IOWA-WISCONSIN BORDER — Long before Highway 151 doubled in size and became a four-lane connector, buses carried the Wisconsin and Iowa football teams over a winding, two-lane paved road that led them through small towns on both sides of the Mississippi River.

Every other year, the Hawkeyes would travel 90 miles north from Iowa City to Dubuque for dinner, then cross the border to drive the remaining 90 miles to Madison. Fifteen minutes past Dubuque in Dickeyville, Wis., at a bar called the Squirrel’s Nest, patrons collected some liquid courage. They waited for the Iowa buses at a stoplight where Highways 151 and 61 meet.

As the buses approached the stoplight, cars and trucks slowly paraded through the intersection and honked at every vehicle with an Iowa license plate. Hawkeyes fans often reciprocated with a full moon in broad daylight.

“Before they bypassed everybody, there were always signs,” retired Iowa football equipment manager Greg Morris said. “‘Hawkeyes can’t do this, can’t do that.’ A lot of times coming home, there’d be something going on in one of those towns, and it’d take forever to get through.”

The Squirrel’s Nest has long since closed, but its lore reflects the role beer and football play along what could be termed the Upper Midwest’s “beer highway.”

German immigrants flocked to eastern Iowa and Wisconsin in the 1840s and 1850s, and drinking establishments sprouted all along the route from Iowa City to Madison. The confluence of available grain, crisp waterways and heavy industry amplified beer’s accessibility and influence throughout the region.

When football was introduced in the early 1890s, beer enthusiasts instantly took to the sport and straddled the Mississippi River like a roulette wheel, only with one side wearing red and the other black and gold.

As rivalries go, Iowa-Wisconsin is unique. Neither side harbors all-encompassing contempt for the other like both do for Minnesota. Wisconsin doesn’t have an annual in-state football rival like Iowa does with Iowa State.

However, Iowa-Wisconsin crushes those series when it comes to stakes. In the Big Ten’s 10 seasons of geographical divisions, either Iowa or Wisconsin advanced to the championship game seven times. Since 1998, they have combined for 20 10-win seasons and 12 top-10 finishes. Twice, the Big Ten shifted Iowa-Wisconsin off annual status, only to have administrators at both schools convince the league to move it back. The connection is too essential for the fan bases, as is the proximity between the schools.

From Iowa City, the beer highway extends 30 miles north toward Cedar Rapids, Iowa’s second-largest city, then northeast toward the state line. From the other side, the highway takes off in Madison and then bends off the main road to the charming town of New Glarus. It gathers itself along Highway 151 in both directions. Along the way, there are markers of beer’s past and vibrant present, and the role football plays in holding it all together in the 21st century.

The epicenter

Along the beer highway, Dubuque marries football and beer unlike any other city. Dubuque sits on the west side of the Mississippi River overlooking Iowa’s borders with Wisconsin and Illinois. Its magnificent bluffs and seven rolling hills define the “Driftless” area of the upper Mississippi River basin. The area was never covered during the glacial period 12,000 years ago, and the resulting topography and fall foliage help Dubuque resemble New England more than much of the Midwest.

Europeans first arrived in this area in the late 1600s, and the Meskwaki tribe granted French explorer Julien Dubuque lead mining rights in 1788, making it Iowa’s oldest city. With a mix of German and Irish ancestry, the city of 60,000 is the smallest among the United States’ 35 Catholic Archdioceses.

Dubuque offers remnants of the shot-and-a-beer tavern culture once prevalent across the Great Lakes and Upper Midwest, but it also boasts a vibrant craft beer scene. Retired sportswriter, Dubuque native and beer connoisseur Marc Morehouse knows all of these topics better than anyone.

In the 1970s, when game replays of both programs aired late Saturday nights on public television in Dubuque, Iowa and Wisconsin were equally terrible, and the city was fertile ground for whichever program got off the mat. In 1981, Hayden Fry took the Hawkeyes to the Rose Bowl, and Dubuque was forever smitten with the black and gold.

“Iowa and Wisconsin are basically joined by three bridges, but the amount of hatred that comes over these bridges is pretty amazing as far as football goes,” Morehouse said. “We’re all the same, we’re all middle ranks, and if one gets ahead of the other, that’s a little FOMO. (Former Wisconsin coach Barry Alvarez) was on ‘Entourage’; (Iowa coach Kirk Ferentz) is not going on ‘Entourage’. So, ‘Hey, you guys are a little cooler.’ You notice stuff like that.”

To Morehouse, “beer is community,” and the element that ties the fan bases together. According to Business Insider, Wisconsin ranks third and Iowa sixth in bars per capita. Beer also provides the backbone of Dubuque. The large brick building that once housed Dubuque Star Brewing, opened by the Rhomberg family in 1899, has endured 40-plus years since the brewery’s closure and still carries the company’s banner, now housing local businesses, a beer museum and a restaurant that pours two original recipes.

Dimensional Brewing Company in Dubuque contributes to the city’s beer culture, which sits at the intersection of three state lines. (Scott Dochterman / The Athletic)

A few blocks from the old Dubuque Star, Dimensional Brewing Company nods to both the current craft scene and the old days. Not necessarily a sports bar, it has a lively crowd on Saturdays when either the Hawkeyes or Badgers play. One of the co-founders, Joe Specht, considers Dimensional a throwback to Dubuque’s roots as a regional beer center.

“We all knew that Dubuque was one of the beer brewing hubs 100-plus years ago,” Specht said. “That definitely gives you added motivation to make sure that you’re doing everything the best that you can.”

Morehouse and Specht engaged in 30 minutes of beer banter, throwing around alcohol-by-volume numbers and other terms as if they were baseball stats. The explosion of award-winning breweries on the west side of the Mississippi led Specht to say, “I’d put Iowa beer up against any state’s beer.”

Morehouse shot back, “What about against Wisconsin?” Specht replied, “I would.”

Specht may be right, but in his community, some people drive east across the Dubuque-Wisconsin Bridge into Grant County strictly for a beer brewed and sold only in Wisconsin.

Off the beaten path

New Glarus, Wis., and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, share little in common — barely 2,000 people live in New Glarus, while 280,000 reside in the Cedar Rapids metro area — but they are equally compelling detours off the most direct route between Madison and Iowa City.

It’s a winding series of turns heading east to reach picturesque New Glarus, which is located about 70 miles east of Dubuque and 30 miles south of Madison. Founded as a Swiss village in the heart of German America, New Glarus found its niche with Old World charisma. However, the quaint streets and charming exteriors belie the beer behemoth that resides within the community. All along the border, beer-loving non-residents drive to gas stations and small grocery stores to buy 12-packs and cases of the beer proudly bearing the label “Only in Wisconsin.”

Not since the 1970s, with Coors in Colorado, has a beer captured the public’s imagination like New Glarus’ Spotted Cow. It ranks No. 2 behind only Miller Lite as the state’s best-selling beer. Spotted Cow makes appearances at tailgates throughout the Upper Midwest, including in Iowa City. Its popularity once led a bar in Minnesota to buy it and resell it, ultimately leading to felony charges.

In 1993, Deb and Dan Carey sank their life savings to start New Glarus Brewing Company, with Deb serving as president and Dan as master brewer.

In the mid-1990s, Deb joked about the spotted cows — officially known as Holsteins — on Wisconsin dairy farms and told her husband she wanted a beer named for them. She even drew the design on a napkin with a magic marker. The beer had a name without a flavor.

Dan concocted a farmhouse ale made with 1850s roots. With modern technology, a preferred strain of yeast and constant tinkering, it combined multiple elements into one pilsner beer — light and amber, fruity and sweet, smooth as a domestic beer but as flavorful as a craft brew. Spotted Cow has become a sensation, making up around 55 percent of New Glarus’ 236,000 barrels sold in 2024.

“It’s our gateway beer,” said Craig Shea, a hospitality team lead for New Glarus. “What are your two things that you got to try when you come to Wisconsin? Cheese curds and Spotted Cow. If you don’t try that before leaving the state, you’ve missed out.”

On a mid-July afternoon, the older New Glarus facility was packed while construction of a new $55 million facility was underway. The Spotted Cow cult following — which paved the way for the brewery’s equally passionate Moon Man IPA frenzy — provides New Glarus with visits from locals and beer fans alike.

However, that day’s crowd was a fraction of the traffic the brewery sees on Wisconsin game days, when employees sport the Badgers’ colors and mingle with opposing fans as much as with Wisconsin fans.

New Glarus beers have garnered a passionate following around (and outside of) the state of Wisconsin, the only place they can be made or sold. (Scott Dochterman / The Athletic)

The flip of the New Glarus phenomenon on the Iowa side is Cedar Rapids, which sits 30 miles north of Iowa City and 70 miles southwest of Dubuque. A community where the Rust Belt blurs into the Great Plains, Cedar Rapids is known for its smells.

On some lucky afternoons, that includes the luscious aroma of Cap’n Crunch’s Crunch Berries from the Quaker Oats cereal mill. Other days are defined by less appetizing odors from the industrial activity in the area. Both Iowa’s football team and its opponent stay in Cedar Rapids the night before home games. There’s a vocal presence of Iowa State supporters, but the overwhelming majority follow the Hawkeyes.

The City of Five Seasons became a home for Czech refugees in the early 1850s, and the city’s beer heritage includes a pair of German breweries from around that time that used underground caves to keep beer cool before the dawn of refrigeration. The businesses operated in secret during Prohibition but closed once the 18th Amendment was repealed. The caves were rediscovered in 2014, but because of their proximity to Interstate 380, Iowa’s Department of Transportation elected to fill them in rather than mark them as a historical site.

Lion Bridge Brewing Company, named for the lion statues that greet visitors crossing the Cedar River from downtown Cedar Rapids, boasts a collection of 21 beers on tap, ranging from its gold medal-winning Compensation, an English mild ale, to Bohemian Premium and Oktobot 3000, which tap into the area’s Czech and German roots. Lion Bridge also offers a corn-based Yield of Dreams, a nod to its home state.

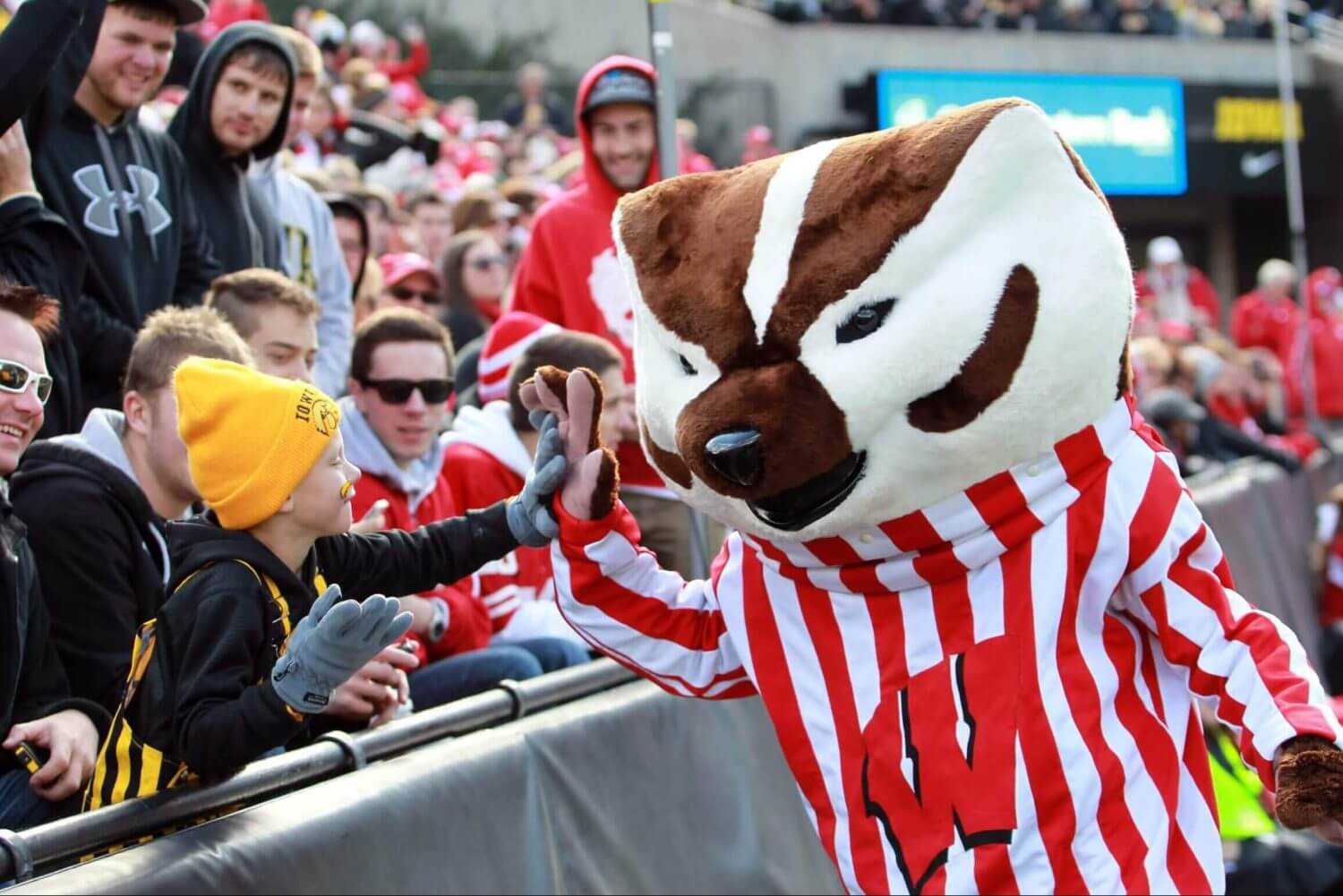

Their rivalry has often carried significant Big Ten stakes, but Wisconsin and Iowa are more alike than they are different. (Reese Strickland / Imagn Images)

Campus life

Both universities have spent time atop the Princeton Review’s party school list, Iowa ranking No. 1 or No. 2 every year from 2012 to 2015 and Wisconsin earning top honors in 2005 and 2016. And within the bar scene along State and Regent streets in Madison and inside the Ped Mall in Iowa City, the heart of college football beats with a rhythm unmatched anywhere else throughout the beer highway.

This weekend, the Badgers host the Hawkeyes in a prime-time battle, and fans of both schools are likely to fill Jordan’s Big 10 Pub, located just two blocks east of Camp Randall Stadium. It boasts Regent Street’s largest outdoor beer garden, with up to 1,500 fans filling up three different indoor rooms as well as the outdoor parking lot. In all, Jordan’s has seven functioning bars on game day.

“You can’t walk more than 20 feet without running into a bar,” said bartender Anthony Cable.

In Iowa City, about two miles from Kinnick Stadium, Big Grove Brewery has become the “it” place the night before home football games. The massive indoor bar seats up to 485 people, and the outdoor patio can accommodate 700 people on its own. For Iowa home weekends against Big Ten opponents, nearly 30 percent of the Friday night clientele wear opposing team colors. Most of the fans keep it light and engage in friendly banter rather than antagonize one another.

“It’s all friendly fire,” Big Grove bartender Amber Thoma said. “It’s all in fun.”

At Jordan’s Big 10 Pub, the layout is “so much red,” Cable said, but the atmosphere is the same.

“As long as I’ve been working here, we’ve built this culture where it doesn’t matter if you’re a rival team or different team, a different conference, we’re gonna treat you the same way we treat everyone else,” Cable said.

The road through northeast Iowa and southwest Wisconsin offers a window into the character of both states and their flagship universities’ fan bases. (Scott Dochterman / The Athletic)

The route best traveled

People who live along the beer highway are largely welcoming but emotionally reserved. They balance their skepticism with earnestness.

In football, the programs are middle-class, capable of both upward mobility and collapse. This year, Wisconsin (2-3) is struggling, while Iowa (3-2) remains undefined. The series began in 1894, and the Badgers lead 49-47-2. They play for the Heartland Trophy, appropriately, an 80-pound replica of a bull.

In the summer, lush green pastures and 6-foot cornstalks hug the highway like veins funneling blood through the region. As the calendar shifts to October, those cornstalks now sway harvest beige until they meet the combine. The fields, the pints and the football largely look the same in both Iowa and Wisconsin, and the beer soaks the palate of life along the Driftless beer highway.

“It’s like Barney from ‘The Simpsons’ and Otis from ‘Mayberry,’ ” Morehouse said. “Oh, we’re kind of the same. Let’s hang out and have a beer.”