Editor’s note: All week, The Athletic is writing about college football rivalries at a moment of change in the sport. Read our ranking of the top 100 rivalries here and also vote for your favorites.

The big, iconic hedges that surround its home field are a defining part of the Georgia football program. And as legend has it, Georgia can thank the kindness of the program that now serves as its nemesis: Alabama.

The story goes that Charlie Morton, who worked in Georgia’s athletic department in 1926, was invited by his Alabama counterpart to that year’s Rose Bowl to watch the Crimson Tide play on the West Coast. Martin came away so impressed with the rose hedges that when Georgia began building Sanford Stadium a few years later, Martin wanted some to be a part of the Bulldogs’ new home.

“But roses won’t grow well in this climate, so that’s when they switched to the (regular) hedges,” said Loran Smith, the official historian of the Georgia athletic department.

So that’s the legend, and nobody has challenged it over the last century. A century in which Alabama and Georgia have been two of the most prominent programs in college football, their showdowns over the last decade-plus becoming must-see television. And yet this matchup of two flagship schools in bordering states is not played every year. In fact, few in either fan base would consider the other one of their school’s top two or three rivals.

Or as Kirk McNair, a longtime Alabama writer and historian, puts it: “It’s a rivalry when it’s important.”

That has been the case in recent years and will be once again when they meet Sept. 27 in Athens. In nine of the last 10 meetings, dating back to 2008, both teams have been ranked in the AP top 10, and seven of those 10 times they’ve both been ranked in the top five. That includes two national championship games and four SEC championship games.

The series took on new meaning after Kirby Smart, who had been Alabama’s defensive coordinator from 2007 to 2015, became Georgia’s head coach, colliding with his mentor Nick Saban in many of those games. But even before that, the two teams played their share of classics, from the brutal (for Georgia) ending of the 2012 SEC championship, the infamous (again, for Georgia) Blackout game of 2008 and a number of memorable finishes between Bear Bryant and Vince Dooley’s teams.

So why has it not been an annual game? Some of it has to do with an infamous case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. Some of it is just simple geography.

Alabama and Georgia are border states, but the campuses in Tuscaloosa and Athens are more than 275 miles apart. One must drive through Atlanta and Birmingham, two major Southern cities, to get from one to the other. That was a hindrance to establishing a rivalry in the early days of college football. Auburn’s campus, for example, is a few hours’ drive closer to each. Georgia also has an in-state rivalry with Georgia Tech. Alabama and Georgia also developed heated rivalries with other border state schools: Tennessee (for Alabama) and Florida (for Georgia).

Their first meeting was in 1895 in Columbus, Ga., won by Georgia, 30-6. They met again in 1901, starting a 64-year stretch that featured 47 meetings. In those days, the SEC didn’t make the conference schedule, so schools decided who they played within the conference. So while Alabama-Georgia was not an annual rivalry, the ties between the programs — and geography — were close enough to make it a frequently played game.

Then came the Saturday Evening Post scandal.

A man accidentally overheard Bryant and Georgia athletic director Wally Butts talking the week of their 1962 game, and it led to a story in the Evening Post suggesting that the game had been fixed. Butts and Bryant both sued, with Butts’ case going all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in his favor. In the meantime, the contract to play the game ran out after the 1965 season, and it wasn’t renewed. The assumption over the years has been that it was because of the scandal, but Smith doesn’t think that’s entirely accurate.

“I just think inaction sort of took over,” he said. “I don’t remember any nasty energy, ‘We don’t want to play them,’ anything like that.”

Alabama dramatically beat Georgia for the 2017 national title in OT. (Streeter Lecka / Getty Images)

In fact, there was a lack of animosity between the two programs and schools. That may have contributed to the series not being prioritized — they didn’t play against until 1972. They did play a memorable game in 1965, when Dooley got the first big win of his tenure, 18-17 in Athens. A year later, at an SEC coaches meeting, Bryant put his arm around Dooley’s wife and told her: “Young lady, don’t you forget that I’m the man that made your husband famous.”

Bryant got his revenge in 1972, despite Georgia fans pulling the fire alarm at Alabama’s hotel in Athens and riding by it constantly, blaring horns. Dooley did beat Bryant four years later in Athens.

But the teams didn’t play from 1978 through 1983, meaning Alabama didn’t match up with Dooley’s best teams, including the 1980 national champion. They played eight times from 1984 through 2003, periods in which the two programs weren’t often both good. Only once in that period were both ranked when they played: 2002, when No. 7 Georgia won at No. 22 Alabama, 27-25.

Everything changed when Saban arrived.

At first, Georgia got the upper hand. Mark Richt’s 22nd-ranked Bulldogs won in Tuscaloosa, 26-23 in overtime. The next year, Saban started his seven-game win streak, almost all memorable games. Smart, who was born in Montgomery, Ala., finally ended the streak in the 2022 national championship game. But he has lost the last two, including last year’s 41-34 game in Tuscaloosa, the first after Saban retired.

