Ole Miss quarterback Trinidad Chambliss on Friday petitioned a Lafayette County (Miss.) Chancery court for an injunction to force the NCAA to allow him to play a fourth “countable” season of in what would be his sixth year of college.

The case, brought by attorneys Tom Mars, William Liston III and W. Lawrence Deas, argues that Chambliss is a third-party beneficiary and that the NCAA has breached a contractual duty of good faith and fair dealing. Chambliss v. NCAA could shake up the system of waiver requests for college athletes and spawn other lawsuits.

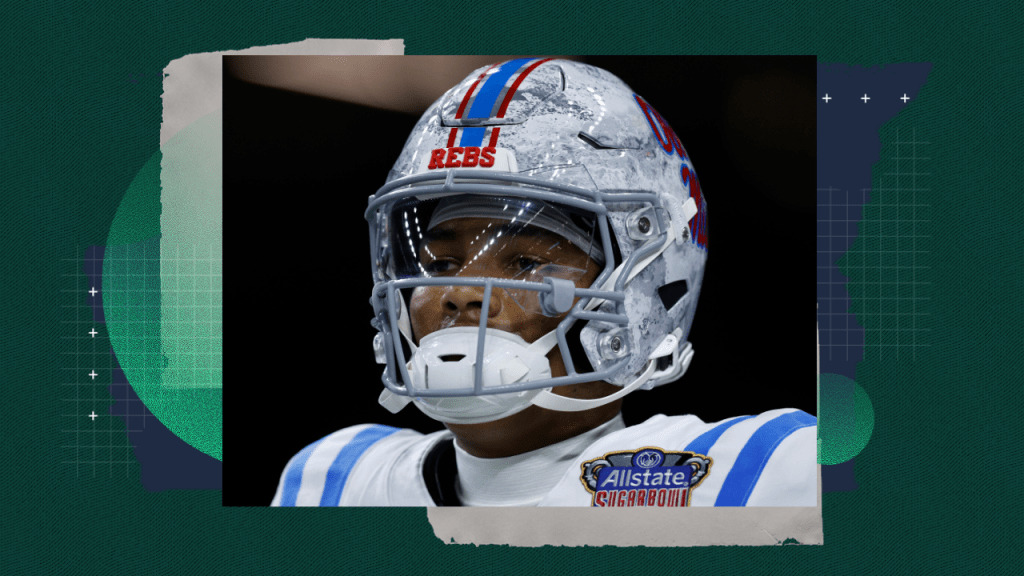

Chambliss, 23, attended Division II Ferris State from 2021 to 2024. He redshirted in 2021 and, though on the Bulldogs roster in 2022, recorded no passing or rushing statistics. Chambliss then starred for Ferris State during the 2023 and 2024 seasons, during which the Bulldogs won the Division II championship. Chambliss transferred to Ole Miss for the 2025 season, where he excelled, throwing for 22 touchdowns against three interceptions. He earned the SEC Newcomer of the Year award, the C Spire Conerly Trophy for the best college football player in Mississippi and second-team All-SEC honors.

The NCAA limits eligibility to four seasons of intercollegiate competition—including junior college and Division II competition—within a five-year period. Chambliss seeks what would be a fourth full season, with his redshirt season and 2022 season not counting, across six years.

Ole Miss filed a waiver request two months ago, citing an incapacitating illness or injury. To obtain a waiver that extends the eligibility clock, an athlete must have been denied two seasons of competition “for reasons beyond the student’s or school’s control.” The NCAA says a redshirt year “can be used only once” in this calculation.

Last week, the NCAA formally denied the request on grounds of insufficient medical documentation. It provided a verbal denial to Ole Miss a month earlier.

The NCAA says the documents provided by Ole Miss refer to a doctor’s visit in December 2022, with a physician writing that Chambliss was “doing very well” after last seeing him in August 2022. The NCAA also contends that Ferris State “indicated it had no documentation on medical treatment, injury reports or medical conditions involving the student-athlete during that time frame” and that the school instead attributed Chambliss not playing to “developmental needs and our team’s competitive circumstances.”

