Peak newsletter 🧠 | This is The Athletic’s weekly newsletter covering the mental side of sports. Sign up here to receive the Peak newsletter directly in your inbox.

Welcome back to the Peak newsletter! Thanks for all your feedback on our first edition last week. Let’s dive in…

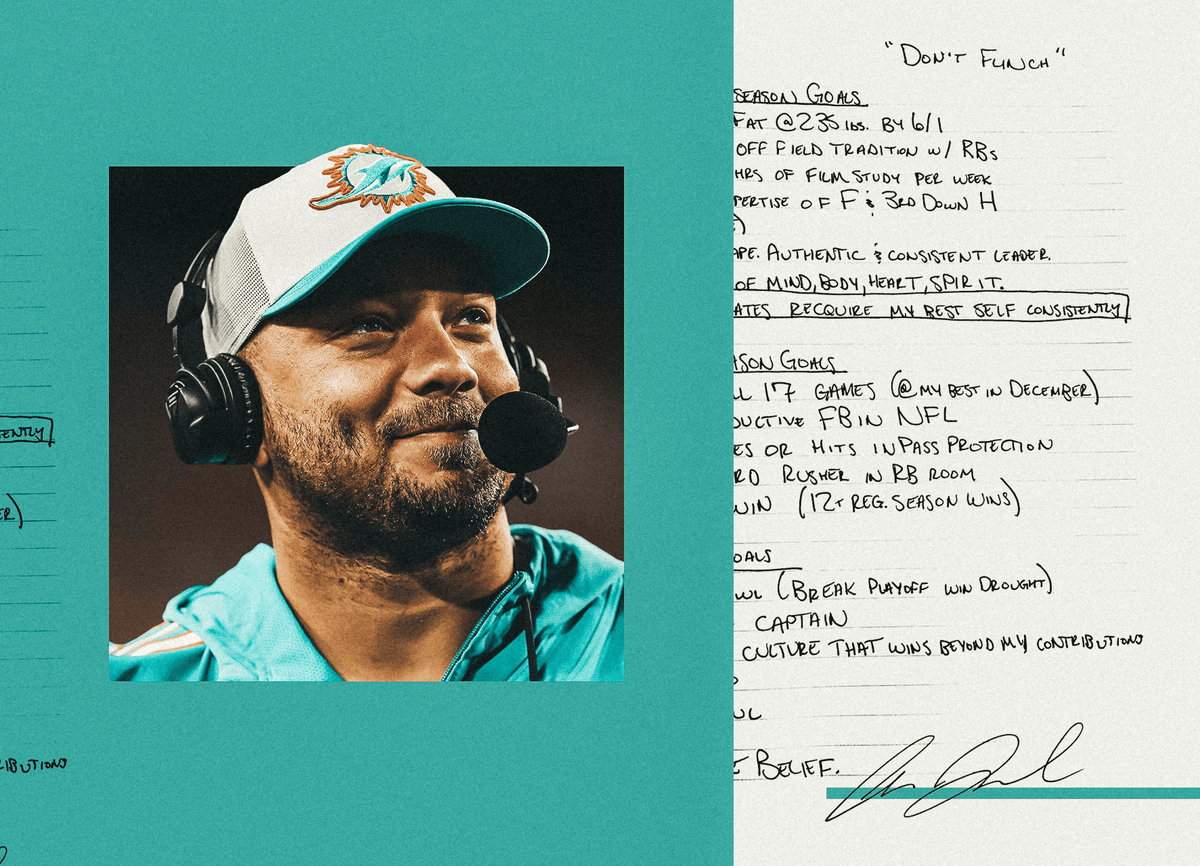

As a fullback out of Wisconsin, Alec Ingold went undrafted in 2019. Since then, he has carved out a nice career in the NFL:

One Pro Bowl (2023)

