“The stuff I’ve studied shapes how I view the world,” Kwesi Adofo-Mensah says.

Numbers, you mean.

“Yes. I love math because I’m comfortable with it. If you talked with me long enough, it’d probably come up.”

Is there a but?

“I love football, too. I’m just a normal-ass dude who loves football and decision-making. That’s it. Normal-ass dude.”

This feels like the perfect place to start.

Months earlier, the 43-year-old Minnesota Vikings general manager had declined an invitation to share his story. “If I’m being honest, I’d rather not talk about myself,” he said at the time. Adofo-Mensah is, by his admission, a private person occupying a front-facing position. He’d rather talk about his players and coaches. And besides, until the Vikings do what he came here in 2022 to do — hoist the Lombardi Trophy — who cares what he thinks?

But why not talk about his growth as a general manager? Why not share the sources of his passions for football and forecasting? Why not lift the curtain, at least a bit, on a unique life and career arc?

Eventually, he relented.

In some ways, Adofo-Mensah is similar to so many other NFL decision-makers. He, too, is maniacally competitive. He hasn’t forgotten the name of a kid who replaced him on the Cherry Hill East (N.J.) High basketball team when he was a sophomore. An almost defiant belief in himself? Angst over time spent away from family? These qualities are evident throughout NFL front offices.

At the same time, Adofo-Mensah is also undeniably different. It’s not just that he entered the professional sports ecosystem through the world of analytics. He is the son of Ghanaian immigrants. He got his bachelor’s in economics from Princeton and did his master’s at Stanford.

It’s his uncommon former job. He was a commodities trader on Wall Street long before working in football.

It’s his almost surprising personality. He’s not the quiet, hunched-over-a-computer stereotype that follows folks with his background.

Calling himself a “normal-ass dude” is his way of trying to connect to others in the insular NFL world. It isn’t a new challenge. He encountered people with dismissive attitudes in his first job with the San Francisco 49ers. There were skeptics when he worked for the Cleveland Browns, too.

No matter. He doesn’t mind working hard or explaining why his worldview is the way it is.

“How I approach problems will always be from a decision-making under uncertainty, heuristic-y, math-y world,” Adofo-Mensah says. “But my thought is … so does everybody.”

He points to the wall behind him, at the office next to his. That is where head coach Kevin O’Connell spends so much of his time.

“Kevin has an incredible mental model,” Adofo-Mensah says. “Every coach I’ve ever met, I look at how they call games. They look at the tape. They study what they do the most. That’s counting. I probably talk about it more because I’m passionate about it, and maybe there’s some kid like me out there who loves this stuff.”

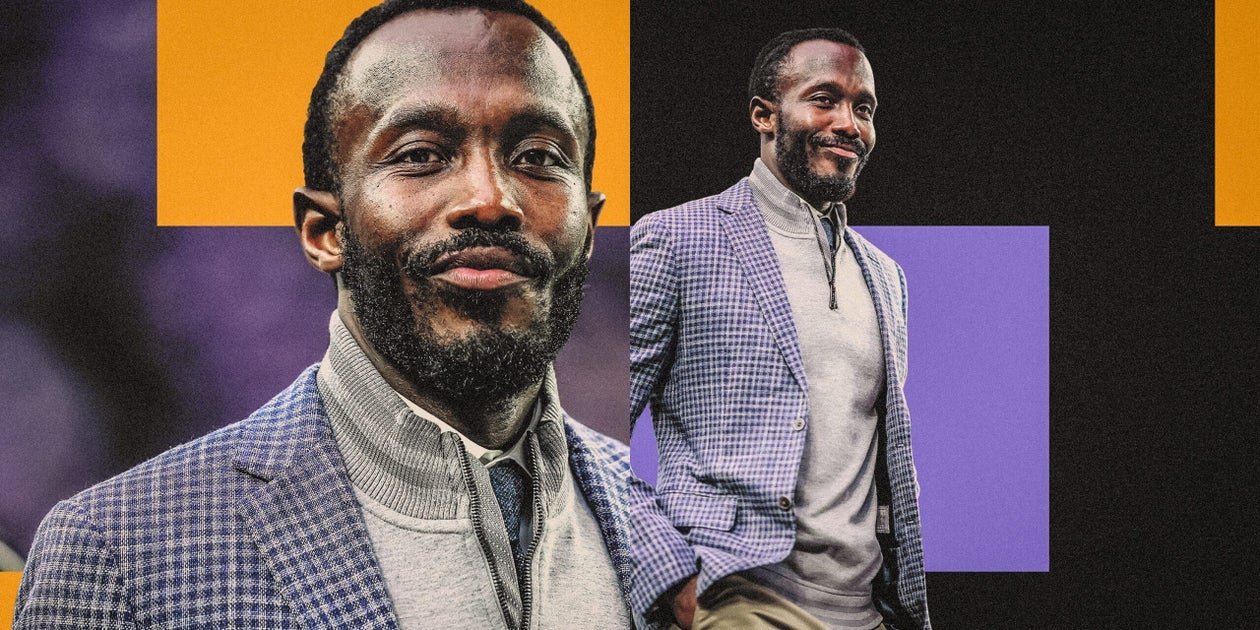

Calling himself a “normal-ass dude” is Kwesi Adofo-Mensah’s way of trying to connect to others in the insular NFL world. (Courtesy of the Minnesota Vikings)

