After wielding the power of nerdy numbers to identify the most predictive metrics for quarterback prospects and edge rusher prospects in the first round of the NFL draft, it’s time to do the same for wide receivers.

I compiled the college and NFL production of the 32 wide receivers drafted in the first round from 2018 to 2024, hoping to identify college metrics that featured a noticeable correlation with NFL success.

Here are the results.

Methodology

Why 2018-24?

First off: Why did we limit the sample to 2018-24? For our QB and EDGE studies, we went all the way back to 2015.

The main reason is that NFL offenses have changed so much in the past decade-plus that it felt like apples-to-oranges to compare first-round wideouts from 2015 to those we are about to see drafted in 2026.

Back in the mid-2010s, big-bodied X receivers were still all the rage; think Mike Williams, Laquon Treadwell, and Kevin White. Nowadays, those types of receivers have been relegated to complementary roles, while smaller, quicker receivers have taken over the league, like Ja’Marr Chase and Jefferson.

Starting around 2018, when D.J. Moore and Calvin Ridley went in the first round, we have seen a drastic shift in the types of receivers targeted in the first round. So, it made sense to place our cut-off there. Not to mention, there are enough receivers drafted in the first round each year that we still get a sizable sample to analyze, even from just a seven-year stretch.

What constitutes NFL success?

We’re trying to find out which college metrics are the strongest indicators of how “good” a player will be in the NFL. To do that, we need a number that quantifies a player’s NFL success.

For quarterbacks, we combined several efficiency metrics into a single rating. For edge rushers, we relied on Pro Football Focus grades, as they felt like the best encapsulation of an edge rusher’s all-around impact.

For receivers, I think the best bet is to simply rely on their box-score production. It is far from perfect, but a better tool isn’t readily available to evaluate the full extent of a receiver’s impact (PFF grades for wide receivers are not very good at accounting for quarterback play and other contextual factors). Ultimately, a receiver’s box-score production is the basis of his pay and reputation, anyway.

To narrow it down to one number, the best method is to use a fantasy-scoring system. We could go with the traditional system (yards and touchdowns) or the PPR (points per reception) system.

I settled on a middle ground. I think we need more than just yards and touchdowns, and I also think it is silly to credit receptions without context (why is a zero-yard reception worthy of credit?), so I went with a points-per-first-down system.

Here is how the scoring works:

0.1 points per receiving yard

6.0 points per receiving touchdown

1.0 point per receiving first down

Using this system, each player’s career fantasy points per game (regular season) served as the metric for quantifying NFL success.

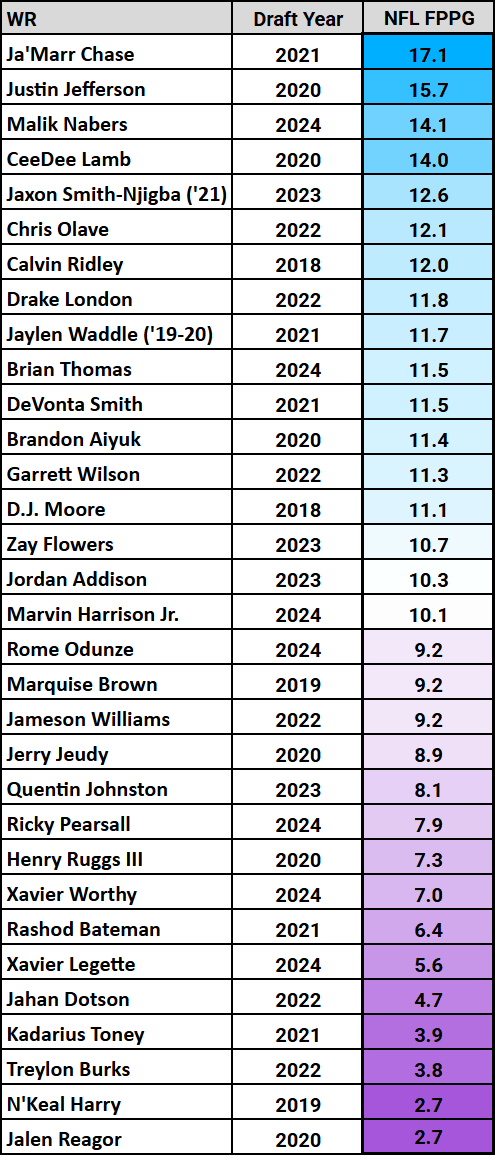

Here is the player list.

