As the Chicago Bears play the field over where to play, the jockeying for position brings to mind many long shots that played out in Northwest Indiana over the years – including the last time the Bears considered Northwest Indiana.

“It’s deva vu all over again,” to quote Yogi Berra.

Whether the Bears ultimately end up in Northwest Indiana, perhaps in Hammond, perhaps Gary, perhaps Portage, perhaps somewhere else, this isn’t the first rodeo for the Bears and might not be the last.

Those who have been around a while might remember the Planet Park proposal that was Northwest Indiana’s last big field goal when it came to baiting the Bears.

In 1995, Northwest Indiana-Chicagoland Entertainment – a group with a NICE acronym to remember – said the Gary acreage where the $482 million Planet Park stadium and entertainment complex was to have been developed had little pollution and could be cleaned up for as little as $12 million.

That contrasted with a 1991 study for a Gary airport expansion that found 113 acres of high-quality wetlands on the site.

The Planet Park study would have paved over 27 acres of natural wetlands; the rest of the site wasn’t studied – including what would have been stadium parking lots bordering on a federally designated Superfund hazardous waste site. NICE spokeswoman Colleen Dykes said in 1995 that most of the 27 acres of wetlands were polluted with oil, making them unsuitable for waterfowl and other wildlife.

When construction began for the runway extension at Gary/Chicago International Airport, the workers struck oil the first day on the job. The soil had to be trucked away and incinerated.

Building Planet Park would have brought a 0.5% income tax for Lake County residents to raise more than $30 million annually to back the stadium construction debt. Developers were also considering a 2% food and beverage tax.

But even that much honey wasn’t enough to attract the Bears.

Gilroy Stadium

Gilroy Stadium, near the Indiana University Northwest campus in Gary, was part of the city’s push to attract a pro football team.

In January 1955, Mayor Peter Mandich talked the City Council into building the South Gleason Park Athletic Complex. The council agreed to issue $350,000 in bonds for the stadium. Then Mandich said the city might as well do it right, rather than cheap.

Football players didn’t run on the field, but the costs sure ran up. The final bill amounted to more than $1 million, according to American Urbex, which would be about $11.9 million in today’s dollars.

Bleachers were built on the north side of the field, using 630 tons of steel to build seating capacity for 10,000. Lambeau Field in Green Bay, Wisconsin, used 11,000 tons of steel to seat 32,000 fans for Packers games.

By 1962, not only had the finances fallen apart, but the stadium was literally falling apart. Building inspectors noted cracking and moisture damage in the concrete supporting the bleachers. A federal investigation led to six individuals being convicted for kickbacks and bribes.

If the city had attracted a pro football team, it would have been in the American Football League, which merged with the National Football League in 1970 after 10 seasons, becoming the American Football Conference.

This idea was like Lucy holding the football for Charlie Brown.

Portage sportsplex

Planet Park and Gilroy Stadium aren’t the only two sports proposals where Northwest Indiana dropped the ball. Another is the Catalyst Lifestyles Sport Resort that Portage Mayor James Snyder was so enamored with.

Kyle Telechan / Post-Tribune

Portage Mayor James Snyder shakes hands with Tony Czapla, managing partner with the Catalyst Lifestyles Sports Resort project, on Tuesday, April 5, 2016, during a groundbreaking event for the Sports Resort in Portage. (Kyle Telechan / for Post-Tribune)

Catalyst Lifestyles purchased 170 acres on the city’s north side for a $75 million indoor and outdoor sports complex as well as a hotel. The land was purchased from the city’s Redevelopment Commission in May 2015 for $6 million after the city acquired it for $1.8 million over the years.

Catalyst was to make $600,000 payments over the course of 10 years.

But the project had some complications, including a NIPSCO right of way with utility towers and plans for an overpass from U.S. 12 to Ind. 249.

The partners started suing each other, stalling the project, then filed for bankruptcy twice, with both attempts denied.

The RDC took a long time to recover the property, ultimately agreeing to pay $63,000 in back taxes and interest.

The resort failed, but the RDC is being a good sport in regard to the property. It’s part of the transit development district created around the Portage/Ogden Dunes train station. Ideas under consideration for it include a lodge to serve overnight visitors to Indiana Dunes National Park, resident and commercial space, and a regional park with an amphitheater.

Marquette Greenway and Burns Parkway will be extended as well.

The game is still afoot.

Great Lakes Basin Transportation freight railroad

Another project that dreamed big until the bubble burst was the Great Lakes Basin Transportation freight railroad, intended to bypass the freight bottleneck in the Chicago area.

