ASHBURN, Va. — Dan Quinn told himself that in his second go-round as a head coach, he wouldn’t repeat some of his mistakes of the past. He wanted to keep his focus on the full team as more of a managerial head coach instead of a play-calling one. He wanted to delegate and a staff capable of filling the voids. He wanted a front office and ownership that shared his vision and expectations. And he didn’t want talented assistants to depart for bigger opportunities elsewhere, much like Matt LaFleur and Mike McDaniel did after two years of learning under him in Atlanta.

But even as NFL head coaches and play callers seem to get younger, even as teams seem more willing to give that first-time play caller a chance, and even as more players are turning to coaching soon after retiring, Quinn is taking a rare step. He’s putting his faith — and possibly his head-coaching career — in the hands of not one but two first-year NFL coordinators and play callers, David Blough and Daronte Jones. And Quinn isn’t doing this in his first season with the Commanders; he’s doing it in Year 3, after a dreadful 2025 season that undoubtedly warmed his seat. How does a head coach know when an unproven assistant is ready for that challenge?

“You’re never ready for it until you do it,” said Tony Dungy, the Hall of Fame coach and current NBC analyst. “I had been an assistant coach for 15 years, and I thought I was ready to be a head coach, and then things come up that you have to work your way through. So they’re not going to be perfect right off the bat. But if a guy is prepared in the way he does it, he’s good about his building blocks and his fundamentals, you feel good about it.”

So what is Quinn hoping for from Blough, a former backup quarterback with minimal coaching experience, and Jones, a longtime defensive coach who has only called plays at the collegiate level?

In short, he is trying to recapture a bit of the old while seeking something brand new.

“I thought it was time for change, a new vision of how we’d want to go about it,” Quinn said. “So that’s what we did.”

Quinn has repeatedly used two descriptions when asked over the last couple of months what he wants from his coordinators. The first is collaboration. He wants his coaches to use the resources of the collective, since many of Washington’s assistants come from different systems, have different ideas and use different methods of coaching. And the second is teaching. Since arriving in Washington, Quinn has stressed the development of his players and coaches.

He’s sought coaches who have a history of adapting to their players and who teach in ways that help players learn.

With Blough, the evidence was in front of Quinn for two full seasons. Quarterback Jayden Daniels developed a strong rapport with the 30-year-old Blough during his tenure as Washington’s assistant quarterbacks coach. The two would playfully compete in games of “pig” (the football version of “horse”) before practice but then have serious conversations about the offense, about reading defenses and more.

Blough’s office in Ashburn is close to Quinn’s, and the two regularly talk through ideas. Quinn learned early that Blough had the potential to be a good coach, so when other teams requested to interview him last year for possible promotions, the Commanders blocked them.

And Blough has already had chances to show what he can do. In a Week 6 loss to the Baltimore Ravens in 2024, the Commanders ran a flea-flicker running back screen play that Blough installed. It was a trick play designed by Jeff Brohm, Blough’s former coach at Purdue. Later that season, another play Blough installed — he ran it often during his playing days with the Detroit Lions — led to Jamison Crowder’s game-winning touchdown catch with 10 seconds left against the Philadelphia Eagles. It was Philadelphia’s last loss on the way to its Super Bowl 59 title.

“I think every step along the way I’ve gotten to learn something, and as we go forward, our staff, our collective staff, 12 or 13 coaches, we get to kind of build it up from the studs around what Jayden and Terry (McLaurin) and Laremy (Tunsil) and all these guys do really well,” Blough said. “Pulling from all these different experiences, new coaches coming in who have backed up Tom Brady and Aaron Rodgers, and coaches who have been around Drew Brees and developed young quarterbacks, being able to pull from the collective so that we can all collaborate together and make this the best possible thing is what’s really stimulating right now.”

With Jones, 47, the evidence was built over his 25-plus years of coaching at the high school, Division II, FCS, FBS and NFL levels. He was most recently the defensive backs coach and defensive pass game coordinator for the Minnesota Vikings, serving as coordinator Brian Flores’ right-hand man while helping to develop the likes of cornerback Byron Murphy and young safeties Camryn Bynum and Josh Metellus.

Veteran safety Harrison Smith was among Jones’ most ardent supporters, praising him for his clear communication and his ability to teach players without overwhelming them.

“Those are the types of things from a leadership standpoint that you want to hear about developing players, making an impact, finding ways to teach it where it can be clear and concise and high standards and accountability,” Quinn said Tuesday. “And when you hear players talk that way about their position coach, that’s a big deal.”

There’s no guidebook to know when a guy is ready to be an NFL play caller. There’s no way to know whether he’ll even be good at it.

Jason Garrett, the former Dallas Cowboys coach who is now an analyst for NBC, said his first time calling plays was a whirlwind.

“Everything was happening a thousand miles an hour,” he said. “I think the most important thing, the best advice I got that I listened to, was to trust your instincts. You work hard to put your plan together, you work to call your first 15 plays, then once you get going in the game, trust what you see, trust your preparation, trust your gut and your instincts and try to put your guys in positions where they can be successful.”