In 2021, while Adofo-Mensah was the vice president of football operations in Cleveland, the Carolina Panthers requested to interview him for their open general manager position.

He was shocked.

“I was like, ‘GM?’” Adofo-Mensah, then only 39, says.

He inferred that Panthers owner David Tepper, a longtime hedge-fund manager, probably saw the promise in his analytic background. When Tepper ultimately passed on him, Adofo-Mensah told Andrew Berry, his then-boss with the Browns, “You’ve got me as long as you want me.”

“Tepper was the only guy I thought would hire someone like me,” Adofo-Mensah says, “and that was more than fine.”

The Vikings proved him wrong the following year. Co-owners Zygi and Mark Wilf sought a progressive thinker who would make purposeful moves and help reshape the vibe in the building. They chose Adofo-Mensah, who is refreshingly open about how much he has learned in the three years since.

It’s not that the Vikings haven’t had success. They’ve won double-digit games in two of his three seasons. The team has also become revered by players for the resources it provides and the way it treats their families.

Most of these accomplishments fill the young GM with pride, but the lack of playoff victories is not lost on him, either. He is wired to think about what more he could have done, areas in which he could be better.

Drafting is one of them. Adofo-Mensah hasn’t hidden from the flop that was his first go in 2022. Only one of his six picks remains on the roster. He acknowledged that he tried to do too much and has only grown more mindful of “system fit.”

Managing varying opinions among the staff is another. “I do think at times in this job you have the choice between doing things one way — making the decision you think is best — and making people feel good,” he says. “That is a constant dynamic in this job. If you keep doing things that make people feel good, you’re not going to be doing this job very long.”

Speaking to the media is one of the more delicate requirements of the position. This wasn’t a key component of his role in San Francisco or Cleveland. It has taken time.

“Everything good that’s ever happened to me in my life is from swallowing the hard pill and saying, ‘Get better,’” Adofo-Mensah says. “I’ll just never be another way. I do think there’s a certain type of malleable person who can at least emotionally intelligent their way through things. And if they mess up, they can say, ‘I messed up. How do I not mess up again?’ That’s what the job requires.’”

This perspective is one of the reasons Vikings ownership extended his contract in May.

And where does the perspective come from?

“Our parents,” Adofo-Mensah says. “Effort was not a choice.”

Mom and Dad emigrated separately from Ghana, met on the East Coast and raised their three kids in South Jersey.

As a child, Adofo-Mensah did what so many brothers do. He fought his brother and sister for the remote so he could watch the nearby Philadelphia Eagles.

He loved sports, but basketball was his favorite. Maybe the most formative event of his childhood, something he says he still thinks about weekly, is when a coach sat him down and told him he was no longer needed on the high school team at Cherry Hill East. “I can tell you exactly where I was sitting,” he says.

He spiraled. Got down on himself. Lost some sense of direction. The coaches noticed and offered him a spot back on the team. He told his mother, who asked if he’d done the necessary work to prove he was worthy of a spot.

Her response hammered him between the eyes. It was the last time he felt sorry for himself when it came to something under his control.

His mother was also the one who demanded he complete the application to Princeton. That’s where he met one of his closest friends, Mike Chernoff, currently the GM of the Cleveland Guardians. It’s where he studied economics, which presented him with the opportunity to work on Wall Street.

“He could have done anything in the world,” Chernoff says. “He got an A-plus on his Princeton thesis. And we’re like, ‘Wait a minute, Kwesi, how did you do that?’ We knew he was smart, but he was unbelievable.”

First, Adofo-Mensah traded sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide. Then a colleague named Trevor Woods, a longtime executive at J.P. Morgan and Credit Suisse, poached him as a partner to help develop a portfolio of investments. Woods credits Adofo-Mensah for putting the kibosh on the deal that could have cost the firm nearly $1 billion.

“We had all of these senior staffers yelling at us to do the deal,” Woods says. “He said, ‘No. We’re not doing that.’ It wasn’t a personal thing for him. It was just business.”