The group average for fantasy points per game is 9.5.

I then analyzed how 20 different metrics from the 32 players’ final college seasons correlated with fantasy points per game in the NFL.

Most predictive college metrics for first-round WR prospects

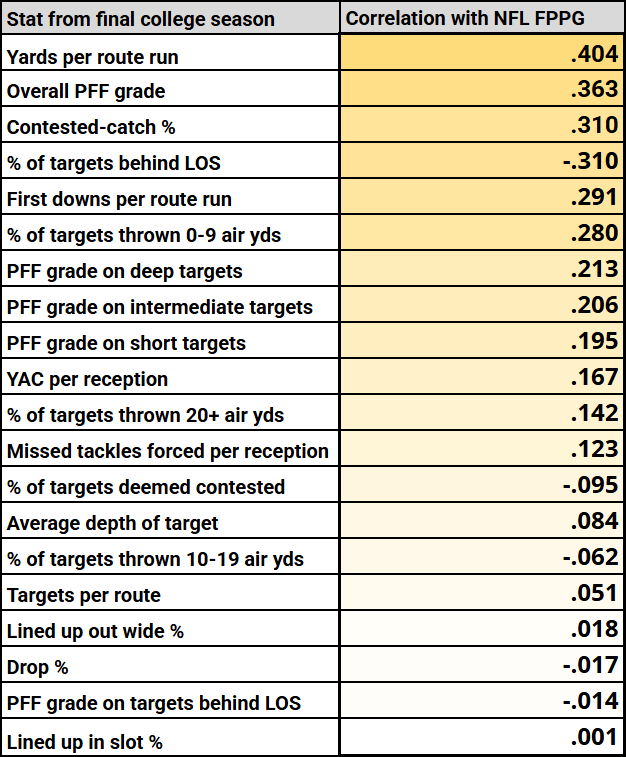

Seen below is the correlation coefficient between each of the 20 metrics and NFL fantasy points per game. For perspective, a correlation coefficient of 0.000 represents zero correlation; the closer it is to 1.000 (perfect positive correlation) or -1.000 (perfect negative correlation), the stronger the correlation.

Many of these metrics meant absolutely nothing, but a few stood out as carrying more weight than the rest.

In particular, there were four metrics that carried a correlation coefficient of greater than .300/-.300, which is sometimes considered to be the threshold for a “moderate correlation”:

Yards per route run (.404)

Overall PFF grade (.363)

Contested-catch rate (.310)

Percentage of targets behind line of scrimmage (-.310)

Why did these metrics stand out as the most important?

Yards per route run (.404)

Simply put, this metric divides a player’s total receiving yards by the number of snaps in which their team passed the ball (routes run). It is a simple metric for gauging a receiver’s overall dominance, as it evaluates their ability to produce yardage on a per-opportunity basis.

One of the great benefits of yards per route run is that it allows us to evaluate all receivers on a similar plane. Some receivers play in offenses that pass more frequently than others. This can skew the final numbers that show up in a box score.

For instance, it would not be fair to compare the numbers of a receiver in the Cardinals’ offense (league-high 629 pass attempts in 2025) to one in the Ravens’ offense (league-low 422 passes) without accounting for the difference in opportunities. This is where yards per route run comes in. By accounting for a player’s volume of opportunities, we remove a variable that is outside the player’s control.

This likely explains why it is such a solid metric for predicting NFL success.

If we only look at total receiving yards, touchdowns, or receptions, we are not going to learn much, as college prospects hail from all different types of offenses. Some prospects even got to play multiple more games on their schedule than others, which is another way that box-score stats can be skewed.

Yards per route run is an even-plane metric that answers a simple question: How many yards does this player produce every time his team passes the ball?

