On clear days the Chicago skyline is visible from Miller Beach in Gary, the skyscrapers rising above the horizon 25 miles across Lake Michigan. An enduring wall of gray clouds often obscures the view in winter, though, and on a recent February morning ice covered the dunes and the beach and extended well into the lake, small waves frozen atop each other near the shore.

Occasionally wet-suited surfers arrived in pursuit of waves that had yet to freeze, and others came to walk out onto the shelf ice. Don Plohg, who manages Gary’s parks, chases people off the ice just about every day. Until recently that was the extent of wintertime activity along the lakefront in Gary.

Now, though, it’s a place of aspiration for city leaders. A place to come and imagine possibilities.

To picture a grand if improbable vision: that of a new Chicago Bears stadium along the beach.

There is a plan, however rough or premature. However fantastical or far-fetched. There is a plan, with a Bears stadium somewhere near Miller Beach, with retail, restaurants and places of gathering: a year-round, multipurpose attraction near Indiana Dunes National Park, amid the hiking trails and kayaking spots and not far from city streets full of so much amassed heartbreak and neglect.

That it is a possibility at all, however remote and unlikely, has inspired an uncommon belief in this long-beleaguered city. Could it be Gary’s time after so many years of sorrow? Or is this nothing but a cruel dangling of possibility for a place so accustomed to loss and false hope? A group of city leaders, intent on changing Gary’s image, believe in their chances. The faith seems genuine.

Gary has gone all in on the Bears. But are the Bears serious about Gary?

“I think it’s going to be real nice on ‘Monday Night Football,’ with the aerial shots,” Carla Morgan, the city of Gary’s lead attorney, said of the lakefront site while she pulled into a parking lot just behind the dunes. She spoke as if she could already see the blimp’s view of a Bears stadium-to-be and the lake, with the lights of Chicago twinkling in the distance.

A site on Lake Michigan near Miller Beach, pictured on Jan. 19, 2026, is one of three sites proposed by Indiana for a future Bears stadium. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

A site near the Gary-Hammond border and Buffington Harbor, near a passenger rail track, shown on Jan. 19, 2026, is one of three sites proposed by Indiana for a future Bears stadium. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

A 400-acre site east of Clark Street in Gary, pictured on Jan. 19, 2026, is one of three sites proposed by Indiana for a future Bears stadium. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Show Caption

1 of 3

A site on Lake Michigan near Miller Beach, pictured on Jan. 19, 2026, is one of three sites proposed by Indiana for a future Bears stadium. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Morgan and others were prepared for an opportunity that arose quickly. On Dec. 17, a little more than three months after the Bears announced their intention to finalize Arlington Heights as “our future home,” team President Kevin Warren told the Tribune that plans had changed.

The cooperation the Bears expected from Illinois lawmakers had not materialized. The team had been waiting on that cooperation — on local and state assistance with building infrastructure in Arlington Heights, and on what Warren described as “reasonable property tax certainty” — for more than a year.

“We listened to state leadership and relied on their direction and guidance, yet our efforts have been met with no legislative partnership,” Warren wrote in an open letter to fans, before getting to the crux of it all a couple of paragraphs later: “We need to expand our search and critically evaluate opportunities throughout the wider Chicagoland region, including Northwest Indiana.”

In Illinois, Gov. JB Pritzker and state legislators have scoffed at the possibility of the Bears playing their home games across state lines. But Pritzker also recently hired outside counsel to advise his administration on the Bears’ demands of state lawmakers, while Arlington Heights Mayor Jim Tinaglia has urged the legislature to make a deal.

The state of Indiana, for its part, has appeared happy to oblige. A proposed bill with widespread support in the Indiana state legislature would create the “northwest Indiana stadium authority” to acquire land and “construct, equip, own, lease, and finance” a stadium for the Bears, who could then purchase it for $1 after a 35-year lease.