For Blough, his coaching instincts have been developing for more than half of his life, dating to when he was a teenage quarterback in seven-on-seven football in Texas.

“I probably got to play in 150 games from my sophomore year to senior year,” he recalled. “They were like, ‘You just call the plays.’ As the quarterback on the field, it’s like, ‘OK, well, I know this works,’ and you get to create it. I had to create the wristbands for the whole offense. Now, I was throwing the ball too, but I was calling the plays for myself.”

When Blough played in high school, he thought he wanted to be a high school coach. When he played in college, he dreamed of one day becoming a college coach. And when he made it to the NFL, he hoped to follow his playing career with one on the NFL sidelines.

Blough, a Carrollton, Texas, native who was ranked by Rivals as the 19th-best quarterback in the class of 2014, showed some early signs of a coach-in-the-making.

“Without a doubt,” former Creekview High coach Jay Cline said. “I mean, he would give a lot of suggestions to our offensive coordinator, and they would talk a lot of football. You could just see that he had a mind that was made to be a coach. And someday, I really believe this, I really think he’ll be a head coach, whether it’s in college or the NFL. He’s definitely got that makeup about him.”

The same was clear to Brohm, who coached Blough in his final two seasons at Purdue.

“He was a really good quarterback,” Brohm said. “He’s a good leader. He was tough. You could see right away if the plan wasn’t going to work out the way he wanted at the next level, he probably could be a coach just because he was a great student of the game and just a really good person to go along with it.”

Former Purdue coach Jeff Brohm considered quarterback David Blough a great student of the game. (Steven Branscombe / Getty Images)

But Blough and Jones will no doubt face challenges in their first season with the headset. Quinn hopes having more opportunities for them to call plays in practice will lead to smooth transitions, but nothing can replicate the rhythm and pressure that comes with calling a game.

Even the best have faced it.

“I think, as with anything, we all have our strengths and our weaknesses, and you try to accentuate your strengths and at the same time surround yourself with people who will help you with your weaknesses,” said Ben Johnson, Blough’s offensive coordinator in Detroit who is now the head coach of the Chicago Bears. “He knows what those are, and I’m sure he’s doing the best he can to make sure he puts himself in a good spot. He’s a good person. I think that’s where it starts with him. And I think that’s going to resonate with everybody he’s around.”

Jones served as LSU’s defensive coordinator in 2021, when he oversaw a large defensive coaching staff and helped his unit improve significantly by season’s end. College coaching doesn’t always translate to the NFL, but the competition and stakes of the SEC come awfully close. And, as with Blough, his experiences have shaped his vision for Washington.

Blough has his convictions and non-negotiables, which were validated by years of playing and observing. Having the quarterback play under center is one of them.

“It opens up different play actions and keepers and getting (Daniels) on the perimeter in different ways,” he said this week. “I think there’s a level of communication that happens under center. I think there’s just, there’s different ways to go about things, and it’s something that I’m convicted about, with his skill set, his fundamentals, the things that we absolutely loved about him when he first got here still ring true.”

Of the 10 teams that played under center the most last season, eight went to the playoffs, including the Super Bowl champion Seattle Seahawks and the AFC champion New England Patriots.

The Commanders had the lowest under-center percentage of any team, at 13.1 percent — up from 8.8 percent in 2024, when Daniels started all 17 games.

Blough’s belief about creating “balance” in the offense — be it run vs. pass, under center vs. shotgun and beyond — shouldn’t surprise. He, like Jones, is a product of his experience. And their experiences have spanned multiple schemes and coaches.

In 2023, when Blough was a practice squad quarterback for the Lions and Johnson was their offensive coordinator, the team played under center for 44.8 percent of its offensive snaps, the second-highest rate in the league. In 2022, when he was on the Minnesota Vikings’ practice squad and observed coach/play caller Kevin O’Connell, Minnesota was under center for 46.9 percent of its snaps, the fourth-highest rate that season.

With Johnson, Blough got a close look at a balanced offense that created plenty of explosive plays. With O’Connell, he learned more about condensed split formations. And with Kliff Kingsbury the last two years in Washington, Blough was schooled on using tempo to exploit defenses.

Jones’ coaching philosophy was created similarly, as he’s learned from previous coaching stops and coordinators, including Vance Joseph, Mike Zimmer and Brian Flores. Blending the lessons learned from each place has helped shape his vision in Washington.