Four-time team captain for the Miami Dolphins

Seven years in the league

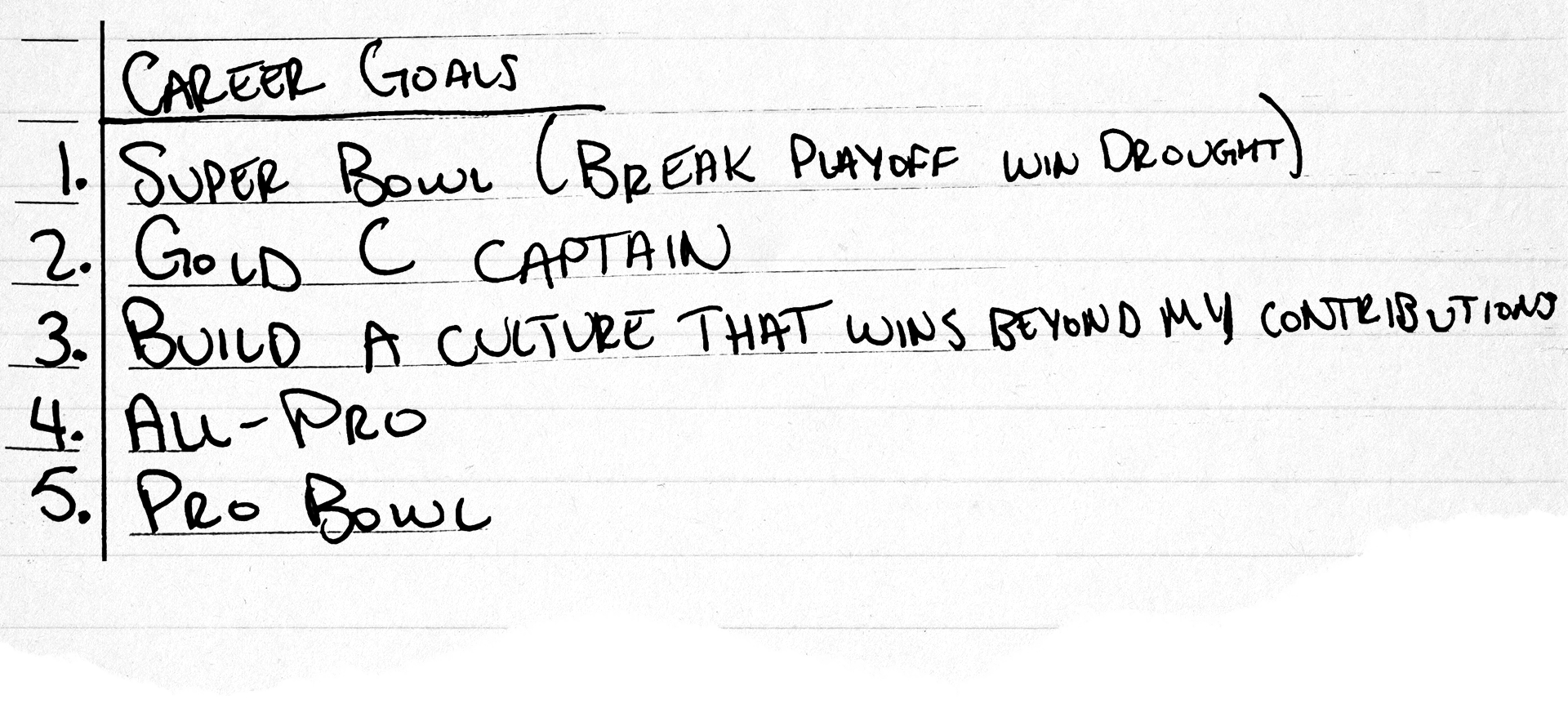

So I was pumped when Ingold shared his goal sheet for the 2025 season with Peak’s readers (after he shared his favorite motivational song with us last week!). Ingold, 29, takes goal-setting seriously — you can read more of his thoughts in this story from Elise Devlin.

For the newsletter, I asked him to break down each part of his goal sheet and explain his rationale. Very few of us can relate to an NFL player’s specific goals. But most of us can relate to the thought process behind an NFL player’s goal sheet. Starting from the top:

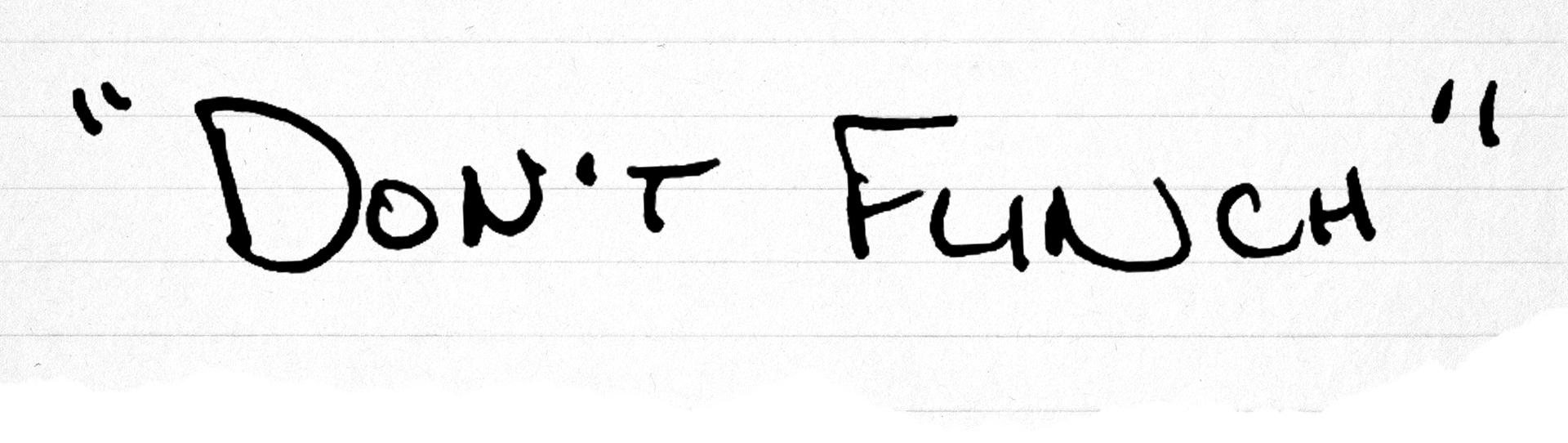

Ingold: “I wanted to attach a little self-talk to my goal sheet. When stuff gets hard or when things go sideways, don’t flinch. Do not go back on the commitment that you made to yourself.”

