If you ask someone what the NFL’s “premium positions” are, you will often get the following list:

Quarterback

Wide receiver

Offensive tackle

Edge rusher (or “pass rusher”, to include interior threats)

Cornerback

Does that list have too many bullets?

That conversation is worth having after the New York Jets’ recent blockbuster trade.

It’s time to reconsider whether cornerbacks have “premium” impact

If the Indianapolis Colts’ offer for Sauce Gardner is any indication, some NFL teams still view cornerbacks as premium assets. To acquire Gardner, Indy gave up two first-round picks and a 23-year-old player recently picked in the second round (wide receiver Adonai Mitchell).

It’s a comparable package to the one that star edge rusher Micah Parsons netted for the Dallas Cowboys. The Green Bay Packers sent two first-round picks and 30-year-old defensive tackle Kenny Clark to Dallas for Parsons.

This comparison implies one of two things: either the Colts massively overpaid for Gardner, or the Cowboys did not receive nearly enough for Parsons.

The truth likely lies in the middle. Either way, the values of these deals do not align, because from a salary-cap perspective, the NFL no longer views cornerbacks as one of the most valuable positions.

Based on today’s market, we are down to three premium positions (with quarterback in a class of its own): quarterback, edge rusher, and wide receiver.

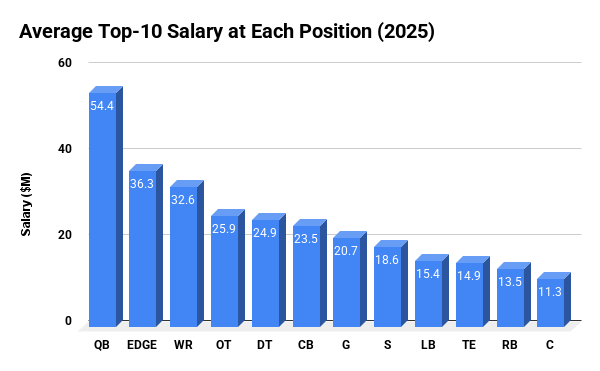

Here is a look at the average salary of the top 10 highest-paid players at each position in 2025.

Quarterback ($54.4M)

Edge rusher ($36.3M)

Wide receiver ($32.6M)

Offensive tackle ($25.9M)

Defensive tackle ($24.9M)

Cornerback ($23.5M)

Guard ($20.7M)

Safety ($18.6M)

Linebacker ($15.4M)

Tight end ($14.9M)

Running back ($13.5M)

Center ($11.3M)

The top cornerbacks are closer in average salary to the lowest-paid position, centers, than they are to edge rushers. The gap between wide receivers and cornerbacks is larger than the gap between cornerbacks and tight ends, the 10th-ranked position.

We can essentially group the positions into four tiers:

Tier 1: Quarterbacks

Tier 2: Premium (EDGE, WR)

Tier 3: Semi-premium (OT, DT, CB, G)

Tier 4: Luxury (S, LB, TE, RB, C)

Collectively, the NFL has moved past valuing cornerbacks as a premium position. It shows why the Colts’ offer for Gardner was impossible for the Jets to turn down. Indianapolis overpaid for Gardner under the outdated mindset that an elite cornerback can affect games to the same degree as an elite edge rusher like Parsons.

Dallas mishandled Parsons and should’ve got more for him; that is still true, and it’s an entirely different conversation. At the same time, even compared to the underwhelming Parsons package, the Colts took a massive risk by giving up the same package for Gardner as Dallas did for Parsons. It simply doesn’t align with modern NFL value.

Indy’s exorbitant offer for Gardner highlights the reality about cornerbacks in today’s league: They cannot impact games the way they used to.

Cornerbacks cannot take over games

What separates the three most valuable positions from the rest of the pack?

They can take over games.

The ability of a quarterback to take over a game doesn’t require a thorough explanation (although I ended up writing one anyway).

Quarterbacks handle the ball on every snap. If you have a great one, he can make things happen no matter the situation. Even if the defense generates pressure, provides excellent coverage, and makes the perfect play call, the quarterback has the power to override all of those factors. He’s the only player on the field who can do that on every play, and it’s why he makes the most money.

READ MORE: Why it’s critical for the Jets’ future that Justin Fields alters play style

If quarterbacks are the most valuable player on the field, the next-most valuable players must be the ones that are the most closely attached to his success. That brings us to wide receivers and edge rushers (or, more broadly, pass-rushing defensive linemen).

While every position on the field affects the quarterback to some degree, most of them are unable to be consistently dominant from down to down. They can’t make a game-changing impact on a play unless circumstances fall their way, whether it’s a running back needing great blocking or a cornerback needing to be targeted.