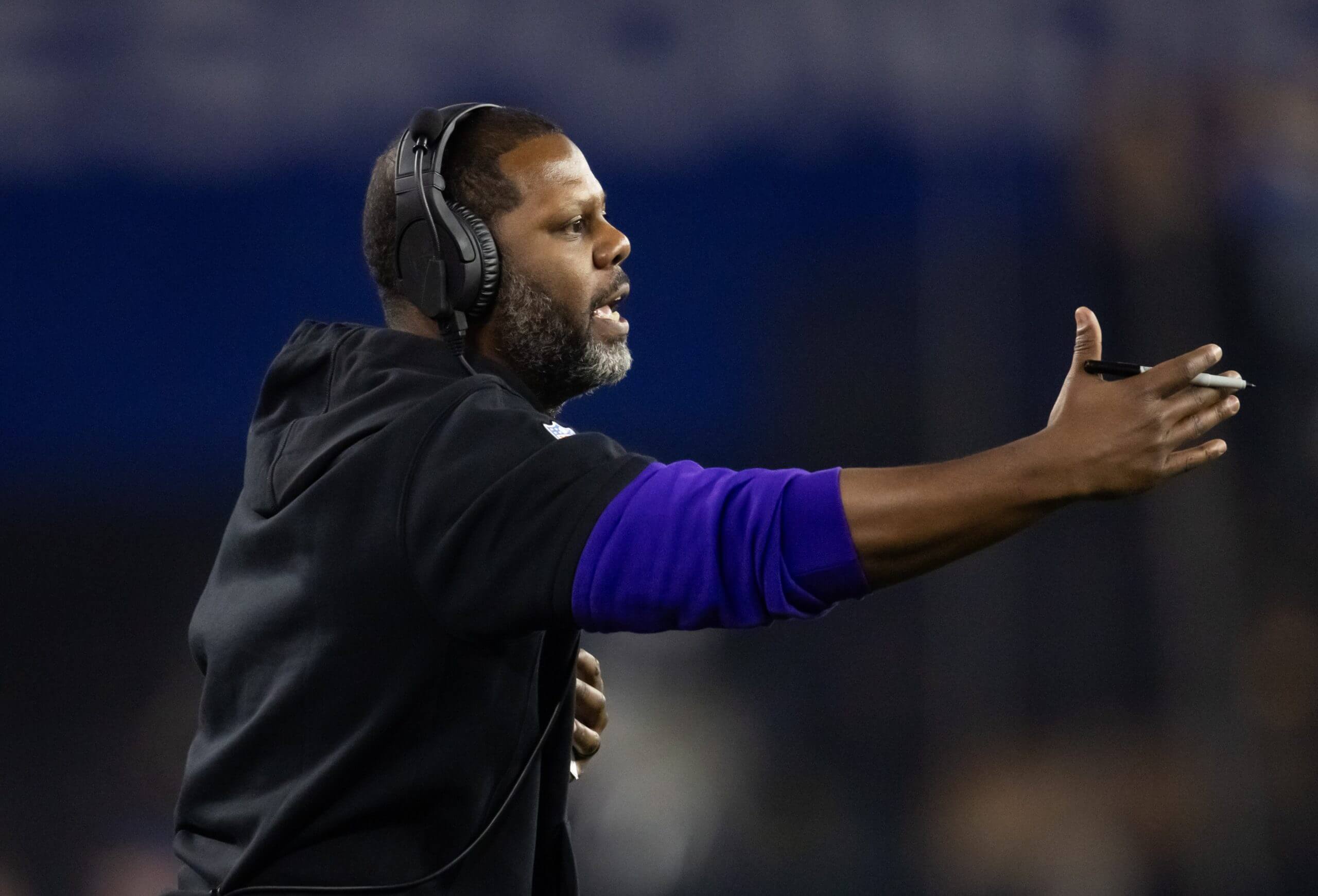

Daronte Jones earned praise from key members of the Minnesota Vikings defense. (Mark J. Rebilas / Imagn Images)

“You naturally want to be moldable because I’ve been around so many different schemes; I think that’s an advantage of mine,” Jones said. He added, “I’ve been able to implement various things from each scheme that I like and I want to pull from. So, whether it’s the Zimmer scheme, ‘Hey, I like this on third down, I like the mug looks there.’ Or if it’s Flores and the versatility, and how we can use one person in multiple ways based off of their strengths. That’s what you want to pull from.”

Blough and Quinn said the offense will essentially be built around Daniels, to emphasize what he does best while also supporting him in other areas.

On defense, Quinn stressed that the system will be Jones’ and not his own.

“Ultimately, we’re putting in a new system, and it’s going to start with his vision, with his terminology, the wording that we use, the communication,” Quinn said. “And that’s how it has to be. I think it’s difficult for someone else to come in and think like someone else.”

And Quinn said he doesn’t want to retain many of the things that failed last season during the Commanders’ 5-12 campaign. Which is partly why he is willing to bet on these two new voices, even if they both will be coordinators for the first time.

“I want to recapture that energy of that swagger of how we want to play, the style, the attitude of it,” he said. “And I’m certain we can do that. You’ve heard me also say ‘building a championship program’ this season — I’m taking the lessons, I’m moving them forward, but it’s also staying there. I’m not carrying over the things that sucked and weren’t part of how we want to do business.”