A spot in Hammond, just across the state line, immediately became a leading contender for a stadium site and Indiana Gov. Mike Braun made no secret of his desire to lure the Bears out of Chicago. And in Gary, where City Hall is surrounded by crumbling buildings and the abandoned Genesis Convention Center, elected officials and the city staff went to work.

On Dec. 18, the day after the Bears’ northwest Indiana announcement, Gary Mayor Eddie Melton promised “a comprehensive proposal” to bring the team to the city. Four weeks later, Gary released renderings for three proposed stadium sites: one near the Hard Rock casino, another close to the construction of a FedEx distribution center near Buffington Harbor and the one in Miller Beach.

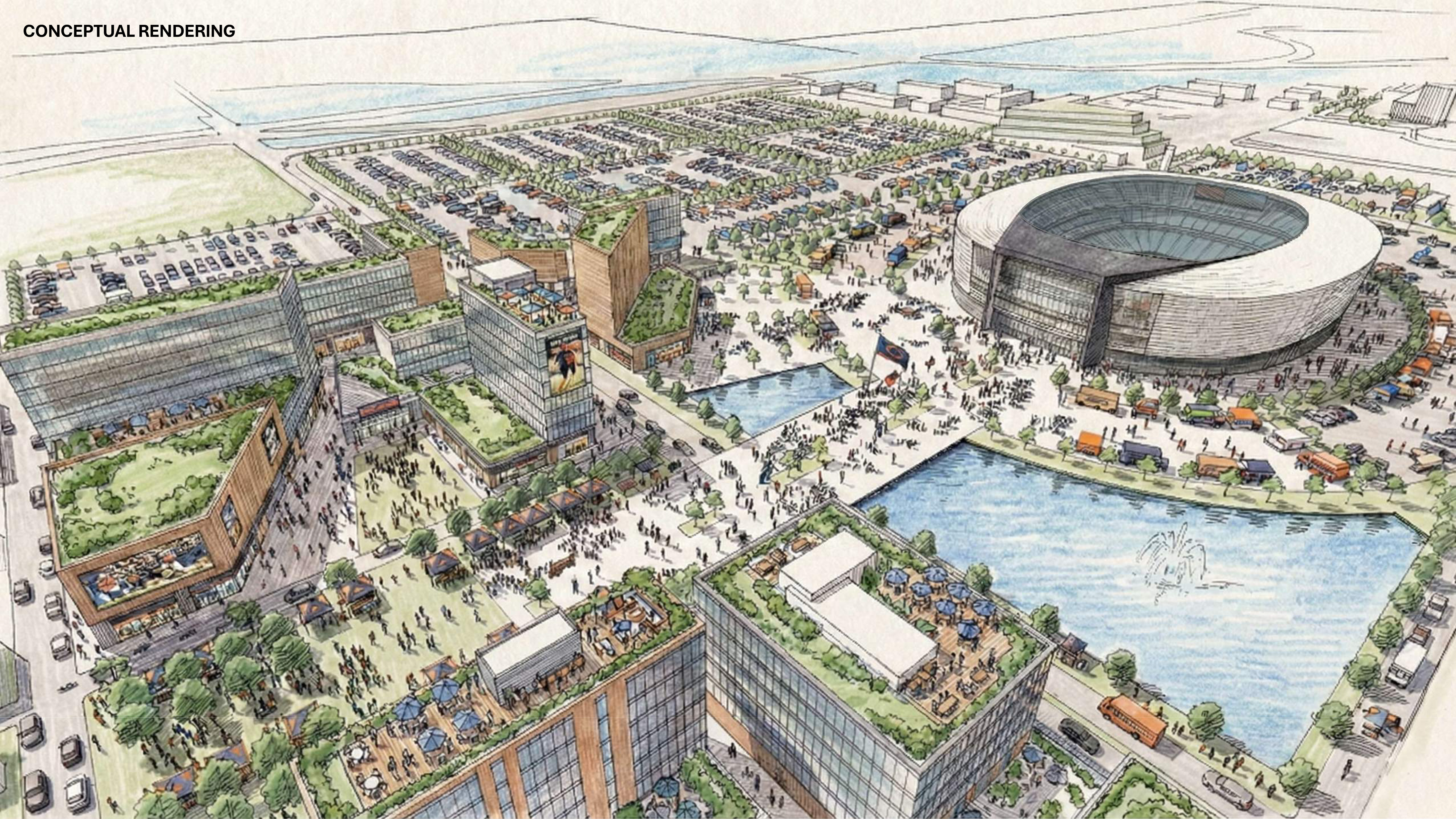

A conceptual rendering released by the city of Gary shows a potential Chicago Bears stadium and entertainment district. (City of Gary)

This conceptual drawing released by the city of Gary shows a promenade district adjacent to the proposed Chicago Bears stadium. (City of Gary)

A city of Gary rendering shows the proposed Chicago Bears stadium, promenade and entertainment district. (City of Gary)

Show Caption

1 of 3

A conceptual rendering released by the city of Gary shows a potential Chicago Bears stadium and entertainment district. (City of Gary)

The plans came in a slickly packaged press release, with a title Melton and others hope to speak into existence: “The Ultimate Comeback Story.” The Bears, though, have not necessarily singled out Gary as a contender. The franchise has chosen the words of its statements carefully, and referred to “northwest Indiana” only in the collective.

That was the wording, again, of a recent Bears statement after the Indiana stadium bill advanced out of the Senate, with the team describing it as “another positive and significant step toward building a world-class stadium in Northwest Indiana for Chicago Bears fans and all of Chicagoland.”

The intentional vagueness has hardly tempered optimism among Gary leaders.

“The day that they officially made the announcement,” Morgan said, referencing Warren’s open letter in mid-December, “I’ve been saying since that moment — it’s ours to lose.”

