After identifying the quarterbacks and edge rushers from the 2026 NFL draft class with the best (and worst) odds to succeed in the NFL, it’s time to turn our attention to the wide receivers.

Recap: Understanding the methodology behind correlative WR metrics

Before we dive into the 2026 prospects, let’s recap the methodology behind our analysis. The original article is worth revisiting if you want the fully fleshed-out explanation of everything we’ll discuss here, but today, I’ll keep it fairly concise so we can get to the 2026 class.

On Wednesday, we analyzed the pool of 32 first-round wide receivers chosen from 2018 to 2024, identifying the correlation between NFL success and 20 different college metrics (pulled from each player’s final season). Many of those metrics had little to no correlation with NFL success, but four stood out as doing the best job of predicting how productive a receiver will be in the NFL:

Yards per route run

Overall Pro Football Focus grade

Contested-catch rate

Percentage of targets thrown behind the line of scrimmage (lower = better)

By analyzing a prospect’s performance in these four metrics during his final college season, we were able to give ourselves a pretty good chance of predicting whether he would pan out in the NFL.

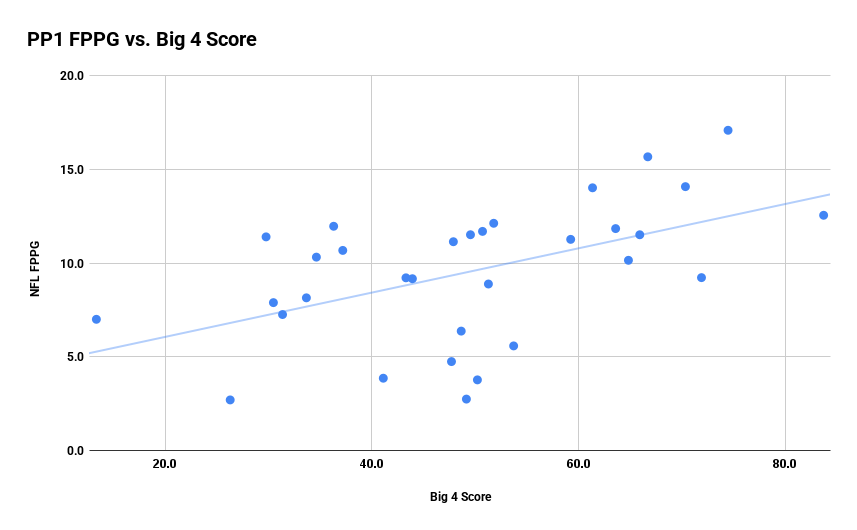

After combining a prospect’s performance across those four metrics into a 0-100 rating (dubbed “Big 4 Score”), there was a very noticeable correlation (r=0.517) with fantasy points per game in the NFL (using a 1-point-per-first-down system).

The better players performed in these four metrics during their final college season, the more productive they tended to be in the NFL.