This year, Smart gets to face Alabama in Athens for the first time. Going forward, the two will play twice every four years. In the new SEC scheduling format, if the conference stays at eight games, every team will have one designated annual rival. Alabama gets Auburn, and Georgia gets Florida. If they go to nine games, then every team gets three designated annual rivals, but Alabama-Georgia is not expected to be one of them.

“I don’t think it’s enough of a rivalry to warrant a feeling of animosity,” said McNair, who was Bryant’s sports information director and now writes for a 247Sports site covering Alabama. “Now, also, when you’re winning like Alabama’s doing the last few years in the Saban era, you don’t really have animosity. It’s usually from the other side.”

Which is how Georgia fans have viewed it. Alabama as the nemesis, from the Blackout game to the 2012 SEC championship, to second-and-26, then finally beating Alabama after Kelee Ringo’s pick-six … only to lose twice more to the Crimson Tide.

Tony Barnhart, who is retiring later this year after 50 years covering the SEC, was standing on the sideline for the iconic second-and-26 play in the 2017 national championship game. Alabama and Georgia are not rivals in the traditional sense, Barnhart agreed. They’re measuring sticks for each other now.

That figures to be the case again this year.

“I would say the atmosphere in Dooley Field at Sanford Stadium on Sept. 25 will be electric,” Barnhart said.

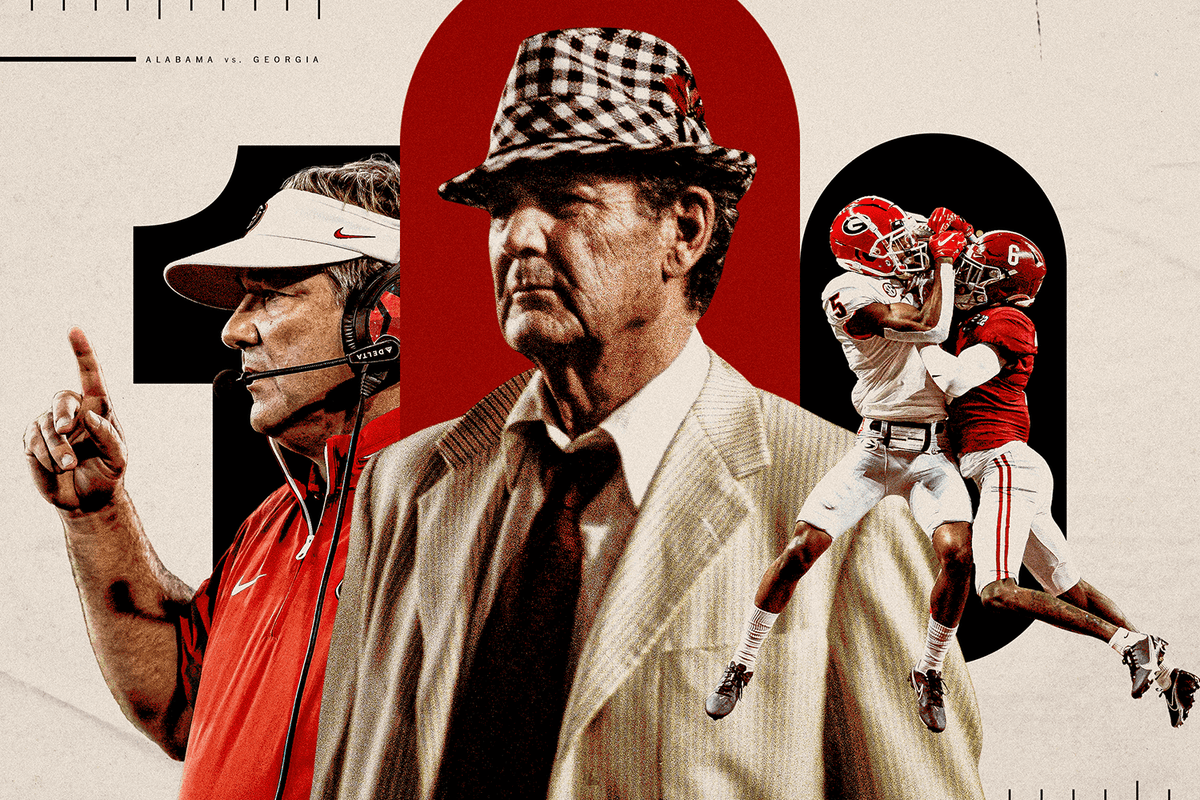

(Top image: Illustration: Will Tullos / The Athletic; Focus on Sport, Michael Hickey, Carmen Mandato / Getty Images)