While the correlation is nowhere close to perfect, it seems clear that first-round prospects who produce a high rate of yards per route run in college tend to perform better in the NFL than those who produced a relatively low rate of yards per route run.

There were nine players in the group who averaged at least 3.50 yards per route run in their final college season, and seven of them are averaging at least 11 fantasy points per game in the NFL:

DeVonta Smith (4.39): 11.5 FPPG

Jaxon Smith-Njigba (4.01): 12.6

CeeDee Lamb (3.99): 14.0

Malik Nabers (3.64): 14.1

Treylon Burks (3.57): 3.8

Jaylen Waddle (3.56): 11.7

Marquise Brown (3.56): 9.2

Ja’Marr Chase (3.52): 17.1

Drake London (3.52): 11.8

That’s a pretty darn good hit rate.

Overall PFF grade (.363)

I think wide receiver may be the weakest position for the PFF grading system, as it appears to do little to account for the receiver’s quarterback play and other surrounding variables. It also seems to focus mainly on the plays where the receiver was targeted, which does not make much sense.

What the PFF grade does a good job of for receivers is estimating the quality of a player’s receptions. Receivers who stockpile production on schemed-open receptions are not going to score well in this system. The receivers who score high in the PFF grading system are those who generate their production through their individual effort, whether it’s a fantastic route, a contested catch, or electric moves after the catch.

This explains why it has value in predicting the NFL success of college prospects. The better the PFF grade, the likelier it is that the prospect was thoroughly dominating his opponents by way of his own skill, rather than accumulating production on the basis of the system he played in.

The six players who hit a 90.0 PFF grade in their final college season have been surefire stars in the NFL:

DeVonta Smith (94.9): 11.5 FPPG

Malik Nabers (92.9): 14.1

Jaxon Smith-Njigba (91.7): 12.6

Drake London (91.3): 11.8

Ja’Marr Chase (91.1): 17.1

CeeDee Lamb (90.0): 14.0

Contested-catch rate (.310)

This one goes hand-in-hand with the PFF grade. If a player is catching a higher percentage of his contested targets in college, it suggests that he displayed physical dominance over his college opponents, signaling that he is cut out to handle the jump in competition to the NFL.

Meanwhile, if a player could not catch contested passes at a high rate in college, it’s a daunting sign, as the cornerbacks in the NFL will only be longer and stronger.

To be clear, none of these metrics has a strong enough correlation to indicate that a prospect is a guaranteed hit if he thrives, nor a guaranteed whiff if he struggles. Simply put, they indicate that there is certainly a higher chance of the prospect hitting if he thrives, and vice versa if he struggles.

Behind-the-LOS target rate (-.310)

This is the most fascinating inclusion in the top four. It is the only metric that has to do with a player’s role and usage rather than his individual performance.

Players have tended to perform better in the NFL the less they were targeted behind the line of scrimmage in college. Why would that be the case?

It could be a coincidence, but I think there is real value to it. Here’s my hypothesis: The less often a player catches passes behind the line of scrimmage, the more legitimate his production is. It indicates that he emerged as a college star by way of receptions that he had to earn through his route-running and hands, rather than profiting from schemed-up screens that required no route-running or pass-catching skills.

A high behind-the-LOS target rate is a warning sign of a high bust chance. There are 19 players in the group who were targeted behind the line of scrimmage on over 18% of their targets, and 12 of them (63%) are averaging under 9.5 fantasy points per game in the NFL (the group average).

Of the 13 players who were targeted behind the line of scrimmage on less than 18% of their targets, only three of them (23%) have produced less than 9.5 fantasy points per game in the NFL.

Big 4 Score

In our edge rusher analysis, we combined the top four most predictive metrics into a single “Big 4 Score”, which, in itself, was even more predictive than any of the four metrics on their own.

We’re going to do the same for wide receivers.

I rated each of the 32 prospects on a 0-100 scale for their performance in each of yards per route run, overall PFF grade, contested-catch rate, and behind-the-LOS target rate. The worst player in each category received a zero, the best received a 100, and the rest of the group was rated relative to the best player.