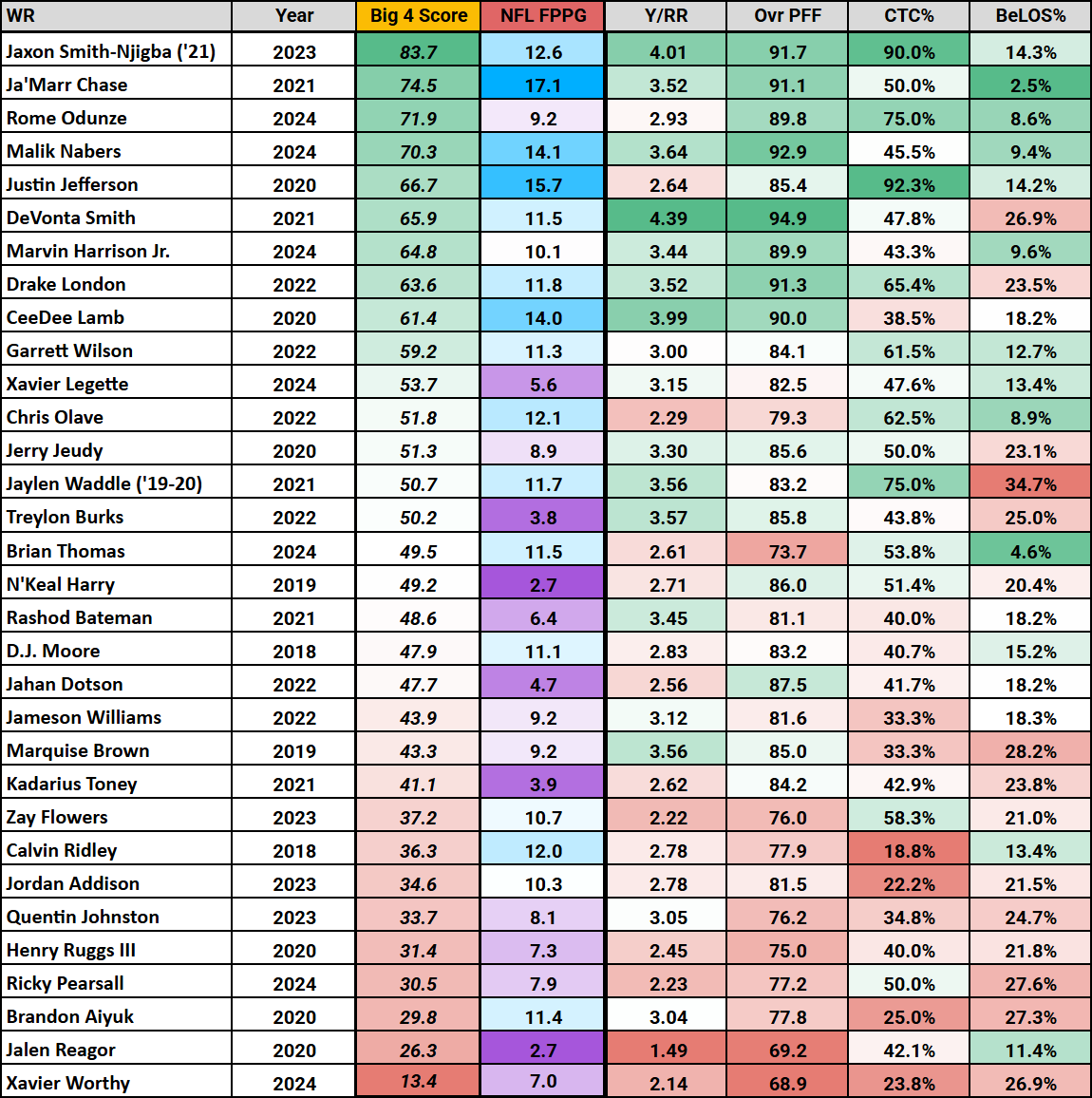

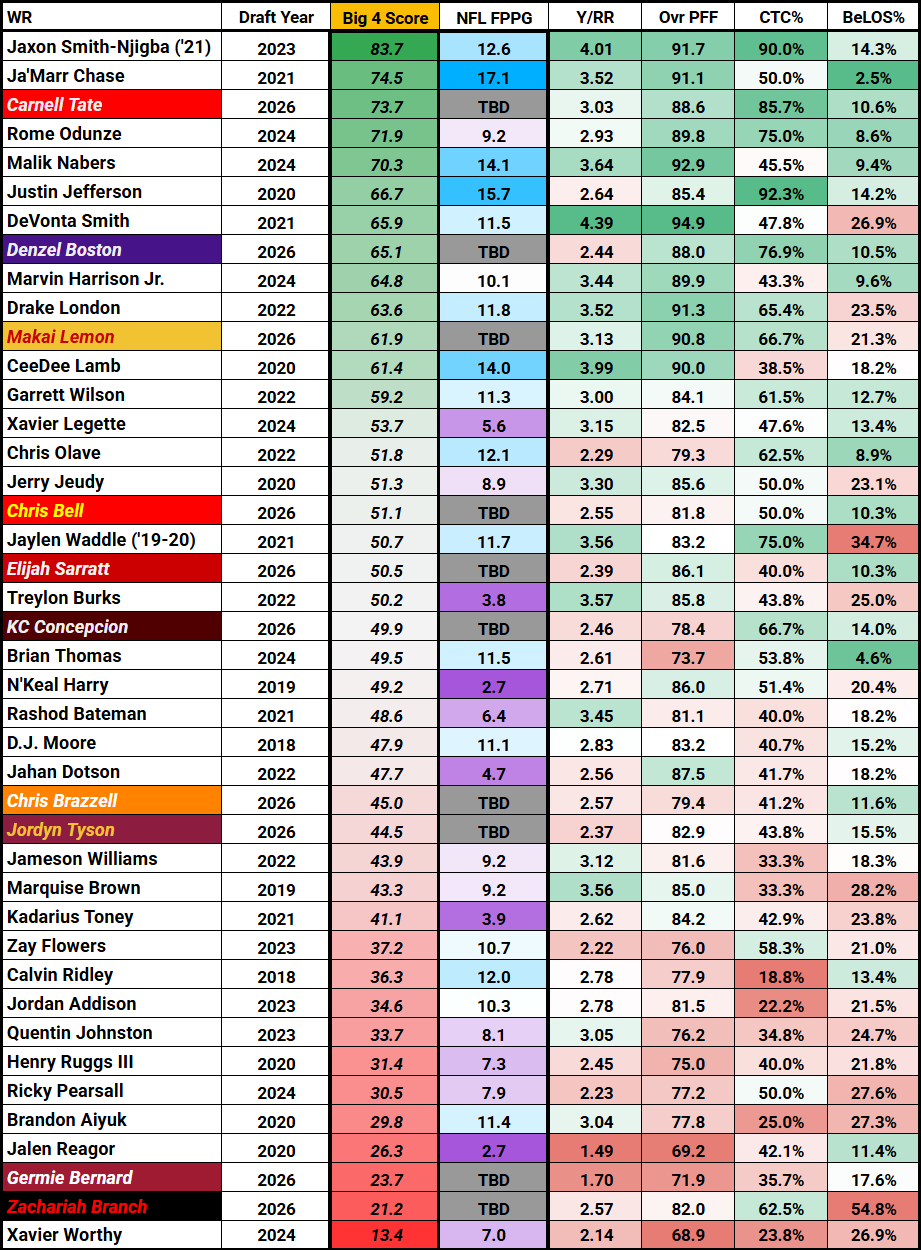

Here is the list of 32 wide receivers in the analysis, with their Big 4 Score shown alongside their current career average for fantasy points per game in the NFL. Shown on the right are the four metrics that factor into the Big 4 Score.

Another way of using the data is to establish ideal thresholds in each category.

Here are the group averages in each of the four metrics:

Yards per route run: 3.02

Overall PFF grade: 83.1

Contested-catch rate: 48.1%

Behind-the-LOS target rate: 18.4%

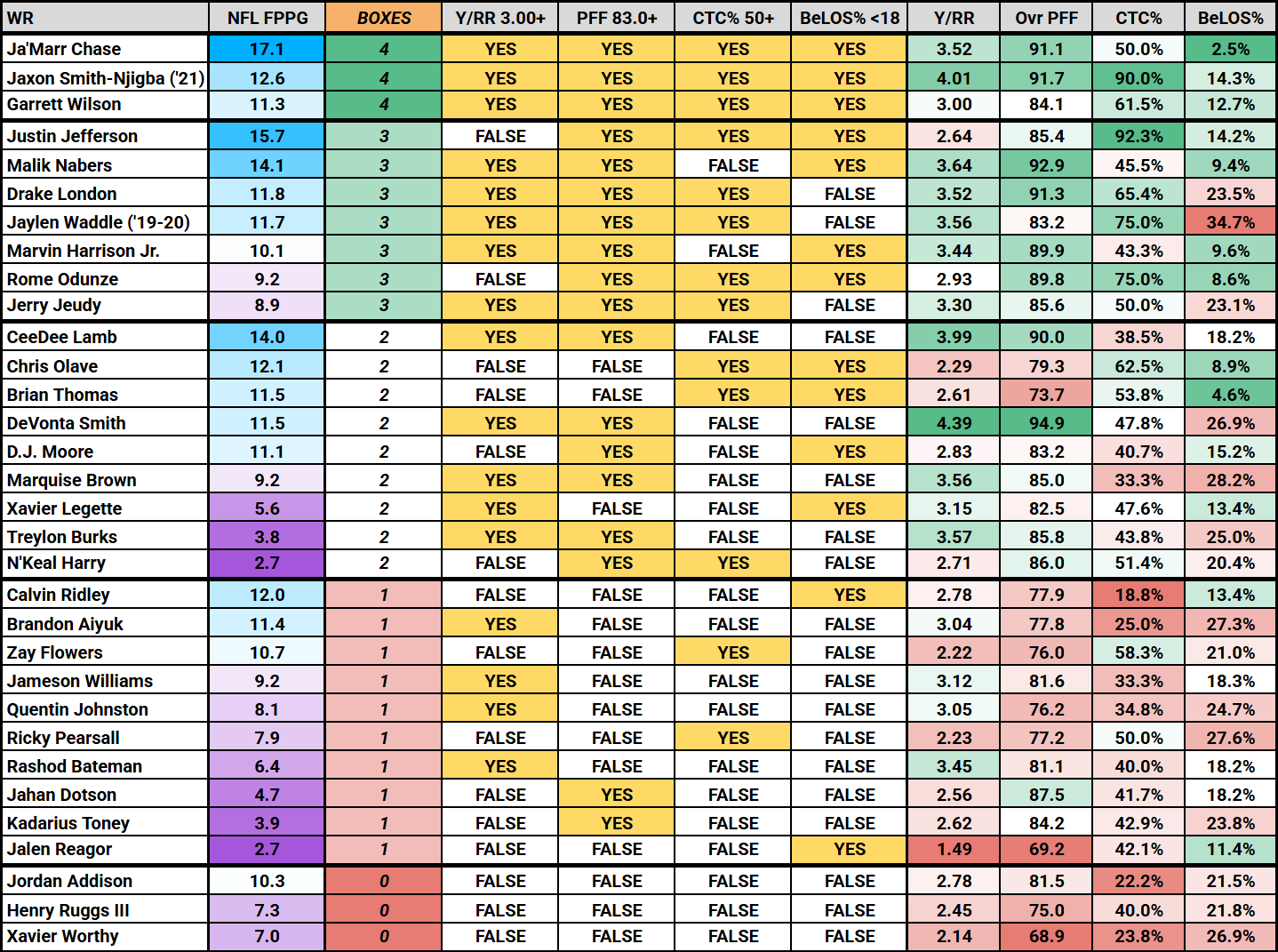

To give ourselves clear benchmarks to look for in prospects, I rounded these numbers out to the following thresholds:

Yards per route run: 3.00+

Overall PFF grade: 83.0+

Contested-catch rate: 50%+

Behind-the-LOS target rate: <18%

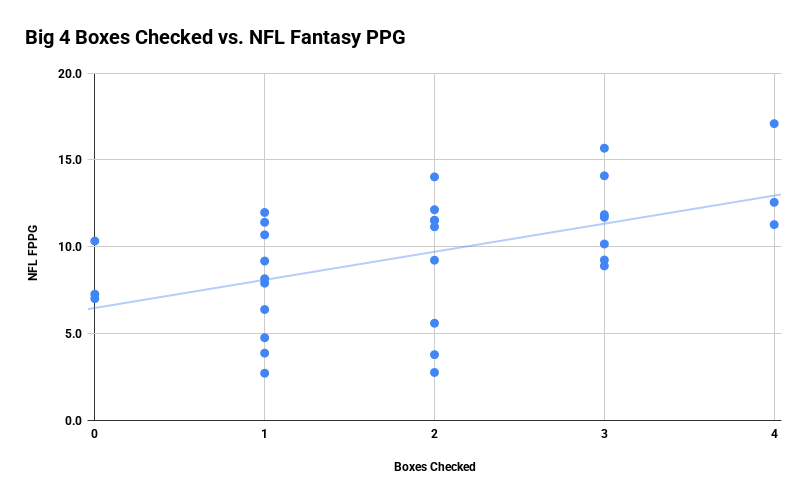

In the 32-player sample, prospects tended to perform better as they checked more of these four boxes:

Prospects to check 3-4 boxes (10): 12.4 NFL FPPG

Prospects to check 2 boxes (9): 9.1 NFL FPPG

Prospects to check 0-1 boxes (13): 7.8 NFL FPPG

The correlation coefficient between the number of boxes checked and NFL fantasy points per game was .510, which is quite noticeable.

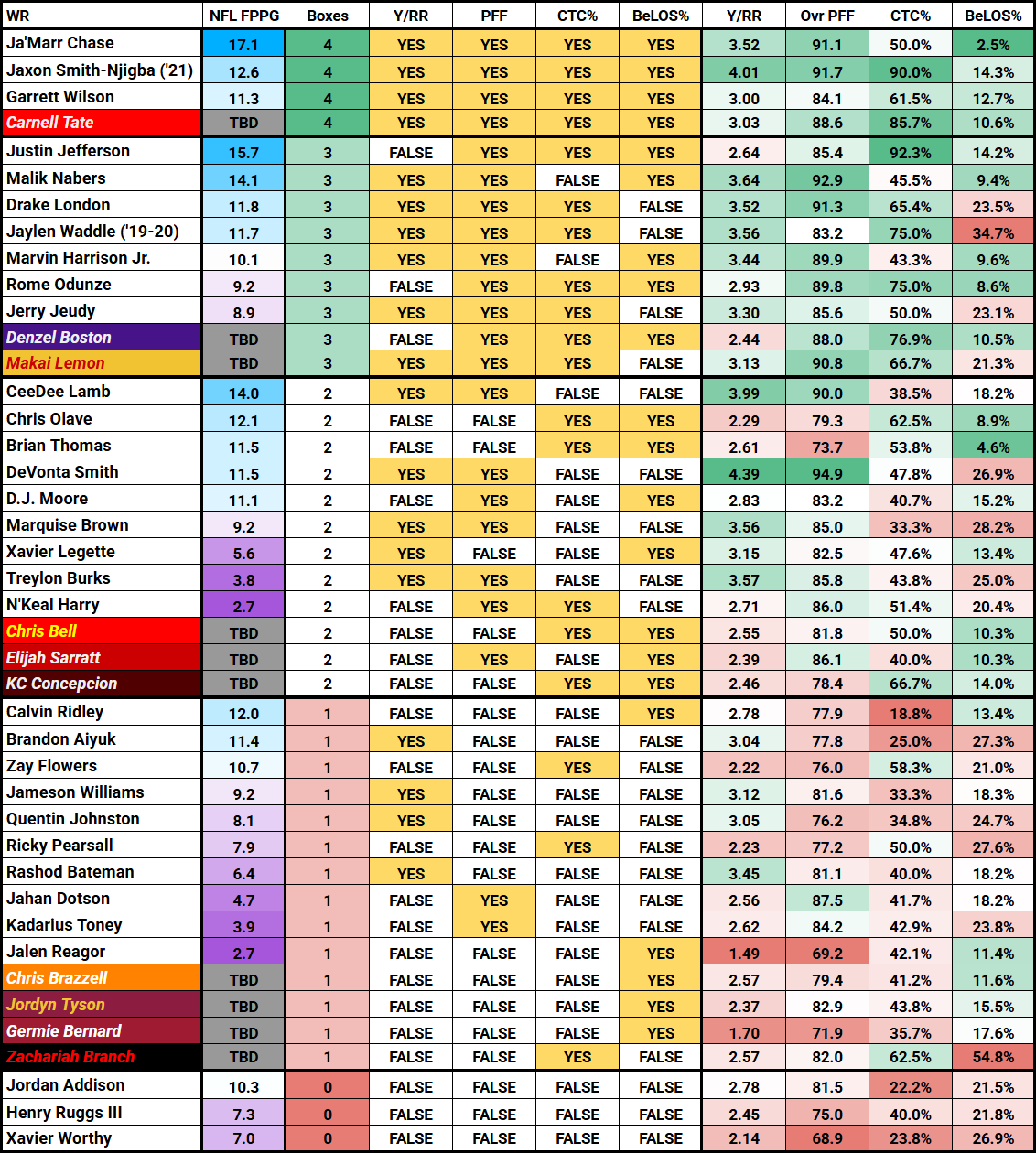

Take a look at the 32 players grouped into five tiers based on how many boxes they checked. Clearly, each tier of receivers offers a better hit rate than the next, with a particularly noticeable drop once you fall below two boxes.

Now that we have a feel for what we’re looking for in the 2026 wide receiver class, it’s time to dive into their numbers from the 2025 college football season.

2026 WR class in correlative metrics

We’re going to focus on the current top-10 wide receivers on the consensus big board at NFL Mock Draft Database:

(ranked #4 overall) Carnell Tate, Ohio State

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama

Each ranked top-52 on the consensus big board; it seems feasible to say that any of these players has a chance to be drafted in the first round, which makes it worthwhile to stack their profiles up against the first-round prospects of recent history.

Let’s see how they performed in each of the Big 4 categories.

Yards per route run

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC: 3.13

(#4) Carnell Tate, Ohio State: 3.03

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia: 2.57

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee: 2.57

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville: 2.55

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M: 2.46

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington: 2.44

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana: 2.39

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State: 2.37

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama: 1.70

This is not a good start for the 2026 class. Only two players, Lemon and Tate, hit the threshold we established earlier. Interestingly, Lemon has a slight advantage over Tate, the consensus WR1.

Yards per route run is a critical metric because it offers a contextualized evaluation of a receiver’s overall dominance. It accounts for the variable of how often a player’s team calls pass plays, which is out of their control. This is why total yards and yards per game are useless metrics for evaluating college prospects.