During a recent tour of the sites, Morgan and Chris Harris, Gary’s executive director of redevelopment, were eager to show what the city has to offer. At the lakefront site along Miller Beach, they’d arranged for heavy-duty golf carts, replete with thick tires, to provide transportation over the dunes and frozen sand.

The ride ended at the west end of the beach, in front of a rock wall that juts into the lake. The wall divides Lake Street Beach from Gary’s enormous U.S. Steel campus. For more than 100 years, Gary’s fortunes have been tied to the mill. The rise of U.S. Steel gave rise to the city. The decline of the mill, and decades of cuts, hastened Gary’s fall and made it Exhibit A of America’s Rust Belt ruin.

If there’s to be an ultimate comeback story, it’d be appropriate for it to start here. Yet there’s still that impossible-to-shake question of whether a place that’s already been through so much might just be on the other end of another indignity, with the Bears using the threat of moving as a bargaining chip to acquire what they really want.

As a Gary parks employee powered one of the carts through the dunes and onto the beach on another wind-swept and freezing February day, he posed the question that has been a lot of minds in Gary amid all the stadium talk: “You think it’s just leverage?”

In Warren’s Dec. 17 letter he denied the obvious inference.

‘We’ll gladly have them’

“This is not about leverage,” he wrote of considering sites in northwest Indiana.

Gary has been here before, though. In the mid-1990s, when the Bears were pursuing a new stadium that never came to fruition, franchise leadership expressed a willingness to consider northwest Indiana. A site in Gary, near the maze of concrete where Interstates 65 and 94 connect, was among the possibilities. Or so that’s how it was sold.

“My first impression might be that it is part of the jockeying the Bears are doing with Chicago,” then-Gary Mayor Thomas V. Barnes said at the time. Soon enough whatever hopes Gary and the region might’ve shared fizzled.

If there’s a difference now, it might just be in how optimistic Gary’s leadership is. And it might just be in how openly frustrated the Bears have grown with Illinois lawmakers.