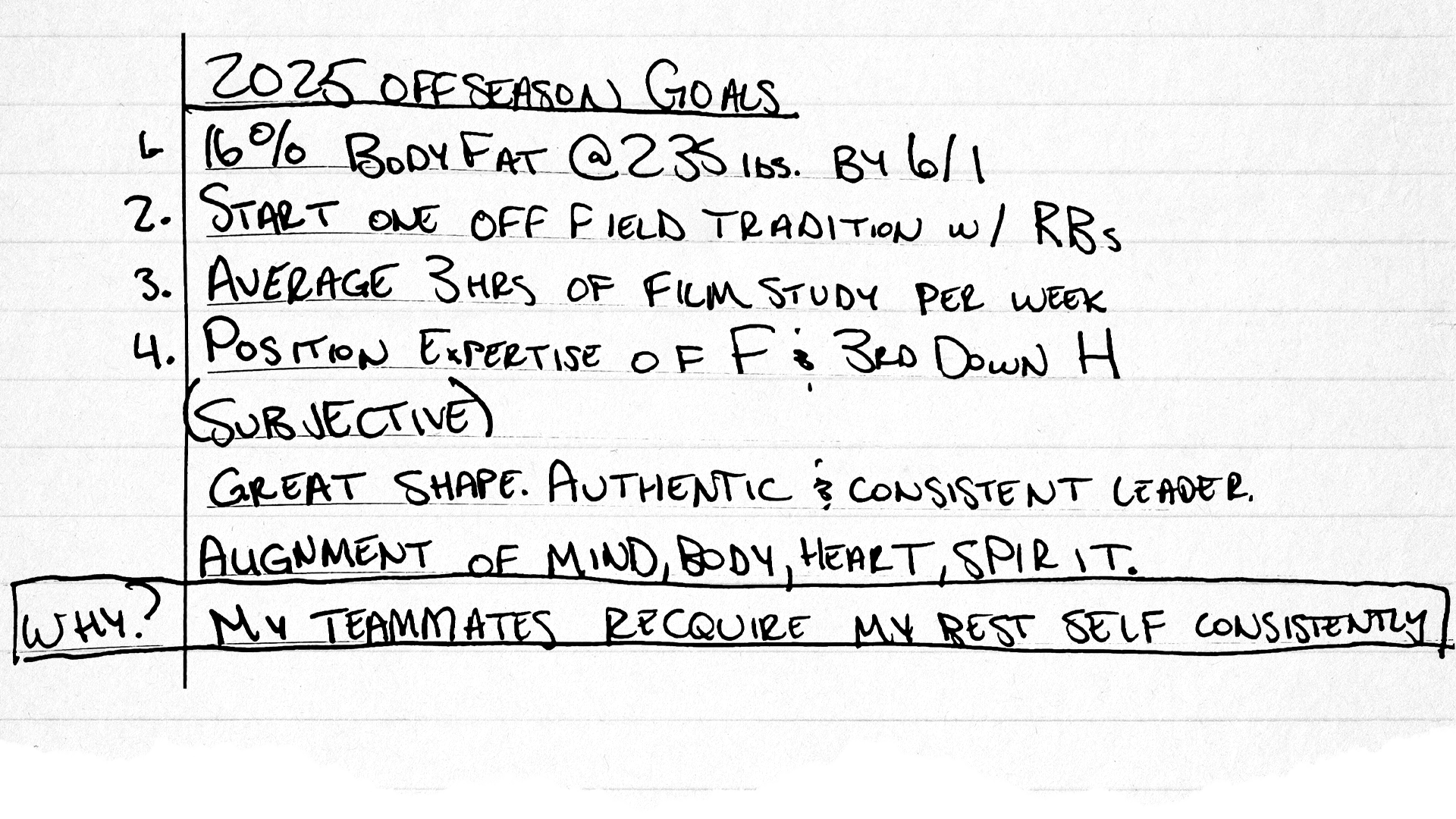

You’ll notice Ingold split this next section into two categories: objective goals (body fat) and subjective goals (authentic leader).

Let’s start with the subjective goals.

Ingold: “I really wanted to nail down big-picture goals and then break them down. So when I say subjective: I wanted to be an authentic leader. I wanted to be in great physical condition. I literally pictured the perfect offseason: what I look like, what I feel like, how I’m doing things. And from there, I broke out four controllable and very objective goals.”

That gets us to his more measurable goals.

Ingold: “I need to be at this body fat percentage to prove to myself that my body was in great shape. I need to intentionally plan new off-the-field traditions with the running backs because that’s authentic to the relationships you’re trying to build, the leader you’re trying to be.* Through those measurable, controllable goals, I felt like I reverse-engineered the vision of me being at my best at the end of the offseason.”

*The off-field tradition? Steak dinner bets.

Mostly, I was curious how he saw objective and subjective goals working together.

Ingold: “Subjective goals allow for you to be creative. It allows you to paint a picture: who you want to be and what you want to do. The objective is about finding those measurable, literal ways to prove to yourself that you’re on the right track and doing the right things to create the outcome you want.”

