Editor’s note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and performance through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

Army coach Jeff Monken is just like me: He happily devours leftovers, doesn’t get nearly enough sleep and asks Alexa to play Ray Charles as background music. But if I’m being honest, that’s about the extent of my similarities with Monken, the longtime football coach at the United States Military Academy.

In his 12th season at West Point, Monken has turned the Black Knights into a stable, competitive football program. Last year, they won their first American Athletic Conference title and a school-record 12 games. Army has had six winning seasons under Monken, the most of any head coach since the legendary Earl “Red” Blaik took over in 1941.

Army is unlike most other Division I college football programs. For starters, every Army football coach since Blaik has lived in the same house on campus. Monken and his staff recruit exclusively high school players who live not in athletic dorms but in the barracks on campus. And to build at a place like West Point, Monken has to recruit players who are as interested in becoming military men as they are in running his option offense.

Although he’s coaching cadets, Monken, 58, has vowed to stay on civilian time. He jokes with his players that 3:30 p.m. is 3:30 p.m, not 1500 hours. But perhaps nothing is more precious to Monken than time. His meticulously planned, minute-to-minute schedule — both for himself and his coaches and players — reveals little leadership jewels throughout the day.

His days begin at 5:30 a.m., when he wakes up, lifts weights in the basement and helps his wife, Beth, pack lunches for their two teenage daughters, Amelia and Evangeline. Then it’s a three-minute walk from his house to his office.

7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m.: No Shop Talk

Every Tuesday at 8 a.m., Monken meets with the team chaplain, Father Matt Pawlikowski.

His conversations with Father Pawlikowski rarely revolve around football. They talk about weddings Father Pawlikowski has officiated or his travels. They touch on current events or what’s happening around campus. It’s the perfect buffer, Monken says, for him to clear his mind at the start of a day.

“It’s great for me to have a friend that I don’t have to talk shop, talk football with,” he said. “I try to find those outlets when I can.”

As you’ll see, there aren’t many.

8:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m.: The staff meeting

All Army football coaches live on campus, where there is an elementary and middle school. Monken chose 8:30 a.m. for staff meeting start times so coaches can walk their kids to school or to the bus stop, as he once did.

In total, there are 30 people in each morning meeting, from quality control assistants and members of the training staff to strength coaches and admissions representatives. A member from each department of the program provides daily updates.

Meetings start with Army’s head athletic trainer, Jacqui McCann, providing a rundown of the injury report. The up-to-date depth chart is on the wall for everyone to see. If Army plays on the road that week, Thomas Cancalosi, the director of football equipment, asks Monken and his staff if they can get him a proposed travel day roster so he can get the travel truck prepared as soon as possible.

Each day Monken has the strength staff survey some of Army’s team leaders to rate how the day’s practice was on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being the easiest. The following morning at the staff meeting, the strength coaches provide the scores so Monken can gauge how that day’s practice should be run.

“If guys are feeling worn out,” Monken said, “we start taking that pen and crossing through periods of practice to get them back to a better place physically or mentally in order to make them feel more prepared for the game that weekend.”

How, then, does he capitalize on those rare moments each day when his entire staff is together in one packed room? He’s got a head start.

“Well,” he said, “I’ve got a staff manual.”

This year’s title? “2025 staff manual.”

It’s a 13-page document that Monken started working on when he first became a head coach at Georgia Southern in 2010. Every summer, he tweaks and edits it. The manual is relevant to everyone associated with the program, not just full-time coaches.

It’s a combination of Monken’s personal mission statement for the program and West Point’s vision of its employees:

Living and leading honorably

Expectations and demands for excellence

Core values: toughness, pillars for success, importance of being disciplined and professional, building relationships, investing in people, having dignity and respect.

Lots of motivational buzzwords, but Monken believes having this guideline has helped the Black Knights win 58 percent of his games.

“We use the term servant-minded leader a lot here at West Point,” Monken said. “Part of loving someone is holding them accountable and helping them to maximize who they can be. For us, that means who we can maximize who we can be for others in the program. We all have a responsibility to each other and to the program.”