Darren Washington, a member of the Gary Common Council, rubbed his hands together and smiled when he recalled hearing that the Bears were open to northwest Indiana. He learned about it from Warren’s December letter and he took note of the claim that Illinois’ “state leadership” informed the Bears that an Arlington Heights stadium package “will not be a priority in 2026.”

As he recited that line, Washington’s eyes widened.

Darren Washington, a member of the Gary Common Council, stands on Feb. 5, 2026, at Fifth Avenue and Broadway in downtown Gary. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Darren Washington, a member of the Gary Common Council, stands on Feb. 5, 2026, at Fifth Avenue and Broadway in downtown Gary. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

“I was like, ‘Are you serious?’” he said of the thought of Illinois lawmakers not prioritizing a stadium deal. “I’m like, ‘OK, if you want to throw them away, we’ll gladly have them.’”

Washington is among those Gary leaders who’s a believer. On a recent snowy Thursday, he’d come to a newly opened Dunkin’ not far from Miller Beach to share his belief. He invited Kenneth Whisenton, another member of the city council, and both men laid out the vision shared by other council members and by Melton, whom Washington likes to call “Mayor Momentum.”

Melton, 45, has been Gary’s mayor since 2024. Like many among the city’s leadership, he’s a native who appears intent on guiding a rebirth. He did not make himself available to be interviewed for this story but those close to Melton, including Washington and Morgan, the city attorney, praised him for his relationship building.

Melton is a former college football player and a Democrat with a reputation for working well with Indiana’s Republican leadership. He also has built a productive relationship with Warren, the Bears’ president, Morgan said.

On the city council, Washington and Whisenton are representative of the hope in Gary. They’re both natives with deep family ties to the city. Washington, 56, grew up in a two-parent home dependent on the steel mill where both of his parents worked. His mom suffered a fate familiar to many with family who worked in the mill, and died of cancer. His father was laid off at the mill in the 1980s and then went from “job to job.”

“He always made sure that home was taken care of,” Washington said.

As Washington grew older, Gary entered into its prolonged decline. Downtown became a place of vacant storefronts and abandoned churches. The city’s reputation nosedived.

Whisenton, meanwhile, grew up in the version of Gary that was left behind. He was just a kid when the city became known as the murder capital of the USA, and though in some ways that reputation might’ve been unfair, he carries the scars of growing up in a forsaken place.

“I’ve had plenty of friends murdered,” he said. “I can’t tell you (how many). I’ve been to more funerals than weddings. It’s ridiculous. I’ve been in so many obituaries.

“I’ve got a picture of my best friend in my truck. Committed suicide.

“It’s this environment. It’s rough.”

Yet both men chose to build a life here after college and career opportunities elsewhere.

As they talked about the Bears and the city’s hopes, a woman at the next table over interjected. She said she was in the final stages of buying a house nearby. She’d found a good deal in a good neighborhood, she said. And as a Bears fan, she’d heard about the stadium possibilities. She wanted them to move to Gary, too, and hoped it wasn’t just talk.

Setting a positive image

Tyrell Anderson stood in the snow outside the long-abandoned Union Station, which for decades has slowly deteriorated near the entrance to U.S. Steel’s flagship Gary Works plant. Anderson works at U.S. Steel but is a passionate photographer who became a preservationist by accident.

Gary native and steelworker Tyrell Anderson founded the Decay Devils, a group that has done restoration work in Gary. He’s in front of Gary Union Station on Feb. 5, 2026. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Gary native and steelworker Tyrell Anderson founded the Decay Devils, a group that has done restoration work in Gary. He’s in front of Gary Union Station on Feb. 5, 2026. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

A group he founded, the Decay Devils, now owns Union Station. For years there have been plans to revive it. To build a museum within, or maybe a coffee shop and art space. But then came the pandemic and the disruption of funding and a series of false starts with the city, and the old train station, a significant part of Gary’s history, continues to sit.