Frank Patton wanted to build the 261-mile freight line from Milton, Wisconsin, to LaPorte County. It was to be privately funded $2.8 billion and serve the six Class 1 railroads going through Chicago.

Michael Tercha / Chicago Tribune

Frank Patton, founder and managing partner of Great Lakes Basin Transportation, had planned a freight line from Wisconsin to LaPorte. (Michael Tercha / Chicago Tribune)

Hearings were held throughout the area, raising the hackles of residents who worried they were being railroaded.

Opponents banded together as Residents Against Invasion of Land by Eminent Domain – RAILED, another easy-to-remember acronym – to fight the plan.

The federal Surface Transportation Board rejected the plan in August 2017 in a sharply worded ruling.

“GLBT’s current assets of $151 are so clearly deficient for purposes of constructing a 261-mile rail line that the Board will not proceed with this application given the impacts on stakeholders and the demands upon Board resources,” the ruling said.

Put another way, the freight train concept ran out of steam.

Illiana Expressway

Among Patton’s ideas was to run his freight railroad along the right of way of the Illiana Expressway.

Gov. Mitch Daniels embraced the Illiana Expressway idea as a way to siphon traffic off the Borman Expressway, which is packed and can’t add lanes.

The Indiana Department of Transportation began using a few tricks this year to speed traffic along the Borman, including deciding to allow vehicles to treat the shoulder as an additional lane when there’s a crash or other incident backing up traffic and considering ramp metering – essentially stoplights on entrance ramps – to pace the traffic entering the expressway. But there’s not much else INDOT can do to add capacity to the Borman.

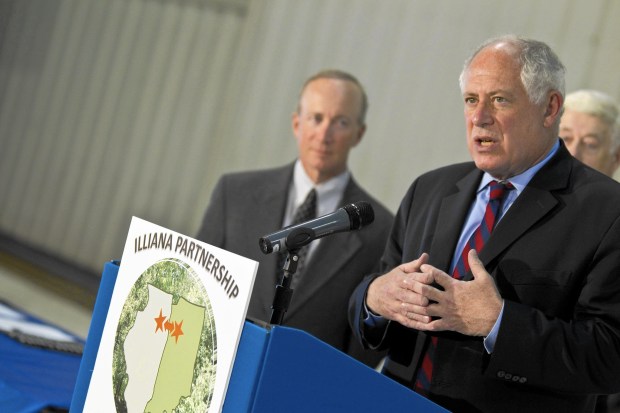

Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune

Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn, right, and Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels announce a partnership to build the Illiana expressway connecting Interstate 65 in Indiana with Interstate 57 in Illinois at a news conference in Lansing on June 9, 2010. (Zbigniew Bzdak/ Chicago Tribune)

The Illiana Expressway has been proposed for decades. It might yet be resurrected. The Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority’s new 20-year plan gives a hint that the concept is still alive, if still on life support.

As development grows in southern Lake County, though, the route for this outer ring expressway gets pushed further and further south.

Daniels paired the Illiana Expressway proposal with an Interstate Commerce Connector that would add another ring around Indianapolis for a similar purpose.

When the new South Suburban Expressway, as the Illiana Expressway is also known, went to the field hearings, though, the “not in my back yard” opposition was strong – and for good reason.

Whoever put the proposed route on the map used a fat marker to show where the route could go, making the road look far wider than it actually would be. That made it seem to gobble up more property than it actually would.

The Illiana Expressway wasn’t such a Sharpie idea, at least when Daniels strongly supported it.

Lake Calumet Airport

Gary wants desperately to be considered the third major airport serving the Chicago area despite Peotone’s intent to claim bragging rights and airline dollars.

Currently, neither city has regularly scheduled passenger service.

But the other airport that would have been the third airport shouldn’t be forgotten. The Lake Calumet Airport would have straddled the state line.

Back before there were two Chicago mayors named Daley, Mayor Richard J. Daley proposed building a Lake Calumet airport. “At any of the other sites, there are too many losers. It’s that simple,” Daley said at a December 1991 news conference.

TAMS Consultants Inc., the official consultant for the bi-state committee that was to choose the site for a regional airport, estimated the cost for a Lake Calumet airport at $17.4 billion. Daley estimated the cost at just under $10 billion.

Meanwhile, Gary officials were saying, in effect, “Hello, I’m standing right here.”

If landing a jumbo jet in Hammond and Hegewisch sounds devastating, imagine what landing an airport there would do.

Property in Burnham, Calumet City, Hammond and Hegewisch would have been purchased to build the airport.