Ole Miss has appealed the decision to the NCAA’s Academics and Eligibility Committee, which has oversight over eligibility requirements. The committee is part of a new NCAA governance structure with student-athlete representation unveiled last August. The appeal has not yet been decided.

Mars, one of Chambliss’ attorneys, previously indicated to Sportico that unless Chambliss was deemed eligible for 2026, Chambliss would sue the NCAA. That has now happened. Chambliss demands an extension of eligibility through a motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction prohibiting the NCAA from deeming Chambliss ineligible.

Chambliss argues the NCAA is “in violation of its own bylaws and policies” by denying him a fourth season. He maintains “medical and physical incapacity prevented” him from training and developing athletically in 2021 and “debilitating medical conditions worsened and likewise prevented” him from competing in 2022.

Chambliss points out that as a student-athlete, he has “no voice or even a right to directly petition the NCAA for relief.” Instead, he must rely on his school, Ole Miss, advocating for him. Chambliss argues that he is a third-party beneficiary of the contractual relationship between the NCAA and member institutions. In law, a third-party beneficiary isn’t a party to a contract but nonetheless has a protected and enforceable legal interest in the contract being performed. Chambliss’ alleged interest is in the NCAA pledging to member institutions that it evaluates student-athlete eligibility based on “total circumstances” and well-being, and related duties of good faith and fair dealing.

Unless an injunction is granted, Chambliss says he’ll be “permanently deprived of the culmination of his stellar collegiate athletic career.” The petition—which, not unimportantly, will be reviewed by an elected judge from the county in which Ole Miss sits—also points out that Ole Miss has a stake in a player who “is essential to the success Ole Miss athletics and to the vast economic benefits which flow therefrom.”

The Chambliss situation is different from litigation brought by Vanderbilt quarterback Diego Pavia and others who challenge the compatibility of the four-seasons/five-year restriction with federal antitrust law. Their basic argument is that counting a Division II or junior college season as a season within the definition of NCAA eligibility is wrong since it’s not a Division I season. They also maintain that denying additional eligibility prevents these players from obtaining NIL, revenue share and other opportunities in the labor market for power-conference football players.

Chambliss insists the NCAA has misapplied its own rules and negligently denied him a chance to play. There was a preview of this argument on the social media platform X, where Mars recently posted a statement attributed to Ferris State head football coach Tony Annese and dated Nov. 13, 2025, in which Annese told the NCAA Academics and Membership Affairs Committee he supported Chambliss’ request.

“During the 2022 season,” Annese is quoted as writing, “Trinidad was suffering from some serious medical conditions. He was being treated for post-COVID complications that included heart palpitations and chest pains. In addition, he was suffering from chronic tonsillitis and adenoiditis that severely impacted his breathing, sleep and overall physical condition.” This statement would appear to contradict the NCAA’s assertion that Chambliss failed to provide medical documentation.

In his court petition, Chambliss says in August 2022, he was examined by Dr. Anthony Howard, an otolaryngologist in Michigan “for consultation regarding the hypertrophy of his tonsils.” This follows what is described as persistent tonsillitis and adenoiditis during Chambliss’ time at Ferris State. Howard wrote that Chambliss’ tonsils were, as described by the petition, “substantially enlarged with fleshy protrusions emanating from his tonsil tissue” and would likely cause him sleep apnea, nasal congestion and recurrent illnesses. Surgery was an option, but Chambliss didn’t want to miss up to two months in recovery.

The petition says that in 2023 and 2024 Chambliss took Claritin and Flonase “to battle his symptoms, including recurrent infections.” However, his problems led him to have surgery in late 2024 removing his bilateral tonsils and adenoids.

Chambliss’ petition says this information, along with a letter from Coach Annese and former Ferris State assistant AD for sports medicine Brett Knight, all verify his “incapacity in 2022.” Knight wrote that in 2022, Chambliss’ health conditions “impeded” his “ability to consistently engage in athletic activity including weight training, conditioning, and football practice.” Chambliss accuses the NCAA of “acting in bad faith” by allegedly ignoring those statements.

Chambliss is also highly critical of the appeal process. He claims that during a Dec. 8, 2025, call with Taylor Hall, Ole Miss senior AD for compliance, an NCAA staff member “admitted that Dr. Howard’s letter sufficiently demonstrates” his incapacity in 2022 “but nevertheless the NCAA staff member inexplicably denied the waiver request due to an alleged lack of contemporaneous medical documentation.”