Monken’s favorite bullet point in the manual is one he ensures is done daily. Every coach and support staff member must find three different players and have “an intentional 60-second” conversation with them. The topic can be anything.

“Imagine the impact we have on our team if we’re all talking to three people a day,” he said.

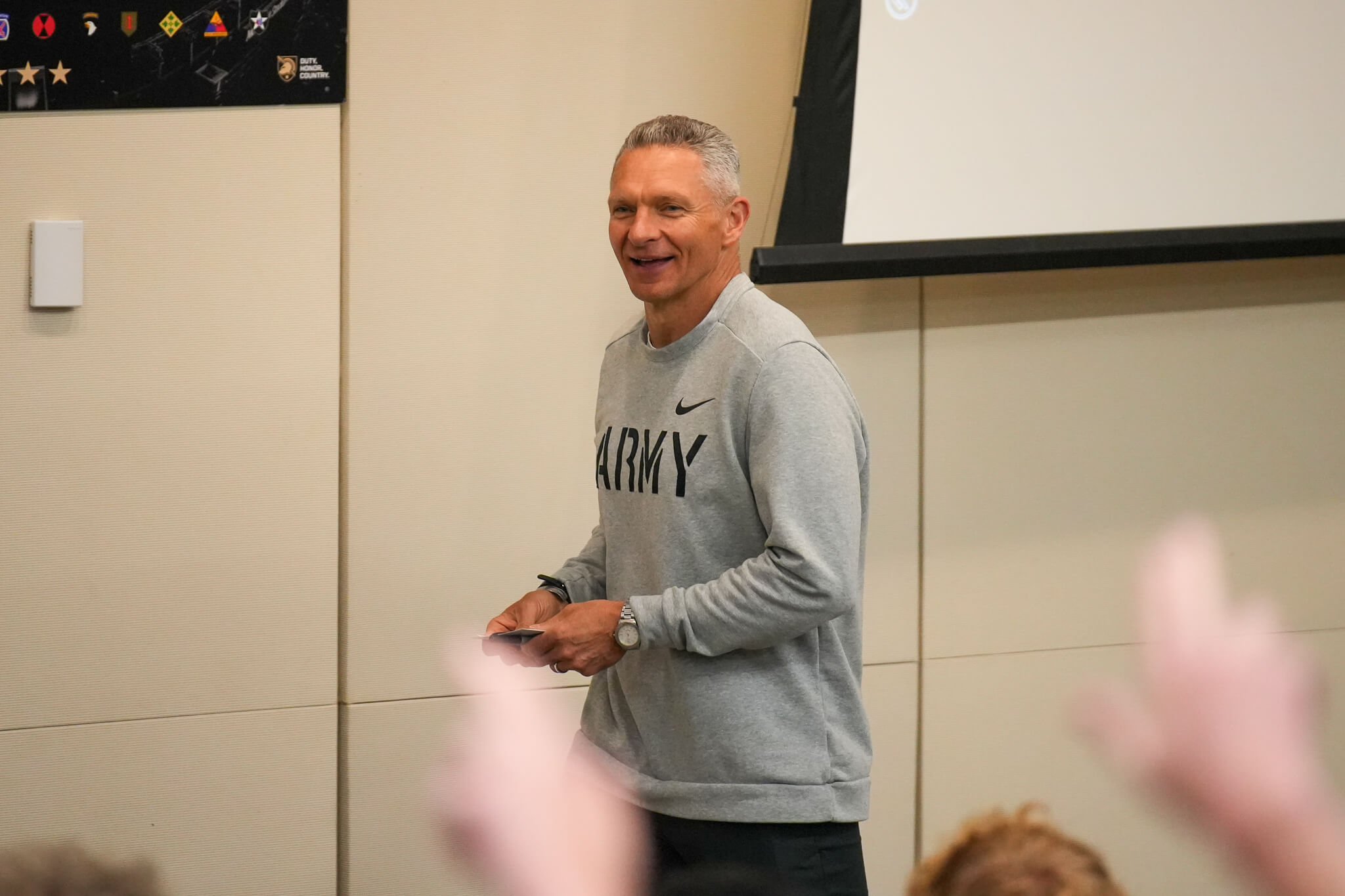

In his 12 years at Army, Monken has played in six bowl games and won a school-record 12 games last season. (Danny Wild / Imagn Images)

9:30 a.m. to 11 a.m.: Offensive staff meeting

Offensive and defensive groups split up for meetings. Monken, who came up under triple-option guru Paul Johnson at Navy and Georgia Tech, knows where his expertise is.

“Our defensive coaches are way more qualified to make adjustments than I am,” he laughed.

So he sits in with offensive coordinator Cody Worley and either goes through practice film from the previous day or watches film from the previous game. Monken will occasionally chime in, but he prefers to sit back and listen. Hearing this, I ask Monken to describe what qualities are necessary for the head of any organization to be effective.

“I think for everybody to know how they can benefit the organization,” he answered. “What is their job? Empowering them to do their job. Helping them do their job. Recognizing things they do well and encouraging them to do things better at and making corrections or helping guide them.

“Those are management and organizational skills because I can’t do it all. You’ve gotta pick people who know what they’re doing. It’s important for them to have the head coach recognize the job they’re doing, whether it be good or whether it needs improvement. To give them feedback: That’s important. To set a professional standard for everything that we do, from our promptness with meetings and the organization of those meetings, to giving them something that gives them a guideline and a plan.”

Monken said there are important jobs within the structure of the program that might not be considered high-profile to outsiders. To him, the equipment staff shuffling pieces around on the field during practice is just as important as the head coach standing by. So he’ll join in, picking up loose footballs or moving cones. If there’s a team meal one night, Monken is there to make sure there are no wayward plates or utensils left out.

“It’s important to show people there’s no job too small for the leaders of an organization,” he said. “If there’s anything that needs to be done here within the walls of our building or in our program, I try to assist and lend a hand, so that everybody in the organization sees me doing the little things that make a huge difference in the program.”

He goes back to bits of the 2025 staff manual.

“Just don’t talk about living and leading honorably,” he said. “I don’t say, ‘Follow NCAA rules.’ I am clear that no one in this program is under pressure to break any rules. In fact, I’d prefer that we follow a rule rather than win a game or sign a certain prospect. There’s an understanding of who we are as an organization and what we believe in. For them to understand who I am as a leader and what’s important to me. Because that’s what’s going to drive how they operate.”

11 a.m. to 2 p.m.: Special teams, email and maybe a FaceTime

Before returning to his office to respond to some emails, Monken meets with special teams with coordinator Sean Saturnio for an hour. Monken was a special teams coach at Navy and Georgia Tech under Johnson, so he loves to dive into the minutiae of the third and often overlooked — but not at Army — phase of the sport.

If Isabelle, Monken’s oldest daughter, who attends the University of South Carolina, is available, they might hop on FaceTime.

2 p.m. to 2:30 p.m.: Lunch — kind of

Allotting half an hour is probably too generous. Monken doesn’t take more than five or 10 minutes to finish when he finally eats for the first time each day. He walks down the coach’s break room, where he will grab either leftovers or the lunch he made at home. On this day, it’s a salad he made and a banana.

He would like to be able to have leafy greens, whole grains and lean protein every day and only water. Sometimes he bends the rules — as he shows me when he lifts a can of Coke off his desk.

“I can tell when I walk in the room if they have energy or they don’t,” Monken said of his team meetings. (Photo courtesy of Army Athletics)

2:30 p.m. to 5 p.m.: Team meeting and practice prep

When Monken was hired in December 2013, the first thing he did was have digital clocks installed throughout the football facility. In every office, in every meeting room, in the cafeteria, in the locker room, the training room, equipment room, player lounge and cafeteria.

“We’re pretty much on the clock,” he said.

It makes sense at West Point, where all admitted cadets attend the academy on a tuition-free basis. Most applicants must apply for a nomination from either a U.S. senator, U.S. representative of the Vice President of the United States. A cadet must pass the rigorous Candidate Fitness Assessment (CFA), a test designed to challenge strength, speed and endurance prior to admission. Civilian clothes are rarely worn on campus. Mandatory class attire includes gray pants, a black pelt, gray button-up shirt and a garrison cap.

There are no night classes offered at West Point, which limits the program’s ability to follow an emerging trend in college football of practicing in the morning. From when players typically start filing into the building around 2:30 until the time practice usually starts anywhere from 4 to 5 p.m., every minute is intentional for Monken.

On this day, positional meetings started at 4:03 p.m. Dress and tape in the locker room: 4:53 p.m.

When it is time for Monken to stand in front of the team, he is ready to follow his script while simultaneously ready to ditch it if needed.

“I can tell when I walk in the room if they have energy or they don’t,” he said. “And if I don’t sense it, I’ll just shift right to that. ‘We need to get our energy up. We’ve got to get going here. I can tell we’re dragging here. I don’t know what the hell happened in the barracks last night or if you guys had a bunch of tests today, but we’ve gotta get to work. And if not, we’re going to pay the price for it on Saturday.’”

During a visit to West Virginia during Rich Rodriguez’s first round as the Mountaineers’ head coach, Monken picked up on a tradition he liked: Players who had standout practices from the day before get tossed a PayDay candy bar.

5 p.m. to 8 p.m.: Practice and a tour through the training room

On this day, players need to be on the field at 5:08 p.m. for a practice that commences right at 5:13 p.m. Monken’s ideal practice is a crisp 90 minutes, but some might stretch to two hours. One of his pet peeves is seeing players taking a rep a minute and assistants having to explain things that should’ve already been relayed in positional meetings.

“I want to practice as short of a duration as possible and to get all the work done we need to get done,” Monken said.

After practice, Monken walks through the training staff room to check on injured players. That’s usually the only time they can receive treatment due to their rigorous schedules.

Monken believes the type of necessary intentionality during practice should be replicated off the field, too. In order to understand your players and get the best out of them each day, Monken said, you must be up to date on how they’re handling life as a cadet as much as a Black Knight football player. And it starts with Monken, who says he must be the example to his staffers of proving he’s invested in the people he has working for him.

“Always be visible and always be available,” he said. “That’s really important.”

“I’m not the kind of coach who puts his arm around people and sings koombaya,” he added. “I’m pushing people. I’m high demand, high motor. Accountability and discipline, but there’s love at the core of that. I do love our players, I love our coaches. It’s my responsibility to love them, and it’s our responsibility to love each other.”

8 p.m. to midnight.: Leftovers, family time, and, finally, bed

When he arrives home, leftovers await on the countertop or in the fridge. This is where the sometimes impossible task of work-life balance intersects.

The demands of the job don’t dull the pain of being absent from inflection points in each of his daughter’s lives. Monken wasn’t able to attend a single volleyball game of Isabelle’s when she was in 7th and 8th grade because they always started at 4 p.m. He’d sneak over to watch her warm-up but had to jet back to prepare for practice. Evangeline, the youngest, is on the JV cheer team. The first home game of the year was last Thursday. Monken and the Black Knights were over 500 miles away, playing East Carolina.

“When I can be there, I try to be there,” Monken said. “If I can manipulate the schedule, I’ll manipulate the schedule.”

Like the Friday before the home overtime loss to North Texas, he snuck out of the team hotel once dinner was served to go watch Amelia cheer for a bit.

“I do try to do that,” he said, “and that doesn’t make me a good dad. I want to be there for them. It’s important to me. Maybe more important to me that I’m there than it is to them. But I want to be there. We miss a lot of things.”

After trying to capitalize on that hour-long timeframe after he comes home, eats leftovers and talks to Beth and the girls, Monken takes his list of prospective recruits home with him and will either head to the front porch or down to the basement where Red Blaik once worked on odd jobs around the home. His phone is always on speaker.

“I would lose AirPods if I had them,” he jokes.

That’s his wind-down time, talking about the program he’s built in his own image, before he finally calls it a night and heads upstairs between 11 p.m. and midnight to plug in his phone and do it all again the next morning.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Dustin Satloff / Getty Images)