Wide receivers and pass rushers are the rare non-quarterback players who can truly take a game over and force opponents to alter their game plans around them.

A quarterback and play caller can dial up throws to a star receiver anytime they want. If the receiver is talented enough, he can overcome great defense to make a play in any situation; it’s why Garrett Wilson is the one player New York deemed untouchable at the deadline. Nothing frustrates a coach more than calling the right play, generating pressure, and covering perfectly, only for a receiver to catch a jump ball or break some tackles on his way to an explosive play.

Until the defense adjusts to take away the opponent’s best receiver, the offense can and will throw to him on every play. The only reason offenses don’t do this is because any defense worth its salt will build its game plan around preventing it; something they would never do for an offensive lineman, tight end, or running back (save for the Saquons and Henrys of the world).

Defense is mostly reactive, while offense is proactive; this is why offense is more valuable and more stable/predictive from year to year. The exceptions to this rule are the pass rushers, the most proactive players on the defense.

Unlike defensive backs and linebackers, defensive linemen don’t have to wait for the ball to come to them to affect a play. They line up the closest to the quarterback. Each rep, they have a chance to cause havoc by beating a blocker and getting into the backfield, especially on passing plays, which is where most of the value lies in today’s league.

Like wide receivers to the defense, offenses will scheme to stop a pass rusher. They don’t care too much about working around a star safety, linebacker, or cornerback, since those guys line up far away from the ball and can be easily avoided. But T.J. Watt lines up just a few yards away from their prized quarterback, so they will make sure toward the opposite edge and consistently throw extra pass-blockers on his side.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of star wide receivers and pass rushers is that their production is more talent-based and less scheme-reliant than most other positions. Whether it’s catching a 30-70 ball or getting a strip-sack off a spin move, these positions make their impact through pure ability. You cannot scheme your way into replicating what someone like Justin Jefferson or Myles Garrett can do, the same way you can scheme around the loss of a running back or a cornerback.

The Jets have seen this firsthand with the players they just traded.

#Jets‘ record without Sauce Gardner and Quinnen Williams since they were drafted:

4 games without Sauce: 3-1

11 games without Quinnen: 2-9

— Michael Nania (@Michael_Nania) November 6, 2025

Gardner netted a significantly larger trade return for the Jets than All-Pro defensive tackle Quinnen Williams. Yet, the Jets are 3-1 in games missed by Gardner, compared to 2-9 in games missed by Williams.

This isn’t a slight on Gardner’s ability. He’s as good as it gets at the cornerback position. His coverage metrics since he entered the league are in a class of their own.

It’s just the reality of the cornerback position in today’s league: They usually can’t do much to affect the play.

The rules are built upon it.

It’s simple: The NFL wants money. To earn money, they need viewers. To generate viewers, they need high-scoring games; it’s well-established that fans find high-scoring games substantially more exciting than low-scoring ones. To generate high-scoring games, they need the most explosive players on the field, the wide receivers, to have the freedom to put on a show.

The victims: Cornerbacks.

Read the rulebook for yourself.

ARTICLE 2. ILLEGAL CONTACT WITHIN FIVE YARDS

Within the five-yard zone, if the player who receives the snap remains in the pocket area with the ball, a defender may not make initial contact in the back of a receiver, nor may he maintain contact after the receiver has moved beyond a point that is even with the defender. If a defender contacts a receiver within the five-yard zone, loses contact, and then contacts him again within the five-yard zone, it is a foul for illegal contact.

ARTICLE 3. ILLEGAL CONTACT BEYOND FIVE-YARD ZONE

Beyond the five-yard zone, if the player who receives the snap remains in the pocket area with the ball, a defender cannot initiate contact with a receiver who is attempting to evade him. A defender may use his hands or arms only to defend or protect himself against impending contact caused by a receiver. If a defender contacts a receiver within the five-yard zone and maintains contact with him, he must release the receiver as they exit the five-yard zone.

Here’s the TL;DR: “Hands off our precious money-makers.”

Because of the league’s decidedly pro-receiver rules, cornerbacks have no capability of dominating games the same way that Darrelle Revis and Deion Sanders once did. They can’t follow superstar receivers around the field and play bump-and-run coverage; you’d be asking for a flood of penalties against a league of receivers who are becoming smaller and quicker to draw more and more flags in this anti-contact league.

“Island” corners are extinct. Some teams play more man coverage than others, and some corners (with Gardner being among them) are good enough to draw some designated star-erasing assignments in critical situations. But no player does this on a snap-to-snap basis anymore.

In response to the rules rendering man coverage too risky, it’s become a zone-heavy league; even the most man-heavy teams play more zone than man. Even when teams do appear to play “man,” it’s often a match coverage in which the defenders read the route concepts and pick up receivers based on when and where they break. Coverage has become a scheme-based endeavor, with each player being little more than a cog in the machine.

