Krifka Steffey, then the director of newsstand sales for Barnes and Noble, was holed up in her New York City apartment on June 5, 2020, when her husband, Jay, shouted to her from the other room with some alarming news from Twitter.

College football guru Phil Steele, citing the uncertainty over the upcoming season due to the COVID-19 pandemic, announced he would not be selling his college football preview magazine on newsstands that year.

Steffey gave her team an urgent mission: Hunt down Phil.

“I was like, ‘Uh-uh, he’s going to make this magazine,” she said.

That’s because Steele’s publication, despite coming out just once a year, brings in more revenue for Barnes and Noble than any other magazine.

“And the crazy thing about that,” said Steffey, “is Barnes and Noble stores are in all 50 states, 630-ish stores, and copies will sell in every single store.”

She made him a sweetheart deal, offering to eat the costs of any unsold copies. Steele delivered the magazine a month later, and still does every year.

Despite the ever-increasing dominance of digital media, the annual summer rite of preseason college football magazines has endured.

There are far fewer options than 20 years ago, but Phil Steele, Athlon and Lindy’s still have loyal audiences eager to scarf down season previews and prognostications for 130-plus college football teams. And football fans in Texas still buy up Dave Campbell’s Texas Football, a staple since 1960.

“The printed magazine is a quicker, easier reference than even the Internet. The information is in the same spot on every page for every team,” said Steele, whose 2025 edition spans 360 pages. “If you want to know a score from three years ago, you know exactly where to look. You can close your eyes and point your finger.”

That’s despite changes not only in content consumption today but changes in college football altogether: The early-summer publication dates, coupled with the transfer portal, make for some unavoidably outdated information. For example, Jake Retzlaff, who left BYU for Tulane last month, is still listed as the Cougars’ starting quarterback in the magazines.

As they say: Don’t underestimate nostalgia. Preseason magazine enthusiasts — even 20-somethings — wistfully recall growing up paging through the colorful pictures, cover-to-cover stats and projected depth charts.

“I come from a big Purdue family, and that was summer at our house, getting the Athlons and Lindy’s and reading through them,” said Jordan Jones, 26, from Warsaw, Ind. “We’d talk ourselves into how we thought Purdue was going to be better than prognosticators thought.”

“There’s something satisfying about having the physical magazine to read while sitting outside on the deck, next to a lake, or while on a vacation that I find more enjoyable and nostalgic than pulling up the same thing digitally on the iPad,” said Iowa fan Derek DeVries, 29.

Chase Clemens, 32, said he brought Phil Steele with him on an Army deployment to the Middle East in 2022.

“My dad got me hooked when I was about 14,” he said, “and Steele has been helping me power through the dog days of summer ever since.”

The magazines are understandably popular with gamblers; once upon a time, they were loaded with ads for 1-900 betting hotlines. They make for great bathroom reading. And there’s one particularly devout group of readers, said Lindy Davis, publisher of Lindy’s annuals.

“We get a ton of prison orders,” said Davis, whose 2025 magazine spans 264 pages. “They’ve got a lot of time to read, right?”

Preseason college football publications date back to at least 1891, with the book Spalding’s Official Football Guide, edited by Walter Camp. It began as largely an explanation of the rules but came to include reviews of the previous season by region, team photos and schedules. A few copies from the early 20th century can still be found on eBay, ranging from $20 to $100.

