as we can to shut them up.’ You had to toughen up. It wasn’t going to go away.”

That was a dark period for English football. As hooliganism persisted through the 1970s and early 1980s, attendances fell to their lowest level since before the First World War. A Sunday Times article in 1985 infamously referred to football as “a slum sport played in slum stadiums, increasingly watched by slum people”.

But things were about to change. One factor was the 1990 World Cup, where England reached the semi-finals and captured the public imagination. Another was the creation of the Premier League in 1992, which led to more revenue and, in time, an influx of talent and investment from abroad.

Earle says the initial changes were superficial — “this new product that was shiny and glossy with an element of showbiz and celebrity” — but they had an effect. “People who weren’t football fans before became attracted to the game, which raised the profile,” he says. “There was a lot more media attention. It felt like it was ramping up to something.”

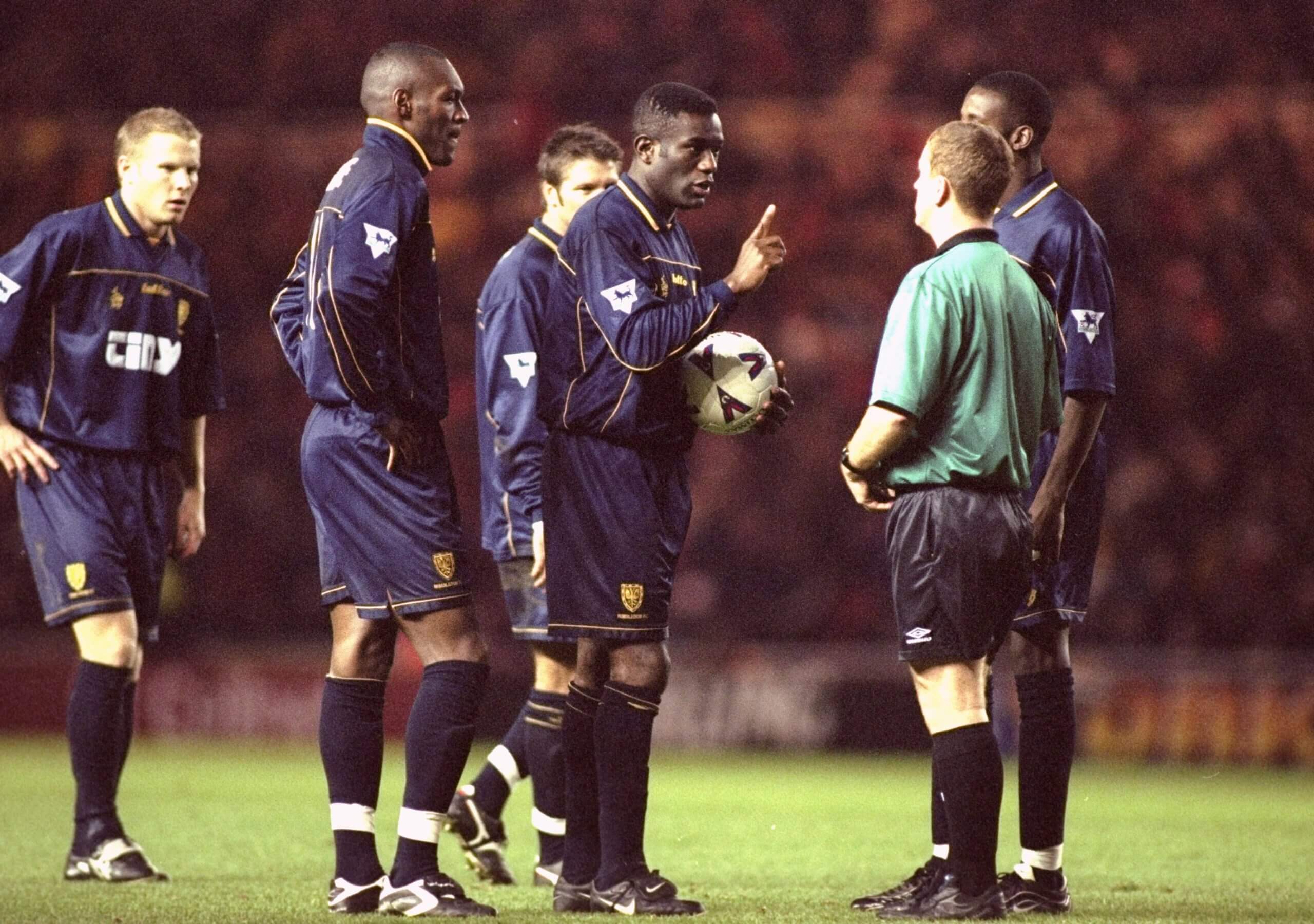

He was by then part of a Wimbledon team whose “Crazy Gang” image was unsophisticated even by English football’s standards of the time. Dressing-room punch-ups were a regular occurrence, as were impromptu bonfires if any player dared to turn up for training in an expensive suit. On Earle’s first day at the south London club, in 1991, he was stripped on Wimbledon Common by his team-mates and had to jog back to the training ground naked.