The four ratings were averaged together to create the Big 4 Score.

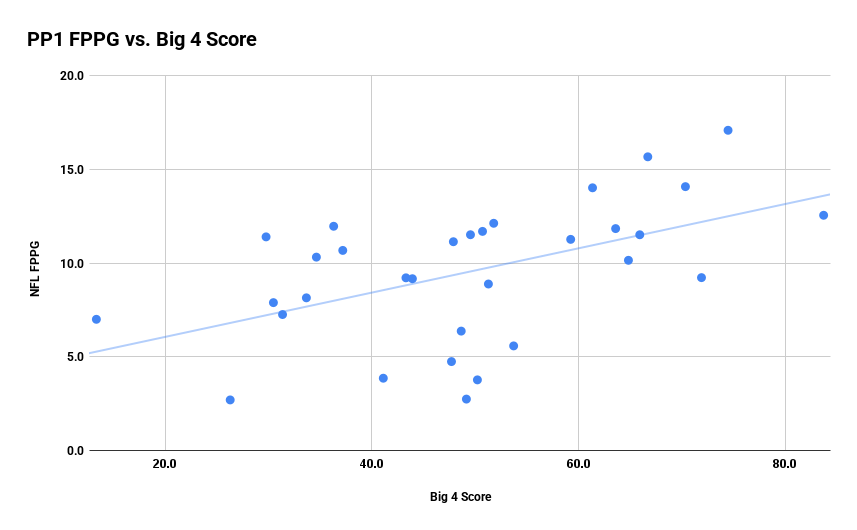

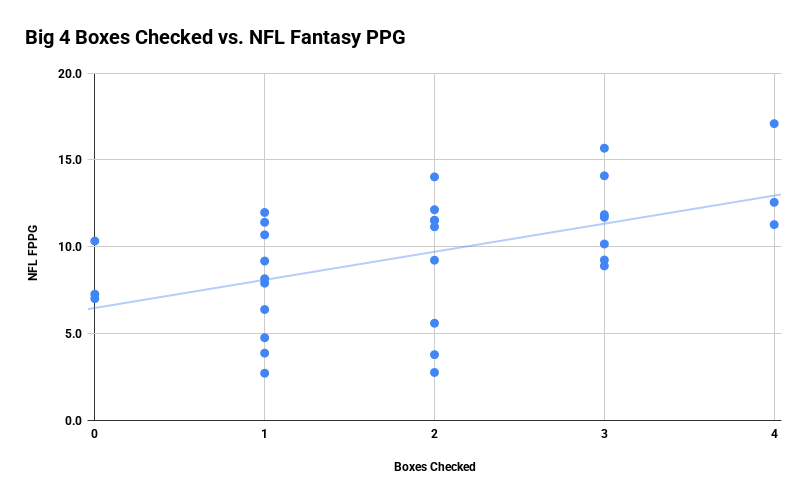

There was a whopping .517 correlation coefficient between Big 4 Score and NFL fantasy points per game.