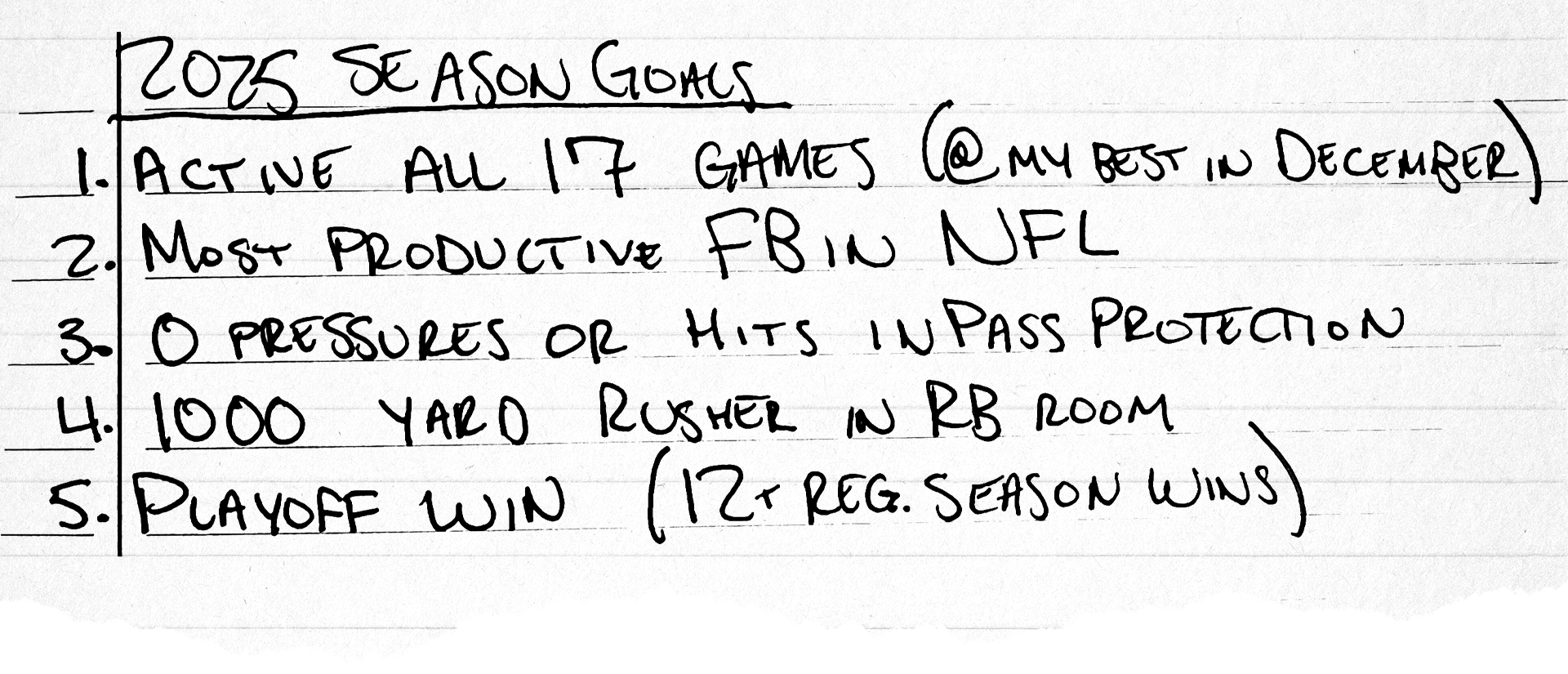

Immediately, you’ll notice that many of these goals feel out of Ingold’s individual control.

Ingold: “They’re measurable for sure. They’re objective for sure. But they’re a little bit out of my control so that competitiveness drives me to dig deep and fight to push toward the limit. I probably only got half of those goals, but I also didn’t attach failure of a goal to my identity. If you are dominating your day to day throughout the whole process, you’ll get a whole heck of a lot closer to those goals. Or you’re closer to the best version of yourself because you’re chasing it.”

Ingold acknowledged these are the biggest-picture goals, the kind they put in your Wikipedia bio. There is a reason for that.

Ingold: “It’s important to create a North Star to determine why you’re trying so hard and what you’re going after for sustained success. And I did prioritize this list. We’re in this game to win Super Bowls, so that’s No. 1 on my list. And then all the way down to individual accolades at the bottom. Do those define your career or legacy? Probably not. But they do indicate that you’re doing stuff the right way for an extremely long period of time.”