Earle played for a competitive Wimbledon side in the 1990s (Clive Mason /Allsport via Getty)

Dressing-room culture changed — even, reluctantly, at Wimbledon — but some old habits died hard.

Earle says one highlight of playing Manchester United at Old Trafford was the post-match trip to former United player Lou Macari’s nearby fish and chip shop. “This was the mid ’90s, and we were still having fish, chips and mushy peas as our post-match meal,” he says. “Football was your job, but it still felt a bit part-time-ish.

“When a lot of the foreign players and coaches came in, there was a whole new perspective on diet, sleep, training and looking after yourself. Players became more athletic, better coached, better prepared for games.”

George Boateng, a decade younger than Earle, was part of that influx from overseas, leaving Dutch club Feyenoord for Coventry City in 1997.

“When I came over, I found the technical side of the game so easy,” he says. “The Dutch league had a high level of technicality, but the Premier League was more physical, less technical. Most teams had four or five overseas players, but it wasn’t big signings like there were later. By the time I was at Middlesbrough (2002 to 2008), the level of players across the league was much higher.”

So was the earning potential. Boateng was being paid around £3,000 a week when he joined Coventry. Eight years later, with bonuses, he was making around 10 times that. “More than I ever anticipated,” he says. “And the really top players earned more than £100,000 a week.”

The sums were life-changing — sometimes for the worse. Boateng saw team-mates struggle with alcohol, drugs or gambling. Others, in some cases having been exploited or poorly advised, have been declared bankrupt since retiring. Money did not guarantee happiness.

After Billy McCullough’s football career wound down, he spent 30 years working for a lighting company. He mentions one customer seeing his name and asking, “Are you the Billy McCullough who played for Arsenal?”

That customer treated him to lunch and a big lighting order, but such instances were rare. For footballers of that era, it was easy to blend back into normal life after retirement because you had never really left it in the first place.

Billy McCullough, who played for Arsenal in the 1950s and 1960s (The Athletic)

Ian Storey-Moore, now 80, came out of retirement to play for Chicago Sting during the brief North American Soccer League boom of the 1970s. “It was an experience,” he says. “It was on astroturf, which back then was probably harder than this floor. I only played a handful of games before my ankle went again.”

He also managed at non-League level, before seeking a more stable living. “There was a small betting shop in the village and the fella who owned it sold it to me,” he says. “I didn’t make much as a bookmaker, but it was a living and I had to do it.”

Storey-Moore was grateful when former club Nottingham Forest offered him some work coaching — and then, more rewardingly, scouting. He became chief scout at both Forest and Aston Villa, where one of his first recommendations, in early 2007, was a certain 21-year-old winger at Watford…

Since that initial rejection at Watford as a teenager, Ashley Young’s career has taken him to Aston Villa, Manchester United, Italy’s Inter and Everton, as well as a World Cup semi-final with England. At 40, he is still going strong at Ipswich Town of the second-tier Championship.

Young reels off a few areas where the game is almost unrecognisable compared with its past: the social aspect, so different to his early days at Watford when “team bonding was a night out, drinking non-stop”; the improvement in training facilities, sports science and so much data that “it sometimes fries my brain”; the nature of the game itself, where “it’s a lot more tactical and defenders are on the ball more than the forwards”.

In the 2000s, the end of a season meant switching off. Young remembers seeing older players return for pre-season training and thinking, “Wow, you had a good summer.”

“No one trained for five or six weeks after the season finished,” he says. “Players ate and drank whatever they wanted and then said, ‘I’ll use pre-season to get my weight down for when the season starts’. Now people do a ‘pre-pre-season’ to get ready for pre-season. Nutrition, so many different supplements and vitamins, gym work, all the S&C (strength and conditioning) work, everything has changed.”

Young, right, playing for England in the 2018 World Cup semi-finals (Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

He is less enthusiastic about video assistant referees (VAR). “I hate it,” Young says. “What’s wrong with the old school? Referees and linesmen (assistant referees) used to make a decision and, if someone’s foot or shoulder was just a little bit over, then that’s football, you got on with it. Now you score a goal, and we all stand there waiting.”