This metric allows us to evaluate every prospect on the same plane. Simply put, how much yardage do you generate per opportunity to do so?

Lemon and Tate stand out as the most dominant prospects in this regard. Nobody else is close to the median for a first-round prospect.

However, we still have three more metrics in which these prospects can strengthen their stock.

Overall PFF grade

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC: 90.8

(#4) Carnell Tate, Ohio State: 88.6

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington: 88.0

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana: 86.1

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State: 82.9

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia: 82.0

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville: 81.8

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee: 79.4

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M: 78.4

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama: 71.9

Once again, it’s Lemon edging out Tate for the top spot. Meanwhile, Boston and Sarratt join them in the group of players who cleared the ideal threshold.

Projected top-10 pick Jordyn Tyson falls a hair shy of the benchmark.

For wide receivers, what makes PFF’s grading system useful is that it rewards pass-catchers for making difficult plays. Contested catches, broken tackles, and beautiful routes will earn you big points in PFF’s system. Meanwhile, if you consistently profit from schemed-open routes, checkdowns, blown coverages, and other types of plays that do not require much difficulty, you aren’t going to earn many points from PFF.

Thus, it’s a nice way of evaluating the “quality” of a player’s production. Yards are yards, but there are so many different ways to get those yards. PFF’s grading system does a nice job of telling us whether a player “earned” his production.

It’s a great look for Lemon and Tate that they not only generated yards at an elite rate, but they also have the PFF grade to show they earned those yards through legitimately impressive plays. As for Boston and Sarratt, their strong grades show they stand out on film even if their per-snap production is not quite as dominant as someone like Lemon or Tate.

