Recent CBC radio documentary reminds reporter Bob Bruton of getting his own mask delivered from Quebec, arriving by train ‘in simpler times’

The name Jacques Plante always conjures memories of my teenage years in a little near-northern Ontario town.

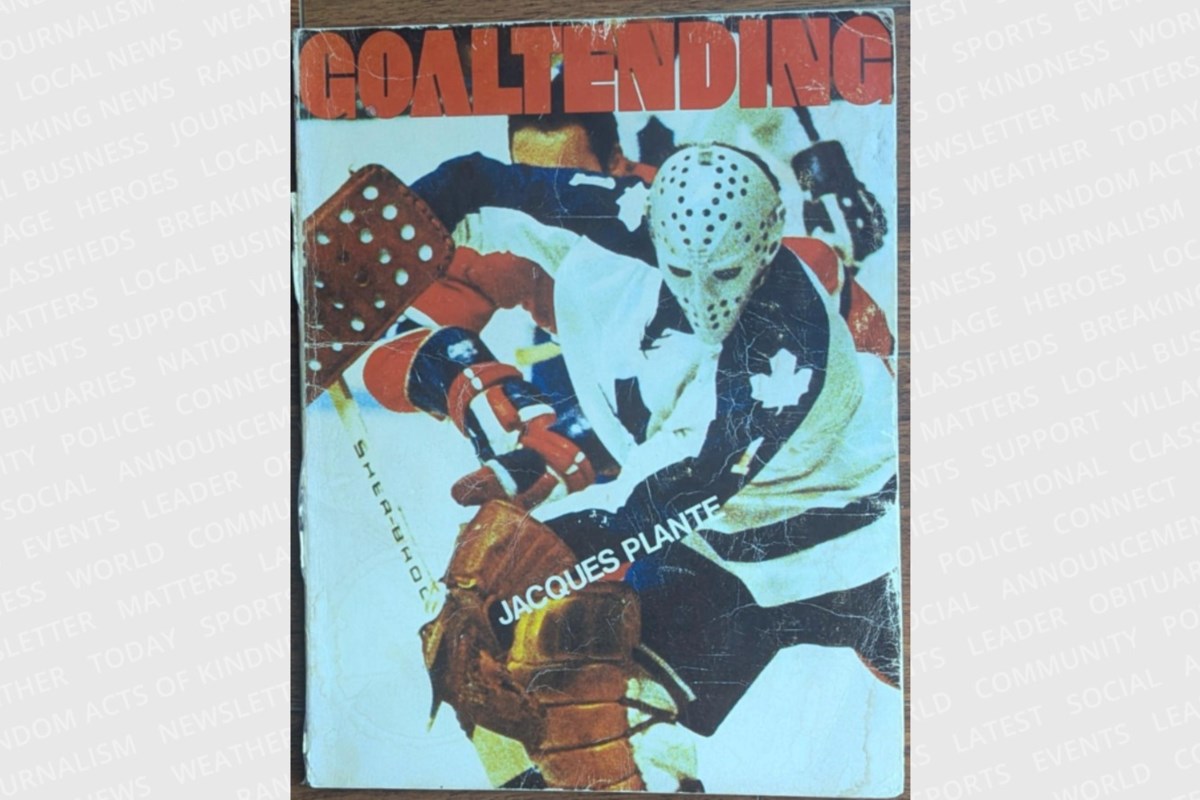

Not necessarily Plante the stellar National Hockey League goaltender of yesteryear, but Plante the pioneer of not only how goalies played, but of how they protected themselves from hard-rubber pucks.

A recent CBC radio documentary reminded me that it was Plante who first wore a fibreglass face mask while starring for Montreal Canadiens.

He was also the first NHL goalie to leave his crease regularly to play the puck, stopping it behind his net for a defenceman, or intercepting shoot-ins, disrupting forecheckers, making like a third defenceman.

But it was the mask angle which caught my interest.

In my younger years, I actually had an authentic Jacques Plante mask, as my brother pointed out after listening to the same CBC broadcast.

Plante played not only for the Habs, but New York Rangers, St. Louis Blues, Toronto Maple Leafs and Boston Bruins during his long NHL career. (Google him to get all of his Hockey Hall of Fame statistics.)

It was with Toronto I first noticed him because, well, the Leafs were always on TV and I could watch Plante play.

This was before goalies made most of their saves by being big and going down in the butterfly stance on every shot.

Somehow, some way, I noticed not only Plante’s mask but that he had a company which manufactured the masks.

So I wrote Plante and his operation a letter, asking how I could get one.

Yes, simpler times than ordering online.

My letter was answered with instructions on how to measure my head, to get the right size, and I was asked to pay by cheque — a $75 cost, if I remember correctly.

The mask had to come from Magog, Que.

A few weeks later, someone at the train station called to say there was a package for me.

My dad and I drove to the station (we could have just walked, small town) to pick up what had to be my mask.

The box it arrived in was battered, scuffed, more round than square. I wondered if my mask wasn’t broken before I even had a chance to wear it.

But the mask was fine, a good sign that it would protect my noggin.

As my brother pointed out, it also had adhesive strips of padding for a better fit.

I wore that mask for only a few seasons, took many a puck in the head and never got hurt.

I only stopped wearing it when it was outlawed by minor hockey officials, who I suspected were on the take from a large sports equipment company — although at least one NHL goalie suffered an eye injury while wearing a Plante mask.

So I put my Jacques Plante mask away, eventually selling it to a friend who played in a recreational league where it was allowed.

As my brother also pointed out, that was a mistake. I should have kept the Plante mask, as a keepsake if nothing else.

Plante began wearing a mask in 1959 because he was tired of getting pucks in the face, and eventually all goalies wore a version of his mask, which evolved into the hybrid cage/fibreglass version which all goalies wear now.

I’d like to think that every kid who ordered a Plante mask from Magog, Que., is part of that story, part of the evolution of the goalie mask.

Plante died in 1986, but he is still remembered as a pioneer in Canada’s national sport.

Bob Bruton covers city hall for BarrieToday. Council doesn’t meet much in the summer, so this is as good a time as any to write about hockey.