Another big change is the media landscape. Mainstream coverage of the game has grown hugely, but over the past decade and more, social media has become a constant, and at times toxic, presence in footballers’ lives.

“It can work in your favour,” Young says. “It can also massively work against you. I’ve seen it first-hand with players who read comments from people who are nothing to do with their life and are just going to be negative. Why read it? I try to say, ‘Stay off it. Don’t read the comments.’ It can mentally ruin people, which I know it has done.”

Ashley Phillips, 20, can barely remember a world without social media.

“I try not to read it,” the Tottenham and England Under-21 defender says. “People will always have opinions, but the best thing you can do is try to ignore it and listen to those whose opinions matter.”

The upside of social media is that it brings a certain commercial profile. Phillips is yet to make his Premier League debut but already has a deal with Under Armour, which supplies his boots and other equipment.

Ashley Phillips playing on loan for Championship side Stoke City this season (Jasper Wax/Getty Images)

Leading football players, like clubs, are now global brands. Phillips mentions seeing “thousands of people at the airport” to greet the Tottenham squad on their pre-season tour of Asia last year. “Son (Heung-min, their South Korea international) had three security guards around him,” he says. “It was unbelievable.”

Phillips is among the most promising English players of a generation who, if they establish themselves at a leading team, might earn enough before retirement to never have to work again.

Such talk irks him slightly. His ambitions, as he thrives on loan at Stoke City in the Championship, are all about success on the pitch. He agrees it is a “fantastic time to be a footballer”, but he feels he would say the same of any era “because if you’re not enjoying it, why are you doing it?”

The difficulty is that, with Premier League clubs having the wealth to sign the best players from all over the world, even the most gifted homegrown youngsters are not guaranteed opportunities. “You just have to use it as an incentive to push even harder,” Phillips says, “and be that one who makes it.”

Steve Coppell was one of the luckier ones, after being forced into early retirement in 1983 by injury. He looked into going back to university before unexpectedly being offered the manager’s job at Crystal Palace the following year at age 28.

Coppell proved a natural in his new role, leading Palace to promotion into the top flight in 1989, the FA Cup final in 1990 and a third-place finish in the league in 1991. The job became harder as player power — and agent power — increased, but he went on to spend 25 years managing Palace, Manchester City, Brentford, Brighton, Reading, Bristol City and three clubs in the Indian Super League.

One summer, while Palace were on a pre-season tour in Finland, he was told that Jozsef Toth, the Hungarian defender whose wild challenge badly injured him in 1981, setting him on the path to retirement, was living nearby and would like to meet him. Coppell was in no mood for a reunion.

Steve Coppell as Palace manager in 1999 (Allsport UK /Allsport – via Getty Images)

“I used to say, very dramatically, that that fella ruined my life,” he says. “But if I hadn’t had to retire at 28, I wouldn’t have been managing at 28. I managed over 1,000 games and had some wonderful times. India was a tremendous life experience. Management was something I never planned to do, but it worked out not too badly.”

The memories are priceless, even if it turns out the memorabilia is not.

Coppell, now 70, was recently presented with the programme from his Manchester United debut 50 years ago, when his name was so unfamiliar that the club spelt it incorrectly.

Coppell thought he was looking at a precious piece of history. “I said to the guy, ‘If you told me it was worth £70, £80, £90, I wouldn’t be surprised’,” he says. “The guy had got it from eBay for £1.83.”

Management does not appeal to Young, having seen the “crazy” hours his younger brother Lewis worked during spells in charge of EFL clubs Crawley Town and Dagenham & Redbridge before taking a part-time role coaching at Watford’s academy.

“That would definitely not be for me,” he says. “To be honest, I don’t think this new generation would take to me. I’m quite old-school.”

Young intends to follow Earle down the media route. “I get more enjoyment talking about football than I would coaching,” he says.

It seems fair to suggest that, after a long career spent at the highest levels of English football in a boom period, his post-playing career will not be driven by financial necessity.

“I’m the worst person to talk about money in football,” Young says. “I’m one who says, ‘Yes, OK, I can look after my family and whatnot, but it’s about what I achieve’. That is 100 per cent my mentality.

“There’s a lot more money in basketball and the NFL, but I don’t think it’s talked about in America the way it is in England. Of course, players get paid well and drive big cars, but football is also the toughest sport to get into. It takes hard work and sacrifices that people don’t see. To play and sustain a certain level… I was going to say you’re talking about the top one per cent, but it’s probably not even one per cent.”

Young says most players regard their job as a privilege and would happily do it for far less money, but adds they are “not going to turn around say and no” when offered sums beyond their wildest dreams. “Football players have lives and families as well,” he says. “We’re human. I’m not sure some people realise that.”