Meanwhile, things are not looking great for Tyson, the eighth-ranked overall prospect on the consensus big board. I’m not saying that people should take him off their draft boards because he fell 0.1 points shy of my arbitrary benchmark in a subjective grading system (or am I?), but whether he got that extra 0.1 or not, what matters is that his PFF grade is average and his yards-per-route-run is well below average. Those are red flags for a top-10 prospect, and it will be reflected in his Big 4 Score.

Contested-catch rate

(#4) Carnell Tate, Ohio State: 85.7%

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington: 76.9%

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC: 66.7%

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M: 66.7%

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia: 62.5%

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville: 50%

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State: 43.8%

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee: 41.2%

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana: 40%

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama: 35.7%

This is where Tate sets himself apart as the top dog. He caught an absurd 12 of 14 contested targets in 2025. In the 32-prospect data sample, the only players who exceeded a contested catch rate of 80% were Justin Jefferson (92.3%) and Jaxon Smith-Njigba (90%). Not too shabby.

Boston was not far off, grabbing 10 of 13 contested targets. Lemon also thrives here, although he loses pace with Tate. Concepcion and Branch stand out, while Bell hits the 50-50 benchmark.

Tyson falls short of the benchmark once again.

Contested catches are an important metric because they indicate a prospect’s physical dominance over his weak opponents in college. We can assume that a prospect will likely catch a lower rate of contested targets once he takes on vastly superior cornerbacks in the NFL, so if he wasn’t catching half of his contested targets against college corners, it is difficult to envision it happening against NFL corners.

It’s not impossible for a prospect to improve at contested catches in the NFL, but it sure feels safer to bet on the guy who was already snagging at least two-thirds of those 50-50 balls against college scrubs, which four of these players were able to do.

And, remember, we’re not analyzing the correlation between college contested-catch rate and NFL contested-catch rate; it’s between college contested-catch rate and overall production in the NFL.

The value here is that a high contested-catch rate in college indicates that the prospect has the makeup to succeed in the NFL as any type of receiver, whether the contested-catching itself translates or not. It seems to indicate that, through some combination of physical dominance and pure skill, the prospect has what it takes to translate his success to the pro level.

The players in the 32-man data sample who caught under 50% of their contested targets in college are averaging 8.5 fantasy points per game in the NFL, while those who caught at least 50% are averaging 11.0 fantasy points per game. That’s a pretty significant difference, equivalent in value to about 25 yards per game, or 2.5 first downs.

Behind-the-LOS target rate

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana: 10.3%

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville: 10.3%

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington: 10.5%

(#4) Carnell Tate, Ohio State: 10.6%

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee: 11.6%

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M: 14.0%

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State: 15.5%

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama: 17.6%

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC: 21.3%

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia: 54.8%

It’s interesting to ponder the appearance of behind-the-LOS target rate as one of the metrics that correlated the most with NFL success.

My hypothesis is that it essentially serves as a “validator” for a receiver’s production. The fewer of these targets a player saw, the more valid his overall production is, and vice versa.

Passes behind the line of scrimmage offer little to no value for NFL projection. They require zero route-running skill, zero contested-catch skill, and zero ability to read coverages. Receivers catch an easy, uncontested pass on a predetermined route, and then just use their superior athleticism to effortlessly shred through a defense full of players who will probably never appear in the NFL.

There is nothing we can learn from those plays, especially since our initial study showed that after-the-catch metrics, like YAC per reception and missed tackles forced per reception, offer little correlation with NFL success.

What we want to see from NFL receiver prospects is precise route-running, difficult catches, and intelligence. None of those skills can be evaluated on passes behind the line of scrimmage.

Therefore, it stands to reason that the players who saw fewer of these targets tend to be more successful in the NFL, whereas the players who saw more of them tend to be less successful. It’s not a hard rule, but it’s a trend.

We know that a receiver’s overall college production is a solid indicator of their NFL outlook, as shown by yards per route run and overall PFF grade. Behind-the-LOS target rate is an adjuster to those metrics, letting us know what percentage of the player’s overall production was earned through plays that actually matter in regard to their NFL projection.