Not all of the days went that way. Some investments tanked, and members of the firm would find themselves at New York City bars afterward, reeling. Adofo-Mensah would sit there and wonder what he missed in the numbers or in his research. Sometimes, it was nothing. A cold front arrived and sideswiped an energy investment that had been doing well.

He was living in the world of probability. Being 60 percent confident in an investment might win over the long haul, but that 40 percent chance of failure is always lurking.

“People tend to operate like there is certainty,” Adofo-Mensah says. “I know the world isn’t that way because I used to do it for a living.”

He still maintains that he loved his former job — the stakes, the relationships, the sense of accountability. But by the late 2000s, he wanted to do something different. Try a new challenge. Work toward a goal with another group of people.

“I didn’t want that to be all my tombstone read,” Adofo-Mensah says. “That I went and made a bunch of people money.”

“Everything good that’s ever happened to me in my life is from swallowing the hard pill and saying, ‘Get better,’” Adofo-Mensah says. (Courtesy of the Minnesota Vikings)

After a master’s program at Stanford — he thought he wanted to be an economics professor — Adofo-Mensah was connected by Chernoff to Daniel Adler, the Jacksonville Jaguars’ director of research. Adler then referred him to Brian Hampton, the 49ers’ director of football administration and analytics.

The 49ers invited him for what felt like 80 interviews. He was eventually hired.

Your first football job. Football R&D analyst. What were you hired to do?

“They just said, ‘Go help somebody,’” Adofo-Mensah says.

Can you give me an example?

“A coach asked me, ‘Would you rather have a corner who is really instinctive without great movement skills or a guy who could match and cover but might give up big plays?’ To come up with an answer, I built a simulator.”

How?

He glances over at his computer.

Adofo-Mensah occupied a desk near the business department inside the 49ers’ facility. A contract administrator named Richard Buffum sat directly behind him. When Adofo-Mensah first arrived, Buffum skimmed his new colleague’s resume and saw what everyone sees: Princeton grad. Commodities trader on Wall Street. Stanford degree.

“The profile of him in your mind is an arrogant prick,” Buffum says. “I’m thinking, ‘I probably won’t like this person.’ I had to learn he was the opposite. That he has so much humility and grace and is so personable.”

Consider the significance here. Buffum was as data-inclined as most inside the building, and even he initially struggled with Adofo-Mensah’s presence.

Adofo-Mensah would detach himself from the world with headphones blasting techno music, venturing out into the spreadsheet wilderness. When he returned with new insights about NFL Scouting Combine data, NFL Draft hit rates, injury curves and draft pick value, few were there to listen.

One unexpected advocate surfaced: longtime NFL coach Eric Mangini, who had been hired by the 49ers as a consultant.

“I guess the one thing that initially hit me is, if he’s willing to give that old job up, then he’s willing to do the things that it takes to be successful in the league,” Mangini says. “He had a great situation. He had a great trajectory. He had gotten a very hard position to get. And he was willing to walk away from that to come here.”

In other words, he related to Adofo-Mensah’s boldness.

Adofo-Mensah’s role evolved over the years, from peppering Mangini about the New England Patriots’ old scouting reports to coding databases that would lead to proprietary pre-draft metrics. He moved from manager to director, culminating in projects such as organizational cultural studies, informed by everything from Bill Walsh’s archives to a book titled “The Fifth Discipline,” written by a professor at MIT.

It was a satisfying — albeit challenging — ride to the 2019 NFC Championship Game at Levi’s Stadium. That night, after a resounding 49ers victory over the Green Bay Packers, confetti fluttered onto the field.

Amid it all, children hugged their fathers, and many of the husbands hugged their wives. Adofo-Mensah, who had long positioned work above all else, noticed.

“I almost felt like, ‘Man, I’m missing that,’” Adofo-Mensah says. “I remember promising myself in that moment: ‘This is great. But for the rest of your life, you can’t keep choosing work over that.’”

A month after that NFC championship night, a lady named Chelsea — “the one that got away,” Adofo-Mensah says — called him out of the blue. They met for lunch. Their conversation lasted 10 hours.

All was going well until, not long after, Berry, the Browns’ general manager, reached out. He wanted Adofo-Mensah to be one of his assistant GMs. “I’m looking up at the sky like, ‘This is the test,’” Adofo-Mensah says. “I had a crisis.”

Berry, himself a husband and father, understood. Weighing whether to choose “life” after so many years of being all in at “work”? He had lived that existence. It wasn’t a jarring thing to hear from Adofo-Mensah, but it was revealing.

So, why’d you go?

“Chelsea said I had to,” Adofo-Mensah says. “She said, ‘I don’t know if we’re going to make it through it, but you have to do this.’”