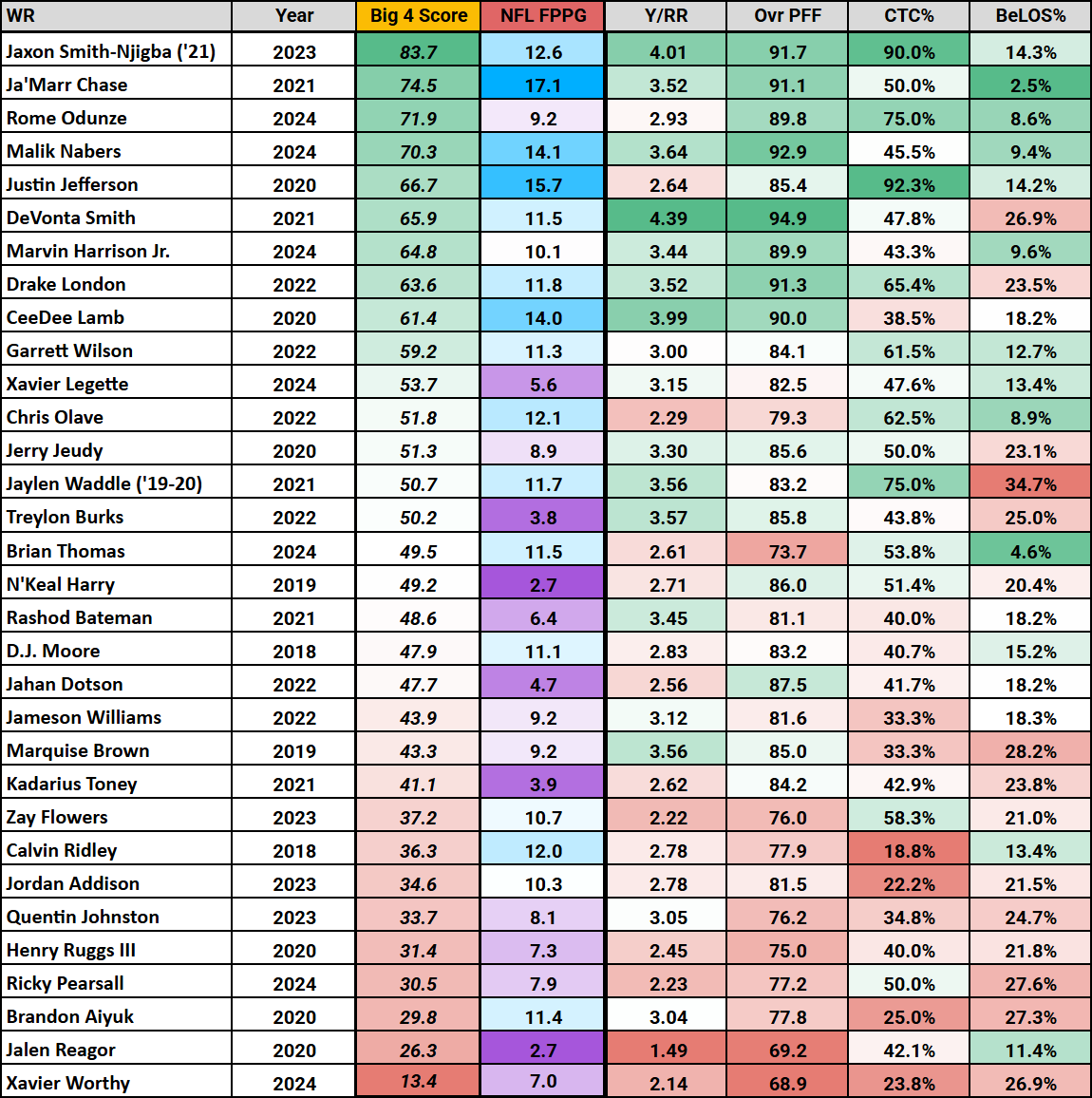

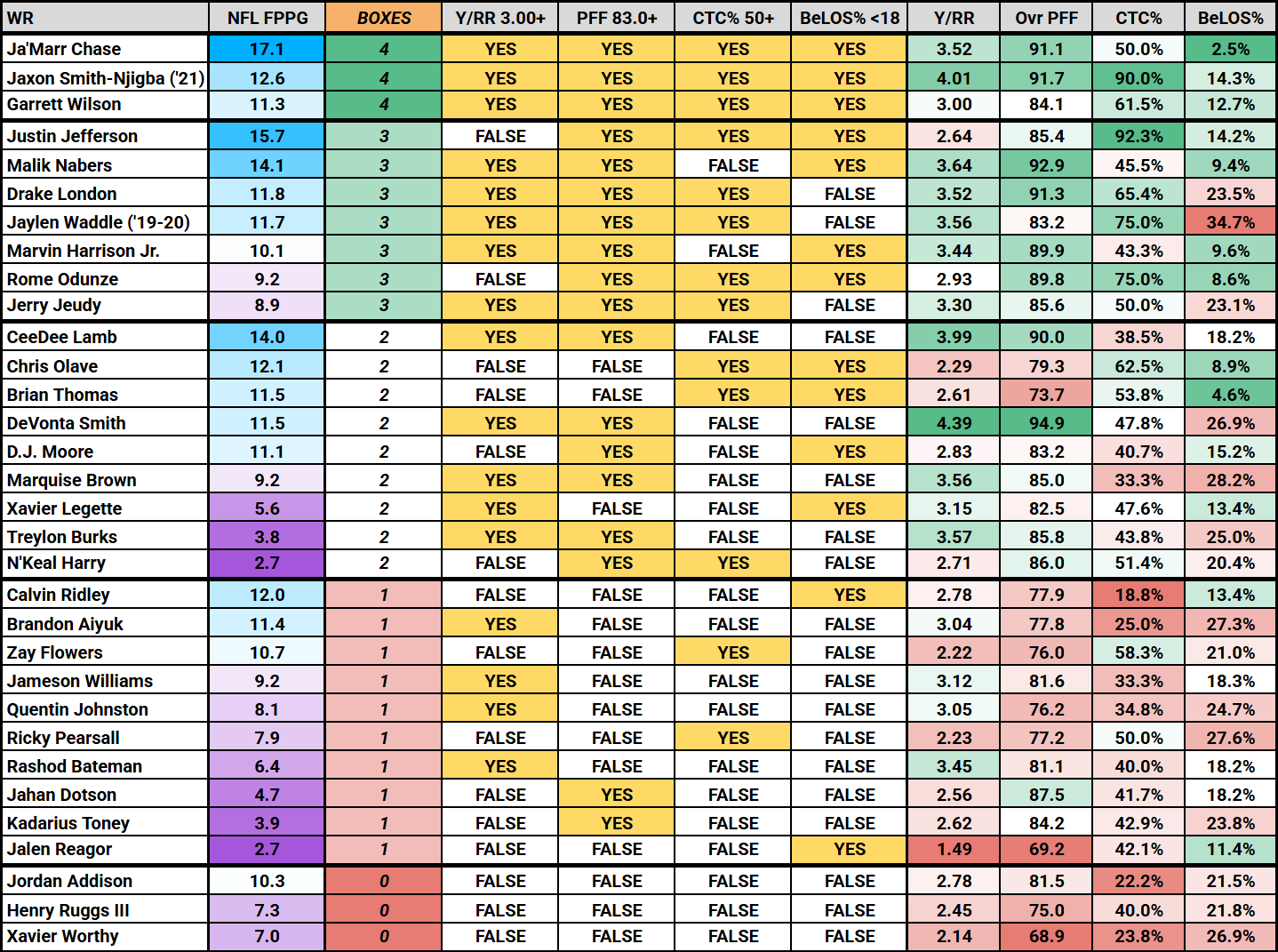

Here is the list of 32 first-round wide receivers with their Big 4 Score shown alongside their NFL fantasy points per game, showcasing the correlation between the two. On the right side of the table are the four final-college-season metrics that are combined to generate the Big 4 Score: yards per route run, overall PFF grade, contested-catch rate, and behind-the-LOS target rate.

As you can see, the top-rated prospects in Big 4 Score have mostly become stars in the NFL. Of the 10 players with a Big 4 Score above 55.0, nine are averaging at least 10 fantasy points per game in the NFL, and the floor is Rome Odunze at 9.2, who is still young and could become more productive throughout his career.

Beyond the top 10, there is a steep drop-off between Garrett Wilson and Xavier Legette, and that’s where the NFL production begins tailing off. It’s not a be-all, end-all to find yourself in this region, as there are productive players to be found outside the top 10, but the bust rate is much higher.

What are the ideal thresholds?

Another way to look at this is to understand what the ideal thresholds are in each category.

