The hiring of a head coach is the biggest decision a football organization will make, and yet all too often the hiring boils down to factors that have nothing to do with football. The umbrella term for this is “politics,” and it most commonly boils down to the individual motivations of those influencing or making the hire. How bad will the executive look if an unconventional candidate gets the job and fails? What if a candidate popular within a faction of the hiring committee succeeds or the community at large is voted down and succeeds elsewhere?

So often, the decision isn’t What’s best for our football team? but What hire will be least risky for my personal career?

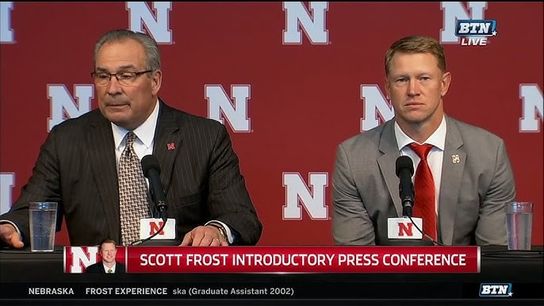

Rarely do we see this dynamic laid out so clearly as Nebraska’s ultimately doomed hire of Scott Frost. Ultimately doomed probably isn’t the right term — the Frost era at Nebraska failed before it ever started, and both sides knew it.

Former Huskers AD Bill Moos has released his memoir, Crab Creek Chronicles: From the Wheat Fields to the Ball Fields and Beyond, which tells the former All-Pac-8 offensive tackle’s side of the story across a 40-year career in athletics administration, culminating in his run as Nebraska’s AD from 2017-21.

In an excerpt that was posted to social media, Moos described an interview with Frost that did not go well.

Frost insisted upon having Matt Davison — the receiving end of “The Catch,” which preserved Nebraska’s 1997 co-national championship — sit on in the interview. Davison worked in medical sales but remained connected to the program as its radio color analyst, and Frost later hired him as Nebraska’s associate AD for football.

Of course, that’s not the story Moos told the media back in December 2017.

“In the end, a lot of this was about integrity and how you go about your business,” Moos told ESPN. “It was easy. And that’s not the norm anymore.”

On one side of the table, you had an AD who knew his candidate wasn’t ready for that magnitude of a job, yet hired him anyway out of professional insecurity. On the other side of the table, you had a coach who didn’t really want to take the job, but took it anyway out of a sense of obligation to other people.

“I didn’t want to leave UCF,” Frost said last summer. “I always said I would never leave unless it was some place you could go and potentially win a national championship. I got tugged in a direction to go try to help my alma mater, and I didn’t really want to do it. It wasn’t a good move.”

And the cherry on top, Frost was never interested in Florida or Tennessee in the first place.

Frost left UCF in the midst of a 13-0 season — the news broke during the AAC championship game, a 62-55 double overtime classic win over Memphis at the Bounce House — and veered into a move that all involved knew, before it even began, was not right for either party. Frost was fired three games into his fifth season with a 16-31 record, but he lasted longer in Lincoln than Moos, who was paid $3 million to go away in 2021. Neither Frost nor Nebraska football are in better places today than they were in December 2017.

For what it’s worth, the fit seemed so blindingly obvious to most of us back in 2017 that the public pressure on both Frost and Moos to make this happen was immense. Only years later can both men involved now admit that it was just easier to give in to the peer pressure and go through with their obviously-dysfunctional marriage than to call the wedding off. That’s politics, and that’s also human nature. And nearly a decade later, it’s still shaping the fortunes of two Power 4 football programs.

And speaking of that, Moos also went into great detail about a serious pursuit to leave the Big Ten and re-join the Big 12. We don’t have dates here, but from context this appears to be before Texas and Oklahoma left the conference for the SEC…

… and that high-level forces nearly succeeded in getting Nebraska to cancel its home-and-home with Oklahoma.

That singular non-conference football game — a 23-16 win by No. 3 OU over a Nebraska team that, just as Frost apparently feared, finished 3-9 — may have been the most consequential in college football history. While Nebraska was in turmoil of whether or not to even play a game in which it feared it would be blown out, Oklahoma was furious that Fox would not allow the kickoff time to be moved from 11 a.m. to prime time. The school publicized that it was “bitterly disappointed” with Fox, and less than two months later the Sooners, along with Texas, agreed to join the SEC. OU president Joe Harroz later admitted that the Big 12’s TV contract was the reason why. The Nebraska game — which was almost never even played — was the final straw.

What were we talking about? Oh, yeah, Frost insisting on Davison sitting in on his interview with Nebraska. None of that has to do with the original point of this article, but it was too fascinating not to write about.

To close, there are two lessons here for athletics directors at all levels of football:

1) No matter how difficult it may seem in the moment, you will instantly regret allowing external political forces to arm-twist you into a hire you know in your gut is wrong.

2) If Point No. 1 happens anyway and it inevitably costs you your job, write a memoir about it.