Fifty-five years after its closure it remains a metaphor. A reminder of how difficult it can be to bring a storied past back to life. Proof that in Gary, even the best intentions can take a while to become reality, if they ever do. The talk of a Bears stadium has left Anderson, 40, concerned. He’s a Gary native who returned after college at Purdue. He has heard talk of big plans before.

“I’m torn for a lot of reasons,” he said, and not just because of his affinity for the Packers. He questioned the incentives Indiana is willing to concede despite cuts in other areas, including school funding. He didn’t necessarily buy the notion that an NFL stadium attached to an entertainment district would fix Gary’s woes.

And he wondered about unintended consequences. He said his grandmother, who suffered burns when she worked in the mill, lost her house just down the street when the city seized the land to build a minor league baseball stadium. What would be disturbed or disrupted if the Bears really did pursue doing something near Hard Rock casino or Buffington Harbor or Miller Beach?

Around Gary, reactions to the prospect of a Bears stadium have ranged from a kind of show-me incredulity — “that (expletive) ain’t gonna happen,” Bruce Evans said, while manning the bar one quiet Sunday afternoon at 18th Street Brewery’s Miller Beach location — to optimism that maybe even being in the conversation is a good sign.

Cindy Klidaras, owner of Great Lakes Cafe in Gary, on Feb. 4, 2026. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

Cindy Klidaras, owner of Great Lakes Cafe in Gary, on Feb. 4, 2026. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

“We need to boost some revenue around here,” said Cindy Klidaras, the owner for 32 years of the rustic Great Lakes Cafe near the U.S. Steel campus.

The diner on a recent Tuesday at lunchtime was packed, full of steelworkers and cops Klidaras knows by name. She pointed out a couple of men at a table in the back in from Japan, and Nippon Steel, which recently acquired U.S. Steel and promised to invest billions in the Gary Works plant.

That deal, which local leaders have sold as a significant win for Gary, has resulted in cautious hope. So has a partnership with the University of Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, which has joined city leaders in effort to create and execute a downtown revitalization plan.

The city has suffered so much for so long, though, that the needs are many. During the driving tour of the stadium sites, Morgan, the city’s lead attorney, and Harris, in charge of redevelopment, highlighted what each location had to offer while navigating between swaths of blight.

Harris tracks the number of properties in need of demolition on a map on his tablet, and though that number is slowly decreasing, anyone driving along Broadway and into downtown can see what remains: boarded-up building after boarded-up building; skeletons of roadside marquees for bygone businesses; blocks of ruin signifying a lost city or opportunity, depending on one’s perspective.

The city has recently demolished three buildings near downtown, Harris said, and there are plans to clear dozens more this year. The list is long, though.

“We’ve identified 2,300 structures that need to be demolished through the Indiana Unsafe Building Law,” Harris said. Between state funding and grants, the city had procured $17 million to address blight. How much of a difference could it make? And how soon?

“Within the next year and a half, you’ll see a significant difference in the amount of blight in the downtown core,” he said. “But we’re going to continue to move forward south along Broadway, into the midtown neighborhood, and clearing out blight from the viewshed of Broadway, so we can set a positive image for the city.”

As Morgan navigated back toward City Hall, she turned into a parking lot across the street from the Genesis Center. To the left stood an old brick building, several stories high, with missing windows and a crumbling exterior. It was “too far gone to save,” Morgan said, and through the Notre Dame partnership there were plans to knock it down and build new.

That has become a significant part of the calculus in Gary in recent years: Identifying places worth saving. Letting go of ones that aren’t. Fighting for what might be possible. And so city leaders are fighting, however long the odds, for a Bears stadium that they believe would accelerate a rebirth.

The land is there. The vision. The most hopeful can see it, however improbable: the Bears in Gary, maybe even right on the lake near the mill, the lights of Chicago not too far in the distance.