Here are the group averages in each of the four metrics:

Yards per route run: 3.02

Overall PFF grade: 83.1

Contested-catch rate: 48.1%

Behind-the-LOS target rate: 18.4%

To simplify things, let’s round these numbers out to establish some clear benchmarks that we should look for in prospects:

Yards per route run: 3.00+

Overall PFF grade: 83.0+

Contested-catch rate: 50%+

Behind-the-LOS target rate: <18%

Prospects tend to perform better the more of these boxes they checked:

Prospects to check 3-4 boxes (10): 12.4 NFL FPPG

Prospects to check 2 boxes (9): 9.1 NFL FPPG

Prospects to check 0-1 boxes (13): 7.8 NFL FPPG

There is a .510 correlation coefficient between the numbers of these boxes checked and NFL fantasy points per game.

Take a look at the player list.

What did we learn?

Coming in, my hypothesis was that I would not find any metrics that could help us predict the success of wide receiver prospects. I thought the conclusion of this article would be that numbers cannot tell us anything meaningful about wide receiver prospects.

More than just about any other position, receivers depend on factors outside of their control to be productive. For that reason, I did not think we could learn much about them from the numbers. They seemed like a position that could only be fully understood through a thorough film review.

As it turns out, wide receivers are similar to edge rushers in that college production actually can be a useful predictor of NFL success.

Edge rushers’ production featured a stronger correlation than receivers, which makes sense, as edge rushers are not affected by as many variables as receivers. Still, receivers were not too far off in the correlation between college success and NFL success. We discovered some real signals that are worth putting stock in.

Yards per route run and overall PFF grade are metrics that encapsulate a receiver’s all-around dominance. They carried far more predictive weight than more specific measures of receiver play, like drops, YAC, missed tackles forced, or production at any specific level of the field.

It goes to show that, like edge rushers, if a first-round prospect had the skill set to dominate in college, there is a good shot he will keep it up in the NFL. The opposite is true; if they could not dominate weaker opponents in college, there is a good shot they won’t suddenly figure out how to do it against stronger opponents in the NFL.

You just have to know what metrics to look at. A quick glance at yards and touchdowns won’t tell you much. Every prospect looks flashy in the box score. If they didn’t, they would not go to the NFL. But when we use metrics like yards per route run and PFF grade (and specifically compare prospects to other first-round prospects, rather than the rest of college football), every prospect is evaluated on the same plane, helping us identify who the real standouts are.

As for contested-catch rate, it speaks to the value of identifying receivers who can make the true difference-making plays that defy the scheme or the quarterback.

Any NFL receiver can catch a wide-open ball that was schemed up for him or a perfectly thrown pass from a great quarterback. What separates the star receivers from the replaceable ones is the ability to make logic-defying grabs in situations where the play-call and quarterback could not create an uncontested catch opportunity. These are the plays where wide receivers make the biggest impact on a game.

Dominating on contested catches in college seems to be a good sign that a player can do it in the NFL. The competition will be stiffer, so the expectation is that every college prospect will catch a lower rate of contested passes at the pro level. So, they had better come to the league with a high contested catch rate from college. If they were below 50% against scrubs, they don’t have a great outlook against the Sauce Gardners of the world.

Finally, behind-the-LOS target rate speaks to the importance of valuing prospects who did not come from a gimmicky college scheme that force-fed them easy receptions. The less of these targets that a prospect received, the more legitimate their overall production is, and the more ready they are for a professional offense.

Screen passes are arguably the least valuable thing on a college receiver’s tape. Going back to our original list that displayed the correlation coefficients for all 20 metrics, we can see that prospects’ PFF grades on behind-the-LOS targets had essentially zero correlation with NFL success, whereas their PFF grades on short, intermediate, and deep targets each had slight correlation.

It shows that what a prospect does with his screen plays means nothing as we project him to an NFL offense. Those are plays where the prospect can simply out-athlete the less talented defenders across from him; there is no route-running precision or pass-catching difficulty. Therefore, it makes sense that receivers who get the most of these targets tend to be less productive at the pro level.

Going forward, NFL teams should learn to prioritize first-round wide receiver prospects with dominant overall production (relative to other first-round prospects in key efficiency metrics like yards per route run and overall PFF grade), high efficiency in contested-catch situations, and low frequencies of screen passes.

Stay tuned for a follow-up article where we evaluate how the 2026 wide receiver class fares in these critical metrics.