After retiring due to injury in 2000, Earle worked in the UK media before relocating to the United States, initially as a commentator for the Portland Timbers of MLS. He later moved on to ESPN and is now one of the lead pundits for NBC Sports’ Premier League coverage.

He and his wife live in Long Beach, California, just south of Los Angeles — “very different”, he says, to Stoke-on-Trent in the 1970s.

He is still in touch with most of his former Wimbledon team-mates. “It’s amazing how many are still involved in the game, whether it’s management, coaching, scouting, media, agents,” he says — aware that such opportunities were scarce for those players born a decade or two earlier.

Boateng, who hung up his boots in 2013, has spent the past decade coaching, including spells back in Ghana and in Malaysia, as well as with Blackburn Rovers, Aston Villa and Coventry. Competition for head-coach jobs is fierce, but he feels he has a lot to offer and is proud of his work with RAEC Mons, who are challenging for promotion to the second tier of Belgian football.

Earle, right, now lives in the U.S. and works for NBC (Fernando Leon/Getty Images for the Premier League)

Earle would love to believe the standard of football in the Premier League was better in the 1990s, but when he stands pitchside in his media role today, he witnesses technical and physical standards far beyond those of his playing days.

He sees changing body shapes (“no more pudgy centre-backs or overweight midfielders”) but also huge advances in technique and tactical intelligence. “It’s so dynamic and so sharp, it’s like another sport,” he says. “We didn’t play at anything like this intensity.”

With that, Earle says he is off to the gym, ready to hit the treadmill “and pretend I’m still trying to chase Roy Keane and David Beckham, like in my prime”.

McCullough chuckles when it is put to him that he is in fine health for someone who has just turned 90.

“I rattle when I walk,” he says, a reference to the number of tablets he is taking. “I’ve got glaucoma, I’m diabetic, I’m getting my ear syringed because my daughter has to repeat herself when she talks to me. If it wasn’t for my daughter, I don’t know what I’d do.”

He knows he is lucky. He mentions that most of the other players in an Arsenal team photo next to him have passed away. Others are in poor health.

A 2019 study led by the University of Glasgow has indicated that former professional footballers are 3.5 times more likely than the general population to die of neurodegenerative conditions.

McCullough is not convinced there is a link between heading the ball and such diseases, but Coppell mentions his former England team-mate Dave Watson, whose dementia diagnosis has been attributed by his consultant to repeated blows to the head. Coppell remembers Watson, at the end of training sessions, standing on the halfway line as goalkeepers hit long kicks that he would meet with booming headers.

Storey-Moore reels off a long list of former team-mates who are living with, or have died from, dementia. He met two of them recently and they didn’t remember him. He is grateful to be among a group of former Forest players who meet up every Thursday to reminisce about the good old days and drink to good health.

An Arsenal team photo from 1962; McCullough, back row, fifth from left (Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

On McCullough’s 90th birthday in July, he received an Arsenal shirt, sent by the club, with his name and the number 90. “And they’d spelt my name wrong!” he says with a laugh. “I rang up and told them. They apologised and sent me another one.”

Typos notwithstanding, he still feels part of the Arsenal family. He is still in touch with team-mates such as Jimmy Magill, John Snedden and Peter Storey, all in their eighties, and is a proud member of their 100 Club, which honours every player who has made 100 league appearances for them.

There is an open invitation from Arsenal to go to a home game, but he prefers to watch on TV these days.

Certain aspects of modern football frustrate him: the way players go down demanding treatment after slight knocks (“What’s wrong with them? They’re pussycats!”) and certain playing styles (“They get to the halfway line and then they go all the way back to the ‘keeper and start all over again”) but he likes this Arsenal team. Brazilian defender Gabriel (“big strong boy”) is a favourite.

He says football has not really changed. “The ball’s still round,” he says. What has changed is everything around the game — and above all, the money. “Tell me about it!” he says.

Storey-Moore likes to watch Forest, third-tier neighbours Burton Albion and, for something more local, Carlton Town on the eighth rung of the English league ladder. Coppell, similarly, watches Palace and Brentford but gets a more regular fix at non-League sides Chipstead, Dorking Wanderers and Merstham to the south of London.

“When you’ve lived your life around Saturday 3pm, it’s hard to break away from that,” Coppell says. “That, to me, is what football is all about. Football is accused of cynicism at the highest level, but fundamentally it’s still the same game.”

And it is about creating memories.

McCullough, Storey-Moore, Coppell, Earle, Boateng and Young all have theirs, and Phillips is determined to create his in a career that is just starting out, aware that one day he will be the one looking back and telling a younger generation how much and yet how little football has changed.