The more of your overall production that came from screens, the less valid your overall production is as a means of predicting NFL success.

The good news for the 2026 class is that most of the top prospects did not profit from a high rate of behind-the-LOS targets. Eight of the 10 prospects had a behind-the-LOS target rate below our 18% benchmark. Tate’s 10.6% is extremely impressive for a guy who stood out as dominant across the other three metrics.

Lemon is the big loser here, with his 21.3% rate being double Tate’s 10.6%. Since Lemon slightly edged out Tate in yards per route run and overall PFF grade, it gives Tate the overall edge, as he achieved his production on a more valid diet of plays.

Big 4 Score

Let’s blend the four metrics into a 0-100 “Big 4 Score”, quantifying the player’s overall performance across the most predictive metrics for wide receivers. As a reminder, there was a 0.517 correlation coefficient between Big 4 Score and fantasy points per game in the NFL, which means this number is a pretty solid indicator.

(#4) Carnell Tate, Ohio State: 73.7

(#24) Denzel Boston, Washington: 65.1

(#16) Makai Lemon, USC: 61.9

(#41) Chris Bell, Louisville: 51.1

(#46) Elijah Sarratt, Indiana: 50.5

(#27) KC Concepcion, Texas A&M: 49.9

(#50) Chris Brazzell, Tennessee: 45.0

(#8) Jordyn Tyson, Arizona State: 44.5

(#52) Germie Bernard, Alabama: 23.7

(#45) Zachariah Branch, Georgia: 21.2

There you have it: Carnell Tate justifies his throne as the clear-cut No. 1 wide receiver in the 2026 class. His numbers indicate there is a great chance he will be an NFL star.

Making up the second tier are Boston and Lemon, who each posted excellent scores. Their chances of becoming NFL studs are quite good.

After that, we have a collection of receivers with relatively average ratings, which means we cannot say with a high degree of confidence whether they will either succeed or fail in the NFL. Included in the low end of this tier is Tyson.

At the bottom, Bernard and Branch seem firmly entrenched as second-round prospects at best.

Here is a look at the 10 prospects slotted alongside the 32 first-round wideouts chosen from 2018 to 2024:

Based on the company they share on this list, it would be surprising if Tate, Boston, and Lemon did not at least turn into solid starting receivers. Tate, in particular, has a high chance of becoming one of the league’s best receivers.

Here is a look at where the prospects fall based on the number of boxes they checked across the four thresholds.

Takeaways

Based on the numbers we looked at today, it’s fair to say that Carnell Tate deserves more chatter as a potential target for the New York Jets with the second overall pick. He profiles as a receiver with a strong chance of being a Jaxon Smith-Njigba, Justin Jefferson, or Ja’Marr Chase-type weapon.

Tate’s ceiling, and his odds of hitting that ceiling, are the stuff of a second overall pick. He performed even better in his position’s most correlative metrics than the two EDGE prospects receiving the most hype as potential Jets targets, Rueben Bain Jr. and Arvell Reese.

In fact, the No. 1 edge rusher in the 2026 class based on our analysis of correlative metrics was actually Texas Tech’s David Bailey, who posted a Big 4 Score of 71.8 across the top four most correlative metrics for edge rushers. Tate trumped Bailey with his 73.7 Big 4 Score in the wide receiver edition of this analysis.

Meanwhile, this analysis also yielded some interesting takeaways for the Jets’ outlook with the 16th overall pick.

USC’s Makai Lemon is commonly mocked to New York with that selection. Based on what we learned today about Lemon’s analytical profile, he appears more than worthy of that investment. Washington’s Denzel Boston, the consensus No. 24 overall prospect, also deserves consideration with the 16th pick.

However, beyond Tate, Lemon, and Boston, the top of this wide receiver class looks unreliable. Most of these prospects failed to dominate in college at the level you’d prefer to see from an early-round prospect. Tyson, in particular, was quite disappointing relative to his draft stock.

I look forward to checking back on this article in five years and seeing if my magical Google Sheets formulas turn out to be the stuff of legend or nothing more than gobbledygook.