That decision pushed the first domino in the next phase of his life. In Cleveland, he met Browns chief strategy officer Paul DePodesta (portrayed by Jonah Hill in “Moneyball”), a man who had experienced a similar journey two decades earlier with the Oakland Athletics.

The more work you do, the more wins you compile, the more correct decisions you make, the less relevant the nontraditional past becomes.

Adofo-Mensah could’ve worked with Berry forever, acting as something of a translator between the analytics staff and the talent evaluators. Most of his work centered on available free agents, weighing levels of risk based on everything from system fit to age to recent play.

He would eventually explain all of this to the Wilfs. What earned their approval, as much as anything else, were Adofo-Mensah’s convictions about the most critical aspects of the most successful NFL organizations — a finding that emerged from his studies with the 49ers.

“Of all the decisions you make,” Adofo-Mensah says, “head coach and quarterback are the two you need to not screw up.”

The Vikings orchestrated an intense search for the former, thinking that position could one day lead them to the latter. As part of the interview process, Adofo-Mensah asked O’Connell to pick a play and describe it from the idea to its execution.

Working with 49ers coach Kyle Shanahan helped Adofo-Mensah realize that an NFL head coach must be what he describes as “a systems thinker.” Essentially, he needs to make decisions knowing that every decision affects every other decision.

O’Connell brought up a pass from his Los Angeles Rams’ recent NFC Championship Game win and talked through everything, from the design to the protection to the completion. At one point, while O’Connell was winding and rewinding the play, Adofo-Mensah says he felt chills.

“It was, like, ‘Holy s—,’” Adofo-Mensah says.

Ownership paired the two together in 2022. Step 1.

Step 2, finding the quarterback, would occur a couple of years later. It’s not that the Vikings were waiting to move off of Kirk Cousins; his torn Achilles tendon in 2023 complicated the overall calculus. After that season, the Vikings’ leadership group held myriad meetings to design their plan. They were standing at a fork in the road.

“Quarterback was typically the marker,” Adofo-Mensah says. “Because quarterback associates with money.”

The decision-making under uncertainty, heuristic-y, math-y man thinks constantly about value and optionality. It’s why the Vikings have executed countless trades with pick swaps since Adofo-Mensah took over (see Cam Akers). It’s why they haven’t been afraid to take shots at low-cost signings with upside (a la Byron Murphy Jr.). It’s why they’ve spent money on youth when possible (signing Jonathan Greenard). It’s why they’ve been so intentional about positioning themselves for compensatory picks (three should be forthcoming in 2026).

Going the rookie quarterback route is the ultimate example. The Vikings believed they could build the best team over the long haul with the available resources the rookie contract allows for the rest of the roster. O’Connell led the charge on the evaluation, and the team landed J.J. McCarthy. Meanwhile, the Vikings used their newly created cap space on a free-agent bundle (Darnold, Greenard, Andrew Van Ginkel, Blake Cashman, etc.) that offered a ton of surplus value.

McCarthy’s torn meniscus came at a suboptimal time. Neither O’Connell nor Adofo-Mensah had been extended. But this had always been part of the bet, one Adofo-Mensah was willing to make to achieve the ultimate goal.

Kwesi Adofo-Mensah has found a partner in coach Kevin O’Connell. The two have a 34-17 record in their three seasons together. (Courtesy of the Minnesota Vikings)

Adofo-Mensah is back in his office, powering through another lunch. A mini basketball hoop sits in one corner. Scribbled on his whiteboard in blue ink is a message from one of his two young sons.

He has talked through the aftermath of the 2024 season and executed a strategy to revamp the team’s offensive and defensive lines. Though he’s excited, he’s also measured.

Now, the subject shifts.

“Yesterday was our son’s birthday,” Adofo-Mensah says. “We write him letters on his birthday every year.”

The we, to be clear, is he and his wife, Chelsea. Going to Cleveland did not doom their relationship. She hopped on board the roller coaster and has been a witness to all of it: the hits, the misses, the learning, the perceptions, the misperceptions.

What’d you write in the letter this year?

“Being your dad and a husband and the GM of this team for this town is a challenge you’ll never know,” he says. “It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But every day you do something that makes me think this is all the best thing I’ve ever gotten to do.”

These days, when he’s not in his office or watching on the practice fields, he’s often conjuring an image in his mind. It’s a field being sprinkled with purple and gold confetti. He sees himself — not alone, but next to Chelsea and their two boys.

This all sounds so beautifully abnormal: this man and his family, on this journey, celebrating something in the Twin Cities that would be so pleasantly unexpected.

(Top illustration: Demetrius Robinson / The Athletic; photos: Brace Hemmelgarn / Getty Images)