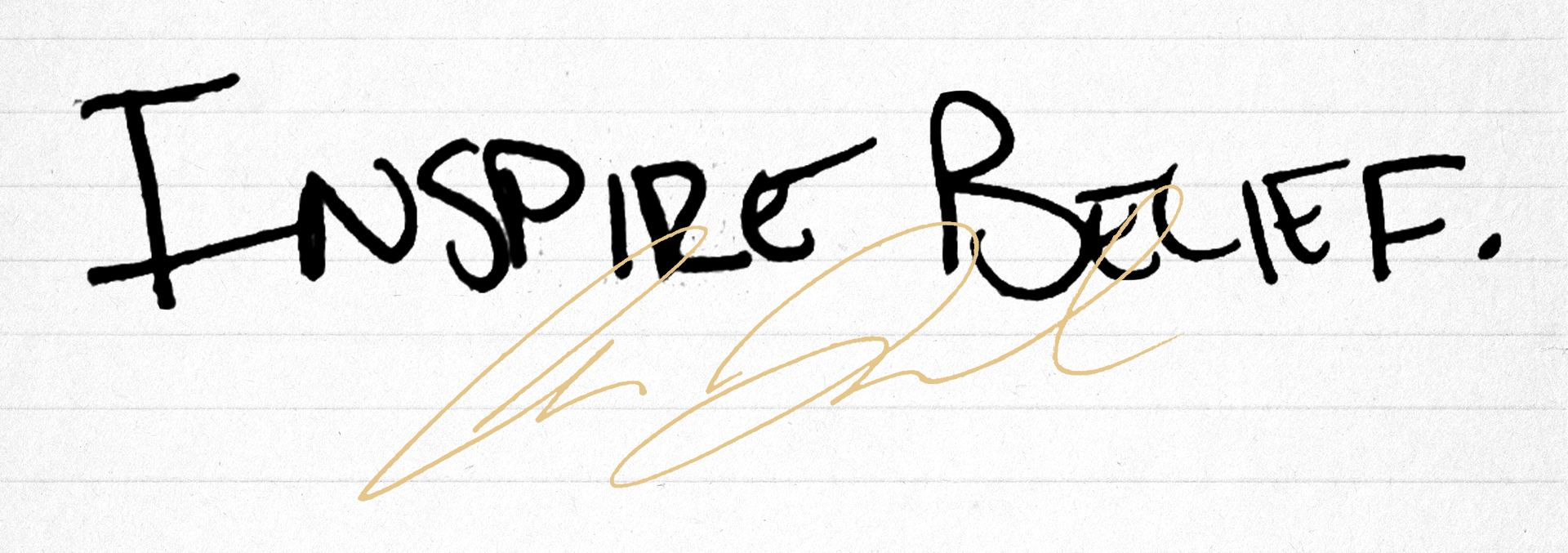

Ingold said “inspire belief” was his mission statement, his “why.”

Ingold: “I want to inspire others to believe in the best version of themselves. I also want to inspire myself to believe in the best version of myself, too. That’s one of my huge struggles. I felt like if I attached my why and purpose statement at the bottom there, it tied the career goals to the season goals and the season goals to the offseason goals. That was also the final reminder for myself when I reflect on these goals.”

The idea for the signature, he said, was something he picked up from Kobe Bryant.

Ingold: “So when things are hard, when you’re 1-6 and pissed off in Atlanta, you don’t waver. You don’t flinch. That signature created this desired heart with me to stay committed to that process.”

Ingold kept his goal sheet in his playbook. Once a month, he reviewed it and journaled to see if he was on track. Speaking of …

I’m (still) eating like an NFL player

For those who are new here: In the first edition of the newsletter last week, I said I was going to try eating healthily, like former NFL player Lorenzo Alexander.

Five days in, I’m here to report back: So far, so good. I even took a picture of what my wife and I are eating for breakfast as proof.

In next week’s newsletter, I’m going to dive more into how elite athletes set and stick to goals (that’s a tease!), but one thing I can say for sure: Making your goal public in a newsletter is one good way to hold yourself accountable and force you to stick with it, even when a bag of chips is trying to turn me into Gollum from “The Lord of the Rings.”

In all seriousness, I’m not even totally sure if I feel better on this diet. Maybe it’s just too soon to tell. But I do feel more … disciplined. I’ve never considered myself a disciplined person. But I’m reminded of something Richard Jefferson, the longtime NBA player, said recently when I mentioned that to him:

“You might struggle with the discipline to go to the gym; I struggle with the discipline to return a freaking email or text. We all struggle with different disciplines.”

If you’ve stuck with Alexander’s diet, how are you feeling? Email me: peak@theathletic.com. And if you want to try it, check out the parameters here.

Peak Nuggets

Bite-sized ideas from around sports:

🏈 Indiana football coach Curt Cignetti is never happy. Ahead of the college football national championship Monday, a former player details why that’s a good thing.

📕 Elise explains why small one moment from a team captain was a textbook display of leadership.

🎤 Laura Okmin was an NFL sideline reporter. Now she helps coaches find their blind spots. Cool story from Rustin Dodd here.

🎥 Walk and talk: Elise shares weekly insights while walking around New York City. This week’s topic? A former NFL player’s trick for sticking with a New Year’s resolution.

Click the GIF below to hear it.

🎶Peak Playlist

Every week, I ask someone for a song that motivates them. This week, it was Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Derrick Johnson, who recently wrote about the three lessons he learned when he was benched in the NFL.

His song: “Gonna Be A Lovely Day” by Kirk Franklin

His reason: “Gave me a sense of hope regardless of what was about to happen.”

You asked…and Michael Phelps answered

Sean G. wanted to know about Michael Phelps’ mindset and mentality. Wrote Sean: “I’d like a peek into his mind in order to help me emulate that and gain a mental edge.”

So we reached out to Phelps. Here’s what he said:

💬 “It all comes back to preparation. If you’re not prepared, you’re going to be extra nervous, you’re going to think maybe you’re not ready for this or that, and then your mind naturally plays these tricks with your head. That’s why I always loved competition and meets so much. I got a chance to see where I was in my training and see what I needed to fix so I didn’t have that happen again.

“My losses always stayed with me. And when I was in practice every day, those were the things that motivated me.”

(Check out Elise’s story where she journaled like Phelps for a week.)

🗣️ Got a question about the mental side of sports that you want answered by a player, coach or expert? Email me at peak@theathletic.com. Every week, I’ll pick a question and get an answer.

📫 Love Peak? Check out The Athletic’s other newsletters.