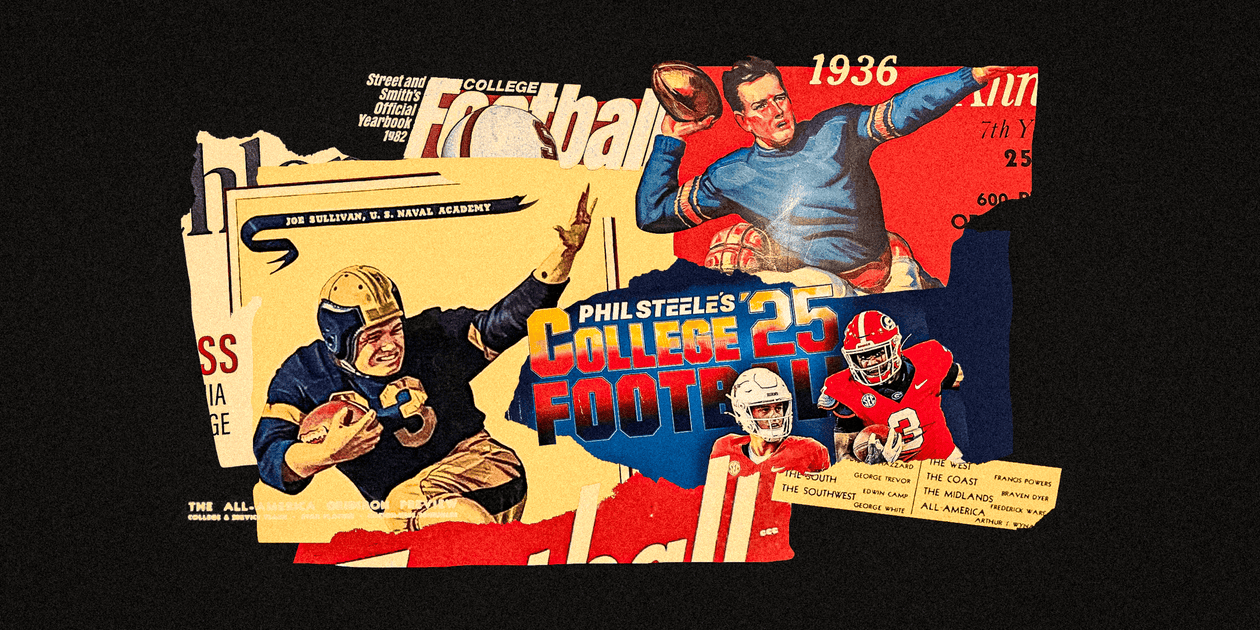

The first preseason magazines emerged by the 1930s, with titles like Illustrated Football Annual and Stanley Woodward’s Football. (Woodward was sports editor of the New York Herald Tribune.) Street and Smith’s, which became an institution, launched in 1940. Others like Athlon and Game Plan came on the scene by the ’70s. Lindy’s and Sporting News launched in 1982, Phil Steele in 1995.

By the late ’90s and early 2000s, Athlon was selling more than 700,000 copies in college football alone, in addition to NFL, fantasy football and other major sports.

As with other magazines and newspapers, most college football preview magazines did not survive the Internet age, when print advertising largely evaporated. Street and Smith’s folded in 2007 when it merged with Sporting News, which itself went digital-only in 2012. Game Plan ended in 2014.

Those that survived had to adapt. Grocery, pharmacy and big-box retail chains have either scaled back their newsstands or ditched them altogether. Steele now works with Barnes and Noble exclusively.

“Walmart used to have 60-foot racks in front of the store. Now they’ve got a four- or eight-foot rack,” said Davis. “So you can imagine what kind of impact that would have.”

But one trend works in their favor. Where newsstands were once the domain of sleek weekly publications like Sports Illustrated and People, now they’re filled with thick, one-off special editions devoted to celebrities like Taylor Swift and Caitlin Clark. Or cats. They’re both cheaper to produce and higher-priced. Much like a once-a-year college football magazine.

Steele bumped his price from $12.99 to $19.99 in 2020 and has seen his profits increase. “Anybody who’s had the magazine needs the magazine,” he said. “I really think if it was $25 or $30, people would still buy it.”

Steele declined to provide current sales figures but insists they’ve remained steady. A 2014 New York Times article said his circulation a decade earlier was 200,000. He now prints 150,000 but says the sell-through rate is higher. The magazine is also available in digital form, but those account for less than a quarter of its sales.

Davis, who publishes both a national edition and SEC and Big Ten regional editions, estimated around 85,000 sales last year. “We sell 60-65 percent of what we used to sell at our height,” he said. “That’s very good, by the way.”

Athlon did not disclose sales figures, but they are likely far less than their peak in the years surrounding the turn of the century. The company came the closest of the three to folding earlier this decade, by which point it had pared down to just NFL and college football, with no advertising.

But The Arena Group acquired the brand as part of its 2022 purchase of Parade. After losing its licensing rights to Sports Illustrated in early 2024, the company turned its focus to Athlon and has since doubled down on print. In the past year, it’s published preview magazines for NASCAR, MLB, the Premier League and the NBA and WNBA.

“Print is about giving sports fans a physical experience; let them hold and smell the product,” said Paul Edmondson, CEO of The Arena Group. “Our goal is to get Athlon Sports on every newsstand across the country and in as many hands as possible.”

It remains to be seen whether the next generation of fans will still appreciate that print experience.

“Our average age is probably getting about a year older each year,” said Davis.

Nebraska fan Nic Rhode, 32, said he began reading preview magazines in the late ’90s but now primarily consumes college football via websites and podcasts. “These days, I think I still buy magazines mostly out of tradition,” he said. “It’d feel wrong not to.”

On a recent trip home, he handed his copy of Athlon to his dad.

“He still uses a flip phone and barely touches the internet. I’m not even sure he knows what a podcast is,” said Rhode. “Watching him sit quietly in his chair reading this year’s Athlon gave me a real sense of joy.”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; images courtesy of Matt Brown / The Athletic)