The Whiting-Robertsdale Historical Society recounts the plan on its website. About 59 million cubic yards of sand, gravel and rock were to be dumped into Lake Michigan, 3.5 miles offshore, forming a circular dike four miles in diameter, and faced with 13 million cubic yards of stone. Lake water would be pumped out of the circle and the airport would be built on the lake’s floor.

Had the plan gone through, the airport would have opened in either 2005 or 2010, depending on whose proposal you listened to. Instead, Lake Calumet sank like a rock – or millions of cubic yards of rocks.

Ultimately, Chicago entered into a compact with Gary’s airport, changing its name to Gary/Chicago International Airport. Now the Indiana legislature is backing away from that compact, though Gary officials remain committed to the agreement.

Hovercraft highway

Late Gary Mayor Rudy Clay liked to think big. That included a proposed hovercraft – or hoovercraft, as he liked to say – between Gary and Chicago to reduce the distance for commuters. Think of it as a ferry that hovered over Lake Michigan.

The hovercraft idea is mentioned in a draft of the city’s comprehensive plan dated Aug. 1, 2008. “Offering a hovercraft ride on Lake Michigan from Gary to other lakeside attractions in Chicago, cities surrounding Gary, and to Michigan provides an opportunity for Lakeshore development,” the bullet point in that report said.

Hovercrafts were all the rage then, and they still have their uses. But traditional boats can be more fuel-efficient and easier to operate in rough water, especially when carrying passengers.

The hovercraft concept is no longer being floated.

Civil rights museum

A civil rights museum is one of Gary’s holy grails.

It makes sense to consider a city devastated by white flight as a potential site for a civil rights museum. Segregation was strong in Gary, with a hospital built to serve Blacks because they weren’t treated in traditionally white hospitals.

Then there’s the Frank Sinatra appearance that brought attention to Gary in November 1945. A lot of white students had walked out of Froebel High School when Black students began attending.

A citizens group asked Sinatra to come to their school. He stepped to the stage and said, “You should be proud of Gary, but you can’t stay proud by pulling this sort of strike,” the Chicago Daily Defender reported. “The eyes of the nation are watching Gary,” he said.

The students heeded his advice and went back to school.

The civil rights museum still hasn’t come about, but don’t rule it out. Maybe the timing just wasn’t right.

Jacksons museum

Then there’s the proposal for a museum devoted to the Jacksons, a musical family if ever there was one.

Fans across the world still flock to 2300 Jackson Street to see the postage-stamp-sized home where the large family lived. Michael Jackson was even given the key to the city with great fanfare.

But it all comes down to money. Who would pay for it? The city certainly doesn’t have extra money to build one, and even if it did, operational costs would be prohibitive.

A nonprofit would have to operate it, but who would fund it? The surviving Jacksons haven’t ponied up the money for it despite Clay’s hopes that they would.

Mayor Eddie Melton has talked about a bus tour to highlight the city’s musical history. Besides the Jacksons, the city was home to VeeJay Records, founded in 1953 by Vivian Carter and her husband, James C. Bracken. VeeJay is credited with introducing the Beatles to America along with spinning out discs for a number of acts with very recognizable names. It’s also considered one of the first African American-owned record companies.

Capitalizing on the city’s musical history might not have sung its last note.

Monorail

How about a monorail? East Chicago, Gary and Valparaiso were all mentioned as possible sites.

Clay had announced tentative deals with investors to build a monorail from Gary to points south, his June 4, 2013, Post-Tribune obituary by Andy Grimm noted.

Remember state Sen. Sam Smith, D-East Chicago? He proposed in the early 2000s that an Indianapolis and East Chicago line would work, running along 235 miles of abandoned rail lines. “When I look at the model here, what I’m seeing is a lot of steel, so you are talking about putting the men and women I represent back to work,” he said.

The nonprofit Russell Foundation supported this $10 billion private venture. Plans called for magnet propulsion, at speeds of more than 70 mph, powered by solar panels on top of the guideway and wind turbines mounted atop the support columns.

Then there’s Harry Teune, a Republican who ran for Valparaiso City Council in 1999. Teune suggested a monorail connecting what was then County Seat Plaza, where Fazoli’s now stands and Meijer is building a grocery store next year, with the downtown.

He also suggested a moving sidewalk downtown and tearing up Lincolnway to put in underground parking like in Grant Park. Or having a bridge running the length of Lincolnway for through traffic.

None of his traffic ideas made it through. And all of the Northwest Indiana monorail proposals definitely derailed.

Doug Ross is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.