The petition thus focuses, in a critical light, on how the NCAA has applied its waiver rule and the accompanying appeals process. Chambliss claims a breach of contractual duty of good faith and fair dealing, arguing he is a third-party beneficiary of the contractual relationship between the NCAA and member institutions.

To obtain an injunction, Chambliss must convince a judge that he would suffer irreparable harm if he’s denied a chance to play at Ole Miss.

In law, irreparable harm is a harm that is difficult or impossible to quantify and thus money damages can’t fix it. Chambliss asserts that missing the chance to play in Ole Miss games that will never be replayed, and the opportunity to help the Rebels win and cultivate his skills and talents, are irreparable harms. Also, while lost revenue share and NIL opportunities might be calculable, Chambliss would argue their values are tied to his performance and fame, which are harder to measure and connected to whether he can play for the Rebels.

Further, Chambliss warns he will be “forced” to hire an agent and “enter the 2026 NFL draft.” That would allegedly cause him to “sustain monetary losses in the millions of dollars, measured by the difference” between the value of his NIL and what he would expect to earn in his first year in the NFL.

While Chambliss only seeks an injunction in this petition, he could later expand his case to raise other claims and seek monetary damages. To that point, potential damages for Chambliss could rise into the millions of dollars. He is expected to earn several million dollars in revenue share and NIL earnings in 2026 should he be eligible. Alternatively, should he enter the 2026 NFL Draft, some draft experts forecast Chambliss could be a second- or third-round pick. If that projection proved accurate, he’d likely sign a four-year contract in the ballpark of $6 million to $12 million depending on where he’s selected. It stands to reason that Chambliss could earn more in 2026 at Ole Miss than in the NFL.

Among claims that Chambliss might later add are negligence and tortious interference with Chambliss’ potential contractual relationship with Ole Miss to obtain a revenue share deal and NIL deals with third parties. In a tortious interference claim, Chambliss would depict the NCAA as wrongfully disrupting his business relationship with Ole Miss and businesses.

Chambliss’ lawsuit could also add antitrust claims. Chambliss might contend the NCAA and its member schools and conferences—which, as competing businesses, can run afoul of antitrust law by restraining how they economically compete for athletes—have joined hands through rulemaking to erect a process that denies experienced NCAA players a chance to gain from the marketplace. That argument is central to Pavia’s lawsuit, which contends that NCAA member schools prefer younger, less-known 17- or 18-year-old players to seasoned, more prominent athletes, since the latter can command more in revenue share.

The NCAA is armed with several defenses.

For starters, the NCAA will insist it has fairly and reliably applied its rules. The association asserts it has consistently required medical documentation for approval of waivers. Specifically, the NCAA has received 25 requests for clock extensions based on allegedly incapacitating injury, with nine of them involving football players. It has approved 15 of them (six in football) and says in each approval the waiver application included “medical documentation from the time of the injury,” whereas the rejected applications did not.

The NCAA could also try to blunt Annese’s email saying Chambliss missed time in 2022 due to COVID-19 and related issues. The NCAA might assert that a coach writing an email about player health does not count as medical documentation and that, instead, a physician or other health care provider needs to provide subject matter corroboration. On the other hand, that type of defense would not appear to address written statements from Dr. Howard or Knight.

The NCAA would also likely maintain that Chambliss can’t show irreparable harm. The association would insist that lost revenue share and NIL opportunities are potential monetary harms and thus not irreparable, and that Chambliss has long known how NCAA eligibility works.

The risk for the NCAA is not only that Chambliss succeeds, but that other athletes whose waiver requests have been denied since last August could feel emboldened to sue in state courts across the country.

One lawsuit begetting another has long been a legal danger for the NCAA, whether it’s Ed O’Bannon’s historic case over NIL rights that spawned a sea change and state NIL statutes, or more recently Pavia’s case that has led to dozens of Pavia-like lawsuits. It would not be surprising to see the NCAA find a way to deem Chambliss eligible as a strategy to avert more litigation involving waiver denials.