Not to mention, the rapid increase in athleticism at the quarterback position has increased the risk of playing man coverage. If you have your defenders turn their backs to the line of scrimmage, most starters in today’s league will scramble for a first down. That wasn’t the case 15 years ago, when the league was overrun with statues.

For most of the game, your star corner could be doing cardio in zone coverage. Since it’s too difficult to have corners shadow star receivers nowadays, offenses can easily move their star receiver to the most favorable matchup and pepper him with targets over there, while hiding their worst receiver in the star corner’s area.

Today’s corners are paid to simply do their job: Execute your coverage responsibility, play the ball when it’s in your area, and finish tackles. If you check those three boxes, you’re golden.

Gardner is elite in most of those areas, and he still has an elite impact because of it. But the rules disallow him and his peers from having the type of omnipresent impact that Micah Parsons or Myles Garrett can have.

Cornerbacks cannot take over games, and it’s reckless to value them on the trade market as if they can.

New York fleeced Indianapolis in the value game, regardless of outcome

The Jets have to nail their picks (and develop Adonai Mitchell) to make this trade worth it in the long run. That much is obvious.

Regardless of whether they maximize these assets in the future, they already won this trade from a pure value perspective. New York baited Indianapolis into giving up a premium haul for a player at a non-premium position.

If they play their cards right, this could be the trade that turns the franchise around.

As great as Gardner is, it speaks volumes that the Jets are 3-1 in games he’s missed, compared to 2-9 without Quinnen Williams. It’s more of a slight on the NFL for its anti-cornerback rules than it is on Gardner’s talent.

The assets netted by Gardner have the potential to yield a substantially greater impact on winning than Gardner did individually. Whether that happens will depend on the Jets finding ways to utilize those assets to address their issues at the three premium positions: quarterback, pass rusher, and wide receiver.

For Indianapolis, the hope is that Gardner can represent the difference between an early playoff exit and a Super Bowl run. By making this trade, the Colts have signaled their belief that they can win a championship as soon as this year, and that Gardner can fill the gap separating them from a feel-good story to a real Lombardi threat.

It’s a reasonable evaluation of their roster. Based on DVOA, the Colts’ pass defense, ranked 13th overall, is their worst unit of the big four. They are top-11 in pass offense (5th), rush offense (2nd), and rush defense (11th).

If Gardner’s ability to make a big pass breakup against Stefon Diggs or Courtland Sutton is the difference between Indianapolis making one of the most surprising Super Bowl runs in history and going home in the wild card round, this will be an excellent trade, one that would’ve been justified at any price.

That’s an exceedingly optimistic gamble, though.

Win-now teams often lose trades because they are unrealistic about their chances of competing immediately. Think about it: Many teams just made win-now trades, but a maximum of one can win the Super Bowl. The rest will be left wishing they had more assets to rebuild their team after falling short of the goal that would have justified their gamble.

This isn’t to say Gardner is a fully “win-now” move; the Colts have him locked up for the long run, and he’s only 25. He will help them compete for years to come.

However, by treating Gardner as the “missing piece” (as implied by overpaying for him), the Colts have risked shooting themselves in the foot by overestimating their own roster. Two months ago, the Colts had no plans of being here. Now, after a nine-game outlier run from Daniel Jones, they convinced themselves that paying a premium price for a non-premium player was worthwhile because it could get them over the top in 2025.

We’ll see about that.

Unless the Colts win it all this year, they will enter the 2026 offseason seeking the final pieces that can elevate them from playoff contenders to Super Bowl champions. But they will have to do it without their next two first-round picks, their 2024 second-round pick, and ample cap space allocated to Gardner.

Gardner is an elite player, but as we’ve established, corners can’t single-handedly win games. So, unless the Colts truly were a cornerback away from being the 2025 Super Bowl champions, they may live to regret dumping a treasure chest of assets for a player who can’t take over games.

Is Daniel Jones really the guy? They had better hope so, because if he turns into a pumpkin, they no longer have the assets to get someone better.

What if Michael Pittman Jr. or Alec Pierce suffers a serious injury? Well, the Colts had a high-upside second-round wide receiver developing in the background, but that security blanket is gone.

This trade can only truly work out for Indianapolis in the perfect world they’ve painted of themselves, where they’re a No. 1 seed with elite talent in every area except for pass defense, and by adding Gardner, they are now a complete juggernaut that will cruise to the Super Bowl. Otherwise, they will probably end up losing more value than they received, at least in terms of impact on generating wins.

The Jets have a chance to reap the rewards